Known as a group who 'lived in squares … and loved in triangles’, the Bloomsbury Group were rule breakers. Playwright and critic, Bonnie Greer travels London exploring the lives of these twentieth century artists, including Duncan Grant, Vanessa Bell and Virginia Woolf.

Hear about their relationships with one another, their influence on interior design and their liberal attitudes towards sexuality.

Want to listen to more of our podcasts? Subscribe on Acast, Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts or Spotify.

[music]

Bonnie Greer: I'm Bonnie Greer, and you're listening to Walks of Art. In this episode, we're going to be exploring the art of Bloomsbury. Is really to be a Bloomsbury local, there are so many nationalities, and ethnicities, and stories here. I like to think that I know a bit about the area, but today, I'm trying to surprise myself. I'm going on a walk to meet experts, artist, and enthusiasts who can tell me something new about the Bloomsbury group. The collection of influential and gifted writers, intellectuals, philosophers, and artists, particularly the artists. Their work and outlook deeply influence literature, aesthetics, as well as modern attitudes towards feminism, sexuality, and even interior design. There was a saying about them, "They lived in squares and loved in triangles."

Well, we will speak about the significance of the triangles later, but one of the squares they lived in was the one I'm sitting in the center of now. Gordon Square WC1. One of the people who lived in this square, the great novelist, Virginia Woolf wrote, "No need to hurry, no need to sparkle, no need to be anybody, but oneself". I'm setting out to discover what that independence meant to them, and what it could mean now to us, in Contemporary, London. Before I started exploring Bloomsbury's bustling streets and leafy squares, I've visited Tate Britain, to meet up with Clare Barlow. Curator with the exhibition, Queer British Art. I wanted to find out about Bloomsbury's unique place, and history of LGBT visual culture.

Clare Barlow: [unintelligible 00:02:10] of 1920s through to 1960s, you're in a period in which sex between man is illegal, but sex between women is not really known about or really frowned on. This creates huge secrecy and silence. Bloomsbury is one of the most radical experiments in modern love. They're all very close friends, they're lovers, and that is certainly true of some of the most famous Bloomsbury relationships. Such as that between Duncan Grant and Vanessa Bell. Grant and Bell lived together at Charleston house. Bell is married to Clive Bell. He doesn't live with the family. Grant an Vanessa have a child together, but Grant also, some of his really important boyfriends come and stay. This really captures the sense, but this is a circle which is both artistically incredibly creative, but also is really trying to scrutinize model life, and think, "Is there a better way of being, a better way of doing things?"

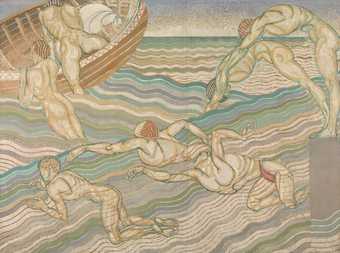

It's very hard to know how far the wider public is aware of a relationships within Bloomsbury. Certainly, someone like Duncan Grant is absolutely extraordinary in his exploration of queer intimacy. He's somebody who is really capturing the domesticity of queer life, to an extent that you don't really get in anyone else's work until someone like David Hockney. Actually, people do see something in Duncan Grant's work at that time, which they find very shocking. Duncan Grant's Bathing from 1911, which is a commission for Borough Polytechnic. It's quite flat, because figures where the anatomical form has been quite simplified, swimming in the water, diving or preparing to dive, and then on one side of the canvas, there's two figures clambering into a boat. The faces are left blank, although we can speculate relationships between them. It's very much left to the viewers imagination.

When it's first installed, the National Review describes the painting as a nightmare. Standing in front of that painting, it's almost impossible to see what the reviewer is seeing. Part of the reason is to why it provokes this reaction is that Grant is basing it on figures swimming in the Serpentine, the Serpentine is a popular cruising spot. This idea of cruising by the river, picking up potential lovers, is something which he expose in other works, such as his Bathers by the pond. And for me, Bathers by the pond is the much more explicite work. You have lots of nude man sunbathing, some of them bathing, and the glances that they're exchanging are positively electrifying. One of the things that I think is the whole mark of Grant's character, something he said which his daughter describes as being one of his favorite magazines is, "Never be ashamed."

