In Tate Modern

Media Networks

Free- Artist

- Tseng Kwong Chi 1950 – 1990

- Medium

- Photograph, gelatin silver print on paper

- Dimensions

- Image: 900 × 900 mm

- Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Presented by the artist’s estate 2019

- Reference

- P14982

Summary

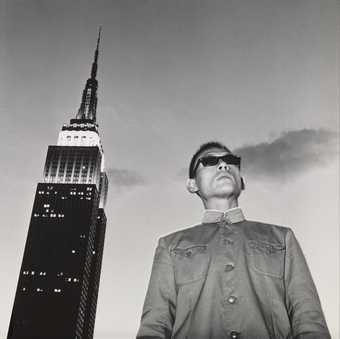

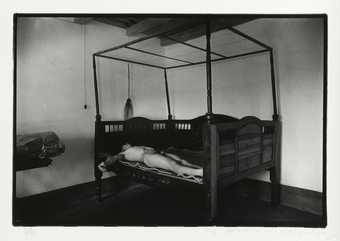

This black and white silver gelatin black and white photograph is part of a larger body of work by the Hong Kong-born American photographer Tseng Kwong Chi known as the East Meets West series or the Expeditionary Portrait Series. This series, which Tseng began in the late 1970s and continued into the 1980s, is his best-known work (see also New York, New York (Empire State) 1979, printed 2018, Tate P82466; and San Francisco, California (Trans Am) 1979, printed 2008, Tate P82467). The artist photographed himself in front of popular tourist sites, both in the United States and elsewhere. He is rigidly positioned, wearing a Zhonghan or ‘Mao suit’ and a deadpan expression. Co-opting the identity of a Chinese government official or dignitary, Tseng shot these images himself, setting up his camera, situating himself within the composition and clicking the shutter release cable, which is often visible in his hand. About his intention in making the works, he stated: ‘My mirrored glasses give the picture a neutral impact and a surrealistic quality I’m looking for. I am an inquisitive traveller, a witness of my time, and an ambiguous ambassador … My photographs are social studies and social comments on Western society and its relationship with the East. [I pose] as a Chinese tourist in front of monuments of Europe, America and elsewhere.’ (Quoted on artist’s website, http://www.tsengkwongchi.com/, accessed 20 May 2018.)

Part clichéd tourist shot, part conceptual performance (long before the advent of selfies), Tseng began this series in New York City, taking self-portraits and performing for the camera against the backdrop of the Brooklyn Bridge, Statue of Liberty and Empire State Building. He then travelled across the United States to San Francisco, Disneyland and the Grand Canyon, and later to Europe where he visited London, Paris and Rome. Made at a time when concerns around identity politics were brewing and the cultural wars in America pitched ethical and moral values into representations of race and sexuality within contemporary art, Tseng’s images subversively explore notions of cultural identity. Using his own body and adopting a look of ‘Chinese-ness’ through the wearing of the Mao suit, his images reveal the perceived and at times stereotypical dichotomies between difference – between the West and East, the mainstream and marginal.

Though born in Hong Kong to Chinese nationalist parents who fled the Chinese mainland following the Communist victory in 1949, Tseng spent much of his adult life in New York, where he became a key figure of the downtown art scene in the 1980s. Part of an intimate circle of artists that included Keith Haring (1958–1990), Kenny Scharf (born 1958) and Cindy Sherman (born 1954), Tseng developed a career around his performative self-portraits, as well as documenting the art scene and nightlife of downtown New York. He was known as the close friend and loyal documenter for Keith Haring, producing over 25,000 images of Haring’s ephemeral drawings in New York subways, as well as of Haring’s other work. Tseng died of AIDS-related causes at the age of thirty-nine.

Seen within the context of works by his contemporaries such as Cindy Sherman and Yasumasa Morimura (born 1951), Tseng’s self-portraits are provocative conceptual tools for imagining or fashioning the other – whether cultural, political or sexual – that still resonate today. Speaking of the social relevance of Tseng’s images, the American curator Dan Cameron has written:

The personage he was automatically taken to be while wearing the uniform of the Chinese Revolution invariably transformed every social occasion into a seriocomic ritual of cultural diplomacy. Tseng was not simply a visitor from faraway China – he was the embodiment of a cultural difference that permeated all aspects of his being. At a historical moment when identity politics and contemporary art were still taking each other’s measure, Tseng’s photographic alter-ego became the quintessential outsider, for whom nothing can be assumed and everything must be explained … One of the central underpinnings of Tseng’s work is the Warholian conviction, shared with his better-known friends and contemporaries, that the artist is obliged to create more than the art itself – he must also clearly occupy a nexus of historical, critical, and ethical associations that provide the viewer with a contextual framework through which the art can be deployed to interpret the world around it.

(Dan Cameron, in Paul Kasmin Gallery 2008, unpaginated.)

The photographs in Tate’s collection are posthumous prints produced by the artist’s estate in editions of nine with two artist’s proofs. New York, New York [Empire State] 1979, printed 2018 is number eight in its edition; San Francisco, California (Trans Am) 1979, printed 2008 number two in its edition; and London, England (Tower Bridge) 1983, printed 2018 is number four in its edition

Further reading

Margo Machida (ed.), Asia/America: Identities in Contemporary Asian American Art, exhibition catalogue, The Asia Society Galleries, New York 1994.

Kenny Scharf, Lily Wei, Dan Cameron and Muna Tseng, Tseng Kwong Chi: Self-Portraits 1979–1989, exhibition catalogue, Paul Kasmin Gallery, New York 2008.

