Dante Gabriel Rossetti Bocca Baciata 1859 Museum of Fine Arts (Boston, USA)

Find out more about our exhibition at Tate Britain

Dante Gabriel Rossetti Bocca Baciata 1859 Museum of Fine Arts (Boston, USA)

The poet Christina Rossetti and painter-poets Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Elizabeth Rossetti, born and known as Elizabeth Siddal/Siddall, are the most well-known of the Rossetti generation. Born into a new Victorian Age, they began as controversial figures and became international celebrities. They brought about a revolution in the arts, both in Britain and beyond.

The Rossettis’ passionate, anti-establishment personalities challenge our ideas of Victorians. They experimented with everything – art, life and love. They demanded poetry and painting express lived experience and feeling, and searched for modern beauty. Their daring stories asked questions which remain relevant today.

A note on names: The Rossetti brothers and sisters share a surname and Elizabeth Siddal (Siddall) became Elizabeth Rossetti when she married. For this reason, we have used their first names, the names they called each other, in this exhibition.

Love, Love, that art more strong than Hate,

More lasting and more full of art.From Christina Rossetti ‘What Sappho would have said had her leap cured instead of killing her’ 1848

There were four siblings in the Rossetti family: Maria (1827–1876), Gabriel (1828–1882) William (1829–1919) and Christina (1830–1894). Close in age, they were teenagers in mid-19th century London. Their parents were scholars of Italian heritage who encouraged the children to write, try their hand at art and find their own creative voices. Gabriel went to art school and he and Christina published poems when they were just 15 and 16 years old. The young siblings also worked as carers, teachers and clerks.

Christina’s verse was inspired by personal experience and popular songs and sermons, as well as poetry of all eras. The poems in this room speak of love in many voices – tender and fierce, joyful and hopeless, the love between parents and children, and even voices from beyond the grave. In her lifetime, Christina published 900 poems and today her work is still more widely known than that of her brothers.

As a teenager, Gabriel wasn’t sure whether to become a poet or a painter – he had a flair for both. The drawings in this room entwine figures in dramas of love and conflict, reflecting his enthusiasm for sensation and romance. Gabriel searched for stories in literature from around the world: popular folk ballads, Arabic tales from One Thousand and One Nights, gothic scenes from German author Goethe’s Faust, and new tales of horror by North American writer Edgar Allan Poe.

Gabriel particularly admired artists outside the establishment such as British artist and writer William Blake (1757–1827) and the satirical commentator of French modern life, Paul Gavarni (1804–1866). He sketched his own tableaux of the contemporary city. His lost drawing Quartier Latin. The Modern Raphael and La Fornarina (reproduced nearby) modernises the admired painter Raphael (1483–1520). It gives us a glimpse of the 16-year-old’s idea of the bohemian modern artist and model.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti La Ghirlandata 1873 Guildhall Art Gallery, City of London

Christina and Maria explored social justice through their writing and involvement with the Anglican Church. Gabriel and William championed revolution through art. Their father, Gabriele, was an Italian revolutionary forced to flee his homeland and the London household was often full of visiting activists. In 1848, as the children came of age, popular rebellions against political regimes spread across Europe. With the support of their family and inspired by this spirit of reform, Gabriel, William and five fellow art students founded the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (1848–53). This first British movement of modern art challenged the ‘soulless self-reflections’ of the statesponsored Royal Academy and its reliance on ‘old master’ styles and subjects of past artists such as Raphael.

The young men and women in the Pre-Raphaelites’ circle wanted to express themselves authentically with art and poetry based on lived experience and nature. Their paintings and writings explored stories from the Bible and medieval books that resonated with their modern lives. The group modelled for each other in roles that reflected these interests. Gabriel drew Elizabeth Siddal, who was studying with him, as a medieval artist painting her self-portrait. She is overseen by a lover modelled by one of the Pre-Raphaelite brothers, Thomas Woolner.

