Ten Years Alive on the Infinite Plain is a complex performance and multimedia work that consists of a live performance by a musical ensemble and a projectionist. The work was created by the filmmaker, artist, musician and teacher Tony Conrad in 1972, and was directed and performed by Conrad at least eleven times until his death in 2016. The musical ensemble is complex, comprising two violins, a bass guitar and a ‘long string drone’ – an instrument developed and made by Conrad himself.1 The projections include a film by Conrad featuring a vertical stripe pattern that creates optical effects that become wave-like as a result of the movement of the projectors throughout the performance. When this work was proposed for entry into Tate’s collection in late 2016, the present authors, as part of our remit as time-based media conservators, were determined to keep open the possibilities for the work’s future activations.

This essay discusses the experimental process undertaken in trying to understand the artwork and conserve it in its multiplicity. This process was undertaken by a team comprising researchers within the project Reshaping the Collectible: When Artworks Live in the Museum, which is funded by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, and members of the time-based media conservation department at Tate. Both the project and the time-based media conservation teams were interested in assessing if the documentation we would produce as part of the acquisition of this work would be enough to activate the work once it was acquired. Was the documentation able to transmit specific information needed for the artwork to remain the same across its many iterations? Additionally, was it able to trigger moments of variation in the artwork’s relation with different groups of performers and different contexts of activation? In addressing these questions in relation to Ten Years Alive on the Infinite Plain, this text explores wider issues of materiality and variability, transience and permanence, uncertainty and change.

The essay will start with a situated account of the time-based media conservation team’s encounter with the work in 2016–17 and the involvement of the Reshaping the Collectible team from 2018 onwards. The sections that follow will describe the process of developing and testing a methodology for transmission based on written and multimedia documentation – which the Reshaping the Collectible researchers and the time-based media conservators have come to call the ‘dossier for transmission’. As well as explaining how the dossier was produced and tested, we will focus on the theoretical underpinnings that guided the development of a method that included both the creation and the evaluation of documentation – a stage that we refer to as the ‘fieldwork experiment’. In discussing the possibilities afforded by the approach we are presenting here, we will also highlight what we have learned, what we have changed, and how this process has influenced Tate’s current strategies for acquiring and conserving performance art.

Getting to know Ten Years Alive on the Infinite Plain

Ten Years Alive on the Infinite Plain (hereafter Ten Years Alive) first came to the attention of the Time-Based Media Conservation team when it was proposed for acquisition in December 2016. We began to look at this work in earnest once we knew that it was going to be performed in the South Tank at Tate Modern, London in January 2017.2

Tony Conrad died in 2016, and the event at the South Tank was the first time Ten Years Alive was to be performed without Conrad acting as both its artistic director and one of the performers. To activate the piece, Tate worked with a group of people who had been involved in previous activations of the work as performers and were close collaborators of Conrad at several moments during his life.3

In the context of this activation, Tate curators, researchers and time-based media conservators held a meeting with the artist’s estate, which at the time was directed by Conrad’s widow Paige Sarlin; a representative from Greene Naftali Gallery, who was facilitating the acquisition of the work; and the aforementioned collaborators of Conrad’s who were participating in the activation of the work.4 This meeting was fundamental in initiating the discussion around the artwork’s significant properties and contexts, and in allowing us to start discovering the relevant information needed to activate the work in the future. One of the main conclusions from this exchange was that the artwork had no specific score, with performers relying on their past experiences of playing the piece to make it happen. With Conrad’s violin being replaced by an audio track of him playing it during a previous performance of the artwork, we knew that we were witnessing some of the changes to the artwork’s biography firsthand.5 In this case, the change would alter the exchange that occurred between the performers and both the violin part once played by the artist, and Conrad himself. All stakeholders within this meeting left with the aim to pull together information that would inform the understanding of the artwork.

Following the 2017 activation, our work in acquiring Ten Years Alive slowly continued, as the time-based media team worked through the collected video footage, interviews and transcripts that were captured and created from the South Tanks performance. Our efforts in 2018 coincided with the beginning of the Reshaping the Collectible research project, and this artwork was proposed as a key case study for the project.

Our early awareness of the artwork’s eleven previous activations led to us mapping its material history. Mapping the material history of artworks is a process that allows conservators to identify the material conditions of the works’ various activations. This includes understanding, for example, what equipment and materials were used and for what; who has been involved in curating, producing, directing and performing the work; where the activations have taken place; and the interactions between the social context and the materiality of the work. In other words, writing a material history consists of understanding how artworks evolve, how and why they change, and how those changes are the traces of decision-making processes that are both material and social.6 The archival research on the many lives of Ten Years Alive – much of which involved searching the internet for materials relating to previous instantiations of the work – unveiled a material history characterised by variability. Indeed, while we were aware that the artwork had been shown in venues of different types, with different numbers of performers and projections, we had not been aware of the extent of those variations across the performances.

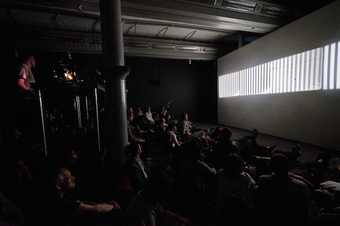

Fig.1

Advertisement for the concert series of live and electronic contemporary music at The Kitchen, New York in March 1972 that featured the first performance of Tony Conrad’s Ten Years Alive on the Infinite Plain

Courtesy Tony Conrad Archives and Greene Naftali, New York

The first instantiation of the work was its performance at The Kitchen, New York on March 1972 (fig.1). This now-iconic event brought together Conrad, musician Rhys Chatham and artist and musician Laurie Anderson, and the musical performance was eventually released on vinyl by Superior Viaduct in May 2017.7 The 1972 instance, however, is far from being representative of Ten Years Alive as Conrad did not use film projectors to project the vertical stripe patterned film, instead using a video created by Steina and Woody Vasulka. Another substantive change in the artwork’s biography relates to the title of the work. In 2007 Conrad decided that the artwork known as Ten Years Alive on the Infinite Plain would thereafter be titled X Years Alive on the Infinite Plain, in which ‘X’ was calculated by subtracting the year Conrad declared his experiments started – 1962 – from the current year.8 The differences in the material history of the work made it hard for us to decide who to contact in trying to determine which characteristics of the work that are essential to it and which ones could (and should) exist in flux. The distinction between these two types of characteristics also seemed to be particularly challenging to frame as our knowledge of the various activations of the work became more and more nuanced.

