Tseng Kwong Chi

London, England (Tower Bridge)

(1983)

Tate

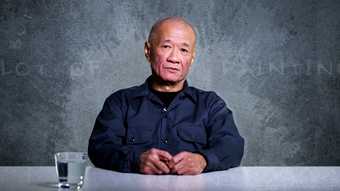

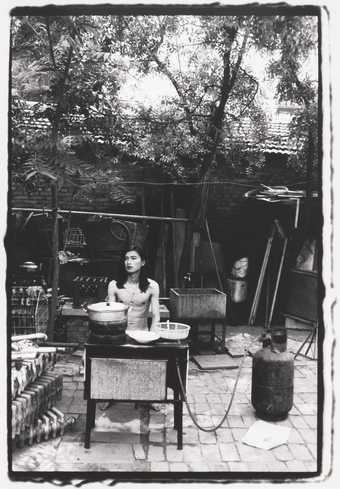

Ma Liuming

Fen Ma Liuming

(1993)

Tate

A Tale of Two East Villages

The “East Village” scene was that fleeting yet iconic moment in 20th century global art history when a generation of misfits, immigrants, aesthetes, dreamers and rebels came together in the East Village of Manhattan, New York, at the end of the ‘70s, in a creative outburst that had lasting effects on subsequent art milieux and soundscapes. The first publication of the East Village Eye, in May 1979, marked the unofficial beginning of the era. This scene was, however, declared dead in the same publication only a few years later, in 1985, by one of its chief spokespeople, Carlo McCormick, . By January 1990 the East Village subsection had been completely dropped from the Gallery Guide, announcing its demise.

Shortly thereafter, curiously enough, another East Village sprang up 6,000 miles away in Beijing, China. From 1993 to 1997 a group of artists (including Ma Liuming, Zhang Huan, Rong Rong, Cang Xin, Duan Yingmei, Zuoxiao Zuzhou, among others) living in Dashanzhuang, a village in Dongfeng County, enacted a series of provocative artistic experiments—as individuals and as a collective—that put Chinese performance art on the world map. Their subversive use of embodied performance, in opposition to the art forms officially supported by the Chinese State on the one hand, in contrast to emerging painting styles like cynical realism on the other, resonated with the anti-authoritarian spirit the similarly fleeting New York East Village scene had itself drawn from the counter-culture movement of the United States.

That the two scenes shared the same name was not entirely coincidence. The Beijing artists had renamed their residence the “East Village,” in part to forge a distinct identity with regard to the Yuanmingyuan art village, commonly referred to as the West Village due to its location on the west side of Beijing, and arguably the epicenter of contemporary art at the time.[1] After consulting with art historian and critic Li Xianting, the East Villagers added “Beijing” as a prefix to differentiate themselves from the New York scene of the preceding decade. Underlying this moniker was nevertheless a sly homage to their New York near-namesake, which the Beijing artists had received occasional news of in limited media publications (such as a one-page feature in an 1986 issue of Fine Arts in China) and from the mouths of Chinese émigré artists and diplomats who traveled to Beijing from New York in the early 1990s, including Ai Weiwei. Notably, the work of Tehching Hsieh was cited as an influence by East Village artist Cang Xin, who even made an unrealized proposal to pick and burn trash found in the village for a whole year, à la Hsieh.[2]

Despite Cang’s homage, and despite naming themselves after the New York East Village, the Beijing collective did not straightforwardly imitate their counterparts’ tactics or practices. As Ma recalls, “We only vaguely heard about the New York East Village being a meeting point of vanguardist artists, but didn’t really know much about the scene.”[3] For that matter, he also reveals, he had not, at the time he began working in his signature style, “... seen any live performance of Western artists. Occasionally I saw some documents of [Western] performance art in books, but since I couldn't read English I couldn’t really grasp the context … What they gave me was a certain impression, not anything concrete.”[4] Propelled by a vague, vanguardist impression, the consequent evolution of the Beijing East Village, most notably in the realm of performance, could be seen as a kind of indigenized artistic expressions responding to the specific sociopolitical contexts of China in the early 1990s. To tell the tale of these two East Villages, therefore, we would do better to look less at the factual correspondences than at the astounding artistic resonances manifest between them.[5]

