Install image: Isaac Julien What Freedom is to me - Homage 2022 © Isaac Julien. Courtesy the artist and Victoria Miro

If you’ve explored a modern art gallery, it’s likely that you have come across some video. Unlike film, which you go to see at a certain time, video usually runs on loop. You can enter the space at any time and watch the footage from any point. As you’re thrown into the alternate world the artist presents, it can be hard to not be a little overwhelmed. It’s likely that the video you’re watching has little or no narrative. The people around might be nodding their heads and whispering intelligent remarks about the lighting and sound design. So often, we either leave the space all together or stare blankly at the screen. We’ll mimic those around us, watching with vague interest and then leave the space telling friends how the entire piece was a metaphor for the human condition. Or we may just say how it was a waste of time. If instead we take a moment to be lost in what the artist is showing us, how can we go about enjoying what we are watching?

Here are some helpful tips on how to get the most out of watching video in a gallery.

1. Forget everyone else

Juan Downey

Video Trans Americas

(1976)

Lent by the American Fund for the Tate Gallery, courtesy of the Latin American Acquisitions Committee 2010

Sometimes, collective viewing can be exciting. It’s thrilling to go to the cinema and hear people laugh or gasp at the same moments as you. However in a gallery, it can be best to block out all the noise and focus on your relationship to the artwork. There’s no need to feel the pressure to say something intelligent and original about what you’re watching. If it’s confusing, that’s just as valid as any other feeling you may have about the work. Perhaps, the artist intended for you to feel confused. Interrogate and question why you feel how you do? What has confused you? What has made you feel unnerved or joyful or emotional? By doing this, we often can come to a much richer understanding of our own connection to the artwork, rather than being concerned about what we are missing.

2. Observe carefully

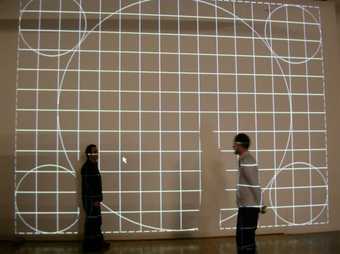

Video often gives artists an opportunity to experiment with new and innovative techniques in filming. This is often exciting to watch and can play with your perceptions of what you expect to see and what you actually can see. Before you try and understand why an artist made these decisions, focus on how they have manipulated the frame using various techniques. Where has the camera been placed? How does the camera move - is it always moving or static? What can you hear? What colours are prominent? Bruce Nauman transforms the colour of his shots in Mapping the Studio II with colour shift, flip, flop & flip/flop (Fat Chance John Cage). The seven screens constantly change colour, whilst flipping the image from left to right and from top to bottom.

The best starting point for watching video is to ask yourself how would you see this in real life? How is it different to what the artist is showing you on screen? The way an artist chooses to frame what they show is their artistic expression. Andy Warhol filmed some works in a single take, almost as if to make the experience as life-like as possible. His film Empire was shot in one night, in a single continuous take with a static camera looking out at New York’s Empire State Building from a fortieth-floor office in the Time-Life building. According to his assistant Gerard Malanga, Warhol ‘barely touched the camera during the whole time it was being made. He wanted the machine to make the art for him.’ Being able to spot those key decisions will give you a better idea of why their piece is considered art.

3. Step in and out when you like

Douglas Gordon

Play Dead; Real Time (this way, that way, the other way)

(2003)

ARTIST ROOMS

Tate and National Galleries of Scotland. Lent by Artist Rooms Foundation 2012

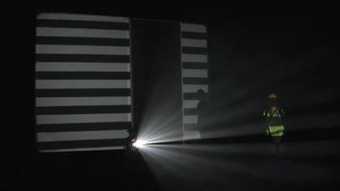

When you enter the viewing space, it can be overwhelming to start watching something that you missed the beginning of. However, it’s important to distinguish video from watching a film. While you wouldn’t start a film halfway through its run, video is played on loop, because it is designed for you to experience it at different moments. Allow yourself to be absorbed by what’s happening in the space when you step in. Video is often immersive and experiential. The narrative, if there is one, is often secondary - so don’t feel like you need to catch up on anything.

