Not on display

- Artist

- Mark Rothko 1903–1970

- Medium

- Oil paint, acrylic paint, glue tempera and pigment on canvas

- Dimensions

- Support: 2667 × 3812 mm

- Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Presented by the artist through the American Federation of Arts 1968

- Reference

- T01031

Summary

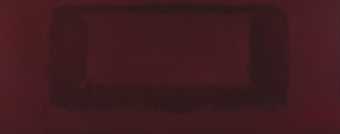

Black on Maroon is a large unframed oil painting on a horizontally orientated rectangular canvas. The base colour of the painting is a deep maroon. As is suggested by the work’s title, this is overlaid with a large black rectangle, which in turn encloses two slimmer, vertical maroon rectangles, suggesting a window-like structure. The black paint forms a solid block of colour but the edges are feathered, blurring into the areas of maroon. Different pigments have been used within the maroon, blending the colour from a deep wine to a muted mauve with accents of red. This changing tone gives a sense of depth in an otherwise abstract composition.

Black on Maroon was painted by the abstract expressionist artist Mark Rothko. He is best known, alongside fellow Americans Barnett Newman and Robert Motherwell, as a pioneer of colour field painting. The movement was characterised by simplified compositions of unbroken colour, which produced a flat picture plane. Black on Maroon was painted on a single sheet of tightly stretched cotton duck canvas. The canvas was primed with a base coat of maroon paint made from powder pigments mixed into rabbit skin glue. The glue within the paint shrank as it dried, giving the painting’s surface its matt finish. Onto the base Rothko added a second coat that he subsequently scraped away to leave a thin coating of colour. The black paint was then added in fast, broken brushstrokes, using a large commercial decorator’s brush. With broad sweeping gestures Rothko spread the paint onto the canvas surface, muddying the edges between the blocks of colour, creating a sense of movement and depth. Accents of red acrylic paint were dabbed onto the lower left corner. With time these have become more apparent as the pigments within the maroon portion of the canvas have faded at different rates.

In early 1958 Rothko was commissioned to paint a series of murals for the exclusive Four Seasons restaurant in the Seagram Building in New York, designed by Mies van der Rohe and Philip Johnson. Rothko was interested in the possibility of having a lasting setting for his paintings to be seen as a group. He wanted to create an encompassing environment of the sort he had encountered when visiting Michelangelo’s vestibule in the Laurentian Library in Florence in 1950 and again in 1959:

I was much influenced subconsciously by Michelangelo’s walls in the staircase room of the Medicean Library in Florence. He achieved just the kind of feeling I’m after – he makes the viewers feel that they are trapped in a room where all the doors and windows are bricked up, so that all they can do is butt their heads forever against the wall.

(Quoted in Breslin 2012, p.400.)

Rothko started work on the Seagram commission in a large new studio, which allowed him to simulate the restaurant’s private dining room. Between 1958 and 1959 Rothko created three series of paintings, but was unsatisfied with the first and sold these paintings as individual panels. In the second and third series Rothko experimented with varying permutations of the floating window frame and moved towards a more sombre colour palette, to counter the perception that his work was decorative. Black on Maroon belongs to the second series. By the time Rothko had completed these works he had developed doubts about the appropriateness of the restaurant setting, which led to his withdrawal from the commission. However, this group of works is still referred to as the ‘Seagram Murals’.

The works were shown at Rothko’s 1961 retrospective at the Whitechapel Art Gallery in London, and in 1965 Norman Reid, then Director of Tate, approached Rothko about extending his representation in the gallery’s collection. Rothko suggested a group of paintings from the ‘Seagram Murals’, to be displayed in a dedicated room. Black on Maroon was the first painting to be donated in 1968, although it was known as Sketch for ‘Mural No. 6’ or Two Openings in Black Over Wine. The following year Reid provided Rothko with a small cardboard maquette of the designated gallery space to finalise his selection and propose a hang. (This maquette is now in Tate’s Archive, TGA 872, and is reproduced in Borchardt-Hume 2008, pp.143–5.) Rothko then donated eight further paintings and the title of Black on Maroon was brought in line with the rest of the group (Tate T01163–T01170), four of which are also titled Black on Maroon and four Red on Maroon (Tate T01163–T01170). The ‘Seagram Murals’ have since been displayed almost continuously at Tate, albeit in different arrangements, in what is commonly termed the ‘Rothko Room’ (for installation views see Borchardt-Hume 2008, pp.98, 142).

Further reading

Simon Wilson, Tate Gallery: An Illustrated Companion, London 1991.

Achim Borchardt-Hume (ed.), Rothko: The Late Series, exhibition catalogue, Tate Modern, London 2008, reproduced pp.114–15.

James Breslin, Mark Rothko: A Biography, Chicago 2012.