Considering the artwork’s multiple instances of variation, and given the absence of the artist and the lack of an authorised score or set of instructions, it became evident that our current methodologies for transmitting the work would need reflection and development to ensure Tate could effectively preserve Ten Years Alive for the future.9 The interviews conducted in January 2017 with the performers who participated in the activation of the work in the Tanks (Rhys Chatham, Angharad Davies, Dominic Lash and Andrew Lampert) seemed to indicate that each performer had a different, complex task of their own. For example, while the violinist had the role of responding to the recording of Conrad playing the violin, the bass player was to define the rhythm of the piece in very clear and steady intervals. The interviews also showed that Conrad relied on curator and producer roles to instantiate the work in various locations in the later stages of his life.10 The importance and complementarity of these different approaches to the work suggested that capturing the voices of those involved in them would be essential to ensure the knowledge transmission necessary to activate Ten Years Alive. It was clear to us that the documentation produced for a work like Ten Years Alive would have to accommodate different roles – those of the event producer, the violinist, the long string instrument player, the bassist, the projectionist, and even the sound engineer. These people would be essential to the activation of Ten Years Alive and they all needed tailor-made guidelines that allowed them to understand the work within their own practice. It was also clear that many of the features of the work would likely depend on nuanced ways of playing with musical or projection technology that would be very difficult (if not impossible) to describe in our documentation. The knowledge embodied by the performers who intimately collaborated with Conrad would be essential, and the teams involved in this research were keen to see how and if we could create new communities of practice as part of our conservation strategy.

Introducing the idea of a dossier

The term ‘dossier’ was first mentioned by filmmaker Andrew Lampert during the January 2017 internal workshop that was held to discuss the artwork’s acquisition. In referring to a dossier, Lampert was developing the concept of a tool that could transmit this artwork beyond the structure and connotations associated with the notion of a ‘manual’. This was prompted by a question from conservator Louise Lawson, who asked: ‘If we, in the future, loan this piece to an institution, is there particular information that you would like us to share, beyond the manual, so that they can get a full understanding of the piece? It just might be worth considering that so it’s not just a PDF that goes to them, but it’s some more comprehensive information.’11 Lampert replied: ‘I think it is like a dossier … with a manual for performance and installation indications within.’12 While a ‘manual’ would consist of a document with practical guidelines to activate the performance, make film prints or create the sound installation,13 a ‘dossier’ would add other relevant documentation such as video and audio documentation to those guidelines.

Another useful term mentioned by Lampert is that of an ‘oral manual’,14 which bestows the idea that a lot of the knowledge shared by past collaborators and performers resists being written or documented. Paige Sarlin, moreover, suggested that documentation within the dossier could be differentiated between ‘teaching documents’, which would be highly relevant to performers learning how to activate Ten Years Alive, and historical information, which would be pivotal for understanding the artwork in its historical context.15 The latter could include documentation, such as selected video and audio of past performances, writings by Conrad, and interview transcripts.

The idea of a ‘dossier’ was further explored in various internal project team meetings that took place from October 2018, and in a separate internal meeting with the time-based media conservation team on 31 January 2019. The teams discussed the different affordances of the notions of both dossier and manual, as well as the role of the dossier, with the time-based media conservation team also thinking how it could make use of or relate to existing documentation structures, such as our collections management database (The Museum System, or TMS), digital repository and workflows. The dossier was discussed not only bearing in mind the specific case of Ten Years Alive, but also as a structure and concept that could potentially be applied to other, similarly complex artworks in the future.

For each individual artwork in the collection, the conservation department sets up what we call an ‘artwork folder’. This folder is created in both paper and digital forms, with the digital one being saved on a shared server and the paper one held at Tate’s collection centre. The digital ‘artwork folder’, which is backed up daily, is shared across different conservation teams and holds various forms of documentation such as installation instructions, condition reports, images, emails, and documents supplied or produced during acquisitions, loans and exhibitions. Many of these documents continue to evolve during an artwork’s life in the collection and are therefore editable, rather than fixed according to when they were written.16 This is the case for instruction documents such as display or performance specifications that will need to reflect changes in the biographies of artworks.17

The artwork folder structure currently in use by some conservation teams at Tate is as follows:

- Introduction

- Specification for Display

- Structure and Examination

- Display History

- Acquisitions and Registration

- Conservation, Strategy, Research, Treatment, Ongoing

- Artist Participation

- Art Historical, Research and Context

- Images

This folder structure was largely developed during the research project Inside Installations: The Preservation and Presentation of Installation Art (2004–7).18 According to the project’s booklet, the structure was the ‘result of the functional analysis of a range of conservation and research files for installation works’19 and was developed at a workshop organised at Tate in collaboration with Frederika Huys (a conservator at SMAK in Ghent) and facilitated by Elizabeth Orna, an independent expert in information management.20

Sections 1–8 of the folder structure were developed during the workshop. Subsequently, following the removal of a dedicated drive within Tate’s servers for the management of images, a ninth folder was added (‘9. Images’), which is used to create an image index of the artwork. Many other subfolders can be created within the overall folder structure. This is the case, for instance, with ‘4. Display History’, in which a new subfolder is created to correspond to each new activation of an artwork, be it a display, an exhibition or a loan out.

