Late on Saturday, 30 October 1841, a spectacular fire broke out at the Tower of London, the ancient fortress guarding the city by the River Thames. As part of Tate’s ongoing cataloguing project investigating its holdings of over 37,000 watercolours and drawings by J.M.W. Turner (1775–1851), several vivid and expressive watercolours of this event in the Turner Bequest have been newly identified (see figs.1 and 2, each previously known as ‘The Burning of the Houses of Parliament’). Breaking out north of the famous turreted keep, the White Tower, the fire centred on the Grand Storehouse. This vast seventeenth-century red brick and stone English Baroque building stood on the site of the present Waterloo Barracks and housed historical armoury collections. The fire raged for several days, and the Crown Jewels, kept nearby, had to be hastily rescued.

Fig.3

William Oliver

Conflagration of the Tower of London on the Night 1841

UK Government Art Collection

Correspondents in the Morning Chronicle wrote of the ‘surpassingly grand’ scene and the ‘lurid glare’, with ‘multitudes gazing horror-struck’, while the Times described ‘a truly national calamity’ and flames of ‘a livid hue of a most unearthly description’, which ‘exceeded in grandeur even the great fire at the House of Commons’ – a significant comparison in relation to Turner. It is rare for longstanding identifications of his works to be radically altered, but the nine watercolours in question (Tate D27846–D27854), originally consecutive pages of a sketchbook, have been associated for over a century with a more notorious London fire, the catastrophic nocturnal destruction of the Houses of Parliament beside the River Thames at Westminster in October 1834. Turner is reported to have observed that event at first hand, and exhibited two major paintings the following year (now owned by the Philadelphia Museum of Art and the Cleveland Museum of Art). There is also a dramatic, unfinished watercolour that indisputably shows that event (Tate D36235). All share an elemental palette based on red, yellow and white against shadowy blue and black, but the somewhat indistinct architectural features in these nine loose, atmospheric and apparently spontaneous watercolour studies have long puzzled scholars, who have ingeniously attempted to correlate the few legible details with those of Parliament and its riverside setting.

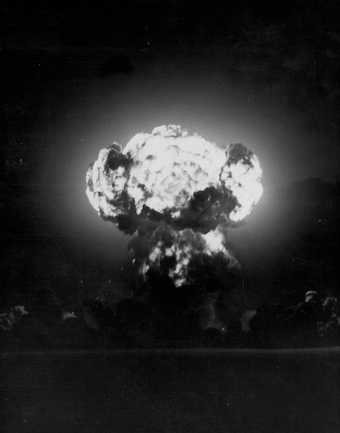

In the course of detailed new research, other London fires were investigated. Contemporary colour prints of the 1841 Tower fire, such as William Oliver’s The Conflagration of the Tower of London (fig.3) chimed immediately with aspects of Turner’s views. They show the flames through rows of tall windows and the roof of the Storehouse with its central clock tower, with large crowds watching from across the broad moat on three sides. This, rather than the Thames, is the water surrounding the site of the fire in Turner’s views; the dark masses immediately beyond are the towers and walls of the outer defences, and the fierce redness of the burning building emphasises the brick construction of the Grand Storehouse. In the most developed view, Turner appears to indicate the building’s clock tower and classical pediment, with the pale silhouette of the White Tower beyond (fig.4).

Fig.4

J.M.W. Turner

A Fire at the Tower of London 1841

Tate D27847

The handling, strong colour and lack of detail indicated a date fairly late in Turner’s career. Aside from their being natural signifiers of the fire and its setting, the primary colours used here sit well with Turner’s relatively unmodulated use of them in the ethereal watercolour sketches made on his Swiss tours of the early 1840s. Fortuitously, in 1841, he had returned from Switzerland a few days before the fire broke out. He quickly applied for direct access to the Tower, but was rebuffed by a typically brusque note from its Constable, the Duke of Wellington, on 3 November: no-one was to be admitted ‘except on business’.

Turner had a long-standing interest in the pictorial possibilities of fire, beginning as a precocious teenager with the aftermath of the Pantheon conflagration in London’s Oxford Street in 1792 (Tate D00121; Turner Bequest IX A). He knew the Tower well in calmer circumstances, making more conventional designs for engravings of 1795, 1831 and 1833, all showing the cupola of the Grand Storehouse juxtaposed with the White Tower. In practical terms, the frequently rehearsed arguments in the context of the 1834 Parliament fire, as to whether Turner made the nine watercolour studies on the spot in the course of the event, remain unresolved in the context of 1841. Assuming he even witnessed the fire directly on the first night or in the course of the next few days but given that he is known to have been averse to sketching directly from nature in watercolours (even in favourable circumstances unhindered by smoke, darkness and crowds), it seems most likely that he would have worked on them back at his London studio, to spectacular effect. Sadly, as far as we know, he did not take the subject further.