O Ubbiri, who wails in the wood

O Jiva! Dear daughter!

Return to your senses. In this charnel field

Innumerable daughters, once as full of life as Jiva,

Are burnt. Which of them do you mourn?

‘Ubbiri’, 6th century BC1

Sheba Chhachhi’s Seven Lives and a Dream is a series of nineteen black and white photographs taken between 1980 and 1991 that depict seven women activists who were at the heart of New Delhi’s fervent anti-dowry protests during that time. The series comprises two sets of images – the first taken at the site of the protests, and the second created collaboratively with some of the demonstrators in a range of public and domestic settings of relative privacy. The images captured amid the protests show women shouting slogans, performing street theatre, or simply being present in solidarity with their fellow activists and bearing witness to the mounting force of the public movement. As demonstrations continued, however, Chhachhi became deeply troubled when she discovered that mainstream journalists were asking women to pose for their photographs in ways that mirrored her compositions, fuelling her growing concerns about the limitations of the documentary genre and its claim to objectivity and truth.2 In seeking to convey a more nuanced and complex portrait of these women she knew so intimately, Chhachhi embarked on a series of staged portraits with seven protagonists of the movement. The process of collaboratively staging each image – the result of weeks or months of experimentation – involved the often elaborate arrangement of props in distinctive environments across Delhi, all chosen by the subjects. The resulting images offer affectively dense portraits that convey their subjects’ diverse class backgrounds, private histories and unique personal stakes in the women’s activist movement.

The depth and complexity of these images is contingent upon the multiple temporal registers that are invoked and encoded in each portrait. In this essay, I approach this proposition from two angles. First, I situate the images within a broader history of Indian photography, focusing specifically on three modes of practice: post-Independence-era photojournalism, ethnographic imagery and the studio portrait tradition. I trace how Chhachhi’s practice transitioned from a documentary paradigm to a more collaborative and performative practice modelled on the subversion of motifs associated with nineteenth-century ethnographic and staged studio portraits, imbuing her contemporary images with traces of fraught historical inheritance. I then shift to a consideration of how the extended duration and complexity of personal histories are articulated in the images. In particular, I argue that the reduplication of photographic images within the portraits opens up a mode of temporal mise en abyme that is key to my reading of this work. The portraits that comprise Seven Lives and a Dream (hereafter Seven Lives) draw attention to how time is layered and looped within the subjective biography of each sitter. Through an archaeology of the palimpsestic nature of these images, I will argue that presence is not grounded in the present alone, but rather iterated through multiple instants and instances of personal and historical meaning.

Contexts for Seven Lives

Let us begin by examining the historical context in which these photographs were produced. Following her training at the National Institute of Design in Ahmedabad, Chhachhi returned to Delhi in 1980 during a period of intense political unrest across India. Indira Gandhi had just returned to power as prime minister following the crumbling of the brief and unstable Janata coalition government that had emerged after the turmoil of the Emergency.3 The country was still reeling from economic instability and had not yet started down the path of economic liberalisation that would usher in major cultural transformation throughout the early years of the 1990s. Social tensions ran high, and change was imminent. The women’s movement in India was a significant development in this era of cultural anxiety and transition.4 In the year of Chhachhi’s arrival, feminist activism was reaching a fever pitch and increasingly powerful networks were mobilised in response to the growing visibility of dowry-related violence.5

The collection of dowry, or payment made from a bride’s family to her husband’s family, had been illegal in India since 1961, but was still widely practiced behind closed doors across the country. In some cases, the husband’s family would torment the bride in order to pressure her into offering up additional goods, and in extreme situations this harassment led to physical abuse or even murder. Death under these circumstances was rarely reported or sufficiently investigated.6

Chhachhi joined the anti-dowry movement as both an active protester and a photographer. As she later explained, ‘I was pointing the camera one moment, and shouting slogans the next’.7 Street demonstrations were complemented by a range of other actions on the part of the women’s movement, such as sit-ins, public testimonies and street plays. Seven Lives includes eight such images, taken between 1980 and 1988; Chhachhi’s personal archive contains many more.

Fig.1

Sheba Chhachhi

Urvashi – Street Play, ‘Om Swaha’, Mehrauli, Delhi 1982, printed 2014, from Seven Lives and a Dream 1980–91

Photograph, gelatin silver print on paper

569 x 380 mm

Tate

© Sheba Chhachhi

Among the most dynamic of these photographs is Urvashi – Street Play, ‘Om Swaha’, Mehrauli, Delhi (fig.1). This image, taken in 1982, documents a performance of the feminist street theatre production Om Swaha, which dramatises the harassment of a young bride at the hands of her in-laws, covetous of receiving a larger dowry. In this image, we see a woman straining against a band of cloth with which her body appears to be forcibly restrained. While the play’s audiences were often dominated by women, here Chhachhi has intensified the claustrophobic vulnerability of the young woman by shooting her anguish against the backdrop of a sea of male eyes.

The (in)decisive moment in Indian photojournalism

It is important at this juncture to situate the immediacy of an image such as Urvashi – Street Play in relation to canonical traditions of photojournalism and documentary photography in India. French photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson, who did some of his best-known work in South Asia, famously theorised such photographic practice in his 1952 text The Decisive Moment.8 The book’s French title, ‘Images à la sauvette’ or ‘images taken furtively/in haste’, offers insight into Cartier-Bresson’s strategy for capturing the ‘precise and transitory instant’.9 He always attempted to blend into his environment, preferring to work alone with a small 35 mm camera and dressed in drab shades. This was not because Cartier-Bresson hoped to go entirely undetected, but rather because he preferred to be unobtrusively ‘caught up in the event’.10 Brandishing his camera, he traversed the world, ‘shooting’ his subjects at the precise instant that he felt could encapsulate the full drama of their situation.

India played a special role in Cartier-Bresson’s career. He first travelled to the newly independent nation in 1948 to photograph Mahatma Gandhi breaking his hunger strike. Hours after he took pictures of Gandhi, the Mahatma was assassinated, and Cartier-Bresson found himself poised, camera in hand, at the epicentre of one of the twentieth century’s most iconic moments. Cartier-Bresson not only created memorable impressions of India abroad, but left a lasting impact on the artistic landscape of the country as evinced by his correspondence with figures such as the artists Satyajit Ray and Jamini Roy.11 He also played a major role in shaping the early careers of Indian photographers such as Raghubir Singh, who grew up with Cartier-Bresson’s book of Indian photographs in his family home,12 and Raghu Rai, who was the first Indian photographer to join the Magnum photographic agency following Cartier-Bresson’s nomination.

Fig.2

Homai Vyarawalla

Rehana Mogul and Mani Turner in a Sculpture Class at the J.J. School of the Arts, Bombay late 1930s

Black and white photograph

Alkazi Collection of Photography, New Delhi

© Homai Vyarawalla Archive/Alkazi Collection of Photography

While Cartier-Bresson’s images of post-Independence India enjoyed wide renown through global circulation, they were no more iconic than the photographs by India’s first major female photojournalist, Homai Vyarawalla.13 Vyarawalla learned photography from her husband in the 1930s and gained prominence as a journalist after moving to Delhi, photographing figures such as Ho Chi Minh, the Dalai Lama, Queen Elizabeth II, and John F. and Jacqueline Kennedy. Before capturing such political celebrities, however, Vyarawalla used her female art-school classmates as subjects, producing an early set of staged photographs that foreshadow Seven Lives in their combination of intimate familiarity and theatrical flair. Consider, for instance, her photograph Rehana Mogul and Mani Turner in a Sculpture Class at the J.J. School of the Arts, Bombay, taken in the late 1930s (fig.2). This photograph presents two young female artists at work in a sculpture studio, both lost in concentrated absorption in the nearly nude male forms above them. One of these male figures is a nearly complete sculpture, while the second figure, appearing slightly further back and therefore blurred by contrast, is a living male model. The textural detail of the sculpture and its privileged position at the centre of the composition suggest an inverted valuation of the hierarchy between model and copy. However, the picture does not unequivocally suggest the superiority of artistic representation over lived reality. Of the four figures present in the scene, the most charismatic figure by far is the artist Rehana Mogul, caught gazing up at her sculptural creation in rapturous profile. It is the artist at work rather than the work itself that is celebrated here – a point driven home by Mogul’s arresting beauty. Historian of photography Sabeena Gadihoke suggests that ‘the image is a powerful one as it reverses the traditional expectations of who gazes at whom in art’.14 I would agree, but not necessarily with the implication that it is the male gaze that is reversed. While the male form is certainly objectified, a viewer does not necessarily focus their gaze on the male body in the photograph, but rather on the form of the artist – the woman as creator rather than as the object of desire.