Phoebe Roberts

May 2016

Supported by the Terra Foundation for American Art.

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Display caption

This is one of a series of large paintings Rothko made for a fashionable New York restaurant. By layering the paint, he created subtle relationships between the muted colours. They are much darker in mood than his previous works. He was influenced by the atmosphere of a library designed by the Italian artist Michelangelo (1475–1564). Rothko recalled the feeling of being ‘trapped in a room where all the doors and windows are bricked up’. A restaurant, he decided, was the wrong setting for these paintings. Instead, he presented the series to Tate gallery.

Gallery label, June 2020

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Technique and condition

Black on Maroon is painted on a single sheet of US cotton duck stretched tightly over a strainer. Constant tension over the large surface is maintained by a simple but effective internally sprung system of cross bars bowed and jammed between the outer bars. The only fixing that prevents the bars from springing out of position is a single screw driven through the sides of the outer frame.

The canvas was prepared for painting with a base coat of maroon paint made from powder pigments stirred into rabbit skin glue. Mark Rothko then enriched the colour with a coat of maroon oil paint applied with a brush and scraped away to leave a thin skin of colour. The surface dried to a soft sheen. Further depth of maroon was painted to the far left and far right in a subtly-different pigment mixture.

Using a large decorator’s brush, Rothko applied the black paint vigorously in broken strokes followed by broad sweeping gestures, scuffing the paint, spreading it and feathering the edges. Any splashes that fell across the red ground were left. This glue based paint, initially fat and bulky, shrank on drying to from a brittle, mainly matt, layer.

Accents of thick red acrylic paint were stippled on to the lower left corner to catch the light. These are now more apparent as the various red pigments used throughout the painting, have faded differentially, the greatest change being in the inorganic powder red in the base coat. Fading, which is inevitable, has been slow due to the low light levels preferred by the artist. In the forty years since the mural was painted, this unstoppable process has transformed maroon paint from a rich wine shade to a subtle violet, veiled appearance. Patches of intense red indicate where the most stable red pigments were used, principally to the far left and right and in a soft maroon haze at the top right.

The painting is not varnished. Despite the colour change, the painting is in good condition. A few finger prints and scratches from intimate contact in the past have caused permanent alterations to the paint surface. Surface dirt was removed in 2000.

Mary Bustin

July 2000

Catalogue entry

Not inscribed

Oil on canvas, 105 x 144 (266.5 x 366)

Presented by the artist through the American Federation of Arts 1968

Exh:

Mark Rothko, Museum of Modern Art, New York, January-March 1961 (works not numbered, repr. in colour) as 'Sketch for Mural No.6 1958'; Whitechapel Art Gallery, London, October-November 1961 (36, repr. in colour); Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, November-December 1961 (37); Palais des Beaux-Arts, Brussels, January 1962 (37); Kunsthalle, Basle, March-April 1962 (38, repr. in colour); Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Moderna, Rome, April-May 1962 (38, repr.); Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, December 1962-January 1963 (33)

Lit:

John Fischer, 'The Easy Chair' in Harper's Magazine, CCXL, July 1970, pp.16-23; Sir Norman Reid, 'The Mark Rothko Gift: A Personal Account' in The Tate Gallery 1968-70

(London 1970), pp.26-9, repr. in colour p.27

Repr:

Art News, LXIX, January 1961, p.38 in colour; The Tate Gallery

(London 1969), p.183 in colour

The nine pictures T01031 and T01163-70 were among those originally painted to decorate the Four Seasons Restaurant in the Seagram Building, New York (the skyscraper in Park Avenue designed by Mies van der Rohe and Philip Johnson). Writing soon afterwards in the catalogue of Rothko's touring exhibition, Peter Selz recorded: 'For about eight months [in 1958-9], Rothko was completely occupied in the execution of his mural commission. When it was finished, and the artist had actually created three different series, it was clear to him that these paintings and the setting did not suit each other.' Rothko therefore decided to withhold his pictures, which remained in his possession, and returned the amount already paid to him.

The mural project was initiated jointly by Philip Johnson and Mrs Phyllis Lambert, acting for her father Samuel Bronfman, the owner of the Seagram Company. There was apparently no formal commission. Rothko was simply invited to do what he wanted in that particular room and was given the dimensions of the space (27 x 46ft) to work from. He erected scaffolding of the exact dimensions of the dining-room in his studio in the Bowery, where the pictures were painted.

Mrs Rothko told the compiler in 1970 that, as far as she could remember, her husband did not know what the room would be used for when he undertook the commission and certainly was unaware that it would be turned into a restaurant. However Philip Johnson states (letter of 30 March 1972): 'The space was always intended to be a restaurant and Mr Rothko was thoroughly aware of this. The number of the pictures for the room was never specified. He was given carte blanche

to design the wall decoration any way he chose. There were no other conditions.'

