Introduction

Tate’s research project Reshaping the Collectible: When Artworks Live in the Museum aims to develop new collection management and conservation models to inform how particularly complex and challenging works of art might live and flourish within the museum. For the purposes of this project, ‘challenging’ artworks have been defined as those works that in their very nature appear ‘unruly’1 – works that exist in different forms and within different contexts; works that defy conventional distinctions between the archive, the record and the artwork; works that change or develop over time and depend not only on moments of re-engagement with the artist but also on external socials worlds and networks of people, technologies, materials and skills.

As an active collecting institution, Tate acquires a considerable amount of material for the various parts of its collection on an annual basis. The development of Tate’s collection, whether through the acquisition of artworks for Tate’s collection of British and international art or archival material for Tate Archive, is a core activity that directly relates to the institution’s purpose and contributes to fulfilling its mission to increase the public’s knowledge, understanding and enjoyment of British art from the sixteenth century to the present day and of international modern and contemporary art.2

As an institutional priority, much of Tate’s infrastructure is designed towards supporting/facilitating the acquisition of new artworks and archival material. Consequently, significant institutional resource and focus is committed to realising this objective. Firstly, the pursuance of acquisitions forms a major part of the roles within multiple departments and sub-teams including: the curatorial departments across the collections of British art, international art and the archive; the acquisition co-ordination team; the various acquisition conservators based within the different conservation media sub-teams; the collection management teams, including the acquisition and long loan registrar team (in which I sit as an embedded researcher),the art handling team; and the photography team. Secondly, key institutional collection-focused groups/committees are tasked with the consideration of acquisition and long loan candidates as possible additions to the collections. These include the Monitoring Group, International Monitoring Group, Collection Group and Collection Committee; acquisition and long loan candidates finally require consideration and sign-off from Tate’s Board of Trustees.

The principal formal document that encapsulates Tate’s collecting ethos and acts as a guide for Tate’s approach to acquisitions is its Acquisition and Disposal Policy. This document straightforwardly details Tate’s collecting remit and highlights, by individual artwork media-type, the criteria that govern acquisition. The policy is not only designed to reflect the existing collection but is intended to be forward-thinking and broadly indicate the manner in which the collection is anticipated to expand and develop in the future. As a working institutional document, this policy is internally reviewed every three years and requires formal approval by the Board of Trustees, while more urgent amendments can be submitted for approval more regularly. The ongoing review of this evolving policy can be recognised as a means of facilitating institutional change, allowing Tate’s collecting remit to best reflect the evolving understanding and development of Tate’s mission.

As an embedded researcher for the project in collection management, my report will explore Tate’s existing working practices for registrars dealing with acquisitions and examine the instances where these practices are tested by the nature and complexity of challenging artworks. The discussion will be rooted in practice – through the use of individual artwork case studies, specific challenges to current working procedures will be highlighted, indicating instances of institutional change and the possible implications for the wider museum and art world.

Blurred boundaries

In 2016, a significant amendment to Tate’s Acquisition and Disposal Policy was introduced to facilitate the development of the Material and Studio Practice collection, effectively demonstrating the institution’s ability to adapt to meet emerging collecting challenges. The stimulus for the development of this collecting area was the gift to Tate of Barbara Hepworth’s Palais de Danse studio and the contents of her Trewyn studio (the site which became the Barbara Hepworth Museum in 1976) by the trustees of the Dame Barbara Hepworth Will Trust. During Tate’s consideration of the proposed gifts, it was determined that the types of material offered – including tools, equipment, furniture and fittings – fell outside of the existing collecting remits either for Tate’s collections of British and international art, or for Tate Archive; this would therefore make the material offered ineligible for formal acquisition by Tate. However, due to the material’s importance in illustrating Hepworth’s artistic practice, along with the strong institutional support for the acquisition, it was agreed that Tate should internally formulate a new collecting area that would facilitate the material’s acquisition.

