Not on display

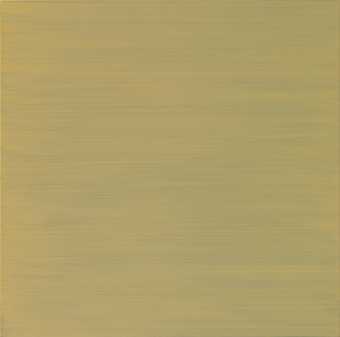

- Artist

- Mark Wallinger born 1959

- Medium

- Acrylic paint on canvas

- Dimensions

- Support: 3600 × 1800 mm

- Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Presented by the artist in honour of Sir Nicholas Serota 2017

- Reference

- T14963

Summary

id painting 29 2015 is one of a series of sixty-six id paintings which Wallinger made between late summer 2015 and spring 2016. He has referred to these works as coming out of a period in which he consciously returned to studio-based practice following an extended period of undertaking public projects (Bradley 2017, p.66). Having moved to a new, much larger studio in London than he had previously occupied, and enjoying the physical space he was able to work within, he began to think about the scale of his body in relation to the canvas. He ordered a number of canvases based on the proportions articulated in Leonardo Da Vinci’s (1452–1519) pen and ink drawing Vitruvian Man (L’Uomo Vitruviano) of c.1490 (Galleria dell’Accademia, Venice). This drawing was based on the correlations of ideal human proportions with geometry as described by the ancient Roman architect Vitruvius. Vitruvius articulated that the proportions of man are common to all and have an inbuilt symmetry: for example, the length of the outspread arms is equal to the height of a man; the measurement from below the chin to the top of the head is one sixth of the height of a man; while the foot is one seventh the height of a man. The canvases that Wallinger had made are each his height in width and double that measurement in height. This reflection of the self in the material of the work responds to the recurring theme of identity throughout Wallinger’s practice as a whole.

To make the id paintings, Wallinger dispensed with brushes and instead painted directly with his hands, using only black paint, standing just inches from the canvas and working with both hands, on the left and right of the canvas simultaneously. The proximity of his body to the canvas and the reach of his hands resulted in paintings that have a natural symmetry. To reinforce this symmetry, at a midway point in the process determined by the artist, the canvas was flipped so that the lower half could be worked on. Each of the works in the series was made in one session of two to three hours, as it was important for Wallinger that wet paint should not be applied over dry, and that the initial, instinctive marks he made should not be overpainted or edited.

The patterns that this process produced, and the fact that all of the works in the group were made using black acrylic paint, recall the form of the Rorschach ink blots used in psychoanalysis, something that is further reflected in the works’ titles. Each of the paintings in the series is titled id painting and then numbered consecutively in the order of their making. Id refers to Sigmund Freud’s theories that the ‘id’, a primitive and instinctive element of personality, is driven by the pleasure principle and operates wholly subconsciously and unaffected by reality. The physical proximity of the artist to the canvas in making these paintings has led him to describe the process as ‘almost painting blind’ (ibid., p.66), reiterating the sense that they are subconscious or instinctive works.

Wallinger’s process means that these paintings are both the remains of an event or action and paintings in their own right, giving them the double meaning or layering of ideas that is a dominant feature of the artist’s practice. The works also relate to his interest in the state use of surveillance cameras and the idea that our bodies, as filmed on CCTV, are often unwitting witnesses or evidence in an endless series of incidents. It is possible, therefore, to read the artist’s physical relationship to the canvas as witness to the action of painting, but also as ‘standing up’ to it or to some implied external force.

The id paintings were displayed in two concurrent exhibitions held at the Fruitmarket Gallery, Edinburgh and Dundee Contemporary Art titled Mark Wallinger Mark, the two exhibitions mirroring each other and the title itself reflecting not just a play on the artist’s name, but the symmetrical nature of the works, in addition to the direct ‘mark’ making of the artist.

Further reading

Martin Herbert, Mark Wallinger, London 2011.

Sally O’Reilly, Mark Wallinger, London 2015.

Fiona Bradley, Mark Wallinger Mark, exhibition catalogue, Fruitmarket Gallery, Edinburgh 2017, illustrated p.59.

Linsey Young

May 2017

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Explore

- abstraction(8,615)

-

- non-representational(6,161)

-

- gestural(891)

- emotions and human qualities(5,345)

-

- subconscious(62)

- symmetry(220)

- Freud, Sigmund(17)

- Vitruvius(1)

- surveillance(3)

You might like

-

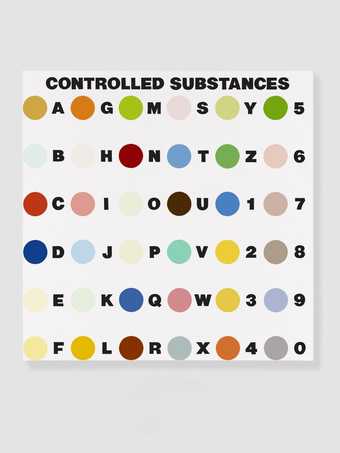

Damien Hirst Controlled Substance Key Painting

1994 -

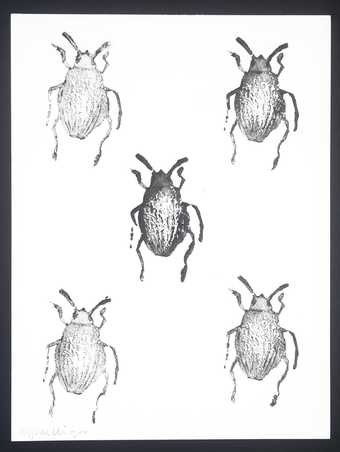

Mark Wallinger King Edward and the Colorado Beetle

2000 -

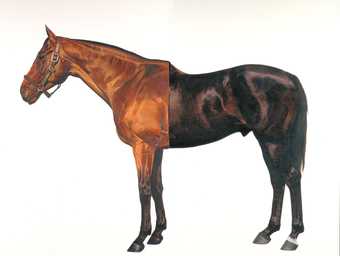

Mark Wallinger Half-Brother (Exit to Nowhere - Machiavellian)

1994–5 -

Maria Lalic History Painting 8 Egyptian. Orpiment

1995 -

Maria Lalic History Painting 17 Italian. Naples Yellow

1995 -

Mark Wallinger Angel

1997 -

Wilhelmina Barns-Graham June Painting, Ultramarine and Yellow

1996 -

Gary Hume Water Painting

1999 -

Mark Wallinger Prometheus

1999 -

Mark Wallinger Hymn

1997 -

Mark Wallinger Sleeper

2004 -

Mark Wallinger Threshold to the Kingdom

2000 -

Mark Wallinger Construction Site

2011 -

Mark Wallinger State Britain

2007 -

Mark Wallinger They Think It’s All Over... It Is Now

1988