Marcel Duchamp

Fountain

(1917, replica 1964)

Tate

© Succession Marcel Duchamp/ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2023

Comedy as an art form can be traced all the way back to ancient Greece. From toilet humour and sarcasm, to irony and wordplay, artists continue to use comedy within their work today. In this episode, comedian Charlie George explores how artists have used comedy throughout art history and asks 'can art be purposefully funny?'

Hear from artist Abondance Matanda, art historian Alice Procter and assistant curators James Finch, Helen O'Malley and Katy Wan as they chat about their thoughts on comedy in art from Tate's collection.

This episode was a Stance Media production for Tate, produced by Phil Brown, researched by Deborah Shorinde and executive produced Chrystal Genesis.

Want to listen to more of our podcasts? Subscribe on Acast, Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts or Spotify.

Charlie George: An embarrassing confession to start us off. I used to go to Tate Modern and sit in one of the quiet rooms full of paintings for inspiration to write terrible brooding poetry, waiting to meet the love of my life assuming it would happen in this very moody and serious way. I'd always get really annoyed by children running in, laughing, and making fart noises, but actually, why isn't that also a completely valid response to art? Is it okay to laugh in galleries? I'm on a mission to find out if art can be purposefully funny.

Speaker: The. Art. Of.

Charlie: Hello, I'm comedian Charlie George. Welcome to Tate's podcast The Art Of, a series telling the human stories behind works of art. In this episode, we're exploring the art of comedy. [laughs] Oh, dear. My quest begins at Tate Modern. I just keep thinking of the word avocado, which is not helpful to me right now and I wish my writer was more competent. No matter where in the world you go or what language you speak, anything to do with our toilet habits seems to get a lot of us laughing.

Helen: It is quite a beautiful shape. It's got this really pristine finish.

Charlie: I'm with Helen O'Malley, assistant curator at Tate.

Helen: It's quite feminine, really beautiful curves.

Charlie: It doesn't scream like a place where you would put your genitals. It could even be a fruit bowl potentially, but you'd want to wash that fruit.

Helen: We were moving into new territory now, yes. Although I'm not opposed to it.

Charlie: It's a piece that many of us will have seen unknowingly in our lives at some point kind of etched our mind of a urinal in a gallery? It's Fountain by Marcel Duchamp.

Helen: Essentially, it is a manufacturer's porcelain urinal that Duchamp has laid on its back. The replica, which is on display at Tate is a glazed earthenware that was painted white and the signature is reproduced in black paints in the bottom left corner, and it reads R Mutt 1917.

Charlie: Who is R Mutt?

Helen: That's a tricky one because some people think that it was a pun on the German word armut which means poverty. Also, some people think that maybe it was a reference to the JL Mott Iron Works company, which was a really well known sanitary equipment manufacturer at the time. There was also a cartoon strip at that time called Mutt and Jeff and some people think that Duchamp was alluding to that.

Charlie: Did he make the original urinal himself?

Helen: The original, I suppose it was already made and that it was purchased from a company. He didn't hand make the urinal, but it's the artwork, the object itself, or is it the idea. When he flips it onto its back, well, it's no longer functional in its original sense, it becomes something new, and when he gives it that new title, again, it transforms into something. Even just his decision not to place it on the wall but to place it on a plinth. Plinths are normally, we see them in museums, galleries to represent very valuable, priceless artwork, so when he places the urinal on that plinth, he's making a statement.

Duchamp was a French artist, but he relocated to New York in 1915. He was one of the founders of the Society of Independent Artists in New York, which was a new organization that was incredibly open and had a very democratic ethos. They had an annual exhibition and all submissions were included in the exhibition, but it seems like Duchamp was maybe questioning whether the board members and the society itself were actually as open as they were suggesting. So he made the decision to submit an entry under a false name and that was the fountain, that was the work that he submitted as R Mutt, but then after the exhibition, it was lost. The only trace we have now is a photograph that was taken by Alfred Stieglitz of the original. In the 1960s, Duchamp issued a number of replicas that are in various public collections around the world.

Charlie: Oh, cool, what a great story behind it. What a cheeky nightmare? Basically, it's like, "Oh, we're really open to anything." "I'm going to send you a toilet, what do you think about that?" It's nice. That's a nice statement, isn't it?