The fact that the composition is superficially symmetrical, but not quite, makes Vyarawalla’s picture particularly interesting. The sculpture and its model strike identical poses, as if duplicated, with the double transposed a few centimetres above. Mogul is posed reaching up to the right as if at work on her sculpture. The other artist, Mani Turner, bends down curiously to the left as if ‘working on’ the real man with some kind of tool. What could she possibly be doing? The mystery of her action feeds the suspicion that this image was staged in a particularly dynamic tableau. Indeed, these compositional parallels appear almost too striking to have been spontaneous.

We know from other images from this early period that Vyarawalla was adept at staging her photographs.15 Yet as her focus shifted from her art school friends to figures of the cultural and political elite, her approach to image making changed. Indeed, her attitude as a news journalist closely mirrored the position Cartier-Bresson expressed in The Decisive Moment. She explained:

I have never asked anyone to pose for me. I don’t like it, because the moment the subjects know that they are being photographed, a change comes over their countenance. The whole atmosphere changes. The body becomes stiff and the eyes open up a bit, which is not natural. When you take a picture, it’s always in a split second. You either take it or miss it and that must be the right moment.16

Unlike Cartier-Bresson, Vyarawalla did not seek to meld seamlessly into the backdrop. She leveraged her unique profile as a female photographer to attract attention at just that ‘right moment’, and benefitted from the rapport she developed over many years in the press corps with major political figures such as Jawaharlal Nehru.17 Vyarawalla’s distinctly embodied practice, socially embedded in her milieu, was thus critical to her success.

The women’s movement through Chhachhi’s lens

Chhachhi’s early images can be framed within this broader tradition of documentary photojournalism in India, but also diverged significantly from such paradigms. The composition of a photograph such as Urvashi – Street Play shows an impeccable sense of timing; however, Chhachhi’s aims were wholly different to those of such predecessors as Cartier-Bresson and Vyarawalla. Indeed, Chhachhi did not even intend her images for press circulation, but rather as private records for the women themselves. As she explained:

It was internal documentation; it was really for ourselves … Circulation was not at all in the press or mainstream media … A lot of the work of the movement was not simply protesting and taking up issues and campaigns, it was also consciousness-raising in communities, or meeting groups of women and sharing these images with them, as a kind of alternative initiative.18

Chhachhi intended her photographs to offer a broader means of visualising women’s empowerment within the Indian context through highly personal images. Her ‘documentary impulse’ was thus relational from the start.

Fig.3

Sheba Chhachhi

Shahjahan Apa – International Women’s Day Gathering, Dakshinpuri, Delhi 1980, printed 2014, from Seven Lives and a Dream 1980–91

Photograph, gelatin silver print on paper

380 × 567 mm

Tate

© Sheba Chhachhi

Fig.4

Sheba Chhachhi

Shahjahan Apa – Anti Dowry Public Testimonies, India Gate, Delhi 1986, printed 2014, from Seven Lives and a Dream 1980–91

Photograph, gelatin silver print on paper

381 x 568 mm

Tate

© Sheba Chhachhi

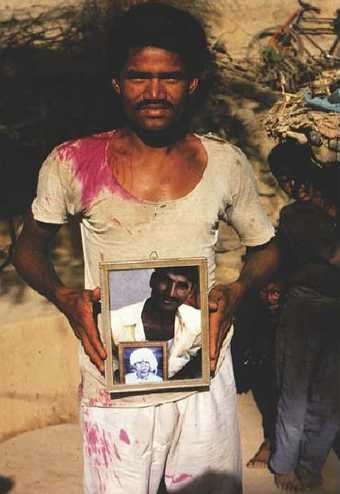

Chhachhi’s deeply embedded perspective from within the movement is evident in the range of protest images included in the Seven Lives series. While many images show the fervour of a crowd, Chhachhi also includes more intimate shots taken in moments of relative introspection, such as Shahjahan Apa – International Women’s Day Gathering, Dakshinpuri, Delhi (fig.3), which captures the mother of a young victim of dowry violence in a close profile shot, gazing calmly ahead while listening to a fellow activist close by her side. A third image, Shahjahan Apa – Anti Dowry Public Testimonies, India Gate, Delhi (fig.4), shows the same woman holding up the image of her murdered daughter. We imagine she is speaking to a crowd, but Chhachhi’s photograph isolates Shahjahan as a figure of resolve, emphasising her prowess through a low angle that positions both photographer and viewer as members of her rapt audience.

Fig.5

Sheba Chhachhi

Sathyarani – Anti Dowry Demonstration, Delhi 1980, printed 2014, from Seven Lives and a Dream 1980–91

Photograph, gelatin silver print on paper

386 x 567 mm

Tate

© Sheba Chhachhi

Many of the crowd-oriented images in Seven Lives focus the viewer’s attention on the individual rather than the collective in this way. This is especially true in the case of what may well be the series’ most iconic photograph, Sathyarani – Anti Dowry Demonstration, Delhi from 1980 (fig.5). This image features another mother who lost her daughter to a dowry-motivated murder. Like Shahjahan, Sathyarani holds up her daughter Shashi Bala’s picture as an expression of rage and pain at what has been taken from her. The viewer’s attention is immediately drawn to the tranquil face of Sathyarani’s daughter, gazing out of the photograph that was taken on her graduation day. While Chhachhi has succeeded in forging an image that captures the dynamism of a movement, she also offers an intimate double portrait of two individuals, a mother and her daughter, that is suggestive of the relationship between them. The unusual effect of a photograph within a photograph – suturing multiple moments in time effectively within a single image – is one that Chhachhi would go on to explore and develop as her engagement with her subjects deepened.

As Chhachhi’s photographic involvement with the women’s movement evolved, however, she became increasingly troubled by common assumptions regarding street photography’s evidential infallibility. Her training had made her all too aware that photographers operate from a position of relative power, and cannot help but bring their unique agenda and perspective to bear on the images they create. Yet she was also conscious that photographic imagery was all too often consumed uncritically by viewers. In addition, she began to notice that mainstream journalists were appropriating her imagery and mimicking her compositions, resulting in the proliferation of superficial coverage of the movement. As she described her predicament:

I began to really question the documentary mode itself. The image of this sort of militant woman, which I was very invested in – it had been a really important and significant image … countering prevalent stereotypes of women as victims or beauties, that image had itself turned into a stereotype. It became a sort of ready vocabulary. I remember turning up at a demonstration and finding the press photographers there, all of them making the women pose – it was like mirroring my photographs. It was a very bizarre moment.19

Chhachhi’s experience further increased her sensitivity to the role that the mass media has in reducing subjects and images to mere stereotypes. While her work had helped expand the representational boundaries of Indian women beyond icons of passive beauty or ethnographic curiosity, she also felt that the production and circulation of the militant woman as a new stereotype negated the complex personal histories and diverse social backgrounds of the activists she pictured.20 As she later remarked of her early images, ‘While these were friends, fellow travellers, sisters in the movement, the images I had of them actually didn’t, I felt, open up the complexity of who they were. And I knew them so much more intimately than what the images spoke of.’21 It is not simply that the photographs misled, it was that they flattened. In response, Chhachhi conceived of a way to explore the complexity of these subjectivities through collaboratively staged portraits.