In the case of performance artworks, the time-based media conservation team often either produces or is supplied with audio-visual documentation. We are keen to collect audio-visual documents holding key content on how to activate a performance that are ideally approved by artists or their estates. We similarly look for opportunities to capture the ways in which an artwork unfolds over time and how it is shown in different contexts.21

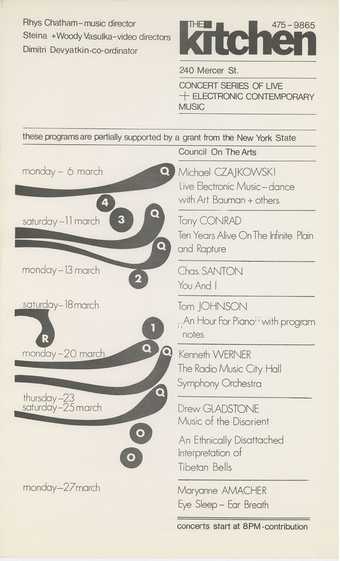

Fig.2

Diagram showing how the dossier for transmission is created by carefully pulling and curating data from different storage systems at Tate: the ‘artwork folder’ saved in a shared server and Tate’s digital repository

Image: Ana Ribeiro, April 2020

Given that Tate usually collects or creates both documents that change over time – such as the performance specification – and documents that are meant to be stable – such as the audio-visual documentation from previous performances, the idea was to create a ‘dossier for transmission’ that would be collated by pulling relevant data from different locations in the artwork folder and in Tate’s digital repository (see fig.2).22 A single, fixed, permanently located digital entity called ‘the dossier’, therefore, does not exist. Every instance of the dossier is created with up-to-date documents each time the artwork is set to be activated. In our understanding of the term, the dossier can therefore be defined as a group of carefully selected documents that are set up in a curated structure, which both evolve over time and are collected with the intention of providing the basis for transmitting an artwork every time activation is required.

Methodology for developing the dossier

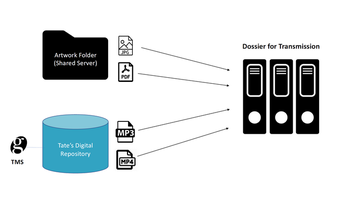

The efforts to define what the ‘dossier’ would look like worked in parallel with the process of understanding what the artwork is and its multiple material configurations over time. It was not long after both the Reshaping the Collectible project team and the time-based media conservation team started thinking about creating a dossier that we understood that the archival sources detailing the differences in the material manifestations of the work were limited. It became clear that other sources had to be explored, specifically the experiences of people who participated in the performance of the work. While some of those aspects could be gathered through interviews, we were still concerned about everything that cannot be said – all of the tacit knowledge that emerges from the practice of the performance, or what performance studies theorist Diana Taylor has called ‘the repertoire’.23 Our main concern at the time was that the teams were assembling a whole body of documentation without knowing if it was sufficient to fulfil its mission of creating the conditions for the work to be activated in the future. We therefore developed a methodology for creating and testing a dossier of documentation based on three main stages with intermediate phases: creating the dossier, testing the dossier, and revising the documentation and long-term strategies for the care of performance art (fig.3).24

Fig.3

Diagram showing the methodology for developing the dossier

Image: Hélia Marçal, February/November 2021

Creating the dossier

The dossier for Ten Years Alive was created between September 2018 and May 2019.26 To do so, the time-based media conservation and project team worked with Conrad’s estate, led by Tony Oursler (who took over from Paige Sarlin as the head of the estate in 2017) and Greene Naftali Gallery. Conversations were initially held with Andrew Lampert with support from Regina Greene. The initial idea was to see what kind of dossier each of the two groups – Tate and the estate – would produce, and to compare this in order to form a broader view of what the dossier could be. This, however, was not possible due to time constraints and the need to move forward with our fieldwork experiment and the acquisition. It would have been interesting to see what the estate and its representatives would have proposed for the dossier structure, as this would have brought in an additional dimension and opportunity for discussion and comparison beyond our own thinking. The dossier was in fact developed in tandem with our research, not only influencing the pathways the researchers in the Reshaping the Collectible project were exploring as part of their own research, but also being influenced by both the data that were being collected and the collective learning promoted by periodical debrief meetings with all the people involved. While we were undertaking our research, Lampert provided us with a document entitled ‘Ten Years Alive on the Infinite Plain Manual’ (2019).27 This document proved a useful resource and its contents were moved into different sections within the dossier structure. The dossier had many versions, changing with each new piece of information, and was itself iterative and multiple.

Archival research into the artwork’s material history had allowed the project team and the time-based media conservation team to map some of the people who had collaborated with Conrad in multiple instantiations of the work. These included long string drone players Rhys Chatham and David Grubbs, violinist Angharad Davies, and bass players Laurie Anderson and Dominic Lash.28 To better understand how the artwork had been materialised in the past and the material conditions needed to activate it in the future, we opted to conduct semi-structured interviews with some of these individuals. Semi-structured interviews are an established method for conducting artist interviews within contemporary art conservation,29 and are commonly used as a qualitative methodology in ethnographic fieldwork settings.30 The interviews were aimed at collecting impressions about how the performers learned the artwork, the forms of input they had before and after their interactions with Conrad, how they remembered Conrad’s interaction with them, and how that framed the ways in which the artwork was materialised. This approach was grounded in scholarship stemming from memory studies, an interdisciplinary field that investigates, among other things, how people remember. To focus this inquiry on how people remember events in which they participated in some way, the project team looked into studies on testimony and witnessing and how they were framed methodologically.

The selected interviewees were past performers in or curators of the multiple instantiations of Ten Years Alive. Since we were asking them to remember details from events that took place many years ago, testimonial recollection seemed to be a particularly generative operational concept and methodology for this experiment. The psychologist Jovan Byford writes that there are some aspects of testimonial accounts that link to the notion of witnessing. Byford explains that ‘a testimony, as a form of legal evidence, always attests to the veracity of some event’, which makes ‘the witness who is called upon to provide testimony [someone who can be] seen as being in possession of some privileged, authoritative perspective’ that stems ‘either from his or her proximity to facts, or from the immediacy of their experience’.31 Although this characterisation seems to reflect the positioning of the groups of performers that collaborated with Conrad in the production and activation of Ten Years Alive, it was important not to frame their recollection as a form of truth-telling, but as a situated account of a personal, quasi-autobiographical perspective. Knowing that it would be hard to remember an event that had happen many years ago, we decided to follow what has been called a witness-focused approach.32 In looking beyond what Byford calls ‘the evidentiary value of testimony’, the interviews were less focused on the specific details of the event as they were on the memories the performers had about how they had performed the work, or on the anecdotes that remained in their memories after all those years. We hoped that the focus on their own experience, rather than on facts related to the event, would trigger them to remember how the artwork was shown in each context.