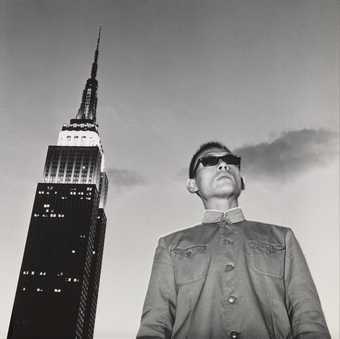

Tseng Kwong Chi’s “Ambiguous Ambassador”

One exceptional resonance between the two East Villages is evinced in the work of two performance artists, Tseng Kwong Chi (1950–1990) and Ma Liuming (1969–), who worked roughly a decade apart. Tseng, who had passed away by the time Ma moved to Beijing’s East Village in 1992, was never aware of Ma’s existence at all. And while a number of Chinese artists have cited Tseng as an influence (Zhang Huan, for instance, another Beijing East Village artist and Ma’s close collaborator in the early years, came across Tseng’s work at the teacher’s library of Beijing’s Central Academy of Fine Arts in 1993, before the East Village scene took off), Ma was not exposed to Tseng’s work until years after developing the alter-ego Fen Maliuming.[6] Despite this lack of direct connection, and sharing ostensibly nothing in common other than their Chinese heritage, the two artists independently arrived at drag as their medium, and used it, each in their idiosyncratic way, to negotiate the power of performance and representation.

The Gang's All Here, New York, 1983. Photograph: Tseng Kwong Chi © Muna Tseng Dance Projects, Inc.

(Standing, from L): Katy K, Keith Haring, Carmel Johnson, John Sex, Bruno Schmidt, Samantha McEwen, Juan Dubose, Dan Friedman.

(Kneeling, from L): Kenny Scharf, Tereza Scharf, Min Thometz/Sanchez, and Tseng Kwong Chi.

Born Joseph Tseng in Hong Kong in 1950, the artist later known as Kwong Chi moved with his family to Vancouver in the 1960s. After studying at the University of British Columbia, then at the École supérieure d’arts graphiques in Paris, Tseng followed his sister Muna to New York in 1978, where he settled down in the East Village. A fixture of the 1980s Mudd Club and Club 57 set, along with artists such as Ann Magnuson, Kenny Scharf, and Jean-Michel Basquiat, Tseng was for a long time dismissed as “a footnote to Keith Haring”[7] (his best friend), and is today best remembered as a photographer, especially of New York’s downtown scene during the 1980s. However, as Tseng himself emphasized, his work could also be approached through the lens of performance, with photography simply being the means of documentation. To conceive of Tseng as a performance artist sets the stage for a comparative analysis of his and Ma’s endeavors.

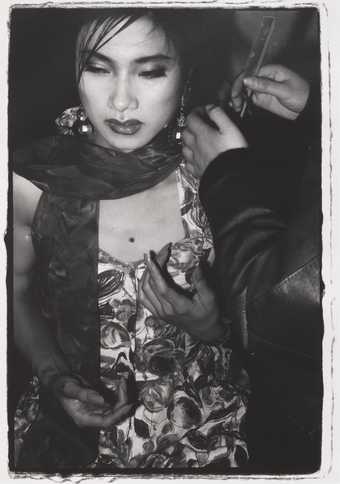

Tseng Kwong Chi

New York, New York (Empire State)

(1979, printed 2018)

Tate

In his iconic 1979–1989 “Expeditionary Self-Portrait Series” (otherwise known as the “East Meets West” series), Tseng, who was openly gay, posed in front of iconic sites across the world wearing his signature Mao suit.[8] In the 1979 work New York, New York (Empire State), one of the earliest works in the series, the artist is seen in the foreground wearing a pair of Ray-Bans, with the Empire State Building behind him to his left. Existing scholarship has praised the artist’s juxtaposition of symbolic Chineseness (the Mao suit) and signs of Western empire (the skyscraper) as either subverting a “long history of Orientalist painting and photography” or embodying the “quintessential outsider.”[9] At a moment just a few years after the Cultural Revolution in China, when entry to the US from China was still mostly reserved for party members, and with the specter of the post-WWII Red Scare still lingering, Tseng’s performance of Chineseness ingeniously embodied what was to the American audience of his day an almost non-human Other, inciting at once curiosity and awe, highlighting such stereotypical dichotomies as East and West, us and other.

