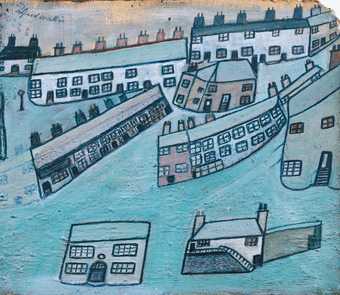

Alfred Wallis

Houses at St Ives, Cornwall

(?c.1928–1933)

Tate

For over a century St Ives has attracted artists who have new ways of looking at the world. Even David Bowie was a fan. Join Emma Gannon to find out what brought these like-minded people to the far-flung coastal town.

Want to listen to more of our podcasts? Subscribe on Acast, Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts or Spotify.

[music playing]

Emma Gannon: Hi, I'm Emma Gannon and you're listening to Walks of Art.

[music playing]

Female Speaker: Take extra care. Quite a very large gap between the train and the platform.

[music playing]

Emma: You may have heard my podcast Ctrl Alt Delete, but today I'm very excited to be guest hosting this episode for the Tate here in St. Ives. It's a coastal town in the far west of Cornwall, and home to modern arts, abstraction, pottery, boats, beaches, and a boho arts community and much more.

I was born and bred in Devon, and we used to go on family holidays to Cornwall. It's always had such a special place in my heart.

Conductor: Tickets to St. Ives, please.

Emma: Thank you. Thanks. We are on the train from St. Erth to St. Ives. I don't know much about the art history of Cornwall, but I'm really excited to find out today. Painters have been coming here since Victorian times, attracted by the life and the scenery from the 1920s, right through to the mid-20th century and beyond.

The town became a home to a league of maverick modern artists who showed us new ways of looking at the world. Alfred Wallis, Barbara Hepworth, Bernard Leach, Ben Nicholson, Patrick Heron, and Sandra Blow all lived and worked here. Even the dear departed David Bowie dashed off a painting during a visit here in the early 90s.

[background conductor voice]

Emma: It looks amazing. We're at Porthminster beach which is right next to the station, and the view is incredible. There's a few people milling about on the beach. In the far distance, you can see Godrevy Lighthouse, which is apparently the inspiration [00:02:00] behind To the Lighthouse by the amazing Virginia Woolf.

[music playing]

Emma: But what brought all these single-minded people to this seemingly far-flung place? One of those who arrived by train was the artist Terry Frost who moved with his family here at the end of the second world war. His son, Anthony, is also an artist, and he still lives nearby. He is waiting for me at the harbourside, and I can't wait to meet him.

Anthony Frost: [unintelligible 00:02:27] which happens tomorrow, doesn't it?

Female Speaker: Yes, hi.

Anthony: Hello, Emma.

Emma: Hi, nice to meet you.

Anthony: Nice to meet you.

Emma: Thank you, Anthony, for joining us on the podcast to talk about St. Ives [crosstalk] and also your dad, Terry Frost, who is going to have a permanent home in the Tate very soon. You're the perfect person to ask about all of this since you are an artist yourself, as well.

Anthony: That's true. Thank you for that.

Emma: Why do you think so many artists came to St. Ives over the years? What do you think attracts them to this place specifically?

Anthony: One of the reasons they always talk about is the light. It's almost like an island, St. Ives, and it's surrounded by 80% water, so it has this incredible reflection of the land and of the sea. One of the main thing, reasons, I think was the cheap rents and the fishermen's lofts that they could turn into studios.

As a commando in the second world war, dad got captured in Crete where he marched to Bavaria, where he is a prisoner of war for four years. When he got to Stalag 383, one of the first people he met was dear old Adrian Heath who ran an art class, and Adrian had a studio down here before he became a prisoner of war, and said to my old man, "Terry, go forth, paint. Go to St. Ives because that where it's happening."

Emma: We've just move on the corner from the harbour, and perched outside a very familiar house to you.

Anthony: 12 Key Street, my old house. Eight of us lived in here. My mom and dad and six of us, but there wasn't enough room for us all to be in one at a time. So if one came in, then one went out and went on the beach, sort of thing. [crosstalk] And it's for sale [laughs], yes, one in, one out. It's for sale now. I can't believe my old [00:04:00] cottage.

