Vanessa Bell

Studland Beach. Verso: Group of Male Nudes by Duncan Grant

(c.1912)

Tate

Vanessa Bell, Roger Fry and Duncan Grant were central to the formation and activities of the Bloomsbury Group. They were also the key artists in the group and their art has defined what we think of as 'Bloomsbury'. Find out about their shared ideas and inspirations and explore the development of their individual artistic styles.

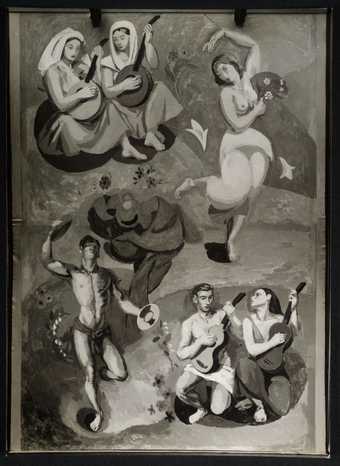

Painting together

From 1911, when they became close friends, Vanessa Bell, Duncan Grant and Roger Fry often worked together painting the same things. Subjects included friends, (Lytton Strachey and Iris Tree were painted by all three artists), interiors and still-lifes.

These two paintings were painted side-by-side by Grant and Bell in 1914. The paintings show slightly different views of the same mantelpiece in Vanessa’s Bloomsbury home.

Duncan Grant

The Mantelpiece

(1914)

Tate

Vanessa Bell

Still Life on Corner of a Mantelpiece

(1914)

Tate

Although the paintings look similar there, are clear differences. Grant painted the moulding under the corner of the mantelpiece more exactly, whereas Bell simplified the scrolls to rectangular shapes. They chose different colours for the boxes, flowers and even for the background wall. Grant also added cut out pieces of painted paper to create a collage effect.

Separate paths

After 1915, when Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant had become closer, the three artists rarely painted together. Fry felt excluded and complained in a letter to Clive Bell:

In painting Nessa and Duncan have taken to working so entirely altogether and do not want me…I find it difficult to take a place on the outside of the circle instead of being, as I once was, rather central.

However, a few years later Vanessa Bell felt that working so closely with Grant had was having a bad effect on her work. On holiday in St Tropez in 1921 they decided to paint separately, and only look at each other’s paintings at the end of their stay. From that point although they sometimes worked together or painted the same subject, but usually went their separate ways.

Shared adventures into abstract art

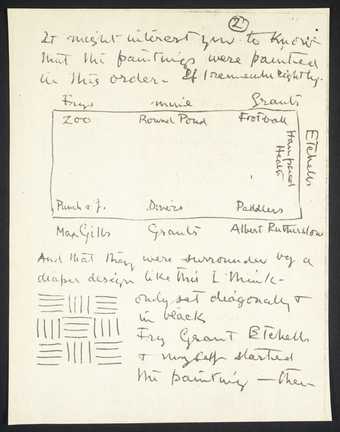

Fry, Grant and Bell all experimented with abstract art between 1914 and 1916. They used blocks of colour and sometimes experimented with collage.

Vanessa Bell

Abstract Painting

(c.1914)

Tate

Roger Fry

Essay in Abstract Design

(1914 or 1915)

Tate

Duncan Grant

Interior at Gordon Square

(c.1915)

Tate

Vanessa Bell: Techniques and experiments

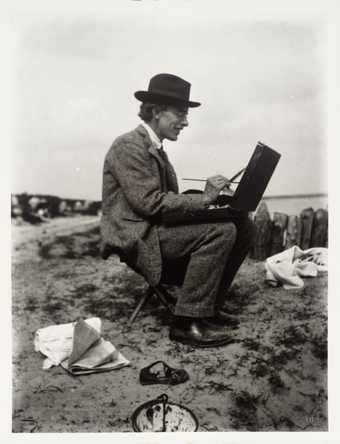

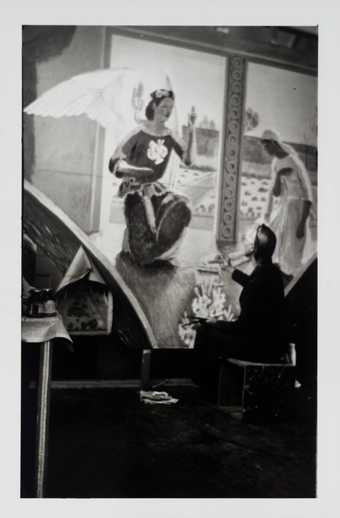

Vanessa (Stephen) Bell painting Lady Robert Cecil 1905

© Tate Archive

Early work

As a student at Royal Academy Schools where she went to study art in 1899, Vanessa Bell was taught by John Singer Sargent. She was also greatly influenced by the paintings of James Abbott McNeill Whistler.

