Introduction

When artworks are conceived of as living rather than static, fixable objects they can gain agency in the decision making process; as philosopher Bruno Latour has said, ‘objects too have agency’.1 The first person to relate Latour’s Actor Network Theory to conservation theory and practice was Vivian van Saaze, who wrote: ‘this particular approach allows me to consider the artwork’s trajectory or career’ and invites ‘a consideration of the constituting role of the museum’, including often overseen actors.2 Reshaping the Collectible: When Artworks Live in the Museum is a three-year research initiative, led by Tate and funded by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, which addresses this proposition of liveness in the collection. The project aims to build capacity for the museum to acquire artworks and represent practices that currently pose a challenge to display, conservation and collection management and in the process to communicate the complex, iterative lives of artworks to the public. One of the questions asked by the project is whether we can trace how it has become possible to collect artworks that were once understood to be uncollectible. As an art historian on the project team, with a background in cultural research and an interest in feminist theory, I have been thinking about how I might address this question by following the life of an artwork. In looking from a historical perspective at moments of change, can we make visible the extent to which the museum has responded to liveness?

This report introduces how I intend to research some of the changes that have taken place in Tate’s organisational structure and museum practices in response to liveness in contemporary artistic practice. I take the establishment of the Modern Art department in 1964 as the historical starting point for my research, a transformative moment in Tate’s history, that took place partly in response to new forms of contemporary artistic practice. Over the next two years I will consider how such changes might reflect parallel shifts in curating, art history and museology. I therefore begin this report by reflecting on the nature of liveness in the context of contemporary art and more specifically how this might connect to, but also expand on, existing histories and approaches to performance in contemporary art. I then outline some of the themes and questions that are currently surfacing from my contextual research into critical theory, curating, museology and art history as well as from my archival research into the project’s case studies and nominated artworks. In this report I consider moments of institutional change through the frame of organisational sociology, using examples of how Tate has responded to artworks at the point of acquisition, and I propose a common thread of informality in programming that runs across instances of change at Tate.

In addition to the question of how artworks might reshape the museum, I am equally interested in the extent to which an artwork changes when it comes into contact with the museum, particularly at the time of acquisition. It might be that a work is categorised in a certain way, or that decisions have been made around the parameters for its display or approaches to its conservation. Since we are addressing how an artwork lives or dies in the collection, I will consider not just the point of acquisition but how a work is reconceived and reconceptualised by the artist(s) and/or museum practitioners at different moments in time. Changes that take place in the museum and changes in an artwork, however minimal, arise out of conversation, ethnographic and archival research, meetings and collective and/or individual decision making. Can these decisions be understood as a dialogue that takes place between artwork, artist and museum, or does the notion of a dialogue remove the power that is already weighted towards the museum?

At the end of the report I reflect on my methodological approach, addressing an ongoing question for me: what role might art historical methods play in this project led by Tate’s Collection Care division? This question connects to a second area of valuable uncertainty for me, around the extent to which I should reflect on my subjective experience. How might my own agency and position – and those of others – help challenge notions of objectivity in the museum?

Liveness in the museum

Museums have been collecting live art since the start of this millennium, but how have practices of performance and live art been disseminated into museum practice and policy? Tate’s curator of performance Catherine Wood has explored how live art ‘forced a change in the museum’s own game’ by challenging existing structures, systems and practices in the museum.3 As such, live art has come to ‘change the ground rules of the institution, its distribution of attention and relations between objects and bodies, and its objectives’.4 Wood writes from her personal experience curating performance at Tate since 2003, a time when it was marginal to the gallery’s ‘main’ activities. In her recent publication, Performance in Contemporary Art, Wood continues to address the notion of subjectivity and agency (drawing on Latour) in relation to the museum: ‘understanding what performance art today means is less about fetishizing liveness as defined by the presence of the living body, as much writing on performance has done, and more about considering a broader state of changeability or instability that is live: to consider how subject and object positions might be destabilised, and how subjectivity and society might be reciprocally shaped.’5 The book looks at performance in the context of international contemporary art from the 1950s and ‘how current practices are rooted in approaches to art that emerged in the first half of the twentieth century’.