Emma: Post-second world war, when your dad came here and started to find his tribe of fellow artists, there's a lot written about his look, the beatnik look. Were people slightly ashamed of him taking on this look?

Anthony: His mom was definitely ashamed of him because he'd grown a beard and was wearing a beret and had the jeans on with turn ups and sandals.

Emma: I love that look.

Anthony: Yes, exactly. [laughs] Go to Dalston now.

Emma: Much like modern creatives now to do the work that you love sometimes you have to do other jobs to support yourself. Is that the case for your dad when he was starting out?

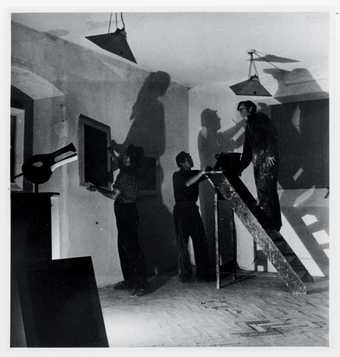

Anthony: Yes, certainly, because when he first came down here, we became a waiter. My mom worked in B&Bs and hotels, so we're changing the beds and all that sort of thing. Of course, he worked for Barbara Hepworth. You have these famous St. Ives artists, or to-be famous St. Ives artists. But they were all working for the Barbara Hepworth, as assistants to her.

Emma: By this time, your dad was established as an artist, recognized for his work. I've got one of the pictures up on the Tate website. Green, Black, and White Movement, and this is well known, this piece, isn't it?

Anthony: Yes, painted in 1951 when I was born. It's definitely to do with the harbour, St. Ives harbour, the fishing boats and the sea, and to do with movement as well. Sort of creating the rocking movement of the boats in the harbour. But this was very important because dad, when he came down here, sort of linked up with-- artists were very- they were wonderful in that sense that they were all wanted to meet each other, discuss, talk.

It was the artist, Peter Lanyon, who would take him out into the landscape, and get him to roll in the landscape, and look at the sky, and try and get a time and movement into a painting, which was like a new thing.

Emma: Here I've got up the Black and White Movement painting.

Anthony: Yes, 1952. Again, so by this time, I'm a year old. Being an artist myself, I know that sometimes paintings you think are finished are not, [00:06:00] and I know in this case that dad actually cut a piece-- physically, sword, a piece of that painting off to make it a better composition.

This piece ended up on the back of a bookcase we had. This bookcase eventually ended up with the son of my parents' great friends, on their wall, or taken off the back of the bookshelf, framed up, looks beautiful. The Tate have seven-eighths of it, and one-eighth is on the wall in Banbury, Oxfordshire. It's fantastic. [crosstalk]

Emma: Yes, that's like self-constraint, isn't it? Knowing when to stop, when to start, when not to ruin it. [laughs]

Anthony: I always think that Patrick Heron had a nice idea, when you get to the edge, just stop. [laughs]

Emma: When did you know that your dad was such a recognized painter? [crosstalk]

Anthony: I think I knew my dad was doing- up to something when he went to America. He came back from America, I should say, with presents for us here. I can remember standing in the street over there with an American cowboy hat on that my dad had brought back for me from going over to Texas, and then he won the world prize, and showed at the Bertha Schaefer Gallery in New York.

[music playing]

Emma: One of St. Ives best known painters was actually an amateur by the name of Alfred Wallis. His former home is just a short walk from where Terry Frost and his family lived. [music playing] Now I'm standing outside of his house on backroad west. He's what you'd call a bit of a late starter.

In his youth, he was a cabin boy. But once back on the shore, he opened up a boat maintenance shop and worked as rag-and-bone man, buying old clothes and household junk to sell them on. He was also reputedly the first person to sell ice cream here. I wonder if they had my favorite which is mint chocolate chip, which is pretty much all I ate.

It was only after his wife died in 1922 that he started painting because he was lonely. Chris Stevens is the director [00:08:00] of the Holburne Museum in Bath. He knows more about British modern art than most people, including me, and he is going to tell the story of Mr. Wallis and his paintings.

Chris Stevens: They're painted in a style which, I suppose, you would say as childlike. It's what at the time was called naive because he was untutored. I think he had such an urge to paint, and so little money, he painted on almost anything that came to hand. Many of the pictures are on the inside of cornflake packets or cardboard boxes that he would get from the corner shop.