The proposal was considered in accordance with the stated procedure for the review and amendment of the Acquisition and Disposal Policy, and the Board of Trustees formally reviewed and authorised the Material and Studio Practice collection in November 2016. Although the creation of this new collecting area was instigated by the acquisition of the Hepworth studio contents, the Material and Studio Practice collection is not limited to this material – in the future, material of a similar nature will also be eligible for formal acquisition under the same collecting criteria, which may perhaps already apply to materials relating to J.M.W. Turner currently considered part of Tate Archive.

The following noteworthy provision in the ‘Criteria Governing Acquisitions’ section of the Acquisitions and Disposal Policy relating to the Material and Studio Practice Collection contains an unambiguous reference to the potential future disposability of items within this part of the collection:

It is understood that on acquisition, if future research reveals that any individual item is no longer considered relevant to the context of a site or to the period of an artist’s working practice, or an object becomes unsuitable for retention, disposals may be made in line with Tate’s disposal policy.3

The overt inclusion of this caveat demonstrates the conditional anticipation that disposal may be expected in the future, and therefore should be an element of consideration during the acquisitions process. This is noteworthy in its uniqueness, as Tate’s other collections do not include any equivalent reference to disposal. This, therefore, signals a distinction in the status of these different materials, whereas the disposal/deaccessioning of items within the other collections is regarded as uncommonly exceptional and a decision that requires significant institutional consideration and Trustee approval.

Despite every effort a contemporary art museum may make to clearly articulate and distinguish between the different parts of its collection, there will always exist artworks or artist-related material that fails to find a comfortable place within the museum’s structure, whether as part of the collection, artwork/artist documentation, the archive or gallery records. Materials often blur the boundaries between these distinctions and compel the institution to question its internal structures, the nature of its collections and the manner in which the museum collected in the past, collects currently and will collect in the future. Since the opening of Tate Gallery in 1897 the institution has steadily developed and grown its collections, with the artwork collection alone now containing over 76,000 works. Beginning in the final quarter of the twentieth-century and rapidly continuing into the twenty-first century, in correlation with artistic engagement with ever more sophisticated technologies and diverse working practices, Tate has exhibited a strong commitment to the acquisition of technically complex artworks, as well as artworks comprised of non-traditional media. These types of artworks, with their variable and developing states, are more predisposed to question the boundaries of the Tate’s various collections. Although Tate has displayed pragmatic flexibility in the development of new collection types and collecting areas, as illustrated through the development of the Material and Studio Practice collection, it must continue to review its working practices; not only to best reflect and collect the art of contemporary society, but also to best position itself to accurately classify, collect and manage the objects/artworks that sit on these boundaries.

Fig.1

Richard Wilson

She came in through the bathroom window 1989

Tate T14354

© Richard Wilson

Any uncertainty in the accurate classification of material can have a direct impact on its documentation and management. It may ultimately have a considerable impact on Tate’s ability to best safeguard, display and interpret this material on behalf of the nation. A relatively simple area of tension can be found in the decision-making process that determines whether materials should enter the artwork collection or the archive. An example that explores this process can be found in a series of Richard Wilson works, each titled She came in through the bathroom window, and all dated 1989 (Tate T14354–T14358). One of them (fig.1) is a major installation that when displayed requires the removal of a section of the gallery window from its housing, which is then brought into the gallery space. The displaced window is held within the gallery space by a sealed metal armature that re-connects the displaced window with the gallery’s exterior wall/remaining windows. Accompanying the installation, as part of the same overall acquisition, were four documentary objects (two drawings and two sculptural models, Tate T14355–T14358) that relate to the installation. During the acquisition process, the acquisition’s proposer acknowledged that these materials would usually sit within the archive collection. In the end, however, they were accessioned into the art collection.