The young Pre-Raphaelites were pre-occupied with romance and searched out unusual love stories. The Rossettis found special inspiration in medieval Italy and the Florentine poet Dante Alighieri (1265–1321). Their father had devoted his career to teaching, translating and interpreting Dante’s work, which his children continued.

Dante Alighieri provided Gabriel with a model of an artist searching for beauty, love and truth in a materialistic world. His critiques of the class and political divides of medieval Florence chimed with modern Victorian London. Gabriel translated the poet’s work and even adopted his name as his own first name.

Dante Alighieri’s poems and prose were partly autobiographical. In The New Life 1294 he traced his distant adoration of Beatrice Portinari from their childhood, through their dynastic marriages to other people, to her early death. In the Divine Comedy 1320 he critiqued Italian society in the form of a journey through the afterlife – Hell, Purgatory, and Heaven – where he eventually meets Beatrice once again. This tragic love story inspired Gabriel’s poems, drawings and paintings for the rest of his career.

I care not for my Ladys soul

Though I worship before her smileFrom Elizabeth Eleanor Siddal ‘I care not for my Ladys soul’ c.1850s

The Rossettis explored the ambiguities of love in a materialistic age. Relationships were distorted by wealth, class and status and youth and beauty were often a fleeting currency. Christina and Elizabeth wrote poems in the voices of young women coerced into marriage or seduced and left as outcasts.

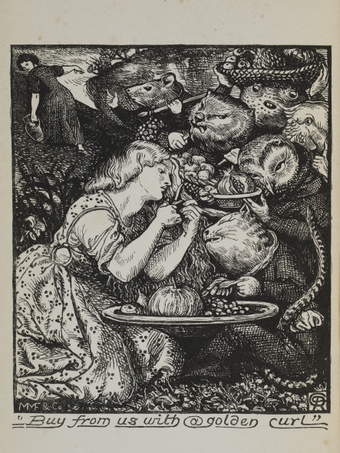

The Rossettis questioned Victorian attitudes towards women dismissed by society as ‘fallen’. A conspicuous drama of this kind was sex bought and sold in streets and places of entertainment. Christina worked in a refuge for women from this world and her allegory of feminist salvation, ‘Goblin Market’ 1859, became her most successful poem.

Sexual fall and redemption was the subject of Gabriel’s last and most ambitious Pre-Raphaelite painting, Found. His friendship with the model, Fanny Cornforth, a working-class woman, helped change his ideas and it remained unfinished. Instead, Gabriel painted Fanny in Bocca Baciata (The Kissed Mouth), which marked a new phase of his art.

During their mid-20s, Gabriel and Elizabeth worked together in his studio and had a great influence on each other’s work. Their richly patterned drawings and watercolours conjure complex, imaginative worlds. Using themselves as models, they created medieval fantasies of love and temptation, loyalty and betrayal. Complicated relationships are expressed in intricate gestures, poses and spaces.

Dialogues between Gabriel and Elizabeth’s works in this room make clear the effect they had on each other. Private collectors vied to purchase the inventive scenes of both artists, including John Ruskin. In 1857, Gabriel and Elizabeth showed work together in an exhibition of Pre-Raphaelite art held in London and New York. By this date however the couple were spending time apart. Elizabeth moved north to Matlock and Sheffield, attending Sheffield School of Art.

After her death in 1862, Gabriel preserved Elizabeth’s drawings in a photographic album, which he continued to use for inspiration.

I was a child beneath her touch,—a man

When breast to breast we clung, even I and she,—

A spirit when her spirit looked through me.From Dante Gabriel Rossetti ‘The Kiss’ 1869

The Rossettis invented new ways to love and live, which they reflected in their home environments. Although they shared many prejudices of the Victorian age, they aligned themselves with progressive ideas such as women’s rights and social reform.

By 1860, Maria and Christina had each chosen a single life. They lived together and worked in the community through an Anglican order of nuns. William would remain single until his late 40s, when he married the artist and writer Lucy Madox Brown. Meanwhile, Gabriel and Elizabeth, and others in the circle, wed and set up home together. Like several other couples in their group they came from different social classes, which was unusual for the times. These unconventional households inspired new art, dress and designs for living.