There's a whole series painted on the plywood tops of tea chest. They're easily recognized because they have the nail holes around the edges. Because of that, they're also tend to be very odd-shaped. Sort of rounded corners and wobbly edges because they were just cut-out from boxes.

He didn't follow the traditional rules of perspectives that he painted a place more as he felt it and experienced it than as it might be seen in conventional paintings. His views of St. Ives bay include the island in St. Ives, Godrevy lighthouse on the far eastern end of the bay, and the distances between those has got much more to do with the experience and the importance of the places, than it has about real distances.

Where not much happens in the landscape for a sailor, then he doesn't include that.

Emma: I've got one of his paintings up on my phone called Houses at St. Ives, and it was painted in 1928. To me, it looks really modern and it's got kind of a Picasso edge to it. It's quite slanty and the perspective is all different, and you've got the same steps going up to the houses. You've got the same sort of hills and the same buildings, really. You can definitely tell that this was exactly painted right here.

Alfred Wallis's failure to observe the rules of modern art meant that no one took him seriously as an artist. That's until [00:10:00] to establish proper artist, Ben Nicholson and Christopher Wood, we're passing this very cottage, and through the open door saw this eccentric loner at work on his paintings.

Chris: The thing that was attractive about him to Ben Nicholson and Christopher Wood and others was that what they saw was a kind of authenticity that this was a sincere expression, not one that filtered through academic rules. Wallis would send him and some of his friends in London bundles of paintings, and they would make a selection of those and then send them a post order or check for those that they've kept.

Nicholson even actually tried to sort of tutor Wallis a bit. He sent him books on sailing ships, and also book on the French Naive painter, Henri Rousseau. There's a lovely letter from Wallis to Nicholson saying that he liked the book, but he doesn't do boats.

Wallis became quite widely known in the 1930s. Nicholson arranged for his work to be included in so that avant-garde exhibitions in London. He gave Wallis paintings to the Tate in London, even to the Museum of Modern Art in New York. And Wallis's letters to Nicholson-- a very sort of revealing, it's a rather awful moment when he almost says and he feels under pressure to keep making these paintings, now he's got people who appreciate them.

But he's saying that his paintings so much is making him ill, and he might have to stop. There was later quite a controversy during the second world war. He moved to the poor house in Madron, near Penzance. When he had this sort of patronage amongst these sort of quite well off and famous artists.

But the story is also told that Nicholson and others were visiting him in the poor house and found that he was, despite his sort of decrepitude, was still quite happy, and they were taking him crayons and papers that he could continue make his pictures to the very end.

Emma: I've just climbed the hill up to Barnoon cemetery where Alfred Wallis's grave is. The local council ended up burning [00:12:00] Alfred Wallis's belongings on Porthmeor beach, which is what I'm looking at right now. [music playing] I can see some surface in there quite far out, and also the Tate St. Ives is right in front of me as well. [music playing]

Ben Nicholson who remained a friend until Alfred's death did manage to save some of his paintings. He and the artist Adrian Stokes wanted to ensure that Alfred didn't have a pauper's grave. The grave was designed by Bernard Leach, and on it, it says "Artist and Mariner". It's got a lighthouse on it, and it's quite symbolic how there's someone going into the lighthouse.

Perhaps it's Alfred Wallis finally resting in piece. [music playing] Bernard Leach was working in St. Ives from the 1920s on what's the Leach Pottery half a mile from here, at Higher Stennack, is one of the most respected, influential, studio potteries in the world. Here's Chris Stevens again.

Chris: Bernard Leach was born in Hong Kong. After studying at arts school in London traveled to Japan and he was part of a revival of a potting tradition in Japan. Leach came back from Japan with a potter he'd met, that's Shoji Hamada, and it was together that they built the Leach Pottery in St. Ives.

Leach is part of this wider craft revival, which Nicholson and Wood were also part of, and Wallis was part of that, too, seeking a reconnection with something pre-industrial, both ancient, naive, and therefore more real, more authentic, more sincere.