The interviews and testimonies gathered were essential in filling in some of the gaps in the material history of the work. This also allowed us to understand the reasons for some of the variability in the ways the artwork was materialised; for example, the use of three projectors in one activation was due to one of the projectors breaking just before the performance. The interviews also made evident Conrad’s involvement during the rehearsals, where he often revised some aspects of a performer’s action.

These testimonies were, however, insufficient in providing solutions for practical aspects particularly related to the nuances of handling and positioning the projections. Our understanding of the projectionist role was grounded in the aforementioned manual provided by Lampert. In this document, Lampert defines the parameters for the performance from his experience, providing new projectionists with guidelines and practical tips, from how to prepare the film to the timings of the performance. Using this document, the time-based media conservation team was able to survey some of the characteristics of the performance, such as that it starts with four projections side-by-side on a screen or white wall; that the projections are supposed to move towards the centre of the screen, overlapping during the final minutes of the performance; and that the sensibility required to move the projectors during the performance is partially embodied, to a point that it is almost impossible to transmit those nuances in a narrative form, either verbally or via written documentation.

Other challenges emerging from the projectionist role related to the spatial settings of the room where it was set to be activated as part of our experiment – Tate Liverpool’s Wolfson Gallery. The position of the projectors at Tate Liverpool was complicated by the structure of the Wolfson Gallery, which has two sets of columns placed around the central wing of the space. Projecting a stable, linear image is particularly difficult if the projectors are not placed with enough distance from the screen, as the projections can produce a distortion known as a keystone effect.33

Fig.4

The projectors undergoing testing at N-Space, Tate Store, London, March 2019, using dummy film stock

Photo: Hélia Marçal

Due to these issues around the projectors, it was important to test this aspect of the performance by replicating the conditions of the Wolfson Gallery, which we were able to do at Tate Store in London in March 2019 (fig.4).34

The curators leading on the acquisition, Andrea Lissoni and Carly Whitefield, and the curator and projectionist Mark Webber joined the project team and time-based media conservation team in discussing the layout of the projectors. Webber, who had been the projectionist for Ten Years Alive in its activation at the festival Expanded Cinema: Film als Spektakel, Ereignis und Performance (Expanded Cinema: Film as Spectacle, Event and Performance) in Dortmund in 2004, explained how he had manipulated the projectors and what, for him, was their ideal initial position. The curators were able to recollect some of their own experiences in the production of this artwork at Live Arts Week in Bologna in 2013 (in the case of Lissoni) and at Tate Modern in 2017. This was a foundational step in the creation of the documentation as it allowed for a deeper understanding not only of the materiality of the projectors and the film, but also of how these influenced the performance. It also facilitated decision-making around specific projector requirements such as the type and number of projectors to use and the height of the projection platform.

The information collected from the interviews and testimonies, the projection tests, and the manual written by Lampert, together with the knowledge we had gathered in 2017, led to the development of the first version of the dossier and the first versions of key documents for integrating into the artwork folder for Ten Years Alive. These were mainly the performance specification and ‘teaching documents’, to use the terminology employed by Paige Sarlin,35 such as ‘Instructions for Projectionist’ and ‘Instructions for Musicians’.36

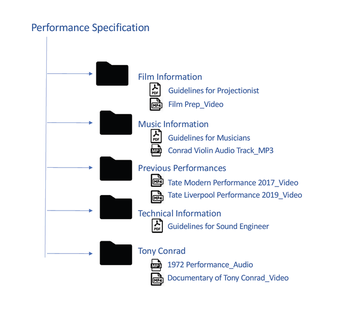

Fig.5

Diagram showing the structure of the first version of the dossier for Ten Years Alive

Image: Ana Ribeiro, April 2020

The first version of the dossier (fig.5), which was shared with performers and other stakeholders in May 2019, was made up of eight folders and one ‘read me’ file containing information on how to navigate the structure. The key element binding all the supporting documents in these folders was the performance specification found in the first folder. The performance specification also gives an overview of Ten Years Alive and describes its requirements for activation.

The second folder provided performers with historical context on the work and its musical background. This included key musical references such as albums by Conrad and works by experimental artists from the 1960s and 1970s, for instance La Monte Young.

Teaching resources were organised into two different folders, one with essential resources for musicians (folder three) and another with essential resources for the projectionist (folder four). Further documentation relating to previous activations of the performance was shared in folders five to eight, including audio of the first performance in 1972 and rehearsal and full video documentation of the performance at Tate Modern in 2017.

Testing the dossier

Two questions central to our experiment in Liverpool were: is it possible to transmit a complex performance using documentation? If so, was the documentation we had created enough to transmit Ten Years Alive? To assess the reliability of the dossier as a source and means for transmitting the work, the experiment had to include a performance by professional musicians who had never performed the work before, and a group of people with enough knowledge and experience to evaluate such a performance. To achieve this, the project and the time-based media conservation teams set up a process whereby the new performers were invited to learn the artwork from the dossier, and a group of trusted witnesses of previous events were invited to provide feedback on the performance.

