In Tate Liverpool

- Artists

-

Gauri Gill born 1970

Rajesh Vangad born 1975 - Medium

- Ink on black and white inkjet print photograph on paper

- Dimensions

- Image: 1076 × 1573 mm

frame: 1236 × 1733 × 38 mm - Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Purchased with funds provided by the South Asia Acquisitions Committee 2018

- Reference

- T14992

Summary

The Eye in the Sky 2014–16 is a large-scale black and white photograph taken by Indian photographer Gauri Gill of the indigenous artist Rajesh Chaitya Vangad (born 1975) , looking towards a landscape centred on a local mountain. The finished work is a collaboration between Gill and Vangad, who has drawn in black ink over Gill’s photograph. The image was taken in Maharashtra in western India, where Vangad was born, and the mountain is considered sacred by the Warli community to which Vangad belongs. The Eye in the Sky is a key work from Gill’s series Field of Sight, developed through collaboration with Vangad, and uses the local landscape as a field onto which the Warli encounter with urban modernity has been traced. The photographer and painter have negotiated a process through which her photographs are transformed when they become the surface for Vangad’s drawings, their collaboration raising important questions about hierarchy and access.

Thematically, The Eye in the Sky addresses the challenges faced by indigenous communities as their environment changes and natural resources are either depleted or totally exhausted. The work traces the arrival of modern technology and the relationship of the Warli to the city, the presence of Vangad himself within the image he has intervened upon adding an extra layer to this representation. Birds and other flying creatures give way to airplanes, as the simple early pictograms of everyday tasks – hunting and cooking in a landscape of rivers and foliage – transform into a cityscape. This might be Mumbai, the metropolis only a few hours from this area, where rural dwellers have had to move to sustain their livelihoods as the local economy has shrunk. Even as this work marks the disappearance of the¿ rural idyll, it also acknowledges the seduction of the city’s skyscrapers. Figures march towards it, carrying their belongings above their heads, or seated in the commuter trains that connect Mumbai to the periphery.

In many parts of India, the Adivasi, or indigenous way of life, is at odds with the ambitions of the state and corporate industry, resulting in new forms of occupation and resistance, particularly in relation to the control of natural resources. This work hints at the pervasive presence of surveillance and control, but blends this with myth and beliefs around local gods. The top of the mountain, representing the locus of the community, becomes the pupil of an enlarged eye shape that encloses and surveils the wider landscape.

Warli painting is a folk art form; the Warli are Adivasi or so called ‘scheduled tribes’ in India, whose land rights have consistently been under threat, from the period of British Colonial rule right up to the present moment of political and environmental instability. Scheduled and lower castes occupy a precarious socio-economic position in India, and their status is heavily politicised. Tribal craft, especially in the decades following decolonisation, was supported by various state and non-governmental initiatives to preserve and industrialise Indian workmanship. Vangad’s family became well-known for their paintings, developing something similar to an atelier or studio practice.

Gill’s considered photographic approach contests the perceived relationship of lens-based media with time. Instead of casual observation or snapshots, she develops series and works with themes that grow over long periods and with multiple visits to the same area or subject. She keeps returning, revisiting regularly to develop intimate relationships with the communities she enters. Since the 1990s she has worked with a family in Rajasthan, featured in her series Balika Mela (2003/2010) and Notes from the Desert (1999–ongoing). Gill’s encounter with Vangad developed through a uniquely organic process, and one with an active commitment to local narrative. He was her local guide when she became involved in a project with a local primary school. The Warli have no script for their language, only oral histories, depicted symbolically through the pictograms seen in their paintings. Originally these graphic narratives would be painted by women onto the surfaces of their homes and mud walls of the village, especially to mark important dates or festivals. Gill realised that the information from the stories she heard, which for her characterised the Warli community’s unique relationship with the landscape, was palpably absent from her photographs:

When I later saw my contact sheets, I realized that so much of the narrative that I had received from Rajesh – the great stories, which had made it come alive for me – was missing. Part of it I realized as the limitation – and unique presence of photography – to restrict what is in the image to ‘now’ … So we decided to collaborate in a more active way. Rajesh would inscribe his drawing over my photograph, meet my text with his own. Over the course of the last year, through works mailed back and forth between Delhi and Ganjad, and several subsequent meetings, particular photographs were selected by us, and each one worked upon to reflect the narratives that arose from the conversations. We restricted our work to a monochromatic palette, to make the encounter more intense, and precise.

(Quoted in Experimenter Gallery 2014, pp.8–9.)

These collaborative works perform a series of inversions, where the host, Vangad, becomes a guest within Gauri’s photographs, invited to occupy their surfaces. The ink drawings on the photographs transform both media, forcing the viewer to zoom in and look closely at the detail, and then back away and see from a distance in order to read the whole image. The dialogue between Gill and Vangad’s work allows two different ways of capturing and recording the environment to occupy the same plane, collapsing the distance between the traditional and the contemporary.