However, existing readings have downplayed what art historian Joshua Chambers-Letson aptly describes as an underlying “queer scene of performance”—inextricably tied to Tseng’s intersectional identity as not only a racial “other,” but also a sexual minority. As noted in various accounts, Tseng in person was quite a flamboyant character; openly gay, his everyday gender performance was markedly different from the figure of the “ambiguous ambassador” he portrayed in the “East Meets West” series. Following Chambers-Letson, we may begin to catch sight of that queer scene by reading Tseng’s performance through the lens of drag.[10] While this term was, for a long time, used to refer rather squarely to the exaggerated imitation of the opposite gender by a cisgender performer, with drag queens—gay men performing femininity in a hyperbolic fashion—being the most visible example, recent developments in gender and performance studies have repudiated this narrow definition of drag. The collapse of the gender binary means that there is simply no such thing as “the opposite gender”—rather, there are a multitude of gender roles. Another useful reference is Paris is Burning (1991), Jennie Livingston’s now legendary documentary about 1980s New York ballroom culture (which featured many transgender drag performers). The wide varieties of drag captured in Paris is Burning far transcend the limited category of gender imitation, and propose drag as encompassing almost any kind of hyperbolic performance of passing as someone else, whether in terms of sex, class, or style.[11]

In this light, Tseng’s “ambiguous ambassador” is a drag persona insofar as it is an exaggerated performance of a role different on multiple levels from Tseng’s everyday self. In many works from the “East Meets West” series, such as New York, New York (Empire State) 1979, Tseng appears—eyes and emotions hidden behind a pair of sunglasses—sturdy and virile, wearing a kind of masculine drag that exudes power, even malice. Meanwhile, in other works such as the same year’s New York, New York (Brooklyn Bridge), Tseng jumps to reach the frame of the photo, mid-air against the backdrop of the East River, revealing in his flamboyant posture a return to his usual gender performance. The revelation of his flamboyance counters the mask of masculinity put on elsewhere. Does the ambiguity of the globe-trotting ambassador originate from some dark secret, such as closeted homosexuality? Or are his layers of otherness so entangled that it’s impossible to see only just one aspect without simultaneously registering the others—foreign, communist, queer? In other words, the exact terms of the ambassador’s otherness remain perpetually unfixed, turning the body into a mirror reflecting the general public’s polyvalent fear. And while Tseng’s masculine drag effectively counters the desexualization and effeminization of the Asian male body in American culture, its insistent artificiality (so casually revealed as such by that flamboyant jump) in turn questions the power and mobility prescribed by a heteronormative society to a masculinity with which Tseng himself, a minority queer subject, did not identify. One might usefully view Tseng’s drag through the lens of what the late queer scholar José Esteban Muñoz would call dis-identificatory performance, a successful recycling of a mainstream caricature into “powerful and seductive sites of self-creation.”[12]

Fen-Ma Liuming: Ma Liuming’s Androgynous Drag

In September 1993, three years after Tseng had passed away in a hospital in Toronto, an androgynous youth approached the gay artist duo Gilbert & George at the opening of their solo exhibition at the China Museum of Art, Beijing. He introduced himself as a performance artist and invited them to visit his studio, somewhere he called the East Village. The next day, when Gilbert & George arrived at what turned out to be a studio-cum-apartment in a dilapidated village covered in mud, sewage, and trash, Ma Liuming put on a cassette of Pink Floyd’s The Wall, took off his shirt, and climbed onto the table in the middle of the room. As he raised his fingers to touch a crack in the ceiling, blood-like liquid started dripping down over his arms and body. Coming down from the table, Ma reeled as if about to faint, until he was caught by the arms of fellow artist Zhang Huan. Titled Dialogue with Gilbert & George, this was the earliest performance to take place in the Beijing East Village, and anticipated the birth of Ma’s androgynous alter-ego Fen-Ma Liuming. From then on Ma continued to perform in character for over a decade, until he officially quit performance art in 2004.