This example raises the question of whether Tate has a sufficiently strong and clearly defined process for determining the ‘collection-type’ of these kinds of materials, or if this is decided on an object-by-object basis. In relation to the Richard Wilson ‘documentary’ objects, when acknowledging the fixed nature of the works themselves, might a different decision have been made for the acquisition under different circumstances? Several factors may possibly have played a role in this decision: the ‘documentary’ objects accompanied the acquisition of the installation which they documented; there are similar Richard Wilson ‘archival-type’ works already in the art collection (Watertable T12489; Over Easy T12492; and Butterfly T12495); and the acquisition was proposed by a curator of British art with special responsibility for the archive – might a different decision have been made if proposed by another type of curator? The determination of an object’s status and collection-type has crucial implications on how it is managed and cared for, as well as the impact on the financial value of the material. The value of art collection works is, generally speaking, significantly higher than items from within an archive collection. Institutions must ensure that a diligent and evidence-based approach is undertaken when designating collection-type. The exploration of these factors does not mean to suggest that these works were catalogued incorrectly, it merely tries to demonstrate the ambiguity that certain types of material can present, the possible role of interpretation in determining status and the impact this decision can have on collection care/management.

Artworks that generate archival material

Fig.2

Tania Brughera

Tatlin’s Whisper #5 2008

Tate T12989

© Tania Brughera

Aside from the artworks which sit on the boundary between Tate’s art and archive collections, there are those works that generate archival or documentary material during their life in the museum. These instances highlight areas of tensions within Tate’s collection care policies and working practices whereby the uncertain status and purpose of this generated material leads to confusion as to how it should be managed and cared for in the long term. This is an emerging concern at Tate and cuts across the conservation, archive and collection management teams. Within Tate’s collection, these occurrences most often relate to the documentation of performance-based artworks that exhibit changing or bespoke display parameters. A notable example that illustrates this point can be seen in Tania Bruguera’s Tatlin’s Whisper #5 2008 (fig.2), a performance work in which two uniformed police officers mounted on horses use a variety of crowd-control methods to move, guide and control visitors within a gallery or exhibition space. As part of the work’s acquisition agreement – made between the artist, the artist’s gallery and Tate – Tate (as the purchaser) accepted the responsibility for the creation and conservation of an ongoing archive for the work comprised of the material generated from each new performance.

As previously alluded to, such material (which will expand over time) has an ambiguous status within the institution and, as a result, presents documentation challenges – specifically, should this be managed as a component in the artwork collection or instead be integrated into Tate’s gallery records or archive collection? Presently, this material is managed as a component in the artwork collection, even though it perhaps has greater similarities and congruency with the archive collection. This circumstance has developed further complexities stemming from the below provision in the acquisition agreement:

The buyer [does] not have the right to show the resulting documentation of the piece (including interviews [with] the participants or the curators) as a substitution of the work nor as a [sic] companion material during the exhibition of the work. The documentation will never be shown instead of the work. The public view of the archive will be done solely for an exhibition surveying forms of documentation or archives in which case the piece has to be performed live and in addition will have, in a space next to it, the archival material on display.4

In spite of this clear stipulation from the artist, during the course of making loan arrangements with the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, San Francisco, it was established that the borrower would not be able to satisfy the specific conditions of the performance. However, due to the artist’s support of the exhibition, Tate received the artist’s express permission to solely lend documentary material on this occasion, and accordingly lent a film of the performance of the work at Tate Modern, London on the 26–27 January 2008, along with a redacted version of the acquisition agreement and the specifications for the performance. This adjustment in approach again questions the manner in which this documentary material should be handled and managed, creating further ambiguity over where it should be placed.

The difficulties of an institution determining the status of these somewhat ambiguous materials may be further compounded by the innate interpretability of the word ‘archive’. In the case of Tatlin’s Whisper #5, the artist’s specification that generated documentary material should be archived may perhaps be understood differently within an institution such as Tate, which has a clearly-defined and distinct understanding of the ‘archive’ and the boundaries between the archive and art collections. This disparity in understanding may possibly lead to a divergence between the artist’s intent for documentary material and the approach in which this material, in practical collection management terms, is documented, published and made publicly available.