Helen: Yes, it's pretty provocative as artworks go, and I think he was definitely trying to push the boat out, he wasn't shy in his approach.

Charlie: I wondered what you thought about whether or not he intended this to be funny, and if you could tell us a bit more about the intentions of this artwork from the artist?

Helen: I think he intended to cause a stir, and he understood that humour or comedy could be a tool he could use to make his point. In 19, I think, '64, in an interview, he said that he chose the urinal in part because he thought it will be or would have the least chance of being liked. He understood that contrast. He knew that it would cause a stir, and he knew that it would cause a laugh, and I think he was trying to take that and to capitalise on it.

Charlie: Do we know if it went well with the public when it was originally made? What did people think of it?

Helen: There were mixed reviews. The key thing is that the public never got the opportunity to see it because the board was so appalled by the work following its submission that they made the decision to exclude it from the show, but it did cause a big stir. There was a lot of press coverage and discussion following the opening up the show with what lived on in a more conversational way.

Charlie: I wonder, what if they were just fine with it? That would have been a very different story.

Helen: Absolutely, and again, I think that's why in the '60s, he was so willing to create replicates because, for him, the original object isn't important, it's all about the conversations that it provoked and the conversation that it started.

Charlie: Is it okay for people to laugh at it? If I saw this in a gallery, I think it would spark conversations about it, and if I was with a friend, let's be honest, say, I was walking around the Tate, and I do this a lot, if I see something, my first response would probably be to take the Mickey. How appropriate is that? Is that his intended point is for people to actually laugh and have a response?

Helen: I think so. Artists are so subjective. As far as I'm concerned, anything goes, but I completely take your point. There's a toilet in every home in Britain, so what makes this one so special? Again, I think the interesting thing about seeing the work in a gallery, and this goes back to Duchamp again because he decided exactly how to present it, but when he flipped it onto its back, it's not immediately recognisable I suppose, it takes a second for the penny to drop. When you realize what you're actually looking at, the first thing to do is laugh. It's almost impossible to resist.

Charlie: I'm really interested because I used to do some performance work and I remember reading, not a great deal, but a bit about Dadaism, and I wondered if you could tell us a bit more about the phrase anti-art and that whole movement?

Helen: Anti-art was a phrase that, well, we believe Duchamp coined it around 1913 when he made his first ready-mades, which were artworks that were created from manufactured, mass-produced objects. It's a term used to describe art that challenges the accepted, I suppose, definitions of arts. It is associated with Data, which was a movement that took off in Zurich and simultaneously in New Yorker around 1916. It was really a response, at the time, to capitalism, to nationalism, and even corrupt politics, which many artists believe led to the First World War. Politically, they were disenfranchised and they were using their work to process those frustrations. They were questioning the establishment by abandoning all reason and logic because they felt like what was happening in the world politically was completely unreasonable, and the fighting, what leads into that. It's a difficult thing to do. People, I think, overlook the power of humor within art, but it's really difficult to get the right balance, it's incredibly difficult to be that impactful, and he really manages to achieve that, I think, with the urinal. The humor is dark, it's dry, but it's incredibly powerful. It makes a real impression, and it stays with you. You go away asking like what is art? Really, what is it? Why can't the urinal be art?

[music]

Speaker: The. Art.Of.

Charlie: Although I remember needing the toilet quite often when I went to art galleries when I was a kid, one thing I don't remember seeing was work by women artists of color on display. This is something, as a child looking for role models, I longed for since I first discovered that my Pocahontas Barbie was in fact modeled on the face of Christy Turlington, a white model. Where we're all the women of color. The next two pieces we're looking at tried to tackle this question. They're by the Guerrilla Girls and are called Dearest Art Collector, and the advantages of being a woman artist. Before I speak with another artist about the impact of them on her, here's Helen again.

Helen: The Guerrilla Girls are an anonymous group of female artists who use their work to highlight sexism and racism within the art worlds.

Guerilla Girls: If art is a record of culture, and the art doesn't look like the culture, and the art is told only through the works of white males, that's basically what it is. It's the history of patriarchy, not the history of who we are.

Charlie: This group, they actually wore a gorilla mask, can you tell us what the reasoning behind this was?