Ma Liuming

Fen Ma Liuming

(1993)

Tate

A quick glance at Ma’s work may give the impression of drag as conventionally understood, namely, a cis-male’s performance of femininity. In Fen-Ma Liuming (1993), one of his earliest documented performances, Ma is seen in a floral print dress and a silk scarf, his long fingers making a feminine gesture. Wearing heavy eyeshadow and a pair of luminous earrings, Ma looks demurely away from the camera while a person fixes his hair. To a Western audience familiar with queer visual culture the image might just suggest backstage photography at a drag show. However, Ma’s early drag performance is not geared towards gender affirmation, but rather aims at social critique. As the artist wrote in the 1994 Black Cover Book published by Ai Weiwei, “The idea of ‘in-between sex’ is meant to expose a rather awkward reality: we begin to judge a person’s cultural identity based on their clothes, rather than their characters. Our attitudes toward matter prefigure our spiritual attitude.”[13] Judging by this early statement, Ma’s early performance of drag was more, if anything, an ambivalent commentary on the rise of materialism and consumerism in early 1990s China.

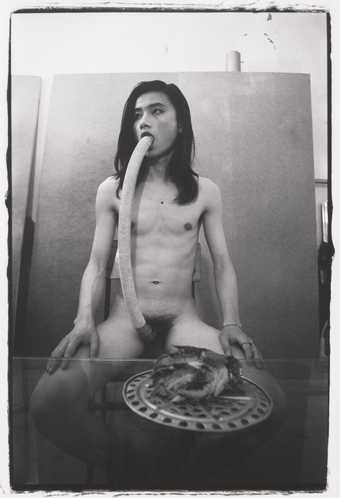

It is worth noting that Ma is a heterosexual cis male, which he has always been open about. Contrary to many existing readings of the work as one of the first instances of transgender performance in China, it is important to clarify his performance not as a case of queer representation, but as an appropriation of it. However, this appropriative aspect of Ma’s performance does not detract from its originality and power. At the time when Ma was developing his performance character, he was not yet aware of the tropes of drag à la Marcel Duchamp and Andy Warhol in Western art history, let alone the history of drag among queer and trans performers in nightlife scenes.[14] And indeed, without any previous exposure to gender and queer theory (phenomena largely limited, in the 1990s, to North American academies), the artist’s observation of the societal transformations around him resulted in a remarkably idiosyncratic use of drag. After the initial experimentation with dressing up, Ma quickly switched to performing naked, his exposed genitals contrasting his effeminate face adorned with makeup—in defiance of government prohibition of public nudity, and a long tradition of sexual repression that was only beginning to set loose in China in the early 1990s. The decision to perform nude reveals his intention is not at all to pass as a woman, but something more transgressive: to project an outlawed body that trespasses the norms of gender and public decency. From dressed to naked, and from ambivalence to revelation, the transformation of Ma’s drag persona reveals a personal discovery of the transgressive power of gender performance.

Ma Liuming

Fen Ma Liuming’s Lunch II

(1994)

Tate

Ma Liuming

Fen Ma Liuming’s Lunch I

(1994)

Tate

From the initial encounter with Gilbert & George that triggered the debut of Fen-Ma Liuming to the ensuing evolution of the character, Ma’s artistic awakening coincided with the dawn of Beijing’s rise to global contemporaneity in the early 1990s. Having had limited exposure to Western art, Ma proved better able to hone an individual style of drag as the performance of dissidence and taboo. Borrowing from Chinese philosophy and personal observation, Ma’s performance remains an exceptional case in contemporary Chinese art, reflecting a local negotiation of individual body and social norms in one of China’s most sweeping transitional periods.