The CMS as an internal dependency

Certain artworks, which will be explored as part of the Reshaping the Collectible project, can be recognised to maintain dependencies outside of the institution’s sphere of influence and control. These dependencies, both social and technological, can greatly influence the ongoing care, management, conservation and display of artworks within an institution’s collection. Within this report I would like to briefly discuss a distinct but related theme that draws attention to a possible type of internal institutional dependency. This dependency may have extensive and long-term effects on how all museums document and manage their collections.

Tate’s collection lies at the core of the institution and largely directs its range of public engagement programmes, while also motivating large-scale collection care and research activity. In contemporary museum practice, most museums, art galleries and institutions that own or manage collections employ an electronic collection management system (CMS) to aid in the logistical management and documentation of their collection. In Tate’s case, The Museum System (TMS) allows Tate to record collection activity efficiently and is an essential mechanism to accurately track and manage the necessary information Tate is obliged to maintain as a custodian of part of the UK’s national collection. Accordingly, TMS is utilised extensively to co-ordinate, track and document the majority of activity related to the collections of British and international art. The information captured ranges from the maintenance of core object information and conservation reporting to the co-ordination of displays/exhibitions and loans out.

While acknowledging the positive aspects of using a CMS, a reliance on this technology bears the risk that they may have a powerful shaping or limiting influence on an institution. This concept is perhaps highlighted by the apparent differences in documentation style and format for similar types of collection that are catalogued on differing collection management systems. How can Tate avoid the risk of its documentation practices being led by its core documentation tool? This risk may be heightened with the ongoing sophistication of CMS functionality and technology.

Within Tate, an area of tension in the use of CMS programmes is made visible through the distinct collections the institution holds. TMS is utilised as the art collection CMS, while different systems are employed to document and manage other parts of Tate’s collection – Calm, for Tate Archive; Symphony, for Tate’s Library collection. Tate employing distinct systems is not problematic in and of itself. Rather, it merely expresses the divergent requirements of the different collection-types and the capabilities that each system provides. However, when material from Tate Archive is included in displays or exhibitions at Tate sites, records designated as ‘supporting material’ are created on TMS to temporarily document the display of archival items. This is to help facilitate the exhibition planning and execution processes, aiding registrars to comprehensively document an entire Tate display, while providing a logistical record for co-ordinating transport, conservation and installation. However, the duplication of object records across two collection management systems may cause confusion and lead to the inaccurate documentation and tracking of these materials. This issue emanates from the isolated systems’ inability to communicate or exchange information between one another.

Artwork component management

TMS also plays a core role in documenting and co-ordinating the constituent components of artworks. These components are defined through their direct affiliation with an artwork and are categorised as either ‘part of an object’ or an ‘accessory’. A ‘part of an object’ component is any that can be identified as being an inherent part of the artwork; an ‘accessory’ is a component which is not considered part of the artwork – this commonly relates to an item used to pack, store or display the artwork. This distinction in status is fundamental and directly influences Tate’s duty of care in preserving and maintaining these components, as well as aiding to meet the statutory requirements of auditors.

The functionality of TMS allows extensive flexibility in the manner and depth that components can be documented. However, perhaps the most crucial element from the collection management perspective can be found in TMS’s capacity to maintain the accurate and unbroken location documentation of all individual components. Tate’s registrar teams are the only parties authorised to update artwork locations on TMS, a practice which corresponds directly with Tate’s policy that all collections and deliveries of artworks (including all their constituent components) to, from or between Tate sites are coordinated by a member of the registrar department. To further ensure the accuracy of component documentation, Tate’s registrar teams are again the sole parties responsible for creating and amending the associated fields on TMS (apart from time-based media artwork components, as discussed later). Tate registrars work to accepted structural working practices on the manner and style of how components should be numbered, formatted and categorised to mitigate against the risk of non-standardised, inconsistent documentation. This centralised process again ensures that, for auditing purposes, Tate has a clearly documented understanding of all artwork components – knowing what they are, where they are located and from when. This forms a key mechanism for the tracking of accurate and detailed display histories for each work in the collection, thus enabling Tate to fulfil its statutory obligations.