Further reading

Gauri Gill, Fields of Sight, exhibition text, Experimenter Gallery, Kolkata, West Bengal 2014, http://www.mid-day.com/articles/vangad-ways-warli-artist-lends-a-healing-touch-to-tata-memorial-hospital/15249095, accessed 26 March 2017.

Nada Raza

March 2017

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Display caption

These photographs show evidence of sea pollution in a small mangrove forest in Port Dickson, Malaysia, Gill’s hometown. Colourful plastic bags and other rubbish have washed up with the tides, getting stuck in branches and roots. In the black and white photographs, it can be hard to distinguish the waste among the plants. The first photo shows large cargo ships in the distance. This suggests the activities of Port Dickson’s commercial harbour are the source of the detritus. More widely, the series raises questions about the consequences of globalisation on the environment.

Gallery label, June 2021

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Explore

- architecture(30,960)

-

- townscapes / man-made features(21,603)

-

- tower block(152)

- townscape, distant(8,109)

- village(753)

- formal qualities(12,454)

-

- diagrammatic(799)

- photographic(4,673)

- environment / nature(315)

- history(1,983)

- actions: processes and functions(2,161)

-

- looking / watching(581)

- man(10,453)

- Asian(117)

- cities, towns, villages (non-UK)(13,323)

-

- Mumbai(9)

- government and politics(3,355)

-

- surveillance(3)

- folk art(1)

- Indian(127)

- commerce(93)

- contemporary society(640)

- displacement(24)

- industrial society(425)

- modernity(70)

- tradition(9)

- inscriptions(6,664)

-

- pictogram(1)

- agriculture and fishing(1,275)

-

- farmer(41)