Helen: The reason they wore the masks was, well, firstly, to protect their identities, but a better answer to your question is that they wanted to remain anonymous in order to keep their focus on the issues.

Guerrilla Girls: There was discrimination right in front of people's noses, but they didn't see it. It occurred to some of us that the art world was basically a white male place and no one asked why.

Helen: We don't know exactly how many members, the number a hundred is a decent estimate, I suppose. Members have come and gone over the years. Two of the founding members are Frida Kahlo and Kathe Kollwitz, or at least those are the pseudonyms, and they're still active in the group.

Guerrilla Girls : It was a lot of fun, especially when you're anonymous, and you wear gorilla masks.

Helen: As well as wearing the gorilla masks, the members also adopted pseudonyms of deceased artists or creatives. They did that because they wanted, again, to highlight the work of women that had been overlooked in the past.

Guerrilla Girls: The white male artist said, "I can't tell my gallery what to show," and the galleries said, "I can't show women because their work doesn't sell," and then collectors would say, "I can't buy women or artists of color because I don't see them." Everyone was passing the buck to someone else.

Helen: There were many factors that led to their formation, but one of the really key events was an exhibition that was held at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1984.

Guerrilla Girls: Out of close to 200 artists in the show, there were only 17 women and even fewer artists of color.

Helen: They made the decision to stage a protest outside MoMA.

Guerrilla Girls: Placards, and chanting, and picket lines.

Helen: Unfortunately, the protest didn't really generate the traction or the awareness that they were hoping for.

Guerrilla Girls: The only thing that we accomplished was to anger visitors to the museum.

Helen: At that point, they realised that if they wanted to draw attention to the inequalities, they really need to adopt a different approach, a different strategy.

Guerrilla Girls: Everyone was willing to excuse the art world, so we decided that day that we had to figure out a way to make people care. The only thing you can do to a system that oppresses you is to make fun of it.

Helen: That was really when the group was born.

Guerrilla Girls: We figured out this formula that if you make people laugh, and if you use information, you can actually change people's minds.

Helen: One of the great things as well about their work is that it was completely data-driven and it was research-based. At the beginning especially, they would conduct weenie counts, which was when you visited a gallery and you would physically count how many men, how many women, how many Asian artists, how many black.

Charlie: I'm sorry, that's called a weenie count.

Speaker: Yes, that's the term.

Charlie: Wow.

Speaker: We can have a whole podcast just about that.

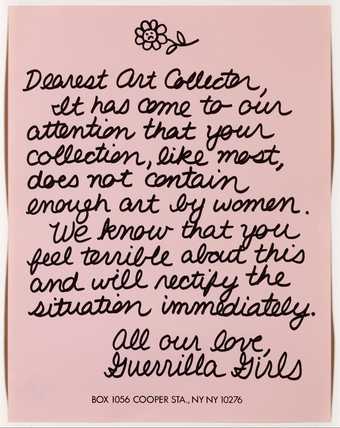

Charlie: Goodness me. Hellen, could you tell us a bit about the peace Dearest Art Collector. Firstly, what it is and what it says?

Helen: Sure. The poster has pink backgrounds, and it's an enlarged handwritten letter. It reads "Dearest, art collector, it has come to our attention that your collection, like most, does not contain enough arts by women. We know that you feel terrible about this and will rectify the situation immediately. All our love, Guerrilla Girls."

Abondance Matanda: Hello. My name is Abondance Matanda.

Charlie: Abundance is an artist and writer who works with archives, museums, and galleries including Tate through poetry commissions, creative research, and community engagement. Her curiosity about inner-city life, youth culture, and empowering women means she loves the Guerrilla Girls.

Abondance: Dearest Art Collector is a handwritten piece of work, and I just love that personal touch. I like the tone of it where it addresses just a generic collector but still looks as if it's quite personal. There's something quite childlike about it.

Charlie: That's what I liked about it. It's almost like as if a little girl had written, "Dear, art collector, why can I not see any women in the gallery." I'm also a big fan of the sad flower at the top. There's just basically a flower with a sad face in it.

Helen: The reason they decided to create this very fluffy aesthetic is that, at the time, after their formation, they were called out, the establishment was suggesting that they were angry, emotional, irrational women, and instead of backing away from that, they leaned into the stereotype. It's dripping in sarcasm. It's all about what's being said between the lines.

Abondance: As a member of the public, you're going to walk into a space and hope to have an intimate connection with the work that you're seeing. Guerrilla Girls are smart because they know that, as a woman, as any kind of minority, you're going to just end up being quite underwhelmed by what you see a lot of the time, and so they have faith that you will come across their work and feel like you're being spoken to.

Charlie: As someone who harnesses humor in your work, could you tell us about the power of humor to make a point?

Abondance: Yes, definitely. Especially as an artist, I feel like people can be intimidated by the word art, and so humor just levels the playing field. It's like I'm very much capable of being on your side, and listening to things, and taking things in from your perspective, which is something I like about Guerrilla Girls. They're very conscious of not wanting to be a part of the system in the market. They know how to use it to their advantage and leverage it.

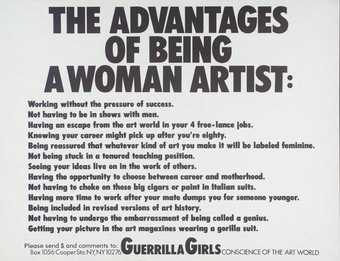

Helen: Another significant piece produced by the Guerrilla Girls is the advantages of being a woman artist. It's a black and white poster and it begins with this very bold headline, THE ADVANTAGES OF BEING A WOMAN ARTIST, and then it follows with 13 ways that women are systematically excluded from exhibitions, literature, textbooks, but one of my favorite points is actually the first one, which reads, "Working without the pressure of success."

Charlie: Something I have done for many, many years.

Helen: Yes, it definitely sets the tone for the rest of the points of the poster.

Abondance: My absolute favorite of the 13 points is "Not having to choke on those big cigars or pain in Italian suits."

Charlie: From a comedic perspective, I think we talk a lot in stand up comedy about imagery and the importance of a really strong image creating a laugh and combinations of words. I think that definitely is one of the ones that is a really humorous highlight. I really like not having to undergo the embarrassment of being called a genius, but that's just because I like really sarcastic things. That's my favorite type of humor. What do you think of the font and the look of it?

Abondance: The way they've signed off on the bottom, I was just comparing it to Dearest Art Collector, and with that, it's just really simple "All our love, Guerrilla Girls." With this one, it's just a lot more formal. They've figured out their little branding thing, they've got their little tag, "We are the conscience of the art world," they've got their address, they want people's money now. It's like they've leveled up. I think that's quite funny about it.

Charlie: Hey there, are you 16 to 25, win £5 tickets to Tate exhibitions, free events, creative opportunities, and special discounts. Join Tate Collective.

[music]

Speaker: The. Art. Of.

Charlie: Marginalized voices sometimes feel pressure to be serious in their art, but for me, it looks like the Guerrilla Girls just wanted to take the piss. It just feels so empowering and bloody hilarious, but like I said at the start, one of the things that I want to know is, is it really okay to laugh in galleries.

James Finch: I'm James Finch, I'm assistant curator for 19th Century British Art and Tate Britain. Because of the prestige which is attached to art galleries and museums, it's easy to go into them and feel like you're walking into a sacred space or something, and that you have this disembodied experience, and you start behaving differently, and you feel really inhibited. I think it's important that people are encouraged not to feel like that and to feel that they can react normally and they can engage with work just in a normal way. A lot of work in art gallery is supposed to be funny, and it would be really sad if people didn't feel that they were legitimized to have that response.

Alice Procter: My name is Alice Procter, I'm a museum educator and writer. I run a project called the Uncomfortable Art Tours, which are guided tours of different national galleries and collections. The easiest thing to forget when you're in an art space is that all of these objects were made to communicate with their original audience, whether that's to be funny, or moving, or sad, or inspirational, or anything like that. We're very used to treating museum spaces like they should be quiet, and reverent, and sacred, but a lot of the work that we're looking at is never intended to be understood in that way. I definitely think you can laugh in art galleries, it's really important to give yourself the freedom to react.

Charlie: Alice, are there funny things that have happened on one of the tours that you've led in galleries?