Fig.3

Roman Ondák

Good Feelings in Good Times 2003, performed at Tate Modern, 10 March 2007

Tate T11940

Photo © Tate

A prevailing characteristic of registrar-created components can be seen in their representation of a material element, even for components intentionally created for a short period of time. The principal exception to this practice is found with the creation of exhibition format components for artworks/artwork components that only possess physical materiality when exhibited. An example of this can be seen in Roman Ondák’s Good Feelings in Good Times 2003 (fig.3), a performance artwork composed of several hired participants/actors repeatedly forming an artificially-created queue within an exhibition space. The procedure for documenting this work when displayed, whether for a single day or several instances over a set period at the same venue, is through creating a temporary exhibition format component and populating this record with the relevant display details and dates. Following the close of the display, the temporary component is deactivated but would always remain accessible for viewing as a means of fully preserving the work’s documentation and display history.

An example of an artwork that consists of relatively ‘simple’ constituent components can be seen in Ciprian Muresan’s large polyester and resin sculpture Plague Column #2 2016 (Tate T14912). In this case, there is a single ‘part of an object’ component – the single sculptural element; and two ‘accessory’ components – the case in which the sculpture is stored and the work’s certificate of authenticity. This example demonstrates the relative simplicity of component management for much of Tate’s collection. Certain artworks, however, present much greater documentation challenges.

The creation and management of time-based media (TiBM) components deviates from Tate’s standard working practices. Members of the TiBM conservation team, rather than registrars, are the party responsible for the creation and documentation of these components, initially borne out of necessity due to a lack of linked systems. TiBM conservators have the technical knowledge and background to most ably describe, document and manage these components, but they are also the only team within the institution that actively and regularly create new ‘part of an object’ components/media for existing artworks within collection. The TiBM conservation team are responsible for ensuring the digital preservation of works through the creation of new media files, including back-up duplicates, that may exist in either physical or digital forms, and the migration of media to more contemporary/longer-lasting formats. The new components that the TiBM conservation team create are frequently produced from existing media components, which are then documented individually on TMS in accordance with institutionally agreed documentation standards. This indicates a further divergence whereby TiBM components do not necessarily relate to a physically tangible element, but instead may represent a single digital media file on a hard drive or other storage device.

The development of new media components for TiBM artworks varies and relates to both the number and type of individual media elements that constitute the artwork or an artwork’s TiBM element; however, it can be assumed that the number of components will continue to grow throughout the artwork’s life within the collection. Tate’s current practice directs that all media components that demonstrate a distinct moment in the history of an artwork, even those that may seemingly appear redundant (through the creation of more contemporary file types or following the end of an exhibition format’s use), are still retained and continue to be documented as active components on TMS. These circumstances can conceivably contribute to collection management difficulties which, considering the growing number of TiBM components, may grow in number and frequency as time progresses.