In an earlier letter of 25 February 1970, Philip Johnson recalled that the pictures 'were intended to be hung high up on the wall in order that the heads of the diners would be below the paintings. The bright orange vertical was to be on the end wall as a sort of theme piece.' The retrospective exhibition of 1961-2 included a picture called 'Mural for End Wall' 1959, measuring 266.7 x 287cm.

Further light is thrown on the project by the reminiscences of John Fischer recorded in Harper's Magazine. Mr Fischer met Rothko by chance on a transatlantic liner in June 1959 at a time when the artist was still working on these murals, and Rothko talked freely to him about them; Mr Fischer afterwards made notes of their conversations.

'Rothko first remarked that he had been commissioned to paint a series of large canvases for the walls of the most exclusive room in a very expensive restaurant in the Seagram building - "a place where the richest bastards in New York will come to feed and show off".

'"I'll never take on such a job again," he said. "In fact, I've come to believe that no painting should ever be displayed in a public place. I accepted this assignment as a challenge, with strictly malicious intentions. I hope to paint something that will ruin the appetite of every son of a bitch who ever eats in that room. If the restaurant would refuse to put up my murals, that would be the ultimate compliment. But they won't. People can stand anything these days."

'To get the oppressive effect he wanted, he was using "a dark palette, more somber than anything I've tried before".

'"After I had been at work for some time," he said, "I realized that I was much influenced subconsciously by Michaelangelo's walls in the staircase room of the Medicean Library in Florence. He achieved just the kind of feeling I'm after - he makes the viewers feel that they are trapped in a room where all the doors and windows are bricked up, so that all they can do is butt their heads forever against the wall.

'"So far I've painted three sets of panels for this Seagram job. The first one didn't turn out right, so I sold the panels separately as individual paintings. The second time I got the basic idea, but began to modify it as I went along - because, I guess, I was afraid of being too stark. When I realized my mistake, I started again, and this time I'm holding tight to the original conception"' (copyright 1970 by Harper's Magazine).

Commenting on this, Bernard Reis added (21 February 1974):

'Rothko did not give up the Four Seasons commission because he felt his paintings would not shock "every son of a bitch who ever eats in that room". He gave up the commission because he felt that a fashionable dining room would be the wrong place to display paintings such as his. He was always interested in having his paintings establish a certain contemplative mood for the viewer.

'On one occasion, we had a conference with Mr Stone, the architect for the Kennedy Memorial Center. Mr Stone started the conference by pointing out that there would be two dining rooms - one for the caviar high-class trade, and one for the general public. He wanted Rothko to do something for the fashionable restaurant. Rothko conveyed to Mr Stone that his pictures were not suitable as a decoration for a restaurant or any other place where people gathered only to eat and drink.

'The Harvard murals were entirely different. They were placed in a room which was intended to be the meeting room of the Board of Trustees.

'Rothko stated to Stone that he would be willing to create murals for a room in which memorabilia of Kennedy would be displayed. This offer was not accepted.

'I know that Rothko admired the dark murals in the Medici library. He felt that these created just the kind of feeling he was after. That was because he wanted viewers to be affected by his pictures. As you know, Rothko never wanted his pictures to be brightly lighted. In addition, he never wanted them to be shown with other pictures. He always wanted a room. He was, therefore, happy when Mr and Mrs De Menil approached him for the murals for the Houston chapel ...

'Even though he had not made up his mind about the restaurant job, before he left for Europe he told me that he thought it would be foolish to be tempted by a large commission rather than continue along the lines he was following in creating rooms of a proper contemplative mood.'

Neither Bernard Reis nor James Brooks, who occupied a studio the floor above Rothko's at the time the Four Seasons murals were being painted, recalls Rothko saying anything about his 'malicious intentions' and Mr Reis suggests that this is the kind of remark he was more likely to make to a stranger than to an intimate friend. However Richard Arnell told the compiler that he had also heard Rothko say that he wanted 'to put the diners off their meals'.