Reshaping the Collectible attends to this ‘broader state’ of liveness, exploring the museum’s capacity to respond to ‘changeability or instability’ in artworks as well as in museum and artistic practice. It builds on the foundations of previous Tate-led research projects and is a successor to research into the legacies of performance art at Tate, as well as research into approaches to collecting live art.6 The project has also grown out of conservation-led research into time-based media since the late 1990s.7 As a result of these institutionally inherent perspectives from time-based media and performance in the museum, this project will expand notions of liveness out from performance into materiality and immateriality, notions of precarity, questions around installation parameters, and reflections on temporality and duration. Over three years, six case studies will be selected from a longlist of works from Tate’s archive and collection. This longlist consists of works that have been nominated by individuals across the organisation, based on how they challenge the museum: this might be in the way the works unfold over time, exhibit complex social or technological dependencies inside or outside of the museum, exist in more than one form, or question the institution’s fluctuating boundaries between record, archive and artwork. The theoretical proposition of liveness in this project is connected to duration, to performance and live art histories, and is part of a shift towards notions of performativity.

The use of performativity in contemporary art is rooted in linguist J.L. Austin’s definition of ‘performative utterances’: ‘The term “performative” is derived, of course, from “perform” … it indicates that the issuing of the utterance is the performing of an action … The uttering of the words is indeed, usually a, or even the, leading incident in the performance of the act.’8 Philosopher and gender theorist Judith Butler developed her conception of performativity (from philosopher Jacques Derrida) in reflections on the interior and social constructions of gender and their iterative and ritualistic dimensions: ‘there is no pre-existing identity by which an act or attribute might be measured … a true gender identity would be revealed as regulatory fiction’.9 Clarifying misunderstandings of this increasingly fluid term, art historian and curator Dorothea von Hantelmann argues that what ‘the notion of the performative in relation to art actually points to is a shift from what an artwork depicts and represents to the effects and experiences that it produces – or, to follow Austin, from what it “says” to what it “does”’.10 These applications of performativity through effect, action and the constructions of gender (rather than representation) have recently been extended into curatorial strategies,11 as well as to an institutional self-reflexivity. Catherine Wood, for example, connects Austin and Butler’s notion of the performative to Tate’s response to the programming and collecting of live art. She suggests that the institution acts in performative ways: ‘Performance entering the collection has shifted Tate’s self-understanding about collectability and became a performative moment, in a sense of iterating the possibility and rehearsing the fact of acquiring a Tino Sehgal via a live meeting where nothing was written down.’12 This is where I locate the relation between liveness and performativity in our project; in the way it shines light on the ‘performative moment’ in the life of an artwork, the life of an individual or the life of the institution.

Through paying attention to the live qualities of artworks and their components, this project addresses how much museum practice can change our experience of a work. Liveness might be understood as the liquid transformations in the chemical tubes of Hamad Butt’s 1992 installation Familiars (Tate T14779). When it was included in the Rites of Passage exhibition in 1995 the sublimation of solid iodine in this work led to the evacuation of Tate Britain.13 Does the high level of risk around the control and containment of a work like this limit the duration and regularity of its display at Tate or elsewhere? Searching through the project nomination forms for references to curatorial practice, many are concerned with how decisions are made around an artwork’s display and whether these have the effect of changing the artist’s intentions. For example, when and why do curators and artists come to accept the static display of a live artwork? The display of photographs in The Redwood and the Raven 2004 by Trisha Donnelly should be changed daily but because of the potential risk of deterioration, the photographs are, in fact, changed weekly. Does this decision alter what the artist originally intended? To what extent are curatorial strategies now acquired along with artworks? In a recent presentation to staff, Tate Modern Director Frances Morris referred to an ‘institutional drag or lag’ in collecting practices.14 Is this temporal drag the amount of time it takes something to shift from being considered uncollectible to collectible? What informs curatorial decisions around how often a work can and or should be displayed? And why do some of the artworks commissioned by Tate end up coming into the collection, while others do not? Are these ‘others’ the uncollectible?