Christian Marclay The Clock 2010. Single channel video, duration: 24 hours Photographer: White Cube (Ben Westoby)

That also means you don’t have to wait until the end before you leave. Christian Marclay’s The Clock runs for twenty-four hours. Waiting until the end is not always practical. On the other hand, there are some artworks you may want to watch multiple times or return to at a later point. There’s no socially acceptable amount of time for you to stay and if you’re not enjoying it doesn’t mean you’re missing something and are not clever enough. It could be helpful though to ask why you’re not enjoying it and ask yourself what you think the artist intended their audience to feel. Each artwork is different and if you don’t respond well to one video, it doesn’t mean that another cannot inspire and resonate with you.

4. Position yourself at different places in the room

Bill Viola

Catherine’s Room

(2001)

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

Sir Steve McQueen

Caribs’ Leap/Western Deep

(2002)

Tate

© Steve McQueen. Courtesy the artist, Thomas Dane Gallery and Marian Goodman Gallery

It’s important to remember that galleries are not cinemas. Often galleries will show video with limited or no seating. Don’t feel forced to try and find a spot in the space where you can watch the film face on. Try looking at it from different angles. Try standing and sitting. Do whatever feels comfortable. Often artists, like Steve McQueen, are thinking about the environments in which their art is shown. They think about the space, as much as they think about what is on screen, in order to create a particular experience for the viewer. In Carribs’ Leap / Western Deep, McQueen shows two videos together in the same space across three different screens. The size of the screens are different and they are placed at different points in the space. Each has their own unique running time, but the two videos ultimately compliment each other and create an experience carefully constructed by McQueen.

Some video may be shown on multiple screens. Bill Viola is known for using multiple screens in his practice. In Catherine’s Room, he uses five screens that show different times of the day. You don’t need to be in a position to see everything at once and often it can be impossible to have an eye on every screen. Finding a fixed position may limit your enjoyment. Be mobile and explore the space. Often in a cinema, you become passive. In the gallery, you become aware of your presence as you move and think about the actual act of looking. Just try not to block people’s views as you go!

5. Be honest

Sanja Ivekovic

Make-up - Make-down

(1978)

Tate

Douglas Gordon

Looking Down With His Black, Black, Ee

(2008)

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

Video can challenge you. Once you have accepted that the viewing experience may not be easy, it’s likely you’ll be able to gain much more from the artwork. Your experience may be positive, negative or anything in between. If you wish to share your thoughts with others, be honest about how you found it. Each and every opinion is important. There might be film buffs around you who talk about the cinematography and editing. Learn from them, but do not be intimidated by their knowledge. It is entirely justified to talk about art in the terms that you understand and without using jargon.

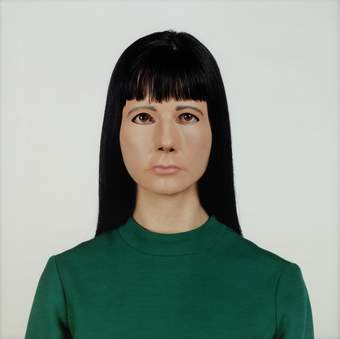

Sometimes, you may also wish to reflect on what you have seen. Time can help you process what you’ve seen and you may feel differently about something the day after you’ve seen it. In Sanja Ivekovic’s Make-up - Make-down, she records a woman applying lipstick. However, the frame cuts out the figure’s face. Ivekovic’s film critiques the way women are hyper-sexualised as glamorous. Not seeing the person applying lipstick to their face desexualises the act. Perhaps, the intention behind Ivekovic’s artwork cannot be fully realised until one actively observes and compares the way a woman applies lipstick in other media. Like with any artwork, our experience does not end when we turn away from it. If you feel lost by what you have seen, take some time. Be authentic to your own viewing experience and you’ll likely come away with a deeper understanding than you thought you would.