The shift from street photography to staged imagery seen in Seven Lives evolved out of Chhachhi’s growing concerns around the ethics of photojournalistic practice and the power differential between the photographer and her subject. She rejected the militaristic metaphor of ‘shooting’ images as a description of her practice. The experience of seeing her images re-enacted or staged by mainstream journalists even led her to photograph the photographers at work for some time, fascinated by this technology of capture.22 Increasingly, Chhachhi began to question conventional views regarding the inherent authenticity of street photography and the veracity of the ‘decisive moment’. Instead, she sought to pursue another kind of truth grounded in her subjects’ performativity as well as a heightened transparency about her own subjectivity as a photographer.

Staged portraits: Historical precedents

For this second set of photographs that make up Seven Lives, completed between 1990 and 1991, Chhachhi approached eight of the activists she had become particularly close to over the course of the previous decade, and proposed staging portraits in response to how each woman wished to be portrayed. All the women agreed to participate, but in the case of one subject, the portrait never quite came together.23 The mention of ‘a dream’ in the project’s title refers both to the women’s collective dream of emancipation and the ‘shadow’ woman whose portrait was not included. Chhachhi worked with the other seven women for nearly three months to understand what aspects of their personal experience and life story they most wanted to express as well as how this could be best communicated.24

Chhachhi’s series not only grew out of the personal biographies of her subjects, but also drew on the fraught history of photographic representation within India. In particular, the artist engaged the studio portrait tradition, which emerged as the dominant mode of practice almost immediately after photography reached India in 1839, just months after its public announcement in Europe.25 Nineteenth-century studio photography took many forms, but can broadly be divided into two major categories: ‘ethnographic’-type images and formal portraits. Chhachhi drew on both idioms, bending aspects of their visual vocabulary to produce very different portraits of her protagonists. While the imagery produced by her nineteenth-century predecessors was orchestrated to advertise personal or imperial power along schematic lines, Chhachhi’s photographs were staged to offer insight into the complexities of individual women’s lives.

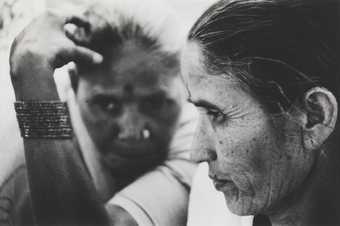

Fig.6

G. Western

A Sannyasi c.1860

Photograph, albumen print

Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of Cambridge, Cambridge

Nineteenth-century ‘ethnographic’ images have been widely discussed as exemplary of the colonial agenda of surveillance and control through the creation of pseudo-scientific taxonomies. As anthropologist Arjun Appadurai put it: ‘Colonial photographic practices, at least where human subjects were involved, allowed the documentary realism of the token (the particular person or group being photographed) to be absorbed into the fiction of the general “type”, most often an ethnological type’.26 These practices were embraced with fervour by amateurs and professionals alike, spanning colonised regions across the globe.27 It is unlikely, however, that any region produced a greater number or variety of ‘ethnographic’ images than India. Such photographic projects were initially motivated in part by humanistic curiosity on the part of the European colonisers. For instance, art historian and anthropologist Christopher Pinney points to G. Western’s albumen print of ‘a Sannyasi’ (religious ascetic; fig.6) as an example of portraiture that might be seen as having more in common with nineteenth-century French studio photographer Nadar’s acutely psychological portraits of celebrities than the static images taken by Western’s contemporaries in India.28 By and large, however, as photographic practice proliferated in India following the 1857 Indian Rebellion, such ethnographic projects tended to become increasingly politicised and the visual vocabulary for image production became progressively schematised and constrained.29

Paramount among the signifiers of group identity in these photographs were each subject’s ‘typical’ costume, the environment in which they were photographed and the props with which they were posed. The photographer often attempted to index the geographical location that was ‘native’ to the subject through a carefully chosen backdrop – either outdoors, constructed in a studio setting, or even added after the fact through compound printing from separate negatives. Props were deployed to even greater effect, used primarily to suggest the individuals’ occupation or caste affiliation. The aim was to use the costumes, environment and props as indexes of group identity, rather than to produce portraits of singular subjects.

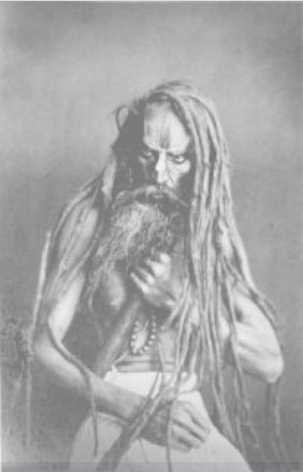

Fig.7

Kharavas, from William Johnson, The Oriental Races and Tribes, Residents and Visitors of Bombay, 2 vols., London 1863–6, vol.1, p.75, pl. no.17

These three elements are clearly illustrated in the two-volume album The Oriental Races and Tribes, Residents and Visitors of Bombay (1863–6), compiled by William Johnson, one of the founding members of the Photographic Society of Bengal.30 Consider, for instance, the staged photograph of the Kharavas (fig.7), along with its accompanying text:

The Kharavas are a clan of Kolis from Gujarat, deriving their name from Kharo, salt, in the making of which they engage themselves in their native country. Many of them are boatmen and fishermen. Within the present century numbers of them have settled in Bombay, where they are engaged principally as cultivators (by the hoe, pickaxe, and billhook), and as layers and turners of tiles used in the roofing of houses. Our group represents five of them in their working costume, with some of their implements of labour.31

It is remarkable how directly this description is translated into the visual representation of the Kharava subjects. We see examples of all three of the ‘implements of labour’ mentioned in the text, and a notable uniformity in their ‘working costume’. Apparently, Johnson also sought to visually represent the environmental context ‘typical’ for these subjects, namely their strong association with boats and proximity to the (salt-laden) sea. However, close attention to the image – especially the odd border between the figures’ heads and the deep background – reveals that this scenic harbour setting was the result of combining multiple negatives: one an image of the subjects and the other of the background vista. The fact that Johnson went to such pains to manipulate the final image underlines his commitment to an almost literal correlation between textual and visual representation of the subject at hand in terms of their costumes, props and especially their setting.

Perhaps the most infamous example of the ethnographic impulse in Indian colonial photography is the eight-volume album The People of India, featuring nearly 500 original images that primarily illustrate examples of India’s myriad castes and tribes.32 Published between 1868 and 1875, the work was commissioned by Lord Canning, then Governor-General of India, and his wife Lady Canning, in order to ‘extend our knowledge of our subjects in the east’.33 As Pinney argues: ‘This project is concerned not with individuals but with categories … The concern is almost exclusively with external signs and how these may be read as signifiers of collective behaviour.’34 Yet The People of India was hardly the sort of well-organised taxonomic record one might expect of such a highly politicised endeavour. Photographs were collected from dozens of professional as well as amateur photographers, resulting in a hodgepodge of formats and wide range of image quality. Indeed, the inconsistent nature of the album was acknowledged quite frankly in preface to the first volume, which states:

The photographs were produced without any definite plan, according to local and personal circumstances … In many cases some descriptive account of the tribes represented accompanied the photographs sent from India. These varied greatly in amplitude and value … These sketches do not profess to be more than mere rough notes, suggestive rather than exhaustive, and they make no claim to scientific research or philosophic investigation. But although the work does not aspire to scientific eminence, it is hoped that, in an ethnological point of view, it will not be without interest and value.35

Despite the broadly colonial aims of these albums, the project also paradoxically produced some of the most idiosyncratic images of individual subjects. Consider, for instance, one entry dedicated to the Sikh ‘sect’ or ‘family’ called the Sodhees, who are portrayed using the simplistic and racist prose that characterises much of the book. The text reads: ‘The Sodhees have in general an evil reputation for immorality, intoxication, and infanticide … on some occasions they act as Sikh priests; but they are not esteemed as such, and their dissolute lives prevent them from receiving the respect of the people.’36 What is interesting is that this unsympathetic portrayal does not align with the authors’ positive assessment of the Sodhees’ loyalty to the British – one of the primary attributes that is highlighted by much of the commentary. Indeed, Pinney concluded that as a whole, The People of India ‘is singularly determined by a desire to classify groups by political allegiance’.37 Regarding such political sympathies, the author of the Sodhee text wrote: ‘Their loyalty stood the test of the mutiny of 1857, and their contingents assisted in operations in the field against the rebels’.38