Mapping the field(s)

Alongside my research into the case studies and nominated artworks, in the project I will draw upon curatorial studies, museology and theories of institutional change from economics and organisational sociology in order to place these changes in artistic and curatorial practice within a broader theoretical, social and art historical context. In what follows here I outline how these fields, approaches and themes are relevant to the idea of liveness in the collection and to the question of how artworks may reshape the museum by challenging the boundaries and conditions they impose. Current interpretations of curating through notions of care in feminist theory will be drawn on because of the way they help me to address the dominance of the ‘curator-as-author’ in earlier studies and histories of curating.15 Looking at care can bring visibility to hidden histories and practices and is something that feels particularly pertinent to a project located in Collection Care Research. From museology, I look at changes in practice and theory, such as the legacy of what has been referred to as a ‘crisis of representation’.16

Authorship and care in curatorial practice

My research draws on, and hopes to contribute to, the well-historicised evolution of curatorial practice by exploring the way that Tate curators have responded to so-called challenging artworks in the collection. I will explore whether changes in the approach to collection displays and exhibitions can be understood in relation to the professionalisation of curatorial practice from the 1990s onwards. For example, what effect did the canonising of ‘landmark’ exhibitions, from the early 1990s onwards, have on attribution practices at Tate? Are we still feeling the effects of an ‘educational turn’ in curating around 2008? What might the expansion and critique of Nicolas Bourriaud’s relational aesthetics, or the current alignment between activism and curating, have brought to Tate’s collecting priorities and curatorial approaches? I will also address how the collecting of performance or live art may have changed curatorial practices by using specific examples from the project.

In mapping the field of curatorial practice, it is evident that the authoring of exhibitions has played an important role in shaping the discipline and the ‘exhibition as a medium’.17 It is in telling the history of an individual curator or collaboration that we come to understand artistic and curatorial practices in greater depth through relationships, social networks, and political and technological contexts. Curator and writer Paul O’Neill captured this in his phrase ‘curator-as-artist’.18 Similarly, Nathalie Heinich and Michael Pollak have argued that with the increase in temporary exhibitions and growing specialisation, the exhibition became ‘an object in and of itself’ and the curator became an ‘author’.19 The authors describe the movement from ‘museum curator to exhibition auteur’, p.237. From the 1990s onwards histories of curating gained momentum, according to O’Neill, at ‘a moment of emergency when curatorial programmes had little material to refer to by way of discourse specific to the curatorial field’.20 Writing histories of curating was partly therefore a move to prevent the loss of the profession.21 However, emphasis on the ‘curator-as-author’ in curatorial studies has simultaneously had the effect of hiding the less visible ‘re-productive work’ taking place behind the scenes.22 Curator and educator Nora Sternfeld refers to this activity – the mediating of educators for example – as the important but ‘unglamorous tasks’ of practice.23 Paul O’Neill and Mick Wilson, the editors of Curating and the Educational Turn (2010), are guilty of this when they refer to an emphasis on the ‘“processual” rather than “procedural” or instrumental’, stating that ‘curating may not be reduced merely to the administrative, the managerial, the exhibitionary, the spectacular or the thematic co-ordination of disparate or convergent works’.24 Although I can see the problem of fragmenting practice, it begs the question, who is it that does the administration or manages the project, and why are these histories less relevant? The invisibility of so-called ‘unglamorous’ or ‘tedious’ tasks in earlier curatorial histories is an indication of the hierarchies of knowledge in the museum. While there is a current drive to reconsider where these hierarchies lie – as there is in other European and North American museums – it is worth exploring where the effects of this hierarchy are felt so that we might unlearn them.25