There is a kind of honesty in the way that Grant lives his life. If he is attracted to someone, he's interested in sleeping with them. There's a complete refusal to live within the narrow parameters of what is permissible for male intimacy, or what is permissible for friendship. I think that kind of easy openness, engagement, and support is a really important aspect of what holds Bloomsbury together.

Bonnie: I've just walk over to the Tavistock Square, and I'm standing in front of the bust of Virginia Woolf, reminded of what she wrote about the composition of her novel To The Lighthouse, how she walked around Tavistock Square, thinking about it, how it came to her. You can still actually believe that to be true, it's still a leafy, beautiful place we pose, quiet. Virginia lived here with her with her husband, thinking about her sister Vanessa Bell, the great artist, and how the two of them in their own particular disciplines really began to look at the place of women in the 20th century.

[background conversation]

Bonnie: Writer and art historian Kathryn McCormick has come to join us here in the rustle and buzz of Tavistock Square. She tells me how Virginia Woolf and Vanessa Bell, in rebellion against their beautiful mother, set out on radically new artistic paths.

Kathryn McCormick: The girls lost their mother in 1895, Julia Stephen. This paragon of late Victorian beauty and femininity past away, and Vanessa Bell being the eldest sister, had to take on this identity of something that was called the Angel in the House. The Angel in the House was pious, obedient, self-sacrificing, totally without interest for herself. If we think about Julia Stephen, the Pre-Raphaelite beauty, feminist don't really like Pre-Raphaelite painting, because the women look drugged, heavy lidded, they're these object set to silent and creep around--

Bonnie: Everyone is dying in a way. [unintelligible 00:07:50] all the dying.

Kathryn: They're dying, exactly. Being strangled by their [unintelligible 00:07:54], because they haven't paid attention to the [crosstalk] and all of that kind of things. So, it's the type of beauty that 20 years later got completely dismantled, and then you get to portraits, for example, of Iris Three, and she has this glamorous shock of bobbed, fringed, blond hair, and eyes that are sparkling and bright, and especially the way Vanessa Bell portraits are, she fills the canvas, almost most like that picture of Henry VIII that we're really familiar with, with this--

Bonnie: [unintelligible 00:08:25] look, yes.

Kathryn: Absolutely, and it's so possessive of the space, it's so affirmative of her presence of being a woman who is being observed by another woman, and not being to pick to as passive object, and she does represent a different ideal of feminine beauty, that is the absolute opposite of the Angel in the House, Julia Stephen. Vanessa Bell, in terms of painting, you see her way of converting her domestic world into something that expressed to new visual language, and she picked up the current of things that were happening in Europe.

She visited Paris in 1914, she visited the studios of Picasso and Matisse, and was very much influenced by their new visual language, which was the language of abstraction. The domestic becomes the space where they work, no longer the space of what we might think of now as oppression, but becomes a space where they can explore their new language, for Virginia in the literary sense.

For Vanessa Bell, the paintings that she made in that early period after Paris where entirely abstract. To me, the yellow background of Composition in 1914, could have started as something like a vase of flowers. Flower painting was a discrete hobby for lady painters as they were called, and she's turned it into something which is a dynamic experiment with color and simplified form.

Bonnie: And the seated pieces. The figures were setting, but we don't see their faces.

Kathryn: Portraits, yes.

Bonnie: That is, again, their mother was so painted.

Kathryn: For me, that is the most interesting part of Vanessa Bell's work. It really jumped out the importance of thinking about that, because that blankness, that empty space leaves so much to the imagination and interpretation, that it becomes less about superficial beauty, and more about the space perhaps behind the eyes, what's going on in the internal and that's very, very radical for the time, and especially in Britain. Maybe leads us to think about the interior world of a women, which is something that we're very interested in now with writers, people like Elena Ferrante, Deborah Levy. I think Vanessa Bell was doing that, alongside her sisters experiments in writing at the beginning of the 20th century. There's not a big distance, there's not a big gap.