Working in different cultural contexts, Tseng Kwong Chi and Ma Liuming both turned to drag as their medium, and used the practice to question norms while embracing alterity. Uniting their approaches is a kind of minoritarian counterposition—in Tseng’s case, that of a racial and sexual minority in the Reagan-era US; in Ma’s, that of a rebel artist outside the official system, determined to discover his artistic and personal identity through an art form at the time very much on the margins. The characters of their work, similar and dissimilar, mirror the relationship between the two East Villages from which they emerged. Sharing name and spirit, and both equally transient, the resonances between these two scenes continue to reverberate through the conscience of a global art history and a transnational, Sinophone art community that look beyond the binaries of West and East, center and periphery, original and imitation.

Alvin Li 李佳桓 is the Adjunct Curator, Greater China, Supported by the Robert H. N. Ho Family Foundation, at Tate.

Research supported by Hyundai Tate Research Centre: Transnational in partnership with Hyundai Motor

The author would like to thank David Xu Borgonjon, Zoe Meng Jiang and Peng Zuqiang for their thoughtful feedback.

Footnotes

[1] Through interview with the artist, April 2021.

[2] Duan Jun, Beijing East Village Performance Art of the 1990s, Hong Kong Four Seasons Press: Hong Kong, 2016.

[3] Email exchange with the artist, March 2022.

[4] Email exchange with the artist, March 2022.

[5] Fore more on “connections” and “resonances” as two methodological tools to seek out contact points in global art history, please see Reiko Tomii’s Radicalism in the Wilderness: International Contemporaneity and 1960s Art in Japan, MIT Press: Cambridge Massachusetts, 2018

[6] Regarding Tseng Kwong Chi’s influence on Zhang Huan, see Alexandra Chang, “Epic Journey: Tseng Kwong Chi in the Diaspora,” Tseng Kwong Chi: Performing for the Camera. Ma’s introduction to Tseng was explained in an email exchange with the artist in March 2022.

[7] Muna Tseng and Ping Chong, “SlutForArt.” PAJ: A Journal of Performance and Art 22, no.1 (2000): 111-28.

[8] The idea for this alter-ego was born after a family brunch at a high-end New York restaurant. In keeping with the restaurant’s dress code, Tseng arrived in a Mao suit—the only suit he owned at the time, which he bought in a thrift store in Montreal, as it was difficult to find in the United States—and, to his amusement, was treated by the waiters as “a Chinese dignitary, a VIP.” See “Remembering SlutForArt: Tseng Kwong Chi. A Conversation on Dance, Performance, and Art with Muna Tseng, Ping Chong, Bill T. Jones, and scholar Karen Shimakawa,” Asian Diasporic Visual Cultures and the Americas 1(2015) 311-324

[9] Margo Machida, “Out of Asia: Negotiating Asian Identities in America.” In Asia/America: Identities in Contemporary Asian American Art, edited by Margo Machida, Vishakha Desai, and John Tchen, 65–99. New York: Asia Society Galleries and the New Press, 1994.

[10] The drag element in Tseng’s work has only been mentioned in passing by periodicals, such as in John Philip Habib’s “A Life in Chinese Drag,” published in a 1984 issue of Advocate (which itself was quoting Bill T. Jones), but never to my knowledge analyzed in depth. John Philip Habib, “A Life in Chinese Drag,” Advocate: The National Gay and Lesbian Newsmagazine, April 2, 2002, 72.

[11] For more on the notion of ‘passing’ and its resonance with strategies employed by artists interested in pop, please see Catherine Wood, “Capitalist Realness,” Pop Life: Art in a Material World, edited by Jack Bankowsky, Alison M. Gingeras and Catherine Wood, Tate Publishing 2009.

[12] See José Esteban Muñoz, Disidentifications: Queers of Color and the Performance of Politics (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999).

[13] Quoted in Duan Jun, Beijing East Village Performance Art of the 1990s, Hong Kong Four Seasons Press: Hong Kong, 2016. Translation by the author.

[14] Email exchange with artist, March 2022.