All the Four Seasons pictures given to the Tate appear to come from the second or third series. Three of them (T01031, T01166

and T01170) are dated 1958, T01165

was originally dated 1958 and later changed to 1959, and all the others are dated 1959. Of the six Tate pictures included in Rothko's 1961-2 retrospective exhibition, T01031 was entitled 'Sketch for Mural No. 6' and the others were described as follows:

T01168

'Mural, Section 2'

T01163

'Mural, Section 3'

T01165

'Mural, Section 4'

T01169

'Mural, Section 5'

T01167

'Mural, Section 7'

(The numbers probably refer to the order in which they were to be hung on the walls). The exhibition also included Nos.1, 4 and 7 of the series 'Sketch for Mural' (No.7 being dated 1958-9), none of which is now at the Tate. It would seem probable that T01166

and T01170, both of which are dated 1958, are from the same series 'Sketch for Mural' as T01031, and this may also apply to T01164, which resembles them in style, though it is dated 1959. The only picture from the first series that has been definitely identified is 'White and Black on Wine' 1958, formerly in the collection of William S. Rubin, New York, and now in that of Ben Heller, which has two horizontal soft-edged rectangular patches of white and black on a wine-coloured ground. It would appear therefore that Rothko began by painting in a style similar to that of his ordinary pictures of the period and later evolved a more bare and monumental treatment specially adapted to the needs of a large-scale mural composition. The pictures of the second series 'Sketch for Mural', which show considerable variations, are clearly transitional works. They were followed by what James Brooks (letter of 22 April 1976) has aptly described as 'the abandonment of his characteristic soft, fading edge in favor of a hard edge - suggesting the after-image of a window'. This is one of the features that relates this last series to the blank windows (not paintings) of the staircase room of Michaelangelo's Biblioteca Laurenziana in Florence, which produce a powerfully disturbing effect of enclosure on the spectator.

Rothko first mentioned the possibility of making a gift to the Tate in 1965 and discussed it with the Director Sir Norman Reid many times in the course of the next four years before making up his mind. While he had a deep affection for England, he was concerned that the work would not be appreciated in London. The decisive factor which influenced him in the end was the thought that the pictures would be in the same building as Turner. His intention was that the works should form a homogeneous group and be seen alone in a space of their own. The final selection was made towards the end of 1969 in his studio in New York, when he and Sir Norman chose a further eight paintings to accompany the one he had presented earlier in 1968. He planned the arrangement himself with the aid of a mock-up of the space they were to occupy and even cut a sample of the wall colour from the studio. However by a sad irony the pictures arrived in London on the very day of his death, and he was never able to see them in position.

The titles used for T01163-70 are in accordance with a list provided by the artist in a letter of 7 November 1969, each picture being identifiable by a number marked on the back. The present work has been known as 'Sketch for Mural No. 6' and as 'Two Openings in Black over Wine', but its title has now been brought into line with those of the other works from the series.

Published in:

Ronald Alley, Catalogue of the Tate Gallery's Collection of Modern Art other than Works by British Artists, Tate Gallery and Sotheby Parke-Bernet, London 1981, pp.657-61, reproduced p.657

Features

Explore

- abstraction(8,615)

-

- non-representational(6,161)

-

- colour(2,481)

- emotions and human qualities(5,345)

-

- contemplation(141)

- pessimism(45)

You might like

-

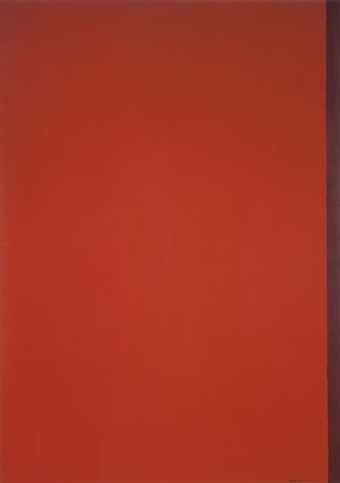

Mark Rothko Light Red Over Black

1957 -

Mark Rothko Black on Maroon

1959 -

Mark Rothko Black on Maroon

1959 -

Mark Rothko Red on Maroon

1959 -

Mark Rothko Black on Maroon

1958 -

Mark Rothko Red on Maroon

1959 -

Mark Rothko Red on Maroon

1959 -

Mark Rothko Red on Maroon

1959 -

Mark Rothko Black on Maroon

1958 -

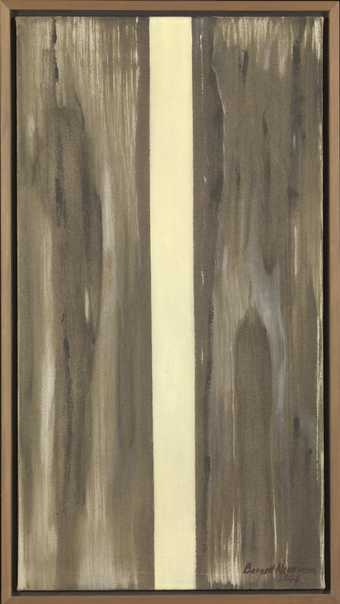

Barnett Newman Eve

1950 -

Hans Hofmann Pompeii

1959 -

Mark Rothko Untitled

c.1946–7 -

Mark Rothko Untitled

c.1950–2 -

Hans Hofmann Nulli Secundus

1964 -

Barnett Newman Moment

1946