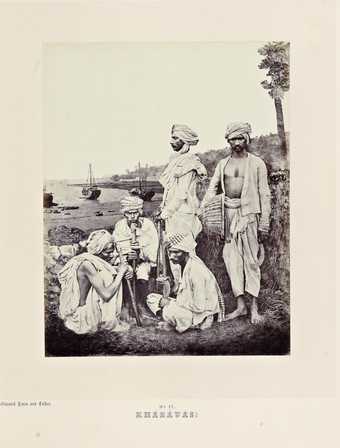

Fig.8

John Forbes Watson and John William Kaye

A Sodhee, Sikh, Lahore, from John Forbes Watson and John William Kaye, The People of India: Races and Tribes of Hindustan, vol.5, London 1872, p.66, pl. no.240

The most unusual aspect of this entry, however, is the individual that has been chosen to stand in for this group. The picture associated with this text shows an elegant man with a long beard sitting erect and cross-legged on a wooden bed (fig.8).39 His turban is lavishly adorned and is affixed with a dangling eye patch. The text explains: ‘He has lost an eye, which is covered by an ornament pendant from his turban; and it is a strange peculiarity of this person, that he dresses himself on all occasions in female apparel.’40 If the intention here were to suggest in this image a recognisable typology, why photograph such a ‘strange’, ‘peculiar’, indeed utterly untypical example?

The inclusion of this figure suggests that the photographers were torn between a desire to represent ethnographic types as an aid to colonial control and the allure of portraying such a striking individual. The photograph’s unusual subject serves as a reminder that the power of a photograph can never be entirely prescribed by the conscious aims of the photographer, be they ideological or artistic. As the philosopher and critic Walter Benjamin remarked of an early image by the photographic studio Hill and Adamson that depicts a woman from a Scottish fishing village (Newhaven Fishwife 1843–7, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York):

With photography … we encounter something new and strange: in Hill’s Newhaven fishwife, her eyes cast down in such indolent, seductive modesty, there remains something that goes beyond testimony to the photographer’s art, something that cannot be silenced, that fills you with an unruly desire to know what her name was, the woman who was alive there, who even now is still real and will never consent to be wholly absorbed in ‘art’.41

Even within the deeply problematic paradigm of ethnographic image making, there exists the echo of a unique subject who could never be entirely subjugated by the photographer’s designs. Chhachhi’s images borrow subtly and subversively from this fraught historical genre of nineteenth-century ethnographic studio productions, and faint but powerful reverberations of its history are refracted in the photographs in Seven Lives. Props, costumes and environment in particular play a central role in the meaning of the staged portraits, and we will now consider how each of these elements function in several images within the series.

Staging agency, intimacy and identity

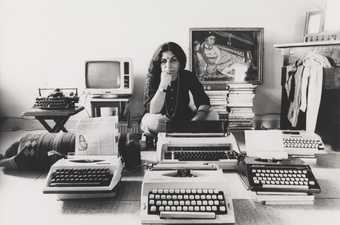

Fig.9

Sheba Chhachhi

Urvashi – Staged Portrait, Gulmohar Park, Delhi 1990, printed 2014, from Seven Lives and a Dream 1980–91

Photograph, gelatin silver print on paper

522 x 783 mm

Tate

© Sheba Chhachhi

Let us begin with Urvashi’s portrait, Urvashi – Staged Portrait, Gulmohar Park, Delhi (fig.9). At the centre of the photograph a striking woman sits cross-legged amid a small army of typewriters. Her chin is resting on her arm, and her kohl-laden eyes are fixed on the viewer above slightly pursed lips. We can tell quite a lot about Urvashi from her commanding pose, which echoes Auguste Rodin’s iconic Thinker 1904 (Musée Rodin, Paris), but suggests a more assertive engagement with the world than his pensive attitude. Urvashi’s identity as a South Asian woman is indexed by the bindi she wears, while the button-down shirt, slacks and wristwatch suggest a casual androgynous cosmopolitanism. It is Urvashi’s setting, however, that does the most to define her in this image – a careful arrangement of ‘props’ within her domestic environment.

The composition is arresting and deceptively simple in its impression of symmetry. The typewriters fan out around Urvashi – those with black keys to her right, those with white keys to her left. The printed photograph of a woman is visible among illegible news columns that emerge from one of the machines, perhaps suggesting the gendered focus of the typewritten text. A rolled-up carpet breaks up the plane of machines, echoing the cylindrical form of the typewriters’ paper-feeding mechanism. A modern computer monitor sits behind Urvashi’s right shoulder, and a traditional Tanjore painting of a reclining semi-nude woman behind her left, suggesting a figure equally at ease with the yap of modernity and the warble of the past. Both the painting and the typewriters are propped up by books – pedestals of knowledge rather than ornaments of display. Each of the typewriters is turned outwards, as if to suggest dialogue, tempering Urvashi’s air of authority with a gesture of invitation extended to the viewer.

It is easy to miss the bureau with clothes tumbling out haphazardly on the right edge of the picture – Urvashi’s collection of silk salwars (traditional trousers). The sensuality of the painting is complemented by the luxury of this cascading silk. One wonders at the choice of disarray in the midst of such an orderly composition. It infuses a jolt of dynamism into what is otherwise a strong if static image, and yet it is tempting to venture a psychological reading as well: this is a woman who has better things to do than pick up laundry. While the bureau establishes the domesticity of the setting, the prominence of the text and typewriters insist upon the space as a site of work and action. Urvashi’s room is not a refuge from the world, but rather a centre from which ideas are developed and disseminated out into it. Thus, the codified divide between public and private spheres that historically played such a central role in the definition of Indian womanhood is summarily disrupted.

The subject of this portrait is Urvashi Butalia, a well-known writer, activist and founder of the feminist publishing house Zubaan in New Delhi. Indeed, the subtle invitation for written collaboration represented by the out-turned typewriters might be read as a reflection of Urvashi’s career and her deep commitment to providing a platform for the narratives of Indian women. Chhachhi’s title for the photograph, however, does not mention its sitter’s last name – as is the case with all of the women she photographed for Seven Lives. What is the reason for this omission? Within the ethnographic studio-portrait tradition, the caption was often as significant as the image itself, ‘textualising’ the photograph to guide the viewer’s interpretation. The same could be said of Chhachhi’s title, although paradoxically her intention can be gleaned from the omission of Urvashi’s last name rather than its inclusion. Urvashi was one of the more publicly prominent faces of the women’s movement, and giving the picture her full name would have drawn attention to this iconicity. By referring to her by first name alone Chhachhi has set up an equivalence with the other activists in the series, some of whom come from markedly more humble backgrounds and have led less public lives.

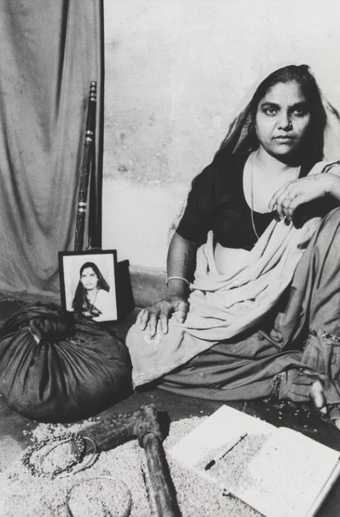

Fig.10

Sheba Chhachhi

Shanti – Staged Portrait, Dakshinpuri, Delhi 1991, printed 2014, from Seven Lives and a Dream 1980–91

Photograph, gelatin silver print on paper

777 x 517 mm

Tate

© Sheba Chhachhi

Such was the case for two other women in the series, Shanti and Devikripa, who both also elected to be photographed in their homes and chose to highlight the activity of writing in their pictures. Shanti’s staged portrait shows the subject seated on the floor with a notebook and pen at her feet (fig.10). She is dressed in a plain ghagra (long skirt) with a loose wrap, which is traditional garb from Rajasthan, the north Indian state that she and her husband left as migrants to seek work in Delhi. Grain is scattered across the floor and into the creases of a notebook before her, along with a couple of Rajasthani anklets, an axe and a bundle of cloth like those carried by poor migrants. Shanti also includes a framed photograph of herself as a younger woman, before her husband passed away in an accident. As a widow, she no longer wears the bindi we see in the framed picture. We will soon return to the significance of this image within an image, which so explicitly reiterates Shanti’s past as constitutive of her present self.

