Not on display

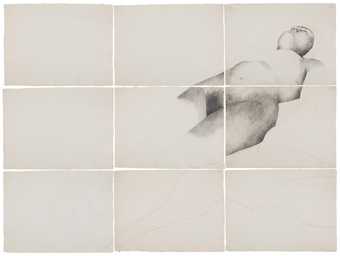

- Artist

- Raqib Shaw born 1974

- Medium

- Enamel, glitter, plastic beads and graphite on paper

- Dimensions

- Unconfirmed: 580 mm

- Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Presented by the Mottahedan Family 2007

- Reference

- T12373

Summary

Jane is a grotesque portrait on paper by the Indian-born British artist Raqib Shaw, the intricate details of which are crafted from plastic beads, enamel, glitter and graphite. The work’s composition echoes that of an oil painting of 1536–7 that depicts Jane Seymour, the third wife of the English King Henry VIII, that was made by the German artist Hans Holbein the Younger (held in the collection of the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna). Shaw’s portrait faithfully mirrors the three-quarter view, posture and most aspects of the regal attire depicted by Holbein in his painting, but departs dramatically in the representation of the subject’s face and head, which have been transformed into those of an open-jawed and tongue-wagging fish that resembles a piranha. Similarly, although the dress and ornamentation in Shaw’s reinvention are nearly identical to those in the sixteenth-century portrait, including the subject’s crimson velvet gown, square-cut neckline and bodice and gold-embroidered sleeves, there are conspicuous differences: the solid black headdress depicted by Holbein has been reimagined by Shaw in a rich pattern of gold-trimmed chequers filled with blue circles against a dark background. The tongue that stretches from the open, sharp-toothed mouth of Shaw’s sitter tapers into an upwards-floating ribbon that nearly connects with a pair of pointy bluish-grey tendrils that have sprung from a gaping hole in the subject’s chest. Together, the tongue and tendrils point towards a large blood-like splatter to the left of the fish head, out of which the charcoal outline of an arm and open hand have been drawn. Three further splotches of red hang in the air above the main subject’s head, and closer inspection of two of these shapes reveals the presence of a face in each, with their eyes and mouth wide open and their tongues protruding as if screaming.

Jane was created in 2006 in the artist’s London studio for Shaw’s solo exhibition Art Now: Raqib Shaw, which was held at Tate Britain in London that same year. It was conceived as part of a series of portraits based on paintings by Holbein that were on display concurrently at Tate Britain in the exhibition Holbein in England. Characteristic of Shaw’s technique, Jane is the product of extensive experimentation with unusual painterly materials, including glass, glitter, enamel and the manipulated constituencies of household paints that the artist first began exploring as a student as an inexpensive alternative to oil paint. The violence of metamorphosing Jane Seymour into a flesh-eating animal around whom clots of blood burst and scream has been interpreted as an attempt by Shaw to peel away the pretence of royal decorum, as symbolised by the Queen’s official court portrait, in order to expose the ruthlessness of Henry VIII’s regime. According to the art writer Hans Werner Holzwarth:

In Jane (2006) his abject embellishments all but hide Jane Seymour’s iconic image behind a fish-like mask, defiling the painting’s placid composure and invoking the violent turmoil of the age.

(Holzwarth 2008, p.428.)

For other commentators, Shaw’s portrait is itself an act of cultural defiance or defacement. The art critic Nick Hackworth has said of Shaw’s reinventions: ‘Simpler and bolder in their composition, they take Holbein’s famous portraits of Henry VIII, Jane Seymour and Anne Boleyn and cannibalise them … It is as if, in Shaw’s world, creation is unstable, species mutate at will and animals explode mid-stride as if they were unstable chemical compounds.’ (Nick Hackworth, ‘Violence and Beauty Collide’, Evening Standard, 1 December 2006, http://www.standard.co.uk/arts/violence-and-beauty-collide-7390990.html, accessed 7 May 2015.) Furthermore, when discussing the inception and meaning of his Holbein works in 2007, Shaw suggested that his role as an artist is to rejuvenate the icons and symbols of the past:

Portraits, like everything else, are mere pegs to hang other issues on. I am also aware that Henry and Holbein have been dead for centuries and so will we pass away, but the symbols remain.

(Quoted in Carey-Thomas 2007, p.90.)

Further reading

Lizzie Carey-Thomas (ed.), Keep on Onnin’: Contemporary Art at Tate Britain, London 2007, p.90.

Hans Werner Holzwarth, Art Now Vol.3, London 2008, p.428, reproduced p.431.

Kelly Grovier

May 2015

Supported by Christie’s.

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Display caption

Shaw has copied Hans Holbein the Younger’s portrait of Jane Seymour, the third wife of Henry VIII, and playfully embellished it with dramatic explosions and animal features. What may appear as a desecration is regarded by Shaw as a homage that emphasises how this historical figure has been supplanted by her iconic portrait. ‘Henry and Holbein have been dead for centuries and so will we pass away, but the symbols remain’, he has said.

Gallery label, September 2008

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Explore

- emotions, concepts and ideas(16,416)

-

- emotions and human qualities(5,345)

-

- horror(180)

- formal qualities(12,454)

-

- defacement(257)

- clothing and personal items(5,879)

- wounded(135)

- individuals: female(1,698)

- royalty and social rank(345)

-

- queen(245)

You might like

-

Helen Chadwick The Labours I

1986 -

Helen Chadwick The Labours VIII

1986 -

Sir Anish Kapoor CBE RA Untitled

1989 -

Sir Anish Kapoor CBE RA Untitled

1989 -

Chris Ofili Untitled

1998 -

Jim Lambie Ska’s Not Dead

2001 -

Peter Kennard Maggie Regina

1983 -

C. K. Rajan Mild Terrors II

1991–6 -

C. K. Rajan Mild Terrors II

1991–6 -

C. K. Rajan Mild Terrors II

1991–6 -

Sutapa Biswas To Touch Stone

1989–90 -

Tassaduq Sohail Untitled (Coloured People)

1992 -

Raqib Shaw Self Portrait in the Studio at Peckham (After Steenwyck the Younger) II

2014–15 -

Pio Abad, Frances Wadsworth Jones The Collection of Jane Ryan & William Saunders

2019 -

Nikhil Chopra Drawing a Line Through Landscape

2017