James Abbott McNeill Whistler

Nocturne: Blue and Silver - Cremorne Lights

(1872)

Tate

In a letter to her friend Margery Snowdon written in 1905 she described the influence of Whistler’s technique on her painting style:

You see my method is the same as Whistler’s – only he used many more layers than I should because he painted very thinly – which I cant, now at any rate, get myself to do. But the important point, which I believe I haven’t realized before, is that he didn’t put the right colour on at once. It was probably almost a monochrome to start with & I suppose he only got the right colour at the end – I expect that the most beautiful surface is got in his way – but I cant paint thinly enough to do that for one thing – and also in sketching I am not sure that it would be possible.

Letter from Vanessa Stephen (Bell) to Margery Snowdon, [14 Aug 1905]

Towards abstraction

Vanessa Bell painted some of the most radical paintings produced by the Bloomsbury Group.

She was encouraged by her friend Roger Fry who introduced her to post-Impressionism and the work of painters such as Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso. This had an explosive effect on her technique and use of colour.

As for us we’re in a huge state of excitement having just bought a Picasso for £4. I wonder how you’ll like it. It’s “cubist” and very beautiful colour, a small still life.

Letter from Vanessa Bell to Virginia Woolf, 19 October, 1911

In Studland Beach, which Vanessa painted in 1912, the people and landscape have been dramatically simplified. The crouching figures, beach houses and seascape are shown as flattened shapes and broad bands of colour.

The Bell family on Studland Beach © Tate

Vanessa Bell

Studland Beach. Verso: Group of Male Nudes by Duncan Grant

(c.1912)

Tate

In a review for a 1930 exhibition catalogue, Vanessa Bell's sister, the writer Virginia Woolf, described the feeling she got from Vanessa's paintings. Although written thirty years later she could be talking about Studland Beach:

No stories are told; No insinuations are made. The hillside is bare; the group of women is silent; the little boy stands in the sea saying nothing.

Virginia Woolf, Recent Paintings by Vanessa Bell, Cooling Galleries, 1930

In the same year Vanessa Bell painted two artist friends, Frederick and Jessie Etchells, painting. Their faces are left blank without detail. Blocks of loosely-painted colour suggest the background.

Vanessa Bell

Frederick and Jessie Etchells Painting

(1912)

Tate

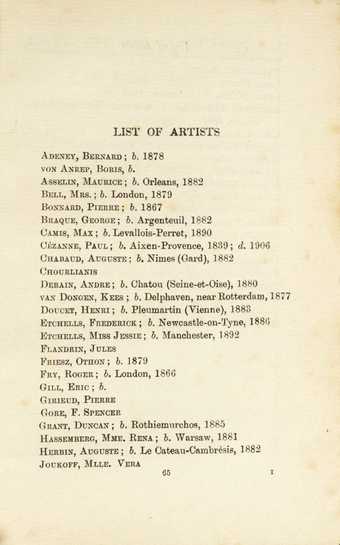

In these paintings Vanessa Bell emphasises form over content (what the work looks like over what the subject of the painting is). This is the main theory of modernism. Four of her paintings were included in Roger Fry’s Second Post-Impressionist Exhibition in London in 1912, where they hung alongside artworks by Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso and André Derain.

List of artists included in the Second Post-Impressionist Exhibition at the Grafton Galleries in London. Courtesy Tate Archive

Vanessa Bell

Abstract Painting

(c.1914)

Tate

Vanessa Bell also experimented with total abstraction. In Abstract Painting painted in around 1914, she used blocks of colour to build up her design. In doing so became one of the first artists in Britain to paint in an abstract style, confirming her position as a leading modern artist.

Vanessa Bell

Mrs St John Hutchinson

(1915)

Tate

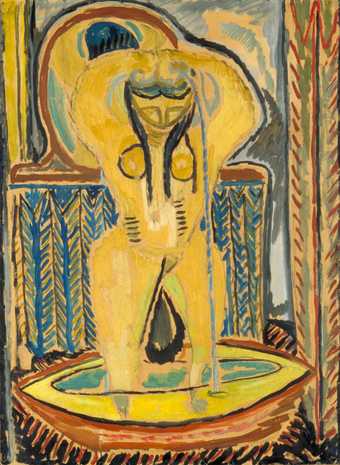

The influence of abstract art can also be seen in the backgrounds of figurative works. For example in her portrait of her husband’s mistress, Mrs St John Hutchinson 1915, background strips of colour are used add structure to the work. The Tub painted in 1917, has a simplified abstract background. With The Tub we also see Bell returning to a more figurative style. A letter to Roger Fry of 1918, provides a glimpse into her approach:

I’ve been working at my big bather picture and am rather excited about that. I’ve taken out the woman’s chemise and in consequence she is quite nude and much more decent.

Letter from Vanessa Bell to Roger Fry, 1 January 1918

In a photograph of an earlier version of the painting, the bather is still wearing the chemise.