Amy Brandt (ed.), Tseng Kwong Chi: Performing for the Camera, exhibition catalogue, Chrysler Museum of Art, Norfolk, VA and Grey Art Gallery at New York University 2015.

Clara Kim

May 2018

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Display caption

Tseng Kwong Chi’s work explores cultural difference and belonging. He uses re-enactment to confront and subvert societal constructions of race and identity. Tseng used a large-format camera and shutter release cable to stage self-portraits at tourist sites in the US and Europe. He wore a ‘Zhongshan suit’ or ‘Mao suit’ (a tunic-style suit with a flipped collar) to adopt the identity of a Chinese government official. Tseng’s performance reveals the prejudice of observers, who may assume he is a communist foreign dignitary visiting a famous Western landmark. This portrayal contrasts with Tseng’s identity as an artist living and working in New York.

Gallery label, November 2022

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

You might like

-

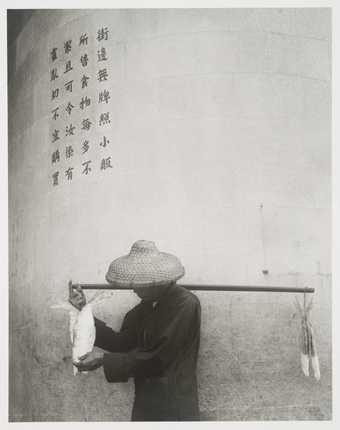

Yau Leung Salt Fish and Government Warning

1966 -

Yau Leung Wong Tai Sin Resettlement Estate

1965 -

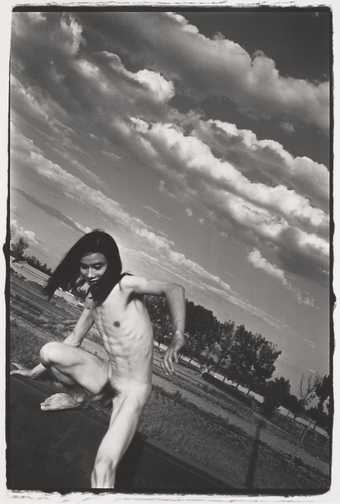

Ma Liuming Fen Ma Liuming

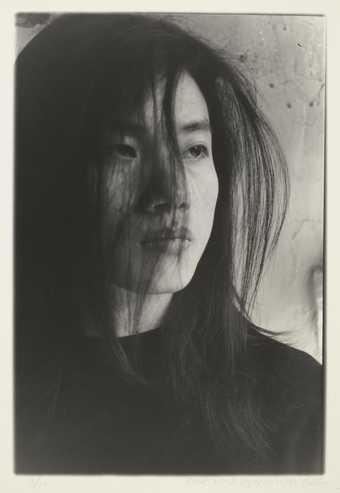

1993 -

Ma Liuming Fen Ma Liuming’s Lunch I

1994 -

Ma Liuming Fen Ma Liuming’s Lunch II

1994 -

Tseng Kwong Chi New York, New York (Empire State)

1979, printed 2018 -

Tseng Kwong Chi San Francisco, California (Trans Am)

1979, printed 2008 -

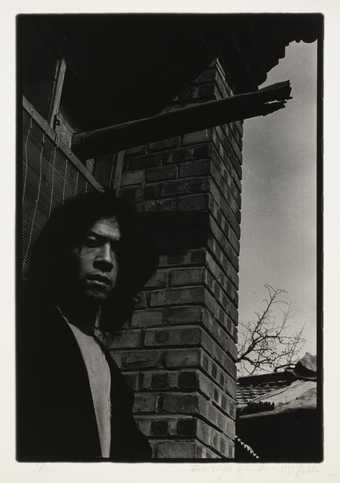

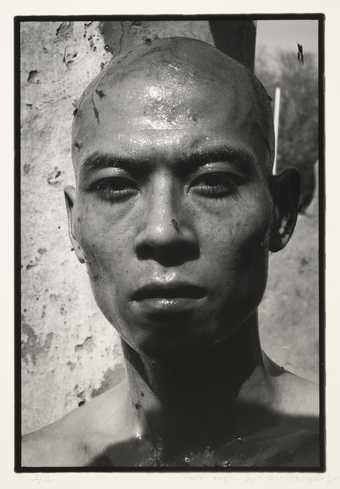

RongRong 1993 No. 10 (Zhang Huan)

1993 -

RongRong 1993 No. 25 (Ma Liuming)

1993 -

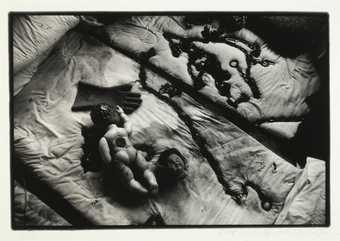

RongRong 1994 No. 1

1994 -

RongRong 1994 No. 15 (Zhang Huan, ‘12 Square Metres’)

1994 -

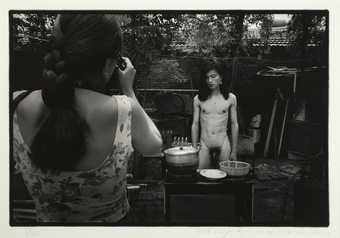

RongRong 1994 No. 46 (Ma Liuming, ‘Fen-Ma Liuming’s Lunch’)

1994 -

RongRong 1994 No. 80 (Zhu Ming)

1994 -

RongRong 1994 No. 89

1994 -

RongRong 1994 No. 1 (Self-Portrait, Fujian)

1994