In Tate Britain

Prints and Drawings Room

View by appointment- Artist

- Charles Turner 1774–1857

- Medium

- Engraving on paper

- Dimensions

- Image: 172 × 120 mm

- Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Purchased 1987

- Reference

- T04842

Catalogue entry

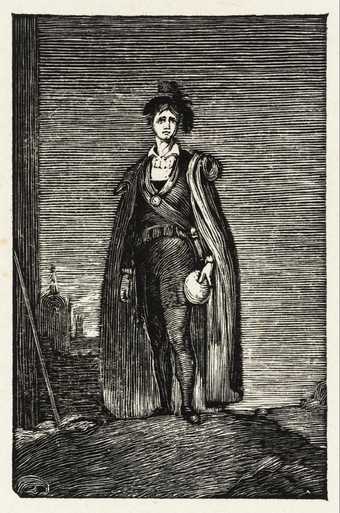

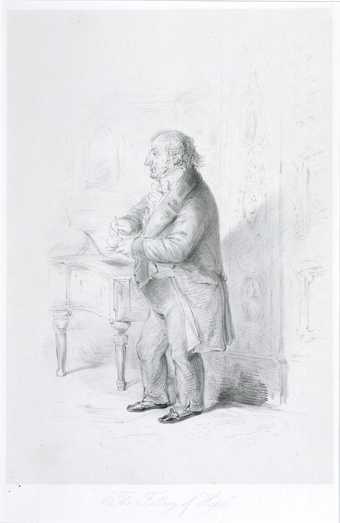

T04842 Portrait of J.M.W. Turner pub.1852

Stipple engraving 172 × 120 (6 3/4 × 4 11/16) on India paper 237 × 160 (9 5/16 × 6 1/4)

Engraved inscriptions: ‘Engraved & Etched by Yours Truly’ below image at centre and facsimile signature ‘J.M.W. Turner’ below image b.r.

Purchased (Grant-in-Aid) 1987

Prov: ...; N.W. Lott & H.J. Gerrish Ltd, from whom bt by Tate Gallery

Lit: A. Whitman, Charles Turner, 1907, pp.201–2, no.574

The two Turners met in 1795 as fellow students at the Royal Academy and enjoyed a long friendship interrupted, but not destroyed, by arguments arising from Charles Turner's activities as an engraver of his namesake's work. The future engraver's drawing of a scowling J.M.W. Turner, made shortly after they met and ironically inscribed ‘A Sweet Temper’ (British Museum), was an all too accurate forecast of what was to come.

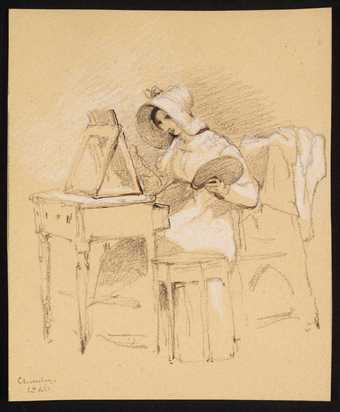

T04842 is one of several retrospective portraits of Turner drawn and engraved by Charles Turner from 1841 on. The first, and essentially the model for the others, was a drawing in black and white chalks and watercolour of Turner in profile to right, aged about forty; it is inscribed ‘Dream 1841’ and ‘Made the morning after the Dream, by CT’. It is now in the British Museum and a copy, in the same media and dated 1842, is in the National Portrait Gallery (R. Walker, Regency Portraits, 1985, I, p.508, no.1182, II, pl.1261). The ‘Dream’ evidently recalled to Charles Turner his namesake in vigorous middle age. Subsequently, and after the painter's death, Charles Turner produced two prints dependent on the drawings. The second of these, a mezzotint published in 1856 (Whitman 1907, no.573) is essentially the same type extended to a half-length; Turner is shown seated under a tree, holding a sketchbook open to the composition of his 1836 painting ‘Mercury and Argus’ (National Gallery of Canada; M. Butlin and E. Joll, The Paintings of J.M.W. Turner, 1984, no.367). Charles Turner's use of recollected or second-hand material in his portraits is explained by the painter's refusal to give him sittings - an inconvenience glossed over in the prospectus to the mezzotint as ‘the unfortunate circumstances I had to contend with’. In T04842, the earlier of the two posthumous prints, Charles Turner used the head originating from the ‘Dream’ of 1841, turning it to a profile to left, and combining it with a more youthful and presentably dressed version of the body in the lithograph after Count D'Orsay's drawing, published by J. Hogarth in 1851 (see After Count Alfred D'Orsay, T05029 above). As in D'Orsay's design, Turner is seen in a room, this time in his studio with some of his pictures.