Fig.6

The new generation of performers preparing for the activation of Ten Years Alive at Tate Liverpool, 15 May 2019. From left to right: Catherine Landen, George Maund and Emily Lansley

Photo: Roger Sinek

One of the key aspects we had to consider was the nature and composition of the two groups. In order to source a new generation of performers, the dossier was sent to a producer in Liverpool, Andrew Ellis, who selected three musicians to perform the work: Catherine Landen, a violinist, George Maund, a guitar player, and Emily Lansley, a bass player (fig.6). Rob Kennedy, an artist and time-based media specialist who had experience in both film projection and installation settings (including at Tate) was chosen to be the projectionist. Those selected to provide feedback and evaluate the performance were drawn from the musicians, curators and projectionists that had been involved in past performances of the work. This group we named the ‘transmitters’. The transmitters were: Rhys Chatham, long string instrument player in the 1972 and 2017 performances; Angharad Davies, violinist in the 2006 performance at Dundee Contemporary Arts and in the 2017 performance; Dominic Lash, bass player in the 2017 performance; Peter Spence, projectionist in the 2006 performance; and Xavier García Bardón, co-curator of the performance in 2007, which was held at BOZAR, the Centre for Fine Arts in Brussels. This group of trusted transmitters was joined by Andrea Lissoni, at the time Senior Curator of International Art at Tate and the curator of the 2013 performance, and Carly Whitefield, Assistant Curator of International Art at Tate. The project team also invited two academics from Maastricht University to act as observers: Vivian van Saaze, Associate Professor of Literature and Art, and Harro van Lente, Professor of Science and Technology Studies.

The project team and time-based media conservators spent between two and six days in Liverpool in what could be described as a period of fieldwork. We tried to create a schedule for this fieldwork experiment that considered the various decision-making and learning moments that would occur through the interactions between the musicians, the projectionist, their instruments and equipment, Tate staff, and the transmitters. For the experiment to work, we had first to determine what the transmitters could recall from their own experience, while also understanding what their expectations for a performance of Ten Years Alive would be. Semi-structured interviews that followed the above-mentioned witness-centered approach were essential for creating this baseline, which also served as a trigger for the memories of the transmitters.

As we were interested in knowing how new performers learned the work, we devised a structure for the fieldwork consisting of distinct ‘moments’ during which they could explore their immediate experiences in understanding and practice the work. Those moments were structured as follows:

- The distribution of the dossier to performers two weeks in advance.

- The performers meeting up and rehearsing together for one and a half days, with the possibility of one full dress rehearsal before the presentation to transmitters.

- The presentation to transmitters: a closed, ninety-minute performance for a select group of people with expert knowledge of the work.

- A feedback session to allow the performers to hear expert feedback from the transmitters on first impressions of the performance.

- A public performance as part of Liverpool’s LightNight.

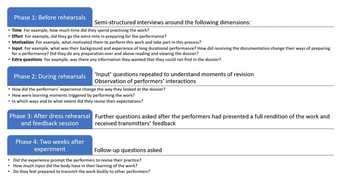

As part of the fieldwork, performers were interviewed on arrival, ahead of the first rehearsal, and were asked about their experience of learning the work specifically from the dossier. This interview was essential for understanding the baseline knowledge they had about the artwork before they started to communicate and work together. The semi-structured interview scripts in this case followed four dimensions that modern languages scholar Mary Louise Pratt has determined are essential for the transmission of intangible cultural heritage: input, effort, motivation and time (fig.7).37 Some of these questions were repeated throughout the various stages of the fieldwork experiment, which consisted of multiple interviews at various times, as follows:

- Phase 1: Prior to rehearsals, before the performers had had time to work collaboratively on the content of the dossier.

- Phase 2: During rehearsals, while the performers were learning how to collaboratively articulate the information provided by the dossier.

- Phase 3: Following the closed performance and feedback sessions, after the performers had had the time to perform a full rendition of the work and hear the feedback from transmitters.

- Phase 4: Two weeks after the experiment, once the performers had consolidated their learning and had time to look back on the whole process.

This fieldwork structure allowed us to collect data on the progression of the performers’ understanding of the work through the experience of interacting with the dossier and negotiating the boundaries of the performance of the artwork together.

Fig.7

Diagram showing various phases of the interviews with the new generation of performers

Image: Hélia Marçal, February/November 2021

Through the interviews it was clear that the time the performers spent together was essential to the process of learning the artwork and in understanding its materialisation in the space. For instance, all three musicians reported inconsistencies in the dossier that made the tuning rather challenging. This was due to the fact that the experiences of previous performers, captured in the dossier via interviews, differed when it came to the tuning for the work. The musicians also indicated that the producer, Andrew Ellis, had directed them to the footage of the 2006 performance in Dundee prior to them receiving the dossier.38 Interestingly, all members of the ensemble established the performance in Dundee as the baseline of their initial conversations, which might have altered the way they perceived and understood the documentation that was available to them in the dossier, as this footage was not provided as part of it.

Another challenge emerged with the handling of the long string drone. Guitarist George Maund was tasked to play the instrument conceived by Conrad. Maund’s experience dealing with and developing DIY instruments seems to have been pivotal in his interactions with the long string drone. The process started with the tuning of the instrument. The metal body of the instrument was causing the low frequency tones of the sound it produced to resonate as it emerged from the PA system, disturbing the performance and causing parts of the metallic lighting panels in the gallery to become loose and fall. This highlighted to us the importance of the sound engineer who, together with Maund, tried resting the instrument on tables made of a variety of different materials, including solid wood, solid metal, and a table with a wooden top and metal legs. The chosen option was a solid wooden table with a blanket placed underneath the long string instrument, as this resonated most successfully within the space. The sound engineer also replaced the strings that had been provided with the guitar-like instrument when it was acquired.

Fig.8

The performers rehearsing at Tate Liverpool, 16 May 2019

Photo: Roger Sinek

Performers from the new generation echoed the remarks of some of the past collaborators of Conrad, stating that rehearsals were the place where they pushed the boundaries of the work and tried to understand what the various media that make up Ten Years Alive could bring to their performance (fig.8). The words of Rob Kennedy, the projectionist in Liverpool, clearly illustrate the importance of this phase as a trigger for developing the practice of the work:

I guess the intention was to really play with the equipment as much as possible to see how you can change the imagery … Without doing it, you can’t really get the feel of how things change … [D]uring the rehearsal, what I wanted to do was just to try to see the breadth of what was possible with those four different [projected] images. Thinking about the different speeds that they were running and how each projector was slightly different in terms of the kind of temperature of the light that it was projecting.39

Fig.9

Fieldwork participants discussing the closed performance during the feedback session, Tate Liverpool, 16 May 2019

Photo: Roger Sinek

Another key moment that was widely referred to by the new generation of performers as being significant for their apprehension of the work was the feedback session that was scheduled directly after the closed performance (fig.9).40 The session started with the question ‘So, was this Ten Years Alive on the Infinite Plain?’, to which the curator Xavier García Bardón answered yes, with some sticking points.41 The discussion continued with participants sharing their stories and experiences of Conrad and of the artwork, and how they felt these experiences contributed to their feedback on the performance that had just happened. The discussion was essential to further understanding the nuances and the boundaries of the work and what makes the artwork the artwork. It was interesting to see how much of the artwork’s identity is brought together through subtle forms of embodied practice, such as the speed and intensity of the drone sound that comes from the long string instrument, or the smooth variation of focus in the projections.