Alice: Probably the funniest thing that's happened is the number of times I've had people join one of my tours by accident and then end up in completely the wrong place. I've had a couple of people come on tours with me and get about halfway around the gallery before they'll turn to me and say, "This is fascinating, but aren't we supposed to be talking about British modernism? You're spending a lot of time on the 17th century." Honestly, the purest example of humor in a gallery always comes from people noticing something that you've never seen before. I did a tour once where someone wandered off and got lost from the group because they were so entranced by the way that this artist had painted a horse's bum that they stopped paying attention and we left them behind in the wrong gallery. So yes, people are always going to do something weird.

Katy Wan: Yes, it's a tricky one, isn't it? Because I think it might depend on the artist's intentions.

Charlie: That's Katy Wan, an assistant curator at Tate Modern. Yes, I know, another one? It's a big place, isn't it?

Katy: I guess if there were very somber works in the gallery that someone was laughing at, then I might question what exactly was they were laughing at, but gallery spaces are places to come together and to share experiences, so I think humor can be a really good connecting point.

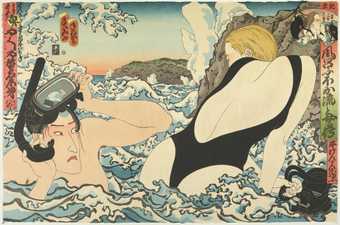

Charlie: I'm speaking with Katy to essentially make me feel clever so I can impress my mates who are into art. She's about to talk me through the artwork View From Here to Eternity by Masami Teraoka, which uses comedy to highlight distinctions between different cultures and eras in art.

Katy: Masami Teraoka is a Japanese-born American artist. He has lived in Hawaii since 1980. He was born in Onomichi in 1936, and his works are, especially his early works, are often satirical and they combine the stylistic influences of Japanese woodblock printing, also known as Ukiyo-e and American pop art. The View From Here to Eternity is a large work on paper. What we see in front of us is two figures emerging from waves crashing onto a rocky coastline. On the left-hand side, we see a man whose face is stylized to look like the Edo era Prince of Samurai and Kabuki actors, except he's removing a plastic snorkeling mask from his face, so that tells us it's more in the present day. You can't help but follow the direction of his eyes which are very firmly planted on the backside of the female figure on the right-hand side. Although you can only see a small part of her face, we can infer from her blond hair that she is of European descent. In the foreground, I don't know if you can see the white surf, kind of like it almost curls around like fingers. Teraoka has spoken about how he very deliberately makes them look like they're caressing, which obviously when you see the waves against the backside of the woman, I think gives it an added sexualized meaning.

Charlie: So it's much kinkier and saucier than we think. Also, I should point out that she's wearing a very stylish swimsuit, one in which I would like to find out where she purchased it, but it's got a big gap in the back. I don't even know how to describe that, Katy. How would you describe the backless bit?

Katy: It's a backless swimsuit.

Charlie: Yes, but it looks like it might join at the top in some stylish European way.

Katy: I love how you're getting fashion inspo from this print?

Charlie: Yes, anything that's set at the beach, I just think what can help me with the social awkwardness of the beach and how horrible I feel being there. Actually, when you look at him, he's got a frowny face, so he's not looking in a way that looks particularly like it's desire. Do you know what I mean?

Katy: Yes, his mouth is down-turned, and I think this points to one of the underlying themes of both this work and Teraoka's whole body of work, which is really to look at this kind of clash of cultures. Obviously, it sets in Hawaii, so if we're constructing a story around this, it might be that this is a Japanese tourist who has come to Hawaii and is just really surprised with what he sees there.

Charlie: It definitely has a feeling of culture looking upon culture. I think that's something that's really clear. I'm really intrigued by what the white European-looking lady is holding in her left hand.

Katy: I believe she's also carrying a snorkeling mask that she has removed. I guess what it suggests is they've come from the point of being in the water and they're coming out of the waves now, and finally, they're able to see each other a little more clearly. I think what's really great about the snorkels and the swimsuit, in fact, is that it really brings it much more into the present day. You wouldn't be mistaken with thinking that this was a print that was made hundreds of years ago. Not only is it a clash between cultures that he's depicting, but perhaps a clash between different moments in time.