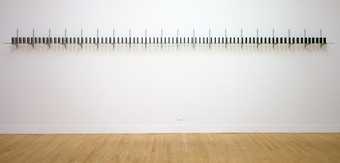

Fig.4

David Tremlett

The Spring Recordings 1972

Tate T01742

© David Tremlett

David Tremlett’s The Spring Recordings 1972 (fig.4) is an installation consisting of eighty-one recorded cassette tapes equally spaced on a glass shelf. The cassette tapes contain audio recordings, taken by the artist between May and June 1972, of the eighty-one counties of England, Scotland and Wales. When the work is exhibited, the recordings are successively played on a loop on a cassette player mounted on a nearby plinth and can be experienced by visitors through either headphones or speakers. As of August 2019, this work has 851 active components on TMS, primarily made up of varying numbers of media file-types, including ‘archival masters’, ‘artist supplied masters’, ‘artist verified proofs’, ‘duplicating copies’ and ‘exhibition copies’. It is imperative for Tate to retain certain file-types, such as the ‘artist supplied masters’, ‘artist verified proofs’ and ‘archival masters’, as well as to take into consideration the relationship between the number of media components with the eighty-one individual audio recordings that make up part of the artwork. The high number of components, however, does pose challenges to collection management practices. Firstly, the great quantity of components presents a greater risk that the activity of single components or small groups of components is misunderstood or incorrectly documented. This may perhaps be more of a risk for the registrar teams who, while not the party responsible for the component creation and documentation, regularly schedule and authorise activity relating to them. Secondly, artworks comprising high numbers of constituent components also stretch the functionality of TMS. For example, when these types of artworks are requested for loan, the standard process for producing loan agenda reports for consideration by the Loans Group cannot be followed. An alternative workaround must instead be used, and a non-standard process requires more time and resources, and risks errors.

The Spring Recordings raises key questions of collection management which I will explore during the Reshaping the Collectible project: what are the issues that artworks which evolve and change over time present to documentation practices? What information does the institution need to retain to appropriately document and chart the history of an artwork in the collection? Partly as a consequence of the departure from standard working practices, linked intrinsically with the extensive quantity of TiBM components and their capacity for growth, this has resulted in an area of least compliance for Tate’s documentation of the collection.

Determining the value of unconventional/complex artworks

Determining the financial value of artworks, even paintings, prints or sculptures, can be a difficult and inexact process. For artworks that are entirely or partly intangible, the dematerialised nature and varying/ambiguous statuses of the material that may make up the artwork further complicate its assigned value.

An excellent example that highlights challenges relating to the manner in which artworks that exhibit intangible or conceptual characteristics are valued can be found in Richard Bell’s Embassy 2013–ongoing. Richard Bell is an Aboriginal artist-activist who addresses themes of identity, place and politics through his artistic practice. Embassy is an installation which, when activated, acts as a public space for reflecting on and discussing experiences of oppression and displacement. Each new activation addresses themes of identity, place and politics in relation to the local context of its display. At the point of acquisition, the work is composed of: a large military-style tent; four placards (three proclaiming Aboriginal land rights and dispossession, and one used to designate the tent as the ‘Aboriginal Embassy’); archival material related to all past activations of the work; and screening rights to Alessandro Cavadini’s Ningla A-Na 1972, a documentary exploring Aboriginal activism in South-East Australia in the 1970s. The tent can be activated further with talks, performances, screenings and workshops by performers, activists, artists and thinkers. Archival material generated from each new activation is collected and forms part of the evolving artwork.

When considering the collection management challenges that this combination of tangible materials and intangible experiences illustrates, Embassy poses a fundamental question. What is the core nature of the artwork – the tangible materials that create the physical environment or the intangible experiences and political-activist activity that occurs within the space? No doubt arguments can be made to express support for either interpretation. However, there may not necessarily be a categorical answer. Ultimately, discussions regarding the status of the tangible materials, the necessity of their inclusion when displaying the work and their relationship to the intangible experiences, can have a practical impact on the means in which the work is cared for, lent and insured.

Tate’s current practices do not allow for a single artwork’s value to be broken down into distributed valuations for its component parts; a good example of the limitations of a collection management system dictating institutional practice. Similarly, in the case of artworks composed of both tangible and intangible materials, the insurance value in practical terms would solely sit with the tangible components (unless these are identified as replaceable). In the case of Embassy, if it is determined that the core component of the artwork is the intangible experiences, it would appear illogical and inaccurate for the tangible materials to represent the full artwork insurance value. This discussion is made more complex through the artist’s direction that the work can be displayed either inside or outside, including in non-climate-controlled spaces (to maintain the accessibility and spirit of earlier non-museum activations). This adds another collection management challenge, as the identification of the tangible materials (i.e. the tent, placards and archival material) as permanent components required for every activation would also, as standard practice, make them inappropriate for outside display due to preservation concerns in order to maintain the long-term care of the work.