Leach's work references very clearly both traditional English and traditional oriental forms. But he might combine that with a motif from Japan, like a well or a walking pilgrim. In the same way, [00:14:00] Leach always wanted his pottery to be used. The cups for drinking tea or beer.

To that end, actually, later he made what became called standard ware which was a range of cups and bowls and pottery which was sold in pot shops in London, to demonstrate that you could have everyday china, which didn't have to be produced in a factory, then still you see their influence.

If you go around St. Ives today, you'll see pottery made in the Leach tradition. Most of the major British potters of the 20th century works, at least pottery people like Michael Cardrew, Katherine Pleydell-Bouverie and so on. His influence was enormous in the 1950s, and he was very clearly the most famous potter in the world.

Emma: Even David Bowie himself paid a visit to the Leach pottery in 1993. While he was here, he painted an image of his wife, Iman, in the pottery. It's called Little Stranger, Metal Heart and the Black Coat. Bowie was quite a fan of the modern artist associated with St. Ives. He had a number of their works in his own personal collection, including Bernard Leach. [background noise]

Not surprisingly, the pubs at St. Ives were popular meeting places where fill and frank discussions about art took place over a few pints. The art historian, Jeanie Sinclair, is our go-to woman on this important part in St. Ives life.

Jeanie: Hi, Emma.

Emma: Hi, nice to meet you. We sat here in the Sloop with our pints. Is this somewhere where the artists would come and hang out?

Jeanie: Absolutely. It's a kind of a place where the community comes together, and often seen as a divide between the idea of artist and locals.

Emma: It's interesting that when you think about the modern world, the pubs used to be a place where you would have to go there to catch up with people, to come to the pub and actually have debates. We probably have them on Twitter now. [00:16:00]

Jeanie: Certainly after the second world war, people started to come here, different kinds of artists who were more working class, or they want them to come for money. A lot of the artists identified with the fishermen as being working class as well, and that was really important.

I think before the second world war, it was quite interesting when you read people's diaries, talking about the idea of being free from class norms.

Emma: That sort of look described as beatnik, almost like hipster type. Did people judge them or made fun of them or--

Jeanie: It's astounding, the kind of reaction that he actually got at the time. Even Alan Whicker made a TV program about it, and about beatniks in UK, and the kinds of young people that were coming to places like St. Ives and other parts of Cornwall, where mostly middle class, very young art students.

They were attracted to the idea of being a beatnik after the Jack, Cadillac on the road. It's all started to happen in the late 1950s, early, to late 1950s. People used to come down sleep on the beaches, and they just wanted to be artists, musicians and writers.

Emma: There's lots of rumors about the beatnik wall, and we were actually right by it now.

Jeanie: There's a wall opposite to the sea where beatniks would congregate. There were rumors that people would fornicate on this wall. And so there were closed town council meetings to discuss the demolition of the wall. Eventually, they did demolish the wall, simply so that people can sit on it or lie around on it, and generally make a nuisance of themselves.

Emma: I'm so fascinated by that idea of generation divides and how new- every single generation grows up thinking "I went judging on people, and I get scared that maybe one day, I'm going to be that person" and now it's baby boomers being annoyed with young people using Snapchat.

Jeanie: Yes, exactly.

Emma: The new one.

Jeanie: The people in the town [00:18:00] used to say that they were the great young washed. They head long hair, they dressed differently, they were gender ambiguous, and those- a child's cartoon from the sleep, that you can see you've got a man wearing a cravat and holding a glass of wine, and then there's a woman wearing trousers and holding a pint.

Emma: The gender stereotypes of being subverted slightly.

Jeanie: I think there is a really interesting thing about St. Ives where women in particular have feel that they have the freedom to express their gender in a non-typical way.

Emma: It's interesting that Barbara Hepworth, just because she wears jeans and has a pint in her hand, people must have enjoyed the hang up turn away, being like-- she's doing really well and she's not conforming to gender stereotypes. She was married to Ben Nicholson, and that's quite like a feminist move for her to not just take his surname.

Jeanie: She was a very modern woman. I think that's a part of the interesting thing about St. Ives is that it's often seen as a place of refuge where you can create a new kind of modernity, a new kind of society

Emma: I'm really excited to check out Barbara Hepworth's studio, are you going to show me around?

Jeanie: Absolutely.