Fig.1

The ‘Dimensions of Care’ workshop, led by Elke Krasny, Hannah Wallenfells and Soft Agency, during The (Un-)Learning Place at the Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin, 9–13 January 2019

© Catherine Sarah Young

Fig.2

The (Un-)Learning Place environment, designed by Raumlaborberlin

Photo: Raumlaborberlin

There are challenges to the ‘curator-as-artist’ or ‘curator-as-author’ currently coming out of feminist theories of care. These can provide insight into structural hierarchies that might lie within authoring practices in curating, as well as how they are experienced in museums like Tate. In January 2019 I attended The (Un-)Learning Place workshop – a gathering of ‘foreigners’ at the Haus der Kulturen der Welt in Berlin which marked the start of their New Alphabet School. As part of the ‘Spaces of Theory’ track,26 Elke Krasny, Hannah Wallenfells and Soft Agency (architect Rosario Talevi and curator Gilly Karjevsky) led a session called ‘Dimensions of Care’. Within this, Krasny, a curator and cultural theorist, reminded the group about the etymological roots of the word curating in the Latin curare, meaning ‘to take care of’, as well as ‘to cure’. She spoke about the value of considering care in our lives and work; Karjevsky followed by leading us into a silent conversation.27 For me, recognising how care is so much part of daily life highlighted what is valued – and what is not – within professional environments. In her article titled ‘Caring Activism’, Krasny articulates what she sees as a need for the museum to recognise its role in assembly – as a space for and of activism – and to reconnect to the idea of caring for a collection.28 This, she proposes, is an important step towards ‘decolonising and depatriarchalising the museum’.29

This move seeks to connect care, curating’s literal core, more strongly with its contemporary practice by drawing on feminist care theory that emphasises the ontological and political levels of co-dependence and interrelatedness between non-humans and humans, in our case objects kept in museum collections and members of the public visiting museums. This serves to counteract the strongly held belief that care as invisibilised and feminised labour does not yield aesthetic and intellectually relevant production, which has led to the suppression of the literal meaning of care in the contemporary understanding of curating as outlined above in the short historiography of the curator-as-carer to the curator-as-author.30

How Krasny articulates the invisible, feminised labour in the museum is evocative of the conservator’s practice, or someone or something carefully digitising an archive collection. Her approach is drawn from Berenice Fisher and Joan Tronto’s proposal for a feminist theory of care, and their four intertwining phases: ‘caring about’, what drives your compassion; ‘taking care of’, the action to look after; the close work of ‘care giving’; and ‘care receiving’.31 Against the household and community, marketplace and bureaucratic structures, Fisher and Tronto propose that we think about the feminist ideals of motherhood, sisterhood and friendship.32 Tate is a bureaucracy, with close ties to the market, and the effects of these structures can perhaps be felt in the drive towards consensus. In bureaucracy, as Tronto and Fisher point out, caring in bureaucratic structures ‘is considered just and equal … when it fulfils its rational functions’.33 As a consequence, things that do not fit into existing forms, standards, routines or models can be rejected or hidden. How might we draw on feminist ideals to think through and challenge what is being ‘precluded’ or ‘rendered invisible’ from Tate’s internal and external communication of information, ideas and research, particularly about artworks which challenge the museum?

Despite current recognition in the value of research and learning in museums,34 critical pedagogical practices and their histories are still affected by hierarchies of knowledge in the museum and so can be seen to represent Krasny’s notion of ‘feminised labour’. This is a position Alexandra Hodby shares in her thesis on the learning approaches within Public Programmes at Tate Modern, arguing against the ‘side-lining’ of learning from curatorial histories and texts on ‘New Institutionalism’ (a practice prevalent from the mid-1990s to mid-2000s, initiated and written about by curators, which set out to challenge traditions in arts organisations through the closer integration of education and exhibitions). She does so by giving examples of where Tate’s learning and education practices have ‘pav[ed] the way for curating innovative programmes in terms of media and working with artists’ and where ‘Tate recognised the powerful gesture of including participating publics in museum activity’.35 In this report I use research and learning as examples, but throughout the project (working closely with my colleagues) I want to consider and find ways to acknowledge the contributions made by assistant curators, co-ordinators, interpretation teams and others; to explore the ‘caring about’ materiality and immateriality that is undertaken on a daily basis by registrars, librarians, archivists, visitor services assistants, conservators, editors and art handlers.36 How might bringing visibility to the ‘dimensions of care’ within an institution like Tate help address the museum’s hierarchies of knowledge?