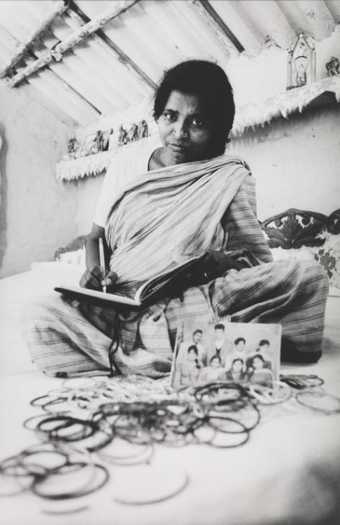

Fig.11

Sheba Chhachhi

Devikripa – Staged Portrait, Seemapuri, Delhi 1990, printed 2014, from Seven Lives and a Dream 1980–91

Photograph, gelatin silver print on paper

769 x 515 mm

Tate

© Sheba Chhachhi

The significance of writing is even further highlighted in the portrait of Devikripa, which actually shows her in the act, with pen to paper (fig.11). She is cross-legged on a broad bed, and meets the viewer’s gaze with an imploring sincerity as she writes in the notebook cradled in her lap. Such an emphasis on literacy and literary agency would have been exceedingly rare in the gendered context of these latter two women’s milieu, and I know of virtually no contemporary precedents for its visual manifestation, photographic or otherwise.

Writing has multivalent significance in the context of these photographs. Most directly, the prominence of writing insists upon the agency of authorship that defines each woman’s relationship with her world. Across class lines, these women are bearing testimony to the systemic injustices that unite them. At a more subliminal level, the prevalence of writing offers guidance to the viewer, suggesting that these images themselves be ‘read’. Reading is a far slower and more engaged mode of consumption than mere seeing. Each photograph was taken in a fraction of a second, and could be registered visibly in as short a time. However, to decode each carefully composed aspect of the staged images requires a different and differently durational mode of engagement.

Although echoes of the form of the ‘ethnographic’ studio portrait might be distinctly recognisable in these images, the communicative effect could hardly be more distinct. There is certainly an ‘exhibitionary’ feel to Chhachhi’s staged photographs, as each subject is clearly and explicitly positioning both their possessions and their bodies in an attitude of display. However, the effect is not one of confining subjects within the sort of objective (and objectifying) narrative that motivated colonial ethnographic projects.42 Rather, the forms of the historical genre of the nineteenth-century studio portrait have been repurposed by Chhachhi in an act of reiterative resistance to essentialising representational regimes.

Nineteenth-century photography in India was not merely used to support dehumanising ethnographic taxonomies; it was also enthusiastically embraced as a medium for portraiture that celebrated the power, elegance and status of those wealthy enough to commission it. By the 1870s, hundreds of studios had sprouted up around the country to satisfy the vanity of India’s elites in the form of photographic cabinet cards and cartes de visite.43 Like the ethnographic images discussed earlier, many of the portraits that such studios produced were highly conventional. The subject would pose amid elegant surroundings of a typically Victorian flavour intended to convey their education, taste and cosmopolitan milieu. Often an ornate piece of furniture would be featured, and such scenes were almost inevitably staged in front of a romantic canvas backdrop suggesting the interior of a drawing room or perhaps a view opening out into a formal garden.

Pinney has discussed these compositional clichés in relation to the European genre of the ‘swagger portrait’ that was common in British art from the seventeenth to the twentieth centuries. This genre has been described by art historian Andrew Wilton as a mode of representation that ‘puts public display before the more private values of personality and domesticity’.44 As was the case in ethnographic photography, props, setting and costume played a leading role in such images. But rather than including objects that conveyed caste or occupation, in the case of these elite portraits the items were self-selected to communicate education, wealth, and in some cases military valour. Books were among the most popular stage props, as were vases with flower arrangements. Men typically displayed ceremonial swords.45 Although such images were not intended as illustrations or aids to colonial surveillance or control, they nonetheless succeeded not so much in conveying the individual personality of their subjects as indexing their subjects’ claims to elite cross-cultural class associations, and thus functioned as no less a token of a well-established type.

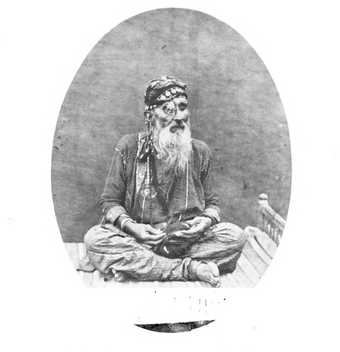

Fig.12

Ram Singh II

Self-Portrait c.1870

Black and white photograph

Maharaja Sawai Man Singh II Museum Trust, Jaipur

A notable counterexample to this homogeneity, however, might be seen in the oeuvre of Ram Singh II, Maharaja of Jaipur (1834–1880). Known as the ‘photographer prince’, Ram Singh was an avid and accomplished amateur photographer in the early days of the medium. His subjects were diverse, ranging from outdoor compositions of wrestlers and cityscapes to elegant studio portraits of courtiers, faqirs (ascetics) and – most remarkable for his time considering the local conventions around purdah (veiling and seclusion) – women in his harem.46 However, the Maharaja’s favourite subject was undoubtedly himself. Many of his self-portraits closely adhered to the Victorian conventions of the genre – regal garments, an elaborate chair and books are all on display. Other self-portraits, however, show a remarkable originality of conception and experimental flair. In one such image he levels his penetrating gaze at the camera’s lens from an elaborately brocaded royal throne (fig.12). Arrayed before him lie a sword and brilliantly burnished shield, and his person is decked out with all the finery befitting his royal lineage. The explicitly local, indigenous identity of this Rajput ruler is further highlighted through the selection of a hanging backdrop. Rather than posing in front of a painted scene of a Westernised palace or drawing room, Ram Singh has chosen a rich brocade that frames his head with an illusionistic nimbus. This trompe l’oeil establishes an instantly recognisable link to the local miniature painting tradition that had been used for centuries to commemorate Ram Singh’s royal predecessors, each of whom were represented within their own golden halos.

Fig.13

Ram Singh II

Self-Portrait as a Shiva Bhakt c.1870

Black and white photograph

Dimensions unknown

Maharaja Sawai Man Singh II Museum Trust, Jaipur

However, Ram Singh was not content only to be pictured as a cosmopolitan dandy or Rajput prince. Another portrait shows him in the guise of a Hindu holy man gazing out of an open window (fig.13). His bare chest and arms are smeared with ash, and before him is arrayed the accoutrements of prayer – a bell, a pot for preparing offerings, and most curiously a small mirror or perhaps an image whose form is obscured by light glancing off its reflective surface. Despite the theatricality and artifice of the staging, this is a portrait of real psychological depth. The Maharaja’s gaze out of the window, beyond the frame as it were, suggests at once a striking presence and interiority as well as an otherworldly remove not entirely dissimilar to Western’s slightly earlier Sannyasi portrait (fig.6).

Pinney argues that the ‘intimate theatricality’ of this image derives in part from the collaborative circumstances that produced it. Ram Singh’s photographic mentor was the Jaipur official court photographer T. Murray, who was also the principal of the Maharaja’s newly formed School of Art. Ram Singh likely composed his self-portrait, but would have needed someone (probably Murray) to help him capture the final image. Pinney writes: ‘In this image, jointly constructed by Ram Singh and Murray, photography does not seek to impose a category of identity plucked from a pre-existing structure but emerges rather as a creative space in which new aspirant identities and personae can be conjured.’47 Perhaps the experimental and heterodox nature of Ram Singh’s self-presentation was in part motivated by the collaborative formation of the image in which it was expressed. After all, self-expression is mute without a witness. Might Chhachhi’s far more involved collaborative photographic practice offer traces of such early instances of complex subjective expression, born out of the nineteenth-century collaboration between a photographer and a king?

Fig.14

Sheba Chhachhi

Radha – Staged Portrait, Anandlok, Delhi 1991, printed 2014, from Seven Lives and a Dream 1980–91

Photograph, gelatin silver print on paper

777 x 517 mm

Tate

© Sheba Chhachhi

The legacy of the ‘swagger portrait’ in Seven Lives might be most strikingly identified in Radha’s portrait, which is staged with a decisively feminist twist (fig.14). The subject is Radha Kumar, an academic and author who, like Urvashi, would have been well known in intellectual circles at the time the photograph was taken. Sporting a fashionable short haircut and sari, she appears both stylish and relaxed, reclining on a chaise longue. With her right hand she appears to stub out a cigarette, and her left foot sports a somewhat incongruous boot. What is most remarkable about Radha, however, is her coy and beautiful smile. Unlike the other women in Seven Lives, Radha’s face does not radiate solemn resolve so much as engaged and even playful delight. Activists may indeed be glamorous as well as grave.

The portrait is animated by a strong diagonal composition that can almost be divided in three distinct bands running from the top left to the bottom right, with Radha’s reclining form occupying the centre. Behind her are two somewhat precarious towers of books. This is an appropriately imposing backdrop for such an esteemed woman of letters, who two years after the making of this portrait would publish The History of Doing, one of the definitive historical accounts of the women’s movement in India.48 In the foreground are three framed photographs of a girl, a gentleman in a suit and a young woman with a radiant smile. As in the images of Shanti and Devikripa discussed earlier, the presence of these photographs underlines the significance of familial ties in a portrait of an otherwise remarkably independently minded individual.

My argument thus far has focused on how Chhachhi has drawn upon photographic precedents established in nineteenth-century Indian studios in ways that subvert the formal logic of their original intent in favour of illustrating the unique personal and political subjectivity of her subjects. She is unequivocally establishing a visual vocabulary wherein the Indian woman activist is made visible, albeit not typologised. The selection of each subject was motivated by their membership in this ‘sisterhood’, and like the occupations displayed in nineteenth-century studio portraits, the commitment to the women’s movement defines who these women are through what they believe in and do.

Photographs within photographs: Temporal mise en abyme

I will now turn to the most semantically complex ‘prop’ featured in many of Chhachhi’s images: the framed photograph. The existence of the image within an image is a recurring motif in Seven Lives that anchors the viewer’s attention and offers a key to understanding the unique semiotic richness that the photographs in the series convey. The prominence of these pictures within pictures signals not only Chhachhi’s investment in her subjects’ personal histories, but also registers her own artistic investment in histories of photographic practice in South Asia.

What we see here is an effect that might be likened to the ‘mise en abyme’, a term first coined by André Gide to describe a trope in his own writing, and more recently developed in relationship to photography by Craig Owens.49 The phrase, meaning ‘to put into the abyss’, describes an aesthetic condition in which a work contains its own representation, thus at least threatening the ‘infinite regress’ that the original French implies. Gide adopted this term from a motif in heraldry in which a coat of arms includes within it a smaller representation of itself. While this relationship suggests the possibility of infinite regress, Gide used the term somewhat more generally, as in his example of the mirrored viewer in Diego Velázquez’s Las Meninas 1856 (Museo del Prado, Madrid).50

Fig.15

Christopher Pinney

Ramlal holding a portrait of his brother Hira holding a portrait of their father, Bhatisuda, Madhya Pradesh, 1997

Reproduced in Christopher Pinney, Camera Indica: The Social Life of Indian Photographs, Chicago 1997, fig. no.100

© Christopher Pinney

Although Owens explored the implications of the mise en abyme effect in the context of European avant-garde traditions, such as the photography of Brassaï, this effect is also in evidence across South Asian art historical traditions. Mughal miniatures, for example, often depict paintings within paintings (within paintings) as a means of directing the viewer’s attention to the status of the artist or the nature of representation itself. Indeed, there are parallel examples grounded in India’s vernacular photographic tradition. Based on his extended research in the Indian village of Bhatisuda in central India in the 1980s and 1990s, Christopher Pinney offers a comprehensive analysis of a series of images he discovered (and had a hand in making) in the house of a widow named Kesarbai. The photograph in question shows Kesarbai’s son Hira holding a black and white portrait of his deceased father Ganpat. Pinney also reproduces another image that he was asked to take, which shows Hira’s brother Ramlal holding the portrait of Hira holding their father’s portrait, thus tripling the photographic presence in a single frame (fig.15). As Pinney reflects:

There is a powerful notion here of the translatability of an affective to a special proximity through re-photography, through a sort of recursive binding in of space, a representational involution, as though this photographic recuperation was capable of arresting time itself.51

A similar doubling of photographic imagery is a striking feature of several photographs included in Seven Lives. All but one of the staged portraits include other photographs, and many of these pictures within pictures are previous images taken of the sitter. Indeed, in several images, the photographs within photographs of the subject were taken by Chhachhi herself, further highlighting the significance of the staged reduplication. Drawing on both the linguistics of Roman Jakobson and structuralist anthropological accounts of Claude Lévi Strauss, Owens makes the point that reduplication is fundamentally distinct from mere duplication, and is of a semantically significant status because of the extended and intentional self-referentiality of the gesture.52 If one is convinced by Owens’s argument then there is every reason to believe that the communicative force of Chhachhi’s images might be most powerfully anchored in the instances they present of photographic mise en abyme.

Fig.16

Sheba Chhachhi

Shahjahan Apa – Staged Portrait, Nangloi, Delhi 1991, printed 2014, from Seven Lives and a Dream 1980–91

Photograph, gelatin silver print on paper

785 x 521 mm

Tate

© Sheba Chhachhi

As if to drive the point home, Chhachhi’s reduplication is itself reduplicated through her insistence that multiple images of the same woman must be displayed at one time. As part of Chhachhi’s arrangement with Tate, the artist agreed that the photographs may be shown in multiple configurations so long as all the images clustered around a single subject are shown together.53 Thus, Chhachhi’s image of Shahjahan Apa at India Gate (fig.4), which contains a photograph of Shahjahan’s daughter, is displayed alongside Shajahan Apa – Staged Portrait, Nangoli, Delhi (fig.16), which includes the earlier picture taken at India Gate. The form of the display itself then mirrors the recursivity of the photographic image. For Owens, this kind of effect demonstrates how photography can reflect back on its own conditions of meaning making: how photography can say something fundamental about the medium of photography. I would argue that for Chhachhi this effect also allows her to say something fundamental about her own subjects.

Consider how this photographic mise en abyme functions in the portraits of Sathyarani and Shahjahan Apa, two activists for whom the movement was arguably the most personal given that they both lost their own daughters to dowry-related murders. Shahjahan Apa’s portrait features a gaunt and solemn figure seated cross-legged on a bed (see fig.16). Her right hand holds a length of dark fabric, a burka, that drapes across her knees and over the left hand, which is positioned in a sort of mudra, a ritual hand gesture used in several Indian religions and codified in the iconography of subcontinental sculpture.54 By her side, a small model house rests on the bed. A shelf behind her displays neatly stacked cups, plates and bowls, a radio, a sewing machine and a calendar print of a young boy reading the Koran. The most powerful of the props displayed around Shahjahan Apa, however, are the three photographs prominently centred at the bottom of the frame at her feet.

Let us unpack the semiotic complexity that the reduplication of photographs provides in this portrait, as this function does the most work to offer an alternative to the ‘flatness’ of portrayal that Chhachhi claimed she wanted to move away from. The photographs at the bottom of the composition present Shahjahan as an activist in the public sphere, suggesting that this form of action is central to her identity. This role is accentuated by its contrast with the domesticity of the ‘real’ Shajahan seated on the bed at the centre of her one-room home, the significance of which is signalled mimetically in the form of the small model home next to her. The display of archetypal portraits such as these is ubiquitous in Indian homes, yet their subjects are typically gods, deities or ancestors, with the odd politician and film star thrown in – the picture of the boy reading the Koran above Shahjahan is an example of this. Displaying images of an ordinary woman pictured beyond the realm of her family or marriage is highly unusual. For Shahjahan to be thus portrayed – not only as a woman unaccompanied in public space, but also as a figure in the midst of activist agitation – would have immediately struck contemporary viewers as remarkable indeed. Such a framing suggests that Shahjahan should be considered significant, even revered, for her role in public life.

However, the fact that Shahjahan multiply confronts the viewer in Chhachhi’s staged portrait resists the reification of ‘militant activist’ iconography. As well as an activist, Shahjahan is a private individual whose livelihood is based in her work as a seamstress, as the sewing machines attest. Thus, the domestic setting highlights both her public and her private personae through the contrast between them, hemming together two disparate realms represented by multiple moments in Shahjahan’s life. This image is haunted by another visage as well, and another moment, barely visible but undeniably present – that of Shahjahan’s murdered daughter. Her face is shown in the picture that Shahjahan holds up at the rally, which itself appears at Shahjahan’s feet in the staged portrait, as mentioned above.

Fig.17

Sheba Chhachhi

Sathyarani – Staged Portrait, Punjabi Bagh Residence, Delhi 1990, printed 2014, from Seven Lives and a Dream 1980–91

Photograph, gelatin silver print on paper

382 x 568 mm

Tate

© Sheba Chhachhi

Fig.18

Sheba Chhachhi

Sathyarani – Staged Portrait, Supreme Court, Delhi 1990, printed 2014, from Seven Lives and a Dream 1980–91

Photograph, gelatin silver print on paper

772 x 516 mm

Tate

© Sheba Chhachhi

The ghost of another murdered daughter is present in Seven Lives through the picture of Sathyarani’s daughter Shashi Bala, which is featured in all three of Sathyarani’s portraits. This picture, present in the 1982 protest image of Sathyarani (fig.5), has a pride of place in her subsequent two staged portraits as well – one taken in her Punjabi Bagh residence in Delhi (fig.17) and the other staged on the steps of the Supreme Court (fig.18). The reams of documents splayed out before Sathyarani in these latter two portraits represent just a fraction of the court proceedings she spearheaded in seeking justice on behalf of both her daughter and other dowry violence victims and their families. At the time that these pictures were taken in 1990, she had still found no legal resolution for her own case. She finally won her claim in 2013, but in a bitter twist of events, her daughter’s husband had disappeared and has yet to be located or brought to justice.55

Strikingly, Sathyarani hardly seems to have aged in the decade separating the image of her protesting on the street in 1980 and her staged portraits from 1990. Despite the contrast in her pose – extremely animated in the earlier image and markedly still in the two posed portraits – her silver hair and plump face and body remain virtually unchanged. The protest image and the staged portraits might well have been taken just a day apart. This observation seems to run against the grain of writer Susan Sontag’s claim that:

Through photographs we follow in the most intimate, troubling way the reality of how people age. To look at an old photograph of oneself, of anyone one has known, or of a much photographed public person is to feel, first of all: how much younger I (she, he) was then. Photography is the inventory of mortality.56

Rather, these images appear to evince photography’s seemingly contradictory capacity to collapse time. This phenomenon was perhaps most strikingly observed by Benjamin, who wrote with a near-mystical obscurity: ‘The true picture of the past flits by. The past can be seized only as an image which flashes up at the instant when it can be recognized and is never seen again.’57

However, the effect Chhachhi’s photographs have of collapsing time extends beyond the relatively inconspicuous aging of their subjects. Consider once again the photograph of Shashi Bala on her graduation day. The power of Sathyarani’s daughter’s image surely derives in part from what Benjamin identifies as ‘that tiny spark’ that connects the present to the past in the photographic image. As he writes:

The spectator feels an irresistible compulsion to look for the tiny spark of chance, of the here and now, with which reality has, as it were, seared the character in the picture; to find that imperceptible point at which, in the immediacy of that long-past moment, the future so persuasively inserts itself that, looking back, we may rediscover it.58

It is impossible to entirely abstract Shashi Bala’s fate from this photograph of her graduation. Her future is irrevocably imprinted onto the past in the eyes of the knowing viewer through the medium of Chhachhi’s picture. It is as if Sathyarani desired that her daughter be ‘present’ at the rally – almost as if she were a participant rather than merely an icon or effigy. In the moment that Chhachhi took the photograph of Sathyarani with her arm raised, she was solidifying, as it were, a future past. She thrust Sathyarani into the same temporal limbo as her daughter, both petrified in a moment of power emblemised by a mother’s fist and a daughter’s degree, which collapses the time that divides them.

Despite the reference to an earlier moment, these staged portraits do not operate primarily in a nostalgic register. Rather, they demonstrate something powerful about who Shahjahan and Sathyarani were at the moment their staged portraits were taken – tenacious and resolute women committed to social change. In fact, both women went on to devote their lives to anti-dowry activism, together founding Shakti Shalini, a legal aid and crisis centre for women who, like their daughters, were being tortured within the family. Chhachhi’s portraits suggest that what is technically their past is an essential characteristic of their present. The photographs do not register a temporal divide but rather enact the non-linear disorientation of temporal collapse.

Perhaps this effect can be explained by the very content of the staged portraits. They convey the spirit of women whose lives have, in one profound dimension, reached a standstill. Their struggle for justice persists in a legal system that has required decades of court appearances. The viewer senses in the images that these women refuse to move on, and this resolve is captured as a sort of agelessness that flies in the face of the logic of mortality that Sontag identifies as essential to so many photographic portraits. The staged portraits reify the immediacy and imminence of the past.

Sathyarani’s staged photograph may also call to mind a subset of unusual portraits within the tradition of Mughal miniature painting that feature an emperor holding out another portrait. The (secondary) subject of the portrait within these portraits varies. A painting from c.1614 by Mir Hashim and Abu al-Hasan (Portrait of Emperor Jahangir c.1614; fig.19) shows Emperor Jahangir holding a portrait of his father, Akbar, while another from c.1620 shows Jahangir similarly cradling a picture of the Madonna. A work from 1627 shows a woman – possibly Nur Jahan – holding a portrait of her husband, Emperor Jahangir (Bishandas, Nur Jahan Holding a Portrait of Emperor Jahangir c.1627, Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland). There is even a 1627–8 portrait of Emperor Shah Jahan holding a portrait of himself in the form of a pendant on which he is depicted in miniature (Chitarman, Shah Jahan on a Terrace, Holding a Pendant Set with His Portrait 1627–8, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York). It is the earliest of these examples, however, on which I would like to focus my comparison to the image of Sathyarani holding out her daughter’s portrait.

Fig.19

Mir Hashim and Abu al-Hasan

Portrait of Emperor Jahangir c.1614

Ink, gouache and gold on paper

116 x 83 mm

Musée du Louvre, Paris

The c.1614 portrait of Jahangir holding up a portrait of his father has generally been discussed as either an expression of filial piety or a gesture of revisionist history on the part of the young ruler. Akbar is depicted holding up a globe as if offering it to his son, signaling the peaceful transfer of power from one generation to the next. As art historian Amina Okada has written, ‘the globe was an emblem of temporal power, and Akbar’s gesture of handing it over represents a symbolic legitimization of Jahangir’s accession’.59 Yet the relationship between father and son had hardly been as harmonious as this painting might suggest. In 1600 Jahangir, known then as Prince Salim, had staged an unsuccessful revolt against his father, who was away waging war in the Deccan. Prince Salim established an independent monarchy in the city of Allahabad and killed one of his father’s most trusted ministers, yet son and father eventually reconciled and Akbar named Prince Salim his heir.