The art sector has slowly adapted to the development of immaterial artworks, such as performance, which are transacted more akin to content and intellectual property rights rather than more ‘traditional’ tangible objects.5 This point draws attention to the relationship between public museums and the art market – nuanced but inextricably intertwined.6 For example, when purchasing works either directly from artists or from commercial galleries, public institutions frequently negotiate sale prices for the public benefit. However, the benefits of these arrangements are reciprocal as the inclusion of an artist’s work in museum collections or exhibitions may greatly raise the profile and prestige of the artist. Public institutions, which are often perceived as somewhat ‘objective’, act as legitimising agents reinforcing notions of artistic legitimacy, authenticity and value – applying to both cultural and commercial art circles.7 The visibility of a public institution’s acquisition of an artist’s work will also increase the value of the remainder of their work.8 Tate addresses this through rigorous governance and making transparent its acquisition processes and conflicts of interest.

Tate must carefully consider the impact it may have when acquiring material in a form not previously considered ‘collectible’ as it may have far-reaching effects on the wider art world/market and the nature of institutional and private collecting. In terms of the themes that the Reshaping the Collectible research project will explore, the wider impact of Tate’s legitimising potential is especially relevant to debates regarding how an artwork is constituted. This may commonly stem from the increasingly ambiguous and flexible boundaries that exist between the artwork, the archive and the gallery record. This raises a potential issue in that Tate may be seen to be commercialising material that otherwise may have been considered as uncollectible.

In addition to the challenges of not assigning individual values to components, artworks which exist in different forms can produce additional collection management challenges when lending the work. This can relate to both the insurance value during loan and, for certain works, their customs status when lending outside of the European Customs Union.

Fig.5

Suzanne Lacy

The Crystal Quilt 1985–7

Tate L03198

© Suzanne Lacy

Suzanne Lacy’s The Crystal Quilt 1985–7 (fig.5) is a large-scale installation composed of a quilt, photographs, film, video, audio recording, slide projection, poster and programme. The artwork’s material originated from Lacy’s extensive participatory performance of the same name in May 1987, which involved mass action, spoken word and sound performed by 430 women over the age of sixty. Although undoubtedly a single artwork, not all of the components are required when displaying the work; the quilt or film can be displayed individually and still represent the entire artwork. As of August 2019, this work is currently on long-term loan to Tate from the Tate Americas Foundation (TAF, formerly the American Fund for Tate Gallery) and is indemnified accordingly. As with all TAF long loans, this work will in time be gifted to Tate.

Challenges were recently posed when the artwork’s quilt component was lent individually to the exhibition Suzanne Lacy: We Are Here at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (April–August 2019). The first challenge concerned how the now two groups of component/s would both continue to be indemnified. As a long loan to Tate, the artwork is indemnified through the UK’s Government Indemnity Scheme (GIS) when in Tate’s care. Usual practice when lending a work on long loan to Tate is to cancel the GIS indemnity following the borrower’s collection of the work from a Tate site, at which point the borrower’s insurance cover comes into effect. However, as only part of the work was lent (whilst the remainder of the components were retained on-site), it was not possible to cancel the existing GIS indemnity as the remaining materials still required coverage. As Tate does not provide distributed valuations for the component parts of artworks it was not possible to amend the indemnified values on both policies, which in theory could then be combined to total the full artwork value. Current working practices instruct that if only part of an artwork is lent, and which if lost, would be impossible to replace (therefore making the work unexhibitable in the future), then this should be valued and insured at the full artwork value. However, should this exact approach be taken for artworks that exist in different forms? In the case of The Crystal Quilt, the artwork could continue to exist and be displayed even if the quilt component is lost or made unexhibitable.