Research and critique in museology

Throughout the project, as well as exploring shifts in the curatorial, I will draw on museological practice and theory where it has relevance to the life of an artwork and notions of liveness in the collection. Firstly, positioned as I am in Collection Care Research, I want to understand the shifting role of research in the museum, and to consider how this may have impacted curatorial practice at Tate. Secondly, I want to consider how the current focus on the transnational in acquisitions, curatorial approaches, research and programming at Tate, generated and driven by the Hyundai Tate Research Centre: Transnational (launched in 2019), might influence our thinking about the iterative lives of artworks. Changes in museology, the increased focus on research in museums and the present interest in transnational exchange have been, and are, reshaping the museum. In what ways might this come to affect how we perceive the life and agency of artworks in the collection?

The ‘new’ approach to thinking about museums that was a result of theoretical developments in the 1980s and 1990s37 was conceived of as a move away from the ‘how to’ of governance and administration that was representative of old museology, and towards the theoretical and humanist discipline of new museology.38 According to Sharon Macdonald, this new approach would reveal how museums are ‘a space of violence, economy, discipline, and police’.39 Rather than see the inherent value of objects in collections, as was the way of old museology, the new museology focused on a critique of representation, identifying how knowledge was produced, as well as what and who was being excluded from exhibitions, collections and audiences in the process. This questioning of representation was a way to address how the exclusions in museums mirrored exclusions taking place in society. According to Macdonald, one effect of this focus on criticality in new museology was the way it helped theory and research play a more central role within museums. There was ‘a greater openness on the part of museums and museum staff to engage with those who study museums but who do not necessarily work in them.’40 This coincided, in the UK, with an increase in funding for research in museums.41

In 2006 research at Tate was formalised when the organisation applied and secured status as one of the Arts and Humanities Research Council’s new Independent Research Organisations (IROs; an AHRC strategy for supporting and sustaining research in museums, galleries, libraries and archives).42 As a result a new Research department was created at Tate in 2007.43 One of the first projects to be initiated was Tate Encounters: Britishness and Visual Culture,44 led by Andrew Dewdney, David Dibosa and Victoria Walsh. Based in the context of Tate Britain and the Public Programmes division, the project drew on ethnographic research to address the ‘art museum’s relationship to global migration and the new media ecologies’.45 In Tate Encounters the term ‘transnational’ was used as a way to capture the effects of global migration and digital circulation on historic notions of national and international borders. Co-investigator on the project David Dibosa was also a founding member of the Research Centre for Transnational Art, Identity and Nation (TrAIN) at the University of the Arts London, founded in 2004, which applies transnational as ‘a definition of cultural interaction that does not automatically presuppose unequal power relationships. Traditional theories, such as Edward Said’s Orientalism (1978), often focussed on an East/West dichotomy. This was a new approach with transnational providing a model which was more flexible than national or international, and where borders are both porous and complex.’46 In 2017 TrAIN held a conference in partnership with Tate Research Centre: Asia called ‘Transnational Cities: Tokyo and London’ (29–30 September 2017) in which the transnational was explored. In 2019 Hyundai Tate Research Centre: Transnational was launched and the notion of transnational exchange is now impacting acquisitions and programmes.47 Tate has been reshaped by the transnational (something that has one foot in museum-based research), but can we explore where the transnational impacts decision making and retrospective critique of Tate’s historical catalogue texts, and in what way this might affect the mediation of liveness and life in the collection.