Vanessa Bell

The Tub

(1917)

Tate

![Mary Hutchinson with Vanessa Bell's painting, The Tub, [1916] © Tate Archive](https://media.tate.org.uk/aztate-prd-ew-dg-wgtail-st1-ctr-data/images/maryhutchinsonwiththetub_1_y6CTlkm.width-340.jpg)

Mary Hutchinson with Vanessa Bell's painting, The Tub, [1916]

© Tate

A more traditional style

The 1920s and 1930s saw Vanessa Bell returning to a more traditional painting style.

Vanessa Bell

Interior with a Table

(1921)

Tate

She and her close friend Duncan Grant spent much of their time in Cassis in the South of France, where they enjoyed the quality of the light. During this period, Bell started painting in a more realistic style. Her brushwork became tighter and neater and her use of colour was toned down. She describes these changes in a letter to Roger Fry, with perhaps a hint of regret.

I think Duncan and I have changed extraordinarily over the past 10 years or so I hope for the better. But also it seems to me there was a great deal of excitement about colour then – 7 to 10 years ago – which has perhaps rather quieted down now I suppose as a result of trying to change everything into colour… I wonder now whether we couldn’t get more of that sort of intensity of colour without losing solidity of objects and space.

Letter from Vanessa Bell to Roger Fry, September 19 1923

Vanessa Bell also became relatively successful around this time. She had her first major solo exhibition in 1922, and three further solo exhibitions. For one of these, at the Cooling Galleries, her sister Virginia Woolf wrote the catalogue introduction.

But Mrs. Bell has a certain reputation it cannot be denied…She is reported (one has read it in the newspapers) to be ‘the most considerable painter of her own sex now alive’… whatever the phrase may mean, it must mean that her pictures stand for something, are something and will be something which we will disregard at our peril. As soon not go to see them as shut the window when the nightingale is singing.

Virginia Woolf, Recent Paintings by Vanessa Bell, 1930, Cooling Gallery

Vanessa Bell continued to paint portraits, landscapes and interiors for the rest of her life. But gradually lost her place as leading modern artist as new radical movements such as surrealism and Unit One emerged.

Duncan Grant: A European artist

From the early moody portraits of friends to his bold experiments inspired by Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse, Duncan Grant’s style was greatly inspired by the art he saw around him and on his travels.

Early influences

At Westminster School of Art where he studied from 1903, Duncan Grant became interested in the art of James Abbott McNeill Whistler, Edgar Degas and the impressionist painters. He was encouraged by a family friend, the artist Simon Bussy, who advised Grant to look and learn from the style of old master artists. (‘Old masters’ are respected artists from the past). Bussy also advised Grant to paint every day – which Grant did for the rest of his career.

The influences of Degas, Whistler and Bussy can be seen in the atmospheric mood of the portrait of Lytton Strachey which Grant painted in 1909.

Duncan Grant

Lytton Strachey. Verso: Crime and Punishment

(c.1909)

Tate

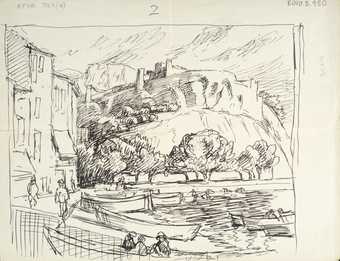

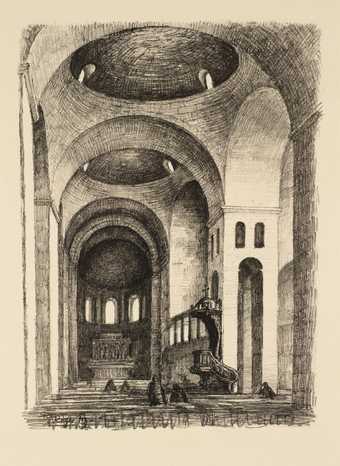

Travels and inspiration

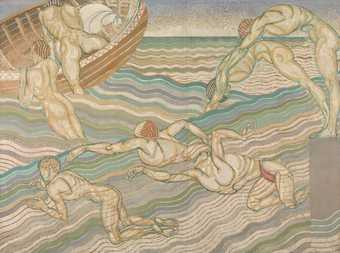

In 1903 Grant had a sudden revelation. He tells the story that a voice directed him to go out into the world and learn all there is to know about painting. He made trips to Italy where he copied paintings by early Renaissance artists Piero della Francesca and Masaccio. He also travelled to Greece and turkey where the colour and design of Byzantine mosaics excited him. These Italian and Byzantine influences can be seen in paintings such as Dancers.

While studying in Paris in 1906, Grant visited the Louvre every day. (The Louvre is the national art museum in Paris). There he copied paintings by Chardin, Poussin, Rembrandt and Rubens. In Paris he also saw work by the impressionists at the Durand Ruel and Luxembourg galleries.

In this audio clip Duncan Grant shares his memories of these student days in Paris: