Not on display

- Artist

- Yves Tanguy 1900–1955

- Original title

- La Journée Bleue

- Medium

- Oil paint on canvas

- Dimensions

- Support: 630 × 812 mm

frame:740 × 950 × 58 mm - Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Accepted by HM Government in lieu of tax on the estate of Cynthia Fraser, Chairman of the Friends of the Tate Gallery 1965-71, and allocated to the Tate Gallery 1996

- Reference

- T07080

Display caption

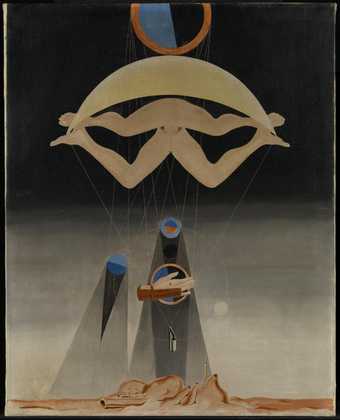

Colourful groups of forms and shapes occupy the foreground of this work. They deny any rational explanation. But they have been associated with the ancient standing stones of Tanguy’s native Brittany in France. Tanguy joined the surrealist movement in 1925, the year after its formation. As a surrealist artist, he was committed to exploring the unconscious mind. Tanguy often depicted vast dream-like spaces, like the one seen here in Azure Day.

Gallery label, August 2020

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Technique and condition

The painting was executed on a single piece of light-weight linen canvas, attached to stretcher with steel tacks. The stretcher is most probably original. The canvas was commercially prepared with a white oil-based primer, probably over a thin layer of animal glue size.

The paint was applied over this priming, in a very controlled and precise manner. First the background space was established with a diluted oil paint, which would have been applied reasonably quickly to ensure the very smooth gradation of colour, from the light blue along the top edge, through white, grey and finally to black at the bottom edge. For any given point on the canvas, the particular colour in the background runs along the whole width of the canvas, i.e. underneath all the objects. These were painted over the background layer after it had completely dried with a thicker oil paint, probably straight form the tube. Despite some very slight areas of impasto corresponding to the brush strokes, these objects are essentially painted in a single additional thin layer.

Although very difficult to see, even under high magnification, the painting is probably varnished with a very thin synthetic varnish. A label on the back of the stretcher reads Tom Learnerplastic varnish

. If present, this coating is unlikely to be original, but since it has not yellowed or cracked at all, there is no need to remove it. The frame is thought to be original to the work and has been recently modified to allow for glazing and the fitting of a backboard, both of which will ensure the optimum level of protection to the painting. The painting is in excellent condition, with a very stable support and no signs of any cracking or discoloration in the paint layers.

October 1997ûûûû

Catalogue entry

Yves Tanguy 1900–1955

Azure Day

La Journée Bleue

1937

Oil paint on canvas

630 x 812 mm

Inscribed ‘YVES TANGUY 37’

Accepted by HM government in lieu of tax on the estate of Cynthia Fraser, Chairman of the Friends of the Tate Gallery 1965–71, and allocated to the Tate Gallery 1996

T07080

Ownership history:

Taken to New York by Pierre Matisse, the artist’s dealer in the 1940s; sold to Robert Fraser, New York in the mid-1950s, from whom passed to Cynthia Fraser, London (Chairman of the Friends of the Tate Gallery 1965–71).

Exhibition history:

References:

Azure Day is typical of the ambiguous landscapes for which Yves Tanguy is known and which, according to his friend and surrealist colleague André Breton (1896–1966), function as concrete representations of the unknown.1 Tanguy’s paintings have often been interpreted as depictions of an unknown planet populated by strange living creatures or ‘Beings’. This is likely to be partly due to his painting process, in which he first created the background setting, before adding the figures on top of it. His first step was to cover the entire linen canvas in oil paint diluted with turpentine. He applied this layer relatively quickly in broad horizontal brushstrokes and blended the paint to create a smooth gradation from black in the foreground, through grey and white in the middle, to a lighter blue haze along the top the canvas. This top section suggests a substance more atmospheric than the arid, desert-like foreground, which is rendered more solid through the dark shadows cast diagonally upon it. Though Tanguy, perhaps under the dominating influence of his friend André Breton, ceased to include an actual horizon line in his paintings in the early 1930s, a pale band in the middle distance of Azure Day hints at a faint vestige of this feature of his earlier works.

Once the initial background layer was dry, Tanguy used a thicker oil paint, possibly straight from the tube in places, to add the biomorphic forms. In the late 1930s, these were increasingly concentrated in the foreground of the picture, and in this respect Azure Day is typical of this period, with its figures situated in the lower half of the canvas, mostly in the bottom right corner. That they appear smaller further up the picture plane implies a sense of space receding into the distance. Gordon Onslow Ford (1912–2003), Tanguy’s artist friend, described how the figures that populated ‘Planet Yves’ were painted: ‘the most simple ones started with a wide contour stroke that ended where it began; a contrasting colour was put in the middle, and the edges between the two were deftly blended – the more complex the Being, the more brush strokes and the more colours used.’2 Many of the forms in Azure Day still bear these dark outlines, moulded with small strokes of white, blended to create a thin, uniform paint layer. In contrast to the muted tones of the landscape, the figures are depicted in bright hues, with yellow, blue and magenta combining to create multi-coloured, composite forms that are lit by an unseen source situated to the lower right hand side of the viewer’s field of vision.

To the right of the picture, where the lighter sections of the large, composite figure meet the fading background, pencil outlines around the figures are visible. Their existence contradicts Tanguy’s insistent claims that he never planned the composition of his paintings or carried out preparatory drawings. In response to a questionnaire on ‘The Creative Process’ published in Art Digest in 1954, he stated: ‘I am incapable of preparing a plan or working from a sketch.’3 This assertion was later echoed by Gordon Onslow Ford in his 1983 tribute Yves Tanguy and Automatism, the title of which emphasised the importance of this spontaneous aspect of surrealism in interpreting Tanguy’s work. ‘When the time was ripe,’ Onslow Ford declared, ‘Beings were born. It was not known where one would appear, or what form it would take, until it appeared.’4 However, the fact that Tanguy did not make greater effort to hide the pencil lines in Azure Day suggests that his claim was as much for the spirit as the reality of automatic artistic production.

Tanguy’s emphasis on the role of the subconscious in his methods reflects the central surrealist concern with automatism as the means by which the inner impulses of the artist might be revealed without being mediated by his conscious impulses. André Breton’s first surrealist manifesto of 1924 called on writers to explore the unconscious by harnessing ‘pure psychic automatism’.5 Early surrealist experiments in automatic writing had given rise to various similar techniques in the visual arts, including André Masson’s (1896–1987) automatic drawings and the ‘frottage’ works of Max Ernst (1891–1976). For Breton, such strategies assured the surrealist painter’s role – and especially Tanguy’s – as a psychic ‘seer’, capable of making concrete the vision of his ‘inner eye’. By 1933, however, he had revised his absolute stance on automatism, and it was acknowledged that it was acceptable to combine it with some level of premeditated artistic intention. More broad attempts to negate the conscious influence of the artist allowed the assimilation into the central body of surrealism a series of works that recorded prior experiences of the unconscious, if not actually resulting from an automatic process.

Painters such as Salvador Dalí (1904–1989), René Magritte (1898–1967) and Paul Delvaux (1897–1994) depicted enigmatic dreamscapes and fantastic subject matter in meticulously realistic technique. Their paintings presented unexpected objects in an illusionistic space in the tradition of their predecessor Giorgio de Chirico (1888–1978), whose work had inspired Tanguy to take up painting in 1923. Works such as Azure Day find notable resonance with this group of surrealist painters, both in their veristic style and their use of this style to create ‘inner landscapes’. The meticulous brushwork in Azure Day is blended so as to be almost undetectable. It points at a shift within Tanguy’s oeuvre, a move away from the expressive sfumato effects of his ‘fumée’ pictures of the late 1920s, in which the paint was applied in a freer, more gestural manner. James Thrall Soby, who curated the retrospective of Tanguy’s work at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, in 1955, described Tanguy as ‘a profound craftsman and an easel painter in the classical sense of the term’.6 He praised Tanguy for the intensity and concentration with which he worked, continuing: ‘his subconscious visions were never scribbled as in the “automatic” images of some of his colleagues, but were communicated with the utmost finesse.’7

Though Tanguy never referred specifically to his formative experiences or influences, the forms that populate the dream-like desert landscape of Azure Day were no doubt partly inspired by the scenery of his childhood; he had spent his early summers in the Tanguy family’s home village of Locronan, in the region of Finistère in Brittany, the westernmost point of France. Later, during the late 1920s, he would return there from Paris with his friends the poet and writer Jacques Prévert (1900–1977) and the musician and writer Maurice Duhamel (1884–1940). The landscape of Finistère is populated by prehistoric menhirs – tall upright standing stones such as the yellow form to the right of the painting – and dolmens – composite megalithic forms which provided inspiration for the more complex of Tanguy’s figures. Locronan’s long Celtic heritage was dominated by legends of immaterial, wandering ‘Beings of the Otherworld’. In his publication on Tanguy in 1946, André Breton made reference to this Celtic heritage, hailing his friend as ‘the guide of the time of the mistletoe Druids’.8 The village was said to be near to the site of the legendary sunken city of Ys, a myth that almost certainly inspired some of Tanguy’s more subaquatic landscapes. Such legends were described in manuscripts that were shown to Tanguy by his bibliophile father, who also conducted research into Celtic megalithic culture and conducted archaeological excavations in the area.9

The ‘Beings’ of such legends no doubt provided inspiration on some level for works like Azure Day. The forms contain shapes that combine elements of the animal, vegetable and mineral classifications, yet still imply living beings: the magenta figure towards the right of the picture resembles the bust of some unknown creature rising from the ground, its jutting form hinting at a horned face peering into the darkness. Next to it, and dominating the foreground of the painting, the more complex composite figure includes a dark hole that suggests an eye and a long yellow form that extends to the ground like a limb. In the middle distance to the left of the canvas, nebulous clouds, a more common feature of Tanguy’s earlier paintings, might be interpreted as the vaporous breath of these beings. However, any interpretation must be tentative. Describing Tanguy’s iconography in 1946, André Breton commented on its deliberate ambiguity and warned against attempts to interpret concrete identities in its forms. ‘Tanguy’, he claimed, ‘is far from regretting the necessity of including some of these “direct” elements in his paintings, as it often happens that they set off the occult meanings of other elements.’10

The unidentifiable, prehistoric forms that inhabit Azure Day fulfil a similar function to that of Tanguy’s self-proclaimed automatism. For the surrealists, the prehistoric spoke of a primal state unconstrained by the conventions of modern perception and representation. ‘The eye’, declared Breton in his 1928 text on Surrealism and Painting, ‘exists in a savage state.’ According to surrealist thought, regression to prehistory mirrors the return to an untrained state of childhood, freeing the unconscious. This notion of a state prior to language is expressed by the terms in which Tanguy’s contemporaries viewed his works, accounts that frequently utilised expressions of primal expectation, and of creation. Writing in the avant-garde magazine View, in a special issue of May 1942 that was devoted exclusively to Tanguy, the poet Nicolas Calas (1907–1988) wrote that ‘Tanguy’s objects await music, instead of evoking sounds as do instruments of forgotten civilisations’.11 The objects in Azure Day emit thin lines, incised into the paint surface to reveal the canvas beneath. They anchor the yellow pillar-like shape to the ground, small protuberances on the end of them taking seed in the previously barren ground, implying that initial moment of creation when Tanguy’s ‘Beings’ were too delicate and recent to support themselves. A network of similar lines connects together the figures to the left of the canvas. In terms that echo the language of Celtic myth, Gordon Onslow Ford described their function as carriers of energy: ‘Then came thin lines that suggested antennae, radiations, ley-lines, lines of force, lines of communication.’12

Azure Day was painted just two years before Tanguy left Europe for America, taking refuge from the impending war. The painting was subsequently transported to America by Tanguy’s dealer Pierre Matisse. It has been suggested that the dark tones and long shadows that dominate the picture, belying the clear blue sky implied by title, may hint at this threatening political situation in Europe. Indeed, when Tanguy arrived in America in 1939, his pictures underwent a dramatic change, becoming larger, more colourful and spacious. He stated: ‘I have a feeling of greater space and light here – more “room”. But that was why I came.’13

Lucy Bradnock

September 2004

Supported by The AHRC Research Centre for the Study of Surrealism and its Legacies.

Notes:

Explore

- abstraction(8,615)

-

- from recognisable sources(3,634)

- emotions and human qualities(5,345)

-

- subconscious(62)

- space(177)

- diseases and conditions(1,487)

-

- dreaming(213)

- countries and continents(17,390)

-

- France, Brittany(170)

You might like

-

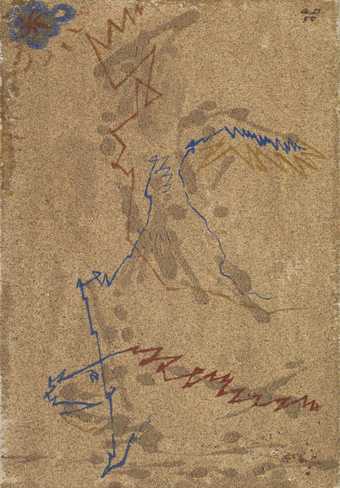

André Masson Ibdes in Aragon

1935 -

Man Ray Pisces

1938 -

Max Ernst Men Shall Know Nothing of This

1923 -

Max Ernst Forest and Dove

1927 -

Yves Tanguy The Invisibles

1951 -

Hans Bellmer Peg-Top

c.1937–52 -

Max Ernst Celebes

1921 -

Gordon Onslow-Ford A Present for the Past

1942 -

Max Ernst Pietà or Revolution by Night

1923 -

Francis Picabia Portrait of a Doctor

c.1935–8 -

André Masson Star, Winged Being, Fish

1955 -

Boris Taslitzky Study for ‘The Death of Danielle Casanova’

1949 -

Francis Picabia Otaïti

1930 -

Natalia Goncharova Country by Day

c.1911 -

Yves Tanguy A Thousand Times

1933