It was through those portraits of those blanked out faces that I thought this is something really important and special that we need to recognize, and that we need to think about and talk about, especially because it's so relevant right now. The continuing, commercialized faces of women that we see in advertising, in social media, the way people try to make themselves look like pictures on different social media channels, and I think it's very useful for us to look back to what Vanessa Bell is saying about femininity, the potential of femininity is being something that's beyond the surface and looking inside to something that's very powerful, because it's the unknown.

Bonnie: Take the face away.

Kathryn: Take the face away, and you have something that can't fix. We can frame those women in a picture like her mother was framed. It's unsettling a little bit, because we don't know what's going to come out of that face. We can never really get that.

Bonnie: Maybe what we see is our own face at the end.

Kathryn: Absolutely, there's always the potential for the mirror, maybe that's what we look for, absolutely.

Bonnie: Thank you Kathryn McCormick. Thank you.

Kathryn: My pleasure.

Bonnie: I found it hard to believe that the Bloomsbury Set were really radicals. A century later, their wealth, their lifestyles, the clothes they create, it seemed to me to be aristocratic and exclusive, but meeting Ellie Jones, a PhD student from Kings College London, went a long way towards changing my mind. She explains how the Bloomsbury's, especially Duncan Grant, entered into a uniquely open and intimate relationship with the art and culture of people of African descent living in London.

Ellie Jones: The kind of influence that black artist has on western art is far more well known in terms of New York and Paris. The London story is far less well known. At the same time, we knew that our performers in London, who have been photographed by white photographers. It was just the case of pursuing that, and delving deeper. Then through that, these stories have been uncovered.

Bonnie: The Bloomsbury Set were wealthyish people, so there would have been some colonial activity back there in their family.

Ellie: Grant's family have a colonial past. He was born in India. You see these complexities in their art. Grant in someways perpetuate this colonial vision of a black subject, sometimes. Other times you see the relationships between an artist and model is far more complicated in that. These people had far more agency than just being a colonial subject to Bloomsbury. Intimacy in relationships are incredibly important, and to focus on the way that he portrays intimacy, I looked at his private drawings, a lot of them depicted interracial couplings. Some of them are scenes of group sex, some of them are just cuddling. He drew them obsessively over a decade. He would pick up anything that was just lying in the studio. Some of them are done on the back of a newspaper, some of them are done on receipts, because he did hundreds of them, it's almost like he is trying to capture something that's very fleeting, which intimacy is.

It's interesting and really important that they are interracial, and not just, "I'm a white artist drawing a black body."

Bonnie: What I find moving is that there were friendships, there were real, real bonds.

Ellie: I think one of the most important relationships for Grant in his later life was with man called Pat Nelson. There were hostels in Tavistock Square, which is where Carribean students would stay. He was around Bloomsbury in the late '30s and he took a work as an artist model. It's not known exactly how him and Grand met, but they became lovers, even though their romance ended they maintain a very strong friendship. Gemma Romain has written a biography of Pat Nelson, and she's done a lot of research tracing his life through Tate's archives, through his letters to Grant. Nelson joined the military in 1940 and then became a prisoner as war, and Grand was listed as his next of kin. I think that really demonstrates the closeness that they had.

He was very traumatized after the war. I think he moved back to Jamaica for a period of time, and then in the '60s he was back in London. Grant did a portrait of him, and it's a really affectionate portrait. He's older, he's sat in a chair, he's very comfortable in himself, his clothes, what makes a change. [laughs] Some paintings that Grant did and was really touching is, he has a scarf, slung over his shoulder, and it's an Omega Workshop fabric. Whether it was a gift from Grant or whether he just thought, "I'll wear it for the sitting," regardless it's a symbol of that bond.

Bonnie: You see, an earlier portrait where he looks like a dancer, the beautiful torso, and arms above his head, beautiful face. This is quite extraordinary in a way, because this just say there were leaps and bounds that they had to make. Is there an impact or was there and impact that lasted?

Ellie: It wasn't just Pat Nelson, Grant associated it with the Ballets Negres, which was the first black ballet company to be funded, not just in Britain, but in Europe. Grant would have been associating with this ballet company at the time when he was doing all of these drawings. The drawings really show grants endless curiosity of the ways to present the male form, and dance is very important and exploring the possibilities of the body, and the ways that it can move, but this influence just isn't known.