Emma: Just before we head up to the Barbara Hepworth gardens, I'm going to see if this ice cream shop has my favorite before we go. It'd be rude not to. Hi, can I just have one scoop of mint chocolate chip ice cream, please? Thank you.

Jeanie: Here we're at Barnoon hill, and this is the Barbara Hepworth museum and sculpture garden.

Emma: Amazing. So Barnoon is the same name as the cemetery?

Jeanie: That's right, yes. [music playing] This is the garden.

Emma: That's huge. We've just walked up the high street from the [00:20:00] Sloop Pub. It's about five minute walk, and we have arrived in the gardens showcasing Barbara Hepworth's amazing work. She was quite well known before she moved here, wasn't she?

Jeanie: She was the most successful artist in Britain. One of the most well known at one point. Part of them being in St. Ives was something that brought other artists here. People like Naum Gabo, who's another famous constructivist Russian artist.

Emma: It's very tranquil and her pieces are sort of poking up behind the bamboo and the plants and all of the trees. Yes, it's incredible. Do you have a favorite one, Jeanie?

Jeanie: This is full of square walk through which is made up of four enormous bronze square panels with circles in them. One of the things I really like about this one is that as its name describes walk through, people can walk through it. Children can play around it. It looks like a giant play. [crosstalk] Yes.

That was the kind of tactility and being able to touch the sculptures and the kind of movement, and the feel of things or things that are really important to Hepworth. She didn't feel that they were static. She complained once the critics, of course, wouldn't understand her work because they just stood still in front of them and they didn't move around them, so they were very much dynamic objects for her. [crosstalk]

Emma: I like that. It's like she wanted people to use it all, at least, it's going to be a lived in piece of art. It's not just going to be like behind closed doors.

Jeanie: She had really strongly held principles and ideas about humanity.

Emma: Chris Stevens.

Chris: Hepworth was part of a generation of artists whose work was fundamentally shaped by the first world war. It very much stood for the belief in an ideal world of cooperation and harmony. That was consciously [00:22:00] developed in opposition to the rise of fascism and nazism in Europe.

The descent into war at the end of the '30s, and the horrors of the Holocaust fundamentally undermined what those artists had believed in and what they were seeking. You see I think in Hepworth and in several others, a kind of re-engagement with nature and with the landscape as a repose, I think, to the insecurities of recent times.

Sculptors like Pulegoso, this one even called landscape sculpture, which the forms of which she talks about in terms of her standing in the landscape and feeling it almost embrace her in a sort of protective hug, a calming and protective.

Emma: Hepworth and Nicholson helped nurture a new generation of artists, Patrick Heron , Terry Frost and Peter Lanyon. Many argue that it was they who influenced the American modernists of the 1950s, with the parallel exchange and ideas between the Big Apple and St. Ives.

Chris: They became the leading painters of the 1950s, not just in London but internationally, and sometimes became a place known on the international scene, so you see a numerous dealers. Not just from London, but also from New York, visiting St. Ives, even thinking about buying houses in St. Ives.

And artists, too, in a famously Mark Rothko, who may be the greatest American painter of the second half of the 20th century, visited St. Ives and stayed with Peter Lanyon in Carbis Bay, and they drove around the countryside looking for an old Methodist chapel where Rothko might put his murals, that are now in the Tate in London.

It was a place that was known internationally. Those British St. Ives artists were showing in New York, and New York artists were looking to see what was going on in Cornwall. There was a moment there when they were very much part of a kind of international phenomenon.

[music playing]

Emma: The continuing legacy of these colorful times still attracts international visitors to the [00:24:00] cobbled streets, the atmospheric pubs, and the galleries of this town. New generations of artists are still working and innovating all around the peninsula of St. Ives today, including Porthmeor studios, where Ben Nicholson, Terry Frost, Patrick Heron, and Peter Lanyon, all created their works. Many of them are on display in a newly dedicated space in the transformed Tate St. Ives gallery.

I'm Emma Gannon, and this has been so much fun doing this guest episode for the Tates, Walks of Art. For more Walks of Art podcast, and to find out about their accompanying book of the same name, visit the Tate website.

[beach sounds]

Explore St Ives

Follow in Emma Gannon's footsteps and discover the sites yourself.