You might like

-

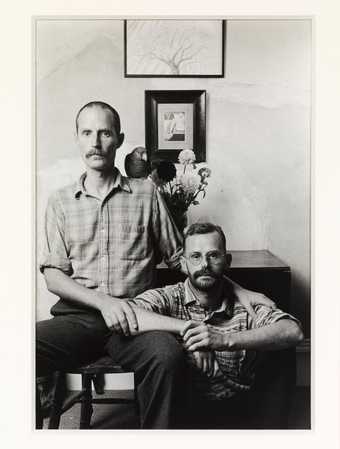

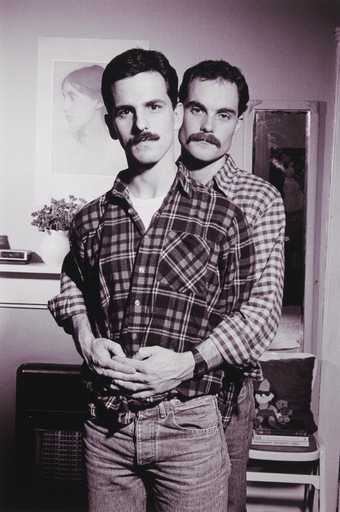

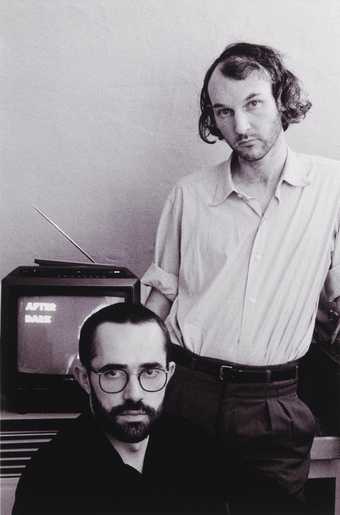

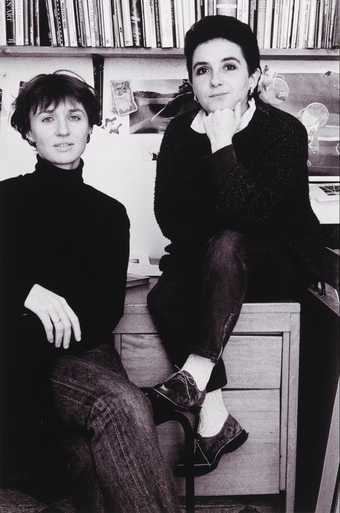

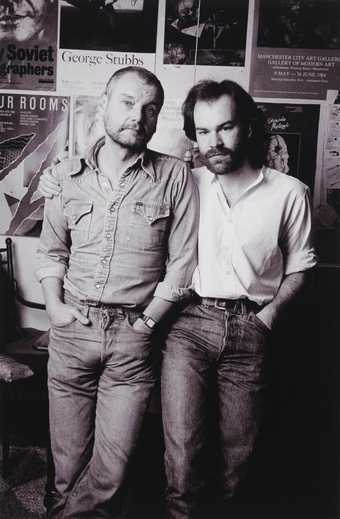

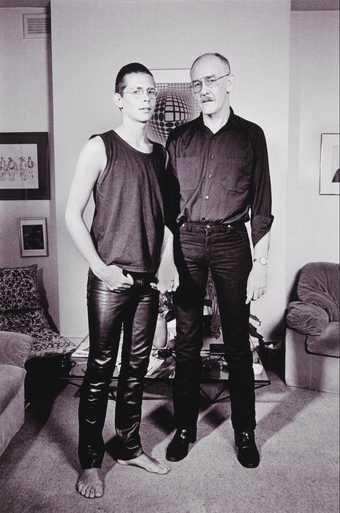

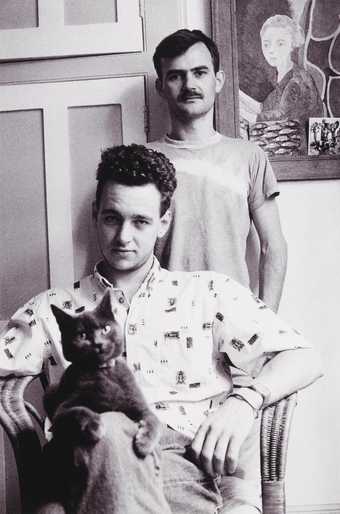

Sunil Gupta Ian and Julian, from the series Ten Years On

1986, printed 2010 -

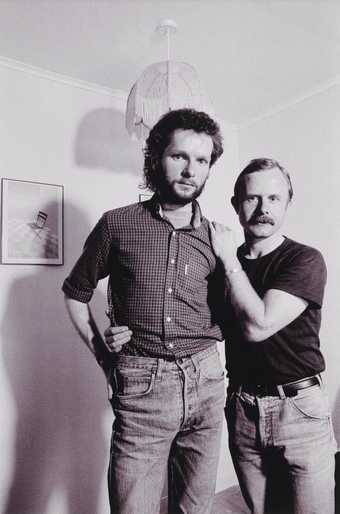

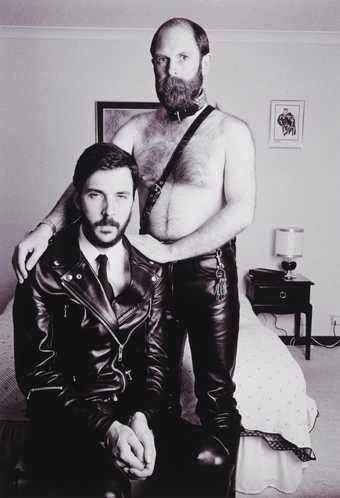

Sunil Gupta Bruno & Daniel, London

1984, printed 2018 -

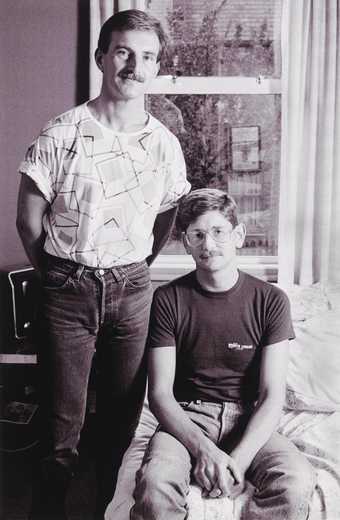

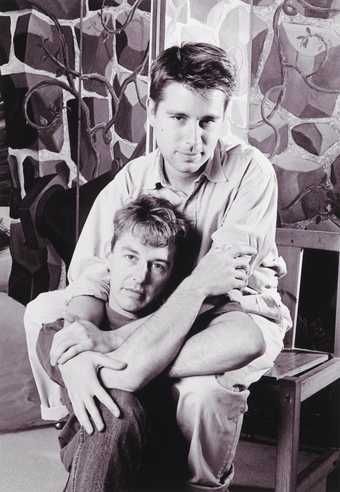

Sunil Gupta David & Peter, London

1984, printed 2018 -

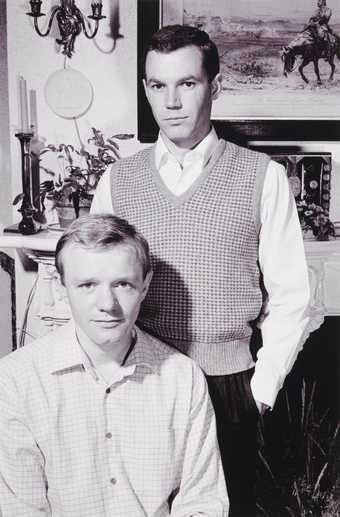

Sunil Gupta John & John, London

1985, printed 2018 -

Sunil Gupta Johnathan & Kim, London

1985, printed 2018 -

Sunil Gupta Guy & Brian, London

1984, printed 2018 -

Sunil Gupta Sue & Yve, London

1984, printed 2018 -

Sunil Gupta Emmanuel & David, London

1984, printed 2018 -

Sunil Gupta Andrew & John, London

1985, printed 2018 -

Sunil Gupta Dylan & Gerald, London

1985, printed 2018 -

Sunil Gupta Simon & John-Paul, London

1985, printed 2018 -

Sunil Gupta Karl & Daniel, London

1985, printed 2018 -

Sunil Gupta Roger & Steve, London

1984, printed 2018 -

Sunil Gupta Ian & Pavlik, London

1984, printed 2018 -

Sunil Gupta Lisa & Emily, London

1984, printed 2018