Bonnie: People of African descent represented modernity, didn't they? They represented the urban, they represent getting away.

Ellie: A lot of British artists were looking at Hallam in particular immediately after the war, prejudice still persisted for some people and it would be wrong to ignore that, but at the same time, you're absolutely right. It was modernity, that what it was. I think for some artist, they associated blackness with Africanness in a way that was incredibly problematic and that it was primitive. For others, they recognized that it could be incredibly innovative, and it was a way to break through with decimation that had occurred after World War I.

[background conversation]

Bonnie: I've returned to Gordon Square, back where I started, to discover more about the world, connecting everything I've encountered on this walk. The world of the home.

[background conversation]

Bonnie: I want to explore the intense interest of the Bloomsbury in domesticity, [unintelligible 00:18:03], safe places, and which to experiment with their often genuinely radical ideas about living.

[background conversation]

Bonnie: Maybe in their homes, we can find a place to tie up the many threads of their lives. I joined Dr. Darren Clarke, the rousing Head of Research, Collections and Exhibition at Charleston farmhouse, the Bloomsbury surviving country home. We also hear from the artist Sophie Coryndon, who considers the radical, practical and artistic sides of life in a Bloomsbury interior. I'm in one of the wonderful houses in Gordon Square. Are we at number 46, down to Keynes house, or we're somewhere else? I thought-- [laughs]

Darren Clarke: We are actually next door to 46, and we're in [unintelligible 00:18:58] Keynes library.

Bonnie: If you can tell us who originally lived in number 46.

Darren: In 1904, 46 Gordon Square became the home for four siblings, for Vanessa, Virginia, Adrian and Thoby Stephen. Vanessa would later become Vanessa Bell, the artist. And Virginia Stephen would later become Virginia Woolf. They have been living at the Hyde Park Gate, which was the home of their parents. Their father died in 1904, their mother would have died nine years before. They were giving the freedom then to escape from their childhood home, and to set up a new home together.

Bonnie: What kind of home was in Hyde Park, because you used word "escape", what was it like, and what were they trying to do?

Darren: It's very, very tall, the street was very narrow, was very dark, and the inside was very Victorian, black pant and red velvet. It was full of three families things, as well as the Victorians with accumulations of objects.

Bonnie: What did Gordon Square represent? I imagine being who they were, they chose Gordon Square.

Darren: In Hyde Park Gate you look out the window, you can see the neighbor washing her neck. Whereas here in Gordon Square looking out through the windows of Keynes's library and you can see trees, you can see space and you can see light. It's almost like moving to the countryside, but at the same time it was much more vibrant too, it was noisy, you could hear the streets, you could hear people. You felt like you were at the center or something.

Bonnie: How did painting a wall become part of what they were trying to do?

Darren: I think there are gradations of radicalism. In 1904, they were moving from this really heavy interior, they came in and they whitewash the walls. They got rid of most of the furniture. I think that is reflected in the way that they started to think as well. You could get rid of the clutter of thought, you could get rid of the clutter of domesticity, and you could get rid of that clutter of expectation of behavior at the same time. In Hyde Park Gate they have their bedrooms, but they didn't have any other private space. Having their own rooms, having their own spaces to work in really freed them up to actually start having control of their creativity.

It allowed them to entertain the people they wanted. They could have Adrian and Thoby's friends from Cambridge to come along, almost have a open house. Rather than them having to mind their P's and Q's and to be very polite, and to entertain, but not dominate a conversation or to express an opinion. Suddenly, they were with young men who [unintelligible 00:21:38] enticed by them as women, who would treat them as the fellow undergraduates.

Sophie Coryndon: You think we had learn to show our personalities through our interiors. Yet, you often go into interiors that you can't really get a sense of the personality that lives there. I think it's wonderful when you walk into a room and you get a sense of the person that lives or lived there. That's a wonderful thing. It's something I would want to leave as a legacy. I don't get the impression that was for anyone other than themselves. It was their stage set, it was their backdrop. The actual fact, a lot of the the painting is very much like a stage that it was done very quickly with acrylic and oil, and mixed together and conserves his nightmare, but that was the whole point, it wasn't meant to last. No one was thinking about it in those terms. They were thinking, "Well, let's just pop something on there and then tomorrow if we don't like it we'll pop something else on there." It was never meant to be anything other than a backdrop to their slightly colorful lives.

Darren: There's a radical change in 1910, which is the year that Roger Fry put on the First Post-Impressionists Exhibition and that affects interiors really dramatically. The First Post-Impressionist Exhibition brought together works by Van Gogh, Gauguin and Cezanne. It was a challenge to this patriarchal establishment, but it really excited and invigorated this younger generation of artists, including Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant. It changed the way that they were working, it changed the way that they thought about art. This was followed up a couple years later by the Second Post-Impressionist Exhibition, including works by Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant. A few months after the Second Exhibition closed, Roger Fry set up the Omega Workshops with Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant, as co-directors. He really wanted to get that Post-Impressionist aesthetic outside of the picture frame and into people's homes.

You could go to the 33 Fitzroy Square and you could choose textiles that have been designed by Vanessa Bell, Duncan Grant. You could buy carpets, you could buy children's toys. You could commission whole rooms. They would all be in these really bright colors, and these really strong patterns. It comes to breaking down of Art and Design, so that art doesn't stop at the picture frames, it fills the whole room, fills your whole life.

Sophie: I rather love the honesty with which they would sit on a chair, paint a chair and then paint the chair into the painting. It's the layers of art. It's the layers of creativity. There's a divide. There's craft. There's art. There's design. The truth of the matter is they all overlap anyway. Of course, they do. The interesting bit is the cracks in between. And so with Omega, the fact that they were being allowed to be artists and designers, it wasn't frowned upon, it was just a way of making money. I don't know whether other people outside of that frowned on it, or their artwork would have been denigrated by having done design work. Certainly, that can be the case now, and I find that ridiculous and slightly short-sighted.

Artists have always had to do other things certainly at the beginning of their career to make money, to facilitate making their art. They broke rules, but it wasn't so revolutionary. Yet, of its time, it really was. They were kicking against their time. Bizarrely, now, a way you think everything is so free and fluid, it's not. We're still kicking against these boxes of you paint, you sculpt, we're still talking about them now. Probably for those reasons, not necessarily because they were brilliant artists. It's more because of what they represented and what they were doing and how they did it.

Darren: The plate you eat your dinner from should be as beautiful and as aesthetically pleasing as the painting on the wall. Charleston is a home and you can see we've got a beautiful big painting by Vanessa Bell, Clive Bell and Duncan Grant sitting in the garden [unintelligible 00:25:36] Charleston just after the Second World War.

Bonnie: Look at that.

Darren: That looks like a nice evening in with a couple of empty bottles of wine, and a lot of books and some good conversation going on, with a Picasso on the wall and a Matisse as well.

Bonnie: And they do like human beings.

Darren: Absolutely, yes, in their slippers.

Bonnie: On my journey through Bloomsbury, I've come to appreciate the Bloomsbury Set in a new and much more vital way. Although, to our eyes they can seem distant, exclusive, removed from the world [unintelligible 00:26:17] London [unintelligible 00:26:18] concerns. In many ways their lives could be a radical inspiration, even today. Their rejection of easy, conventional ideas, and they're all out of attempt to find new ways of being, in art and in life. Give them a significance for my life that I've never fully appreciated before. I'm even happier being a Bloomsbury local, knowing I share the streets with these creative and very independent ghosts. They really tried to do something, and it's so wonderful.

Darren: Very proud of them.

Bonnie: It's wonderful. I feel very moved by them, I really do. I wish I could speak longer about them. If you enjoyed the episode, please write a review and subscribe. We'll be back next week with another Walk of Art. If you want to explore some of the areas of London yourself, take a look at the accompanying Walks of Art book on the Tate web site.

[00:27:37] [END OF AUDIO]

Explore Bloomsbury

Follow in Bonnie Greer's footsteps and discover the sites yourself.