Charlie: Up in the top-right corner, there's something else, isn't there? I thought it might be the tentacles of one of those blackfish that are up in the corner. Could you tell us a bit about that?

Katy: At the top-right hand corner, there's a small crescent shape. You have to look really closely, but there's a much smaller figure of a woman. She has two enormous catfish either side of her. Actually, if you look even closer, there is some dialogue within that little bubble, and what it says in kanji scripts, they're saying to her, "Oh, your head is big, isn't it?" and she's exclaiming, "Me?" and then the catfish responds, "It's fine with me."

Charlie: Oh, that's so fascinating. The catfish is having a little chat with her and discussing the size of her head. I wonder what the fish think of the size of their own heads or each other. It's very, very layered. Do you think that the artist's intent in this image was to make people laugh?

Katy: I think knowing what I know Know about his other works, he is an artist who uses humor to bring attention to often really serious social-political issues. A lot of his works have addressed the relationship between US and Japanese culture, and particularly the influence of the US consumer culture in Japan. For example, he has another series called McDonald's Hamburgers Invading Japan, and that was about the first McDonald's store in Tokyo. I think what he's intending to do, in many cases, is use humor to catch people's attention and stimulate debate.

Maybe to have people talking about what's appropriate or not, but I hope it does make people feel a little bit uncomfortable and prompted to laugh a bit because it's ludicrous.

Charlie: Katy, do you remember the first time that you saw this image?

Katy: Yes, I do remember. I was doing research into the collection and particularly trying to understand our representation of artists from the Asia Pacific region. When I came across this, yes, I did a little inward laugh because it's just such a strange and conspicuous image, so unlike many other words that we have in Tate's collection. Yes, I did a little laugh like you know when you're writing a text message and you're lol, but you don't really laugh, you laugh a bit inside. That's what I did.

Charlie: You described it lovely as like an inward laugh. I'm just like have you been to one of my gigs? You sound like an audience member at one of my gigs.

[music]

Speaker: The. Art.Of.

Charlie: Everything I've looked at so far was made in the 20th century, but the origins of comedy as an art form can be traced all the way back to ancient Greece. Humour and irony were used by comic poets and playwrights to influence political opinions. In effect, laughter was weaponized. Our next artist liked to express in some of his drawings his views on alcoholism, sex work, and the impact of people of color on English culture. I'm talking about a Rake's Progress drawn by William Hogarth in 1735. Here again is Alice Procter and James Pinch.

James: There are various strands of humor in the history of art and one of them is caricature and physical exaggerations, which are often very spiteful by the 1400s to 1500s. The idea of physical comedy in depicted form was very common. Hogarth knew about these caricatures by Leonardo and other Italian artists. There's actually a Hogarth picture called Caricatures and Characters, which is very interesting in this sense because he actually copied these heads by Leonardo and others, and besides them, he did his own version as if to say, "These people are just taking the fun out of people by exaggerating their physical features to a ridiculous extent, whereas what I'm doing is extracting some kind of essential character from them." One of the things that I think is really remarkable about Hogarth is that he was able to make paintings which make people laugh out loud. That's one thing that I don't find very often in contemporary art is to find an actual static image which has that kind of effect on you. It's remarkable to think that something like a Rake's Progress, which was painted and then engraved hundreds of years ago still can have that visceral and spontaneous effect on an audience.

Charlie: Alice, could you please tell us a bit about Hogarth's Rake's Progress?

Alice: The Rake's Progress is probably one of Hogarth's most famous series. The main character is a man called Tom Rakewell, and the story is about his collapse into depravity, and debauchery, and things like that. This is the third scene from the series, and it shows Tom in a bar in Central London. It's all about him losing his morals and collapsing into this very weird and decadent way of life. His name is a play on the idea of a rake. The origin of the word rake, meaning someone who's decadent, and chaotic, and doesn't care, and just lives for pleasure is from the word rakehell, like raising hell, and so his name is Rakewell as a way of just really driving home the point. All of the other characters in the scene are part of this narrative. There are little visual signifiers that tell us that some of them are sex workers, some of them are performers, some of them are basically 18th-century strippers. A lot of the women have black stickers on their faces that would be covering the marks of sexually transmitted diseases and that kind of thing. The whole of the scene is set up to be ridiculous and thrilling, but at the same time, giving us a moral message about what's going wrong in Tom's life.