The historical revisionism that this portrait suggests in establishing dynastic legitimacy might be seen as intrinsic to the very form of the double portrait. As art historian Gregory Minissale argues:

Jahangir is ‘more real’ than the picture he holds up, another example of contrasting fiction with reality. The fascination with this image lies precisely in the play between one depiction of reality supplanting or superseding another. And yet, there may also be something of the memento mori in this, as Jahangir holds his picture of his dead father as any viewer could hold the painting in question, and if this had been given to his son Shah Jahan, how better to visually conceptualise the waxing and waning of succession?60

This interpretation highlights some fundamental cleavages in the operations of Sathyarani and Jahangir’s (double) portraits, despite their striking formal similarity. As I have been arguing, the presence of Sathyarani’s daughter in the form of her portrait does not render her less real in comparison with her mother, but rather just as real, despite having physically passed away. To the extent that it does operate as a memento mori, Sathyarani’s daughter’s image urgently repudiates the ‘waxing and waning of succession’, both because of the horrifically unnatural cause of death and the perversely inverse relationship between parent and child. It is the child who ought to venerate a parent who has died, not the other way around. This disturbing reversal of the ‘natural order’ is formally mirrored in the inverted physical relationship between the two subjects in each picture. Jahangir gazes into his father’s eyes, emphasising the relational legacy of both regal and familial succession. Sathyarani, by contrast, holds her daughter’s picture out for the world to see, in a powerful gesture of rage and resistance against an act of violence that so flagrantly violated such succession. Indeed, considered from one further level of abstraction, the pictorial inversion of such a venerated Mughal masterpiece might be seen to represent Chhachhi’s own subtle repudiation of both the patriarchal and the elite pictorial traditions of South Asia.

Looking back for the future

We have seen that Seven Lives demonstrates an alternate temporal orientation that I argue lies at the heart of the pictorial power of this series – an orientation that refuses to remain fixed in a single historical instant but rather loops back on itself, refracting meaning across temporal gaps. These are not images that present the spectacle of history framed through a single, decisive moment. Rather, Chhachhi produces a set of pictures that draw together disparate temporal registers and emphasise the essential fluidity of time’s embodied effect.

This essay began with a consideration of how Sathyarani’s iconic portrait might be seen as exemplifying the ‘decisive moment’ celebrated by journalists such as Cartier-Bresson and Vyarawalla. Indeed, the drama of the moment inspired mainstream journalists to restage her ‘militant’ stance, thus paradoxically ‘flattening’ her portrayal in the public eye. Yet there is a seed of resistance to this flattening detectable in Chhachhi’s initial image, visible in the tranquil face of Sathyarani’s daughter.

Drawing from the fraught tradition of studio portraiture in South Asia, in Seven Lives Chhachhi staged a series of portraits in which the presence of the past becomes a central motif through the reduplication of photographic iteration – a mode of temporal mise en abyme. For Owens, the mise en abyme effect was fundamentally physical, or more precisely spatial, the redoubling of the subject signifying photography’s ontological status as an essentially meaningful medium of representation.61 In Seven Lives, however, this effect is deployed to evoke the temporal layering that opens up the complexity of each of the subjects’ lives. One would be hard pressed to think of a better series of images to illustrate one of Roland Barthes’s most oft quoted observations:

The type of consciousness the photograph involves is indeed truly unprecedented, since it establishes not a consciousness of the being-there of the thing … but an awareness of its having-been-there. What we have is a new space-time category: spatial immediacy and temporal anteriority, the photograph being an illogical conjunction of the here-now and the there-then.62

I would argue that Chhachhi’s images extend this temporal consciousness one step even further – as a projection into the future and an imperative for ethical action on the part of the viewer. In the case of Sathyarani’s portrait at the rally, for example, the image of her daughter implores the viewers in the crowd to act in the service of preventing similar atrocities in years to come. Similarly, Chhachhi’s image of Sathyarani holding her daughter’s portrait provokes viewers of the photograph into ethical action beyond the historically grounded context of the anti-dowry protests. This includes viewers far removed from this initial context, such as those who might encounter the photograph on the walls of Tate Modern in twenty-first-century London.63

Coda: Beyond Seven Lives

While Chhachhi’s project was inextricably grounded in its immediate local context, Seven Lives is also imbricated in a broader global discourse around shifting strategies of documentary image making and evolving modes of representing tropes of resistance and protest. One of the artists who has been most influential in contemporary thinking around such images is Allan Sekula, whose writing and photographic practice incisively interrogated assumptions about the documentary genre, beginning in the 1970s.64 Like Chhachhi’s, Sekula’s practice was informed by feminist investments and Marxist critiques of the new left. His critical writing was instrumental in both articulating and breaking down enshrined dichotomies between the socially engaged documentary tradition exemplified by Lewis Hine (1874–1940) on the one hand, and the formalist avant-garde tradition of fine art photography exemplified by Alfred Stieglitz (1864–1946) on the other.65 Sekula argued that both of these approaches, although often understood as essentially at odds, served ultimately the same end of drawing attention away from the photographic subject to the artistic ‘genius’ embodied by the author/photographer. In his own photographic practice, Sekula sought to destabilise such authorial singularity in his repeated efforts to expose the mechanics of global labour relations.

Sekula coined the term ‘anti-photojournalism’, championing a new mode of documentary image making that ran ‘against the grain’ of heroic mainstream approaches to photojournalistic practice.66 Art historian Stephanie Schwartz sets Sekula’s method against the iconicity of Cartier-Bresson’s ‘decisive moment’, arguing that it ‘simply acknowledges what Cartier-Bresson sought to ignore: time. Socialisation, the dialectical relationship between subjects and objects evidenced in Sekula’s photographs, cannot be captured in an instant. It is relational; it takes place over time.’67 Schwartz’s analysis could just as incisively describe Chhachhi’s method and its stark contrast to Cartier-Bresson’s model. Both Sekula and Chhachhi sought to create complex and intimate portraits of their subjects through multiple perspectives developed over time, yet the actual appearance of their images stands in stark contrast. Sekula’s visual style might be characterised as an unmonumental, snap-shot aesthetic (see, for instance Waiting for Tear Gas 1999–2000, Tate), while the portraits in Seven Lives are meticulously staged. Sekula’s images suggest the complexity of the social phenomena they investigate through omission and withholding, while Chhachhi’s pictures offer almost a surfeit of encoded signs. If Sekula’s strategy is more dependent on the multiplicity of images and the experimental combination of image and text, Chhachhi accomplishes a similar effect through a dense layering of meaning within a given image that emerged out of the unique history of studio photography in South Asia.

While Chhachhi has articulated her critical stance against the violent masculine vocabulary of ‘shooting’ a picture,68 her practice might similarly be read as standing up to the more general violence of the canon (or cannon). Following the militaristic mirroring of homophones here, if a subject can be immobilised with a shot, a far greater number can be obviated with a cannon. Given the generally masculine Western foundation of art historical canonisation, Chhachhi’s subjects are precisely those voices most likely to be left out, especially when their representation exceeds the bounds of militant caricatures that are themselves largely grounded in romanticised tropes of resistance. Art theorist Geeta Kapur addressed the broader issue of postcolonial responses to canonisation as follows:

How shall we battle the bogey of the canon? It is not the case that we can add and subtract, participate and deflect: That is nothing more than a kind of graft long associated with postcolonial and postmodern tactics … We must face the canon, then, with the power of contradiction: linguistic, ideological, and historical. With such scrutiny, the canon may become more like a trace that is useful in nothing but laying fresh ground – in the way of a palimpsest – for art-historical discourse.69

As an exemplar of this strategy, Seven Lives should not be read as augmenting a canonical archive of women’s activism in India. Rather, it opens out possibilities for representation through a palimpsestic syntax that captures the social, historical and deeply personal complexity of activist lives.