This example also highlights a related challenge concerning the customs status of the work when lending only the quilt component. During the long loan acquisition process, this work was imported into the UK under Tate’s National Imports Relief Unit (NIRU) designation, meaning that the shipment (and Tate) were exempt from customs duty on import into the UK. However, when a work that is on an institution’s NIRU is exported (including temporary export for short-term loan), the material should be exported under the same NIRU conditions. At this point, the material is effectively taken off our NIRU account and on the return of loan would be re-imported back onto our NIRU. The Crystal Quilt highlights the logistical challenges that can stem from artworks which exist in different forms – how might Tate overcome these types of artwork challenges, which are likely to increase in the future?

Methodology/conclusion

Working within the Reshaping the Collectible project team, I have the opportunity to collaboratively consider the effectiveness of conventional working practices, especially those that are tested by the types of artworks and challenges highlighted within this report. As an embedded researcher within the registrarial team for acquisitions and long loans, I am able to apply this thinking to the team’s routine tasks, including the coordination of all logistical arrangements when acquiring new acquisitions (of all collection-types) for Tate’s collection, the management of long-term loans and the daily collection management/documentation tasks associated with managing the collection at Tate Store. Being an embedded researcher in this way allows me to gather first-hand experience of the many challenges the institution’s working practices face when encountering complex artworks or ambiguous material. The wide nature of the research project also offers me the opportunity to work with Tate’s other collection registrar teams (displays and loans out); these diverse perspectives allow me to have a broad overview of the distinct collection management/documentation challenges that each team encounters.

Promoting a robust, articulate and transparent system for determining the collection-type of material within the collection is vital, as this has an enormous impact on how items are documented, managed and cared for. This approach would apply to new acquisitions, as well as those artworks/items already within the collection which blur the boundaries between the artwork, archive and gallery record; the collection-type of an object should not be fixed but should instead reflect a contemporary understanding of artistic practice. Retaining this knowledge is not only crucial to documenting the history of a work, but also serves as a means of tracking the development of Tate’s collection and long-term institutional change. Further to this, the development of a method for the effective management of artworks that generate archival material is critical, as its current ambiguity presents certain risks to its ongoing documentation and care. This issue will be explored through the project’s case studies and with the aim of achieving procedures for the effective management of these types of material already present within the collection, as well as those that will emerge from future acquisitions.

Tate must ensure that it tailors it use of CMS functionality to most effectively document and manage its collections. However, moving beyond this, in order to resist the shaping effect of CMSs, Tate must ensure that it looks beyond the apparent capacity/limits of current functionality to identify documentation areas or processes that can be developed or improved. The complexity of the challenging works that the project will investigate may be of particular use to this research as their disruption of collection management and documentation practices may, in fact, aptly illustrate key areas which can be improved. With Tate’s upcoming TMS upgrade, I will explore the possibilities to most productively utilise expanded functionality to better document and manage Tate’s developing art collections.

Artworks composed of non-traditional media, perhaps existing in different forms or incorporating a dematerialised element, can commonly present challenges to our standard logistical working practices; for example, when assigning a value for insurance purposes or declaring a value when exporting/importing the work. Despite these challenges sometimes being unique to individual artworks, it is possible to recognise the need for Tate to formulate standard practices that facilitate an effective and accepted response to recurring challenges. Through liaising with internal collection management teams at Tate, as well as external partners, such as HM Revenue and Customs, Government Indemnity Scheme and fine art transport agents, Tate can develop flexible and robust working approaches that could be adopted across the institution, as well as shared across the wider sector. The importance of producing these guidelines should not be understated as these types of challenges can only be expected to grow when considering Tate’s diverse collecting activities and extensive lending programme.

Through interrogating Tate’s working practices and policies, with an appreciation of the processes of the wider museum sector, I intend to locate the points of friction that arise when confronted with the type of complex or challenging artworks/objects highlighted within this report. Working through these challenges as part of the research project team will better enable Tate to successfully collect, document, preserve and manage these types of work. The effective communication of the interdisciplinary research and the new/adapted approaches generated to the wider sector will ultimately help to allow these types of artwork to truly live and flourish within the museum.