Farid Belkahia in his studio in Marrakech, 2010

© Fondation Farid Belkahia

Farid Belkahia (1934–2014) was born into a wealthy bourgeois family in Marrakech. He grew up with his father’s art collection, and his further artistic awakening would take place within his father’s circle of friends, a group that included painters such as the Polish Olek Teslar and the French Jeannine Guillou. Through Guillou he met Nicolas de Staël, the French painter of Russian origin, during his stay in Morocco in 1937.

From about 1950, Belkahia took classes in Teslar’s studio, also attended by the Moroccan painter Moulay Ahmed Drissi. During these years, and prior to his departure from Morocco, Belkahia distanced himself from the Orientalist styles that persisted through the academic art teaching and Salons under the French Protectorate (1912–1956), instead choosing his own path. His first politically inspired works – La veuve et les enfants and Mohamed V dans la lune 1954 – denounced the forced exile of King Mohammed V by the colonial administration.

From the second half of the 1950s, and during the 1960s, Belkahia travelled all over Europe, the Maghreb and the Middle East in search of his cultural roots, constantly shifting his glance from one civilisation to another. Two periods during this time were most influential to his work. The first was his stay in Paris between 1955 and 1959, where he studied at the School of Fine Arts. Here, he consolidated his understanding of modern European art (from Georges Rouault to Wassily Kandinsky and Paul Klee) and developed his particular approach to light and colour – especially while in the studio of Raymond Legueult.

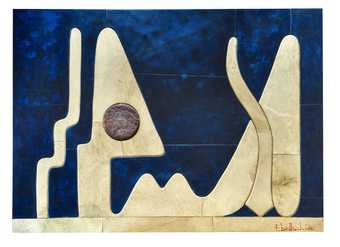

Farid Belkahia

Tortures

(1961–1962)

Tate

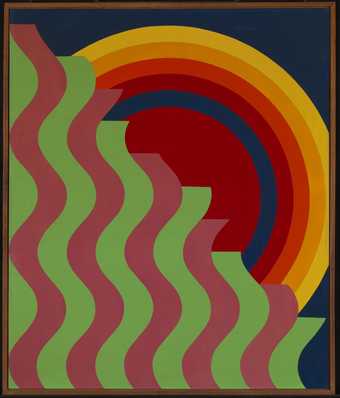

The second significant period for Belkahia was in Prague from 1959 to 1962, where he learnt scenography at the Theatre Academy. Although he became acquainted with communist circles, which included the writers Louis Aragon, Elsa Triolet and Pablo Neruda, he never subscribed to their doctrine. In fact, Belkahia held throughout his life to his posture of a distanced observer who wrestled with the contemporary world and its political upheavals, but one who, nevertheless, refused ideological confinement. During those Prague years, he produced a set of expressionist works that referenced the political situation in Algeria (the Algerian War of Independence, 1954–1962), the most eloquent of which – Tortures 1961–2 – testifies to war’s spiral of death and the dehumanizing practices it condones. The viewer is faced in these works with the painful stiffening of disarticulated bodies that are treated as hollow geometric shapes, angular contours encircled in black, forms frozen in anguish and inflicted violence that the warm chromatic palette cannot silence. In the midst of the Cold War, in the aftermath of the Bay of Pigs crisis, Belkahia expressed his support for Cuba’s revolutionary cause with his painting Cuba Si 1961, in line with his commitment to universal human values.

Farid Belkahia

Cuba Si

(1961)

Tate

Belkahia returned to Morocco in 1962, six years after the country’s liberation from French rule. He was determined to take an uncompromising artistic stand, embodied, as early as 1963, by his imperative need to compete against Western influence with the definition of a specifically Moroccan modernity. The result was his radical and definitive break with easel painting and the oil painting medium. From then on, Belkahia showed a clear preference for traditional materials, such as copper and ram’s skin. This was a celebration of Morocco’s pre-colonial, multicultural past, as were his many references to Amazigh (Berber) and African material culture (tifinagh signs from the script of the Amazigh language, patterns of Amazigh carpets, tattoos) and to traditional techniques, such as henna and walnut stain dyes, and the treatment of raw skin. His work brought to light the warp of the centuriesold culture, as well as popular and traditional arts that remained faithful to their historic and spiritual past. The use of these materials propelled him to make non-figurative works, developing shapes in volumes that sat between two-dimensional works and sculptural objects, which entered the viewer’s space.

Farid Belkahia, Procession 1986, dye on skin, 153 × 216 cm

© Fondation Farid Belkahia

This approach reflected his personal creative aspirations, as well as those of the Group of Casablanca, co-founded by Belkahia. It numbered artists such as Mohammed Chabâa and Mohammed Melehi, who were equally convinced of the regenerating influence of traditional and popular arts on Moroccan artists. Belkahia was able to disseminate these ideas within the Casablanca School of Fine Arts, which he directed from 1962 to 1974. With support from the art historian Toni Maraini and the anthropologist Bert Flint, the school developed a reputation for its innovative teaching: it rejected the Western academic legacy of easel painting in favour of an abstract artistic vocabulary, reformulating historical avant-gardes while remaining aware of the cultural and historical traditions of Morocco and its Amazigh, Arab-African, and Mediterranean components. This was an approach reflected in Belkahia’s now well-known saying: ‘Tradition is man’s future’.

Farid Belkahia, Jerusalem 1994, dye on skin, 161 × 421 cm

© Fondation Farid Belkahia

Farid Belkahia's Cuba Si and Tortures were purchased with funds provided by the Middle East and North Africa Acquisitions Committee, 2016.

Fatima-Zahra Lakrissa is an independent researcher in charge of cultural programming at the Mohammed VI Museum for Modern and Contemporary Art of Rabat. She was Associate Curator in the sixth edition of the Marrakech Biennale 2016 with the exhibition The Casablanca School of Art: the factory of art and history by Belkahia, Chabâa, and Melehi.