Following the feedback session, the transmitters approached the new generation of performers and started to give them direct feedback about ways to perform the artwork. This process was not planned and resembled one of body-to-body transmission,42 which consolidated some aspects of the performance for the new generation of performers, particularly Catherine Landen, the violinist.43 The transmitters also seemed keen to exchange ideas and interact with the instruments. This moment further consolidated our realisation of how much of the performance was brought together through those interactions, and how the multiplicity of voices that was evident in the documentation also needed to exist during the performance itself.

Although our fieldwork ended with the public performance at Tate Liverpool, the experiment continued afterwards, with some follow-up questions being asked to the performers two weeks later (see fig.7, phase 4). Among the questions asked, one referred to future transmissions of Ten Years Alive: ‘Do you think you would be prepared to now act as a transmitter of this work?’. Two of the four performers answered this question positively, which in itself may be an indication that the experiment had worked.

Reflecting on the dossier and methodology

Our experience of putting together the dossier and collecting the data during the fieldwork experiment formed the basis of our reflection on the dossier and methodology. After the experiment we analysed the content of the data gathered in the two instances of data collection: the activations of the artwork in 2017 and 2019.44 This fieldwork identified what would need to be revised, clarified, added to and omitted from the dossier, resulting in an altered structure and associated content for the dossier being created in October 2019 (fig.10). Our reflections on the methodology itself focused on the rehearsal, the closed performance and the feedback session. This section will describe and discuss these findings and changes in full, and will reflect on how we can take these processes forward for use within our future practice.

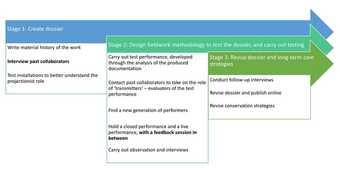

Fig.10

The revised structure of the dossier, created in October 2019

Image: Louise Lawson and Ana Ribeiro, April 2020

Revisions to the dossier

The revisions to the dossier started by focusing on the inconsistencies identified by the performers, which varied from wording and terminology, to the use of specific of footage, to the naming of documents. Firstly, the word ‘improvisation’ – which has different meanings across different musical cultures – created uncertainty, as it was not clear to the performers how much space they had to improvise or to expand the work through their own practice. In one of the follow-up interviews, projectionist Rob Kennedy mentioned that he was not clear on whether his performance was meant to reference the activation of the work at Tate in 2017 or if it was meant to bring out a new, bespoke perspective on what the artwork was and could be. We feel that this question arose due to the dossier’s reliance on documentation captured in 2017, since this was the main footage we had access to at the time of the dossier’s creation. The folder containing ‘Previous Performances’ has subsequently been expanded to include the Tate Liverpool performance in order to move away from the emphasis on a single activation in the dossier. There was also ambiguity in communicating the goals of the activation to the performers. This may have been heightened by the naming of the documents as ‘instructions’; if they had been called ‘guidelines’ or ‘perspectives’, this would have provided a more open-ended context for their interpretation. Key documents were therefore changed to use the word ‘guidelines’.

As mentioned above, another inconsistency lay in how the tuning was described. The dossier aimed to capture different views, accounts and voices, and this led to difficulties in knowing how to approach the tuning of the instruments for the performance. This was amplified by the fact that the video of the 2006 performance in Dundee was shared with the performers by Andrew Ellis prior to the dossier’s dissemination. This somewhat influenced the reading of the dossier, with the Dundee performance becoming the key reference for the musicians. Violinist Catherine Landen observed:

There have been quite a few different messages about the tuning, actually, because in the ... video they base it around a D, but then in the 2017 video it’s around the C#, and then I think in the dossier as well, at some points it says a C. So, it’s quite inconsistent as to what it’s based around. And that’s actually really important … We were just saying earlier, we don’t understand how it can be anything different to the C# because of the Tony Conrad track, that’s what his violinist tuned to. So, if we’re all playing a semitone out with that, that would be really jarring for ninety minutes. So, I think there’s a bit of inconsistency in the dossier as regards to that information.45

The work now uses the audio track of Conrad playing the violin, and this has influenced the tuning of the instrument to C#. This situation highlighted the need to make visible the variations that have existed, while emphasising the current reliance on the audio track. Landen’s account makes an argument for guiding the musicians to listen to the audio track of Conrad playing the violin, as it would better support them in their conceptualisation of the performance. The dossier now confirms that the instruments should be tuned to C#.

It also became clear to us that the violinist had one of the hardest parts: theirs was a supporting role as they had to play along with Conrad’s audio track. We had to communicate this in the dossier without referring to the usual role of the second violin in musical practice, as Conrad did not endorse forms of hierarchy in his practice and in the performance of this work. The balance that was needed to play in support of another violin but without being secondary to the audio track was particularly hard to transmit, and the interaction between the transmitter and the performer was crucial for us to understand and address this nuance.

Moreover, further clarification was needed in the dossier regarding how the performers should finish the performance. We revisited how the artwork should end by confirming the order each performer finished in and cross-referencing this information with testimonies from the transmitters.