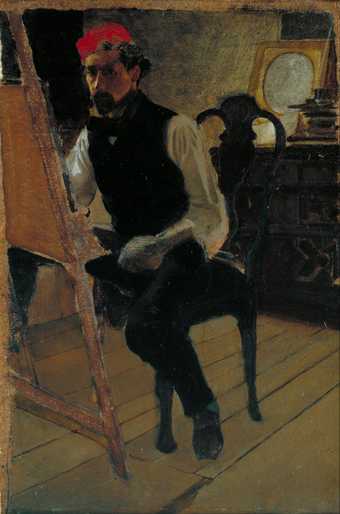

In choosing these pictures within a picture, Charles Turner clearly took the opportunity to stress his own professional involvement with his subject and his art. The shipwreck subject resting on the chair is not the 1805 oil in the Tate Gallery (N 00476; Butlin and Joll 1984, no.54) but the mezzotint which Charles Turner had published in 1807 both in black and white and coloured impressions (W.G. Rawlinson, The Engraved Work of J.M.W. Turner, II, 1913, pp.362–3, no.751). This print, the first reproduction of a painting by Turner, had originally been proposed by the engraver himself. It marked a turning point in the careers of both Turners, and its great success helped to determine the choice of the mezzotint medium, and of Charles Turner as principal engraver, for the Liber Studiorum in 1807. On the wall behind hangs what appears to be Charles Turner's only other coloured mezzotint after his namesake, ‘The Burning Mountain’ (ibid., p.382, no.792), engraved apparently in 1815 after the painting ‘The Eruption of the Souffrier Mountains’ exhibited that year (University of Liverpool; Butlin and Joll 1984, no.132). Two months before Charles Turner engraved this portrait, the Turner collector John Dillon noted on the impression of ‘The Burning Mountain’ now in the British Museum that the print was already extremely rare, having been engraved ‘for a gentleman who took it - copper plate, impressions and all, abroad ... only three impressions were left in England’. Apart from the scarcity of this particular print, both it and the ‘Shipwreck’ were the only coloured mezzotints ever issued after Turner's work, and were achievements of which the engraver could legitimately be proud. Moreover, they could both be taken as marking the beginning and end of the breach between the two Turners. Characteristically, the painter had insisted upon his personal supervision of every published coloured plate of the ‘Shipwreck’, but the engraver was either unable to prevent, or had himself colluded in the publication of pirate impressions, one of which the painter discovered in a print shop window. The angry correspondence that took place in 1810 (J. Gage, Collected Correspondence of J.M.W. Turner, 1980, pp.43–4, no.35) compounded the financial disputes that had arisen since at least the previous year over the Liber Studiorum, for which Charles Turner engraved the first twenty plates. The engraver later claimed that the ensuing rift lasted nineteen years (J. Pye and J.L. Roget, Notes and Memoranda Respecting Turner's Liber Studiorum, 1878, p.60), but the engraving of ‘The Burning Mountain’ in 1815 must argue for a much earlier reconciliation, or at least a resumption of professional contact. Moreover Gage (1980, p.290) adduces from Farington's diary that the painter probably favoured the engraver's election as Associate Engraver in the Academy the previous year. It is perhaps not surprising that this portrait of Turner makes no direct reference to the Liber, although the sketchbook open in the painter's hand may allude to it obliquely, displaying as it does a subject reminiscent of several of the classical or Claudean plates in the series. The two larger pictures on easels at the right in T04842 cannot be identified.

A drawing of this subject was recorded by Whitman in the possession of Charles Turner's granddaughter, Miss Savery.

Published in:

Tate Gallery: Illustrated Catalogue of Acquisitions 1986-88, London 1996

Explore

- interiors(2,776)

-

- workspaces(918)

-

- studio(549)

- clothing and personal items(5,879)

-

- umbrella(91)

- mahlstick(4)

- paintbrush(90)

- painting materials(62)

- palette(73)

- sketchbook(42)

- book - non-specific(1,954)

- actions: postures and motions(9,111)

-

- standing(3,106)

- man(10,453)

- individuals: male(1,841)

- inscriptions(6,664)

-

- name of sitter(44)

- arts and entertainment(7,210)

-

- artist, painter(2,545)

You might like

-

George Jones [title not known]

date not known -

John Linnell [title not known]

published 1843 -

John Henry Foley Sir Joshua Reynolds, P.R.A.

date not known -

Sir John Everett Millais, Bt Charles I and his Son in the Studio of Van Dyck

1849 -

Alfred Stevens An Artist in his Studio

c.1840–2 -

John Thomas Smith Portrait of J.M.W. Turner, R.A.

date not known -

Alfred Stevens William Blundell Spence

c.1851 -

Sir John Everett Millais, Bt Serjeant Ralph Thomas

1848 -

Charles Samuel Keene Self-Portrait

date not known -

Dante Gabriel Rossetti Study for ‘Giotto Painting the Portrait of Dante’

1852 -

Dante Gabriel Rossetti St Catherine

1857 -

Charles Hullmandel, after Count Alfred D’Orsay Portrait of J.M.W. Turner (‘The Fallacy of Hope’), engraved by J. Hogarth

published 1851 -

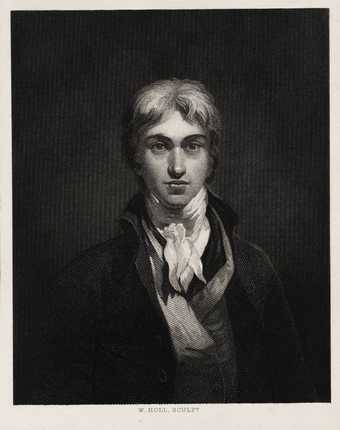

After Joseph Mallord William Turner Portrait of Turner, engraved by W. Holl

published 1859–61 -

After Joseph Mallord William Turner Statue of Turner (Turner Gallery frontispiece without lettering)

published 1859–61 -

After Joseph Mallord William Turner Statue of Turner (Turner Gallery frontispiece without lettering)

1859–61