Charlie: Yes, it does look like a pretty wild night out. Is there things coming out of the mouths of these women that are sat around the table? Am I seeing that? What is that?

Alice: One of them is spitting at the other one, and so Hogarth has drawn it like this stream of liquid coming out of her mouth.

Charlie: No way. I was like, "Are they smoking and that's meant to be the smoke?" but that is really gross.

Alice: It's meant to be really gross. Everyone's in various stages of undress, everyone's losing track of what they're doing. The woman who is slightly between the Rake's legs is reaching around behind him and passing a watch, presumably his watch that she's just stolen to her friend, so you get this sense that he's having a great time, but he's also being taken advantage of.

Charlie: Wow. There's a lot of plates in this image as well. There's been so hectic, there's so much going on. Could you tell us a bit more about some of the objects?

Alice: In the background, you've got these portraits around the wall that represent Roman emperors, and generals, and significant figures. All of the good emperors or the ones that are associated with good governance and things like that have their faces ripped out, and the only one who's left is the Emperor Nero who is probably most famous as incredibly corrupt and incredibly decadent as Roman emperors go. Someone is setting a map of the world on fire or trying to, so there's something really unsubtle going on here about the idea that the world is going up in flames, and we're all being corrupted.

It's a way of really driving home this idea that there's nothing good, or wholesome, or clean and healthy about this scene.

Charlie: It's a very surefire way to show your political beliefs. It feels very strong, doesn't it? Is Hogarth religious? He seems like a bit of a prude.

Alice: Hogarth is really tricky in this sense because there's very little that he does approve of. Something that makes him effective as a satirist is the fact that he pretty much hates everybody, so no matter what your background is, he makes fun of rich people, but he also makes fun of the poor and the working classes. He hates the aristocracy, he hates people that are prudish, he hates people that are decadent. He's really, really misanthropic. He also uses the representation of people of color in a lot of his images as a shorthand for the things that he sees was corrupting English society, so there's really vicious racism in some of these images as well. There's a little bit of that in this print of the rights progress. One of the women in the scene is identifiable as black. Her skin tone is much darker than the other characters, and if you follow her eyeline, she's making eye contact with the ballad singer that's just come in on the righthand side of the image. The singer is holding a broadsheet ballad which is like a popular song sheets and it's called the Black Joke. The Black Joke was a ballad that was a sexual pun, it's a grotesque and really rivaled song about vaginas, and the idea of women as laughing at men and dangerous. It's all very paranoid sexuality kind of stuff, but it's also got this racist undertone and frankly, overtone to it as well.

Charlie: At first, I thought it was just grumpy, but it turns out he's significantly more problematic and layered than that. Anything from you, James?

James: Yes, I completely agree with everything that Alice has said. In relation to humor in art generally, what we think of when we think of humour in art is its context, and its culture-specific, and so I think the more that we can expand that through having access to work produced by different communities, then the better and the richer our sense of this subject will be.

[music]

Charlie: By making this podcast, I've discovered that art incorporates humour in various ways from a literal joke, a parody, a ridiculous image to something scandalous or absurd. One of the big things we talk about in stand up comedy is that fine line, that tension that creates the release of laughter, and the root is often the things that are difficult to talk about in society. I guess that's one of the brilliant uses of humor, it allows us that space and opportunity to say, "Oh yes, I hadn't thought about it like that." So next time you feel like laughing in a gallery, it's not because you're a bit awkward, it's because you get it. That's my story anyway and I'm sticking to it.

You've been listening to Tate's Podcast the Art Of with me, Charlie George. If you've enjoyed this episode, please rate, review, and subscribe wherever you get your podcasts or check out previous episodes from the series which explores the art of failure, dreaming, and even love. To find out more about the artworks we've discussed, visit Tate's website.

Massive thanks to all our contributors. The Art of comedy was produced, edited, and mixed by Phil Brown with research by Deborah Shorinde. The executive producer with Chrystal Genesis and it was a Stance Media production for Tate.

Speaker: The. Art. Of.

[00:35:03] [END OF AUDIO]