Clarifications within the dossier

As practitioner-researchers coming predominately (and yet not exclusively) from the field of conservation, we approached the challenge of creating a tool for the transmission of Ten Years Alive as a new area of learning that encompassed a need to understand the musical language and culture of the work; the different forms of performance practice; and the nuanced, tacit knowledge carried by the musicians and projectionists. Crucial to this was the inclusion of a multiplicity of voices in the dossier itself. To finalise the music-related sections within the dossier, for instance, we decided to ask one of the musical performers to read and edit them to ensure they accurately reflected the requirements of a musician.

We tried to rehearse different possibilities for acknowledging the different voices in the written documents, making evident the variability of the performance and the collaborative process that led to the dossier’s development. This collaboration was driven and made possible through the evolving nature and structure of the dossier. Reshaping the Collectible’s ambition to ‘make the invisible visible’ led to the development of an approach to contributorship that would allow proper acknowledgement of all the voices in the dossier.46

Our first attempt at this involved us including the initials of each contributor after each contribution that they had made: these initials were placed against statements or sentences to indicate different voices. Reflecting on the performance specification, we soon understood that this first form of citation was confusing and was not accurate or specific enough to provide the context of a particular contribution and how it was brought into the dossier. We decided to annotate the performance specification using detailed footnotes to accommodate the specificity of all the contributions. These footnotes now reference not only the contributor, but also related documents, interviews and other processes of data collection, while also allowing for future decision-making processes to be noted and justified. This is particularly relevant for us in the time-based media conservation team as it allows us to build on our institutional memory regarding Ten Years Alive. It means that we can track decision-making processes within the team and analyse their triggers. We anticipate that having this additional information in the performance specification will also be important for new performers. The annotations will allow new performers to grasp the inherent variability of the work, and to better understand moments of decision-making impacting the artwork and how it is materialised over time.

Additions to and omissions from the dossier

In addition to the above changes, we decided to make a key addition to the dossier, as it was necessary to make much more evident the importance of Conrad’s personality in making and activating the work. The awareness of his presence, even in absentia,47 was one of the main outcomes of the experiment we undertook both in developing the dossier and in testing the documentation in Liverpool. The initial performance specification contained an artist statement, selected by Andrew Lampert, and a document entitled ‘Playing Principles of Tony Conrad’. These highlighted the importance of reflecting who Conrad was as a person and prompted us to include more material that revealed aspects of his personality and wider work. For the revised version of the dossier we created a new folder entitled ‘Tony Conrad’ that could include audio-visual content, such as documentary film, that brings out his personality and shows some of the ways in which his presence and playfulness was so important to his artistic practice.

Some characteristics of the work itself make written documents a difficult choice for transmitting the ways in which it is learned and performed. In this sense, it was clear to us that some structural aspects of the dossier would have to be changed for the future. The revised structure of the dossier was influenced by how performers approached the work. They relayed different perspectives on the information they received from the dossier: Catherine Landen and Emily Lansley both mentioned they felt it was too much information for them, as they mainly worked with the audio track. Landen said ‘we just wanted to read all the notes that the musicians made last time and the general background to the piece’.48 Rob Kennedy and George Maund, on the other hand, shared an appreciation for the plethora of stories and the in-depth look into the artwork, with Kennedy saying that ‘reading the interview with Tony Conrad talking about the relationship between his music and his film was really helpful’.49 Maund said he was impressed with the level of care being afforded to the work, stating: ‘I think the dossier is so thorough and so lovingly put together and full of these very occasional, beautiful contradictions, which allow for a sense of play.’50

All four performers agreed that it was quite hard to understand which information was relevant to their specific role, and that a clear route to learning the work seemed to be absent. We changed the wording of the folders to ‘Music Information’ and ‘Film Information’ to try and create a clear pathway to the relevant documentation in each case. The performers’ account was also echoed by the sound engineer, who mentioned that the dossier had little to no information for his technical role, which impaired his approach to the artwork, at least in early rehearsals. We addressed this by creating a folder for ‘Technical Information’.

As part of these revisions we streamlined the content within the dossier, with the amount of information and the overall folder structure being reduced in extent. This involved omitting media pertaining to the rehearsals of the 2017 performance at Tate Modern. We have added in the footage from the 2019 performance at Tate Liverpool in order to remove the onus on the Tate Modern version and to promote the variation and multiplicity that exist within the work.

The changes to the dossier outlined above helped make evident the variations that are at the core of the artwork’s material history and reframed the various contributions to the dossier in a way that makes them more visible and complete, while also improving its readability. The dossier will be reviewed and reflected on with each activation of the work, so the structure will be open for revision and development based on new information and learning.

Methodology: rehearsals, closed performance and feedback

This section reflects on three of the key ‘moments’ in the fieldwork experiment: the rehearsal, the closed performance and the feedback session. Rehearsals were critical for the boundaries of the work to be practiced and articulated between performers and their instruments in the setting at Tate Liverpool. They were also essential in showing how the process of learning and playing the work unfolds through interactions, which, as mentioned, was particularly important for the tuning of the instruments. Violinist Catherine Landen described this as follows:

We started off tuning the long string drone to the right pitch, and it takes a while for it to settle down. And then we decided to actually tune to the bass guitar more, because Emily is kind of the middle register between us. So, the drone is the lowest, she’s kind of in the middle octave, and then I’m on the top octave. So that’s a good grounding for us to actually try and tune our instruments. And in some ways, it’s challenging, because the strings go out of tune because it’s not the standard tuning for the instruments. So, it’s trying to keep a check on that. But that will settle down over the next couple of days as we stay at pitch. And just really listening to [Conrad’s pre-recorded audio] track as well. Making sure we’re as in tune as we can be with the track, because obviously that isn’t possible to change. So, we can kind of fine tune what we’re doing a bit to match that as well.51

The closed performance and the feedback session were also crucial for the evaluation of the dossier, as they brought together the transmitters with the new generation of performers. Even though each transmitter had been interviewed multiple times prior to this moment, coming together brought new memories to the fore that were essential for the feedback session. The transmitters reported that the process of being interviewed beforehand helped them to remember the artwork, somehow rescuing memories that were not so present at the beginning of the process. Each transmitter came with their own collection of experiences, which, together with their generous accounts, led to rich exchanges with the new generation of performers both in the feedback session and during the day that followed. Angharad Davies, a transmitter who had played the violin in the 2006 and 2017 renditions of the work, brought her diary with her and shared her accounts from the first time she participated in the activation of Ten Years Alive:

