Typeface by Aurélie Garnier

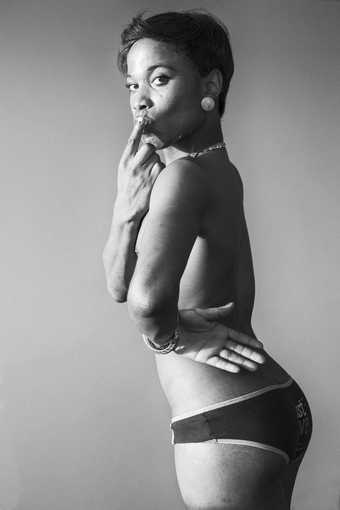

Zanele Muholi is rewriting visual history and challenging the way we think about art. The Black, queer, non-binary activist (who uses the pronouns they/them/their) documents the disconnect at the heart of South African society – where marginalised communities face violence, prejudice and bigotry despite the country’s liberal reputation.

Their work is bold and confrontational but also tender, beautiful and loving, from self-portraits that explore themes of Blackness and selfhood, to intimate photographs of LGBTQIA+ people of colour.

Tate curator Kerryn Greenberg explains how and why Muholi’s work is so significant.

For the Yes, but why? article series we teamed up with WePresent to tell the stories of Muholi and four other game-changing artists. Here we chose three quotes from the article to give you some insight into their world.

Zanele Muholi

Bester I, Mayotte 2015

© Stevenson Gallery

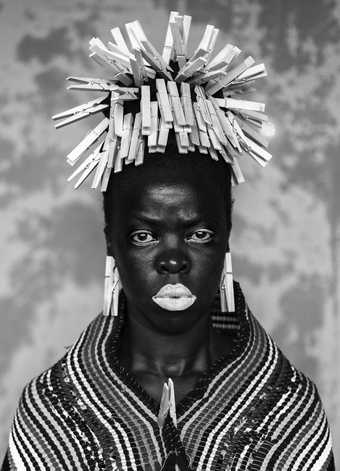

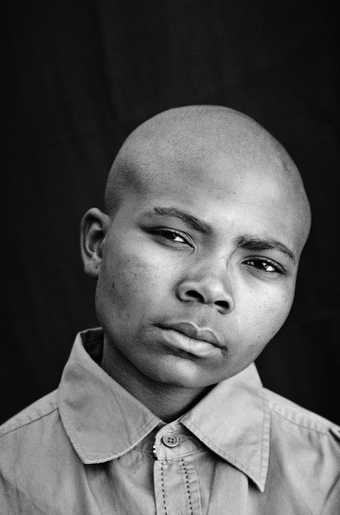

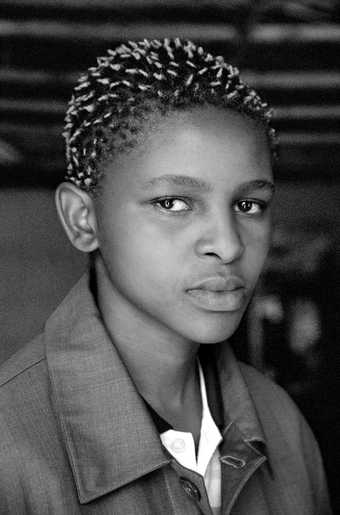

1. Their work paints a new picture of lesbian, trans and gender non-conforming identities

Zanele Muholi

Nosipho Solundwana, Parktown, Johannesburg 2007

© Stevenson Gallery

Zanele Muholi

Manucha, Muizenberg, Cape Town, 2010

© Stevenson Gallery

Zanele Muholi

Nokuthula Dhladhla, Berea, Johannesburg 2010

© Stevenson Gallery

Zanele Muholi

Zukiswa Gaca Makhaza, Khayelitsha, Cape Town 2010

© Stevenson Gallery

Faces and Phases is an ongoing series whereby the artist was seeking to document and photograph Black lesbians, trans men and gender non-conforming individuals. There's now a mass of these incredibly beautiful portraits, which generally are presented in a grid, to show that, actually [...] giving visibility to these people is a life's work. There are many portraits of the same individuals over the course of a number of years. So you can see how people age, how they transition, sometimes, and how the way they present themselves, alters.

It is about acknowledging pain and trauma, and trying to heal people, and heal oneself through those images. Images that Muholi wants their community, to be proud of, and feel well represented by.

Kerryn Greenberg

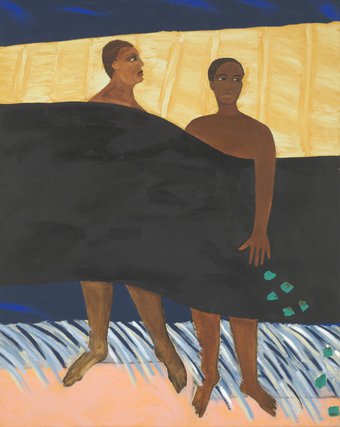

2. They create powerful self-portraits shot around the world

Zanele Muholi

Somnyama Ngonyama II, Oslo 2015

© Stevenson Gallery

As Muholi's career started to take off internationally, they were traveling a huge amount in hotel rooms. They were exposed to the usual hassles of border immigration and airports, where racial profiling is still a reality, and entering spaces that are historically white. [They were] very conscious of the feeling that perhaps they were not quite wanted there, despite having been invited.

In 2012, they began to make a series of self-portraits, which actually I think are more accurately presented as self-projections, rather than self-portraits. In them, there is this sense of unapologetic selfhood. The sense that actually, you can be Black, you can encompass many histories, and projecting that in a really powerful way.

These photographs are often taken in situations, as I said, away from home, where Muholi might not have access to the same camera each time. And the light conditions are very variable. So, you'll see that when they're printed, they're at very different scales, and that is representative of the fact that they've been made on the hop.

The itineracy of the lifestyle is very much evident in the pictures themselves, but also in the titles. They're often titled in isiZulu, the artist's home language. But then there will be the place in which they've been made, and that could be New York, that could be Norway, you know, a whole range of different locations.Kerryn Greenberg

Zanele Muholi

Bona, Charlottesville 2015

© Stevenson Gallery

Zanele Muholi

Bester VIII, Philadelphia 2018

© Stevenson Gallery

3. Their practice is about inner and outer beauty

What I really want to talk about is beauty. Because I think for Muholi, that's kind of where it all stems from, is recognizing beauty in things that you might not expect. Muholi has said "All I want to see is beauty. And that doesn't mean you have to smile, or try harder. Just be."

I think that's very much linked to the history of Apartheid, of course [...] As a Black person being told constantly 'your hair isn't straight enough', 'you should look like this', 'you should look like that' and that being legislated under Apartheid. But it's also what is in the magazines, this idea of the perfect beauty. Muholi's counteracting them, saying actually, none of that is relevant. It's about being the beauty that you want to be.

There's a really great series called Brave Beauties, which [...] pictures trans women and gender non-binary individuals, many of whom have been in beauty pageants, occupying space. Demanding attention. And being absolutely stunningly beautiful. And you kind think, 'yeah, what are our notions of beauty, what are these kind of constructions that are absolutely false?'

Kerryn Greenberg

Zanele Muholi

Eva Mofokeng I, Parktown, Johannesburg 2014

© Stevenson Gallery

This is based on an interview between Maisie Skidmore and Tate curator, Kerryn Greenberg for story-telling site WePresent.