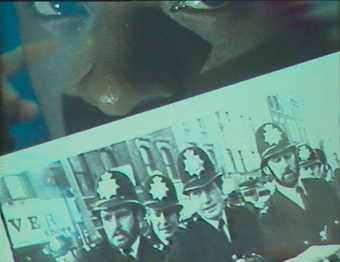

Isaac Julien (born, London, 1960) constantly pushes the boundaries of filmmaking as an art form. His works tell important stories, prioritising aesthetics, poetry, movement and music as modes of communication. Social justice has been a consistent focus of his films, which explore the medium’s potential to collapse and expand traditional conceptions of history, space and time.

Over the past 40 years, Julien has critically interrogated the beauty, pain and contradictions of the world, while inviting new ways of seeing. This exhibition is the largest display of Julien’s work to date, reflecting how his radical approach has developed from the 1980s to the present day. You will encounter films he made as part of Sankofa Film and Video Collective (1982–1992), as well as large-scale, multi-screen installations. Julien says, ‘This gradual increase in scale – from one screen to two, to three, to five, and so on – has always been in service to ideas and theories: film as sculpture, film and architecture, the dissonance between images, movement, and the mobile spectator.’

What Freedom Is To Me presents a selection of Julien’s expansive career. Places, events, and historical moments recur throughout Julien’s films: from Notting Hill Carnival, to 1920s Harlem and abolition movements.

You are invited to choose your own route through the exhibition as a ‘mobile spectator’, encountering works at your own pace, in an order of your choosing. Moving through the multi-screen installations, you will experience different perspectives, and make connections of your own with Julien’s films.

'Whenever I make a work, I’m making an interventioninto the museum and the gallery, an intervention with the moving image. Radically and aesthetically, I want to aim for an experience that can offer a novel way to see moving images, in its choice of subject, in how its displayed, in how it’s been shot … in every aspect. Since I entered the art world, that’s what it’s been all about'

Isaac Julien

‘I’ll tell you what freedom is to me. No fear.'

Nina Simone