I wrote in my diary about this piece and I found it yesterday, so I’ve got it in the hotel, so I can share it. [Laughter] Not everything. But I wrote down that I’m worried about putting the violin down, because my left hand is hurting and if I put it down, I may never be able to pick the violin back up again. So, this piece for me is a real physical piece. It’s physically demanding. And I remember sitting next to Nikos, and Tony said, ‘Of course, you can stop if you get tired, it’s fine.’ Just before the performance Nikos and I looked at each other and Nikos said something like, ‘Are you going to play all the way through?’ And I said, ‘Yes, I am.’ [Laughter] And we just played all the way. Well, we tried to play all the way through. Now, that’s not to mean that if something starts hurting, that you don’t adjust and move around a bit. But, I think, if you’ve got that extra preparation in mind, that it’s going to be a physical thing, it really brings, yes, something deeper to the performance.52

Somewhat diverging from the design of the methodology, the transmitters and the new generation of performers went through an impromptu second round of feedback after the official feedback discussion. This was a much more practical session in which the transmitters worked with the new performers and fed back through their interaction with the instruments and projectors. This interaction continued to the day of the public performance as preparation for the performance began. The transmitters began providing more insights into their own experiences and practice, transmitting some aspects of the work to the performers both verbally and with their bodies. This made it evident that some aspects of the work simply cannot be described and have to be performed through body-to-body transmission: for instance, the position of the violin against the performer’s body, the amplitude of the movement and the strain in the upper arm. Such interactions were essential for the performers, with all reporting changes in their understanding of the work. As Landen observed on the day of the performance:

Then, yes, there are quite a lot of changes that we’re going to make for tonight, so it was a really useful experience as well. There are so many things that came up ... and it’s been so helpful to have. And the performers that have played before, because there are so many things that they thought about, the balance of the instruments and lots of technical things as well, that we wouldn’t have known really if they hadn’t been there. So that was great.53

After the fieldwork experiment was completed, further feedback was received. An email was sent to all participants asking about their experience of the experiment. Results showed that although all participants enjoyed participating in the experiment and found real value in the learning that was co-created by the group, others felt the applied methodology to be somewhat constraining, and would expect to see more flexibility in future efforts. Two of the transmitters said they had been expecting to be able to be in touch with the new generation of performers prior to the experiment in Liverpool. However, they did acknowledge that keeping the transmitters and the performers separate until the fieldwork began did make sense for evaluating the dossier’s ability to transmit the work to the new performers.54

For the team working to acquire and conserve the work, this methodology was useful in understanding how an artwork such as Ten Years Alive is conserved and transmitted; how it is learned, and how it can be taught. The time-based media conservation team is still trying to understand what material conditions are needed for the long-term preservation of this work and, equally importantly, how those conditions may change in the future. This experiment has highlighted that the conservation of complex performances is a collaborative process that is dependent on the knowledge, practices and networks that sustain them. The final section of this text will discuss some of the preliminary steps that the time-based media team is undertaking to further explore ways of safeguarding the future of complex performance works in their nuanced and multiple materialisations.

Next steps

The aim of the methodology and experiment was to explore whether documentation would be enough to transmit artworks like Ten Years Alive. It was important to test the documentation produced by the time-based media conservation team and to understand its capacity to trigger moments of learning in new generations of performers. By analysing the results obtained through this experiment, we will now reflect on how the design of the research has influenced the outcome and examine the future possibilities of extending this model of experimentation further.

Through this process the authors have learned that the level of information in the dossier still requires further reflection and testing, with a specific focus on the structure and the dissemination strategy. The structure that we are now using refers to the roles of the performers, providing a clear path for the musicians, projectionists and sound engineers that will likely allow a new generation of performers to engage with the dossier more effectively. Further testing is still needed, however, to understand how successful the new version of the dossier will be. Regarding dissemination, in the fieldwork experiment all of the information in the dossier was provided at once. This would not necessarily happen in practice: information would be issued in a staged or staggered way in response to the development of a future display of the work. The dissemination within normal working practices and processes needs further exploration and this will be done at the point of the work’s next activation. This will allow for a further point of reflection and demonstrates the ongoing process of our work.

The time-based media conservation team will continue to develop its strategy for conserving performance, ensuring that the level of care and attention provided by so many people in the development of the dossier for Ten Years Alive can continue.55 The experiment has demonstrated that while the dossier is successful in supporting the transmission of the work, Tate has to rely on the social networks that have been built around Ten Years Alive to sustain communities of practice that can participate in transmission and activation efforts. People working at Tate are also part of those communities, as are the performers that joined us in Liverpool. Together, we are expanding these communities and the knowledge base needed to continue to perform the work, with past performers joining Tate in transmitting the work to new performers in each activation. With new generations of performers becoming transmitters themselves, we expect to establish the intergenerational transmission of Ten Years Alive as a collection care strategy for this work at Tate. The readers of this essay and the other texts published alongside it are now part of this network. The revised dossier has been made available online, allowing it to have as many interpreters as it has readers.56

Finally, while having a methodology that allowed for multiple moments of reflection aided the understanding of the work, a key challenge with the methodology is how to take it and apply it within day-to-day practice. The ability to develop and test this methodology was supported by Tate as an organisation, the funding of the Reshaping the Collectible project and the framework of the research, which allowed researchers and practitioners to devote themselves to studying and activating Ten Years Alive. The results obtained through this experiment therefore show the importance of having dedicated collection care-focused projects in institutions, not only to develop practice, but to create sustainable models for future engagement with artworks and the people who are part of their lives. To ensure that this learning can be translated effectively into practice, we have written a simplified methodology based on the one described here, and made it available within this publication.57 This simplified methodology is designed to be scaled to the available resources within a given setting or institution, including both staffing and financial, and will hopefully provide a useful foundation for others in reactivating complex performance artworks such as Ten Years Alive on the Infinite Plain.