Gabriel and Elizabeth’s marriage lasted two years until she died in 1862. He traced their emotional and artistic journey in a series of poems that modernised Dante’s The New Life, which he called The House of Life.

Gabriel’s late paintings cast working-class models in fantasies, far from their modern world. This room presents studies of the people who posed for The Beloved. The lives of working-class models were rarely recorded, but recent research has expanded what we know.

Gabriel’s composition for The Beloved was inspired by Renaissance artist Titian’s painting Woman with a Mirror 1515, conceived as a Venus figure surrounded by mirrors. He adapted this into an image of the biblical ‘Song of Solomon’, about a young woman meeting her bridegroom, surrounded by attendants.

In Gabriel’s eyes, the seven figures represented a universal vision of female beauty. Created at a time when Britain was more connected to the globe through travel and colonial expansion, the figures, flowers and accessories in the painting reflect a range of cultures, particularly those from Asia and North Africa. They represent an ‘orientalist’ fantasy which mis-imagined these areas as archaic, exotic and interchangeable.

Christina Rossetti Goblin Market 1865 Tate Library & Archive (London, UK)

By the time they reached their 30s and 40s, the Rossettis’ work had won them some financial security and growing fame. Christina became a celebrity after publishing Goblin Market and Other Poems in 1862, and William worked as a leading critic and editor alongside his senior civil service career. Gabriel found success away from the mainstream, displaying work in alternative exhibition spaces and selling to private enthusiasts. He went on to lead a new avant-garde group even more influential than the Pre-Raphaelites: the aesthetic movement. This would change ideas, art and design for the second time.

Gabriel’s portraits reflected the aesthetic movement’s ideals of ‘art for art’s sake’ and a new modern beauty. He adapted the likenesses of working-class women of unconventional appearance, notably model Alexa Wilding, into fantasies of femininity. Inspired by Renaissance portraiture and mythological texts, these sensual portraits suggested touch, sound and scent as well as vision. They are characterised by many experimental changes and repainting, to emphasise the pleasure of form and colour, looking ahead to the abstract art of the following century.

The portraits were paired with poems, ‘double works of art’ where words question images and images question words. They reflected Gabriel’s complex thoughts around ‘Body’s Beauty’ and ‘Soul’s Beauty’.

Gabriel’s final years were dominated by his love and friendship with Jane Morris (born Jane Burden) (1839–1914). Jane was 18 years old and a domestic worker in Oxford when Gabriel met her outside a theatre and asked her to pose as Queen Guinevere. His team, including artist and designer William Morris (1834–1896), were painting murals based on the legends of King Arthur in the Oxford University Union. Shortly afterwards, Jane and William Morris married. Their home (the Red House, in Bexleyheath) became a creative hub where men and women in the circle experimented with designs for living. William Morris founded a cooperative design company, with Gabriel and others, which would become the family firm Morris & Co. The international Arts and Crafts movement was soon to follow.

Gabriel and William Morris shared the tenancy of Kelmscott Manor, a country house in Oxfordshire. In the early 1870s Jane and Gabriel became lovers. When they were together and apart, her presence haunted his work. Jane’s role in Gabriel’s last major paintings was little-known during his increasingly reclusive lifetime.

The Pre-Raphaelite and aesthetic movements profoundly influenced 19th and 20th-century art and literature. The Rossettis’ legacy touches our lives through romantic fiction, TV drama, fashion, advertising, interior design, fantasy, cartoons and many more aspects of our culture. Their individuality and social defiance inspire radical writers and artists to this day.

Hear more about the lives, artworks and poetry of the Rossetti generation. Led by exhibition curators Carol Jacobi and James Finch, with commentary from artists, experts and enthusiasts.

Available for £5 from the audio guide desk.

Discover the fascinating story behind this celebrated painting

Follow Glory Samjolly's step-by-step guide to painting, including modern day tips and tricks

Uncover the mysteries of this secret society of painters