Institutional change

Tate has been collecting live art since 2005. The first live artwork to be acquired in 2005 was Roman Ondak’s Good Feelings in Good Times 2003 (Tate T11940), followed in 2005 by Tino Sehgal’s This is propaganda 2003 (Tate T12057). Gradually this area of practice has become a priority for the collection and its displays: Tate now has the largest collection of live and performance works in the UK and in 2019 launched a Performance Activation Fund in order to ‘bring to life’ the performance works in the collection.48 Tate’s ability to show, collect and care for live art has been made possible thanks to expertise in the curatorial department and has built on the establishment and growth of time-based media conservation at Tate. As Pip Laurenson, Head of Collection Care Research at Tate, outlines in her doctoral thesis, Tate first appointed a dedicated conservator of time-based media (within Sculpture Conservation) in 1996.49 Laurenson aligns her appointment as Sculpture Conservator for Electronic Media in 1996 to the increase of time-based media works, mostly video installation, coming into the collection in the 1990s. These were ‘almost exclusively editioned and unique works and being sold via the gallery system to Tate’50 and were ‘already demanding high prices’.51 Because of this, the same level of care and attention given to other works in the collection was needed for time-based media works. Today, the time-based media conservation team is one of six teams in the Conservation department and has fourteen members of staff. The development of this team, led by Louise Lawson, was a conservation response to the shifts in curatorial and collecting practice as well as to the new possibilities for display afforded by changes to Tate sites in 2000 and 2016.52 While such large changes – the moment the first live artwork came into Tate’s collection, or the start of the time-based media department with an appointment in 1996 – are critical junctures, I want to suggest that we also explore the more subtle, incremental and discontinuous changes.

Political scientist Kathleen Thelen describes how critical junctures entice as turning points, as moments of innovation or transformation, but they can also obscure more subtle adjustments that take place over a longer period of time.53 Such moments of innovation at Tate include the establishment of the Modern Art department in 1964, or the change in approaches to display in 1990. Soon after arriving as Director in 1989 Nicolas Serota decided to renovate the galleries, reorganise staff and rehang the collection. Past, Present, Future (1990) was the first rehang of the collection and introduced new annual changes to the display.54 What Catherine Wood sees as the ‘eventisation’ of the museum55 indicated, according to art historian Frances Spalding, a new commitment to contemporary art and a ‘desire to unsettle or destroy the assumption of an institutional review’.56 The opening of Tate Modern in 2000 is certainly a critical juncture, as is the opening of the Blavatnik building in 2016. These both afforded shifts in the curatorial and collection care-based approaches to the collection,57 as did the re-display of the collection in 2006, which retained the sequence of themes,58 while replacing the ‘single, institutionally authored history’ with ‘different viewpoints and different framing devices, both in the works and in their dispositions and presentation’, aiming to reflect ‘on history from the present day’.59

These changes appear in histories of Tate as well as in art historical narratives.60 According to Thelen, an alternative approach might be to analyse change and evolution in institutions through ‘feedback mechanisms’ as well as the frameworks to which an institution frequently returns.61 Thelen suggests that ‘feedback processes that sustain [institutions] will provide insights into what aspects for institutions are renegotiable and under what conditions’ as well as what aspects are not renegotiable ‘and under what conditions’.62 By exploring feedback processes and continual returns taking place in an institution, we can analyse ‘what disrupts this and opens up possibilities for change’.63 According to Thelen, change can take place when new processes or arrangements within an institution are layered onto pre-existing structures,64 or when ‘institutions designed with one set of goals in mind are redirected’ and converted ‘to other ends’.65 As Thelen points out, a framework of ‘conversion’ and ‘layering’ enables exploration into the way agencies that were previously excluded might have in fact been incorporated into ‘a pre-existing institutional framework’.66 In particular, and with relevance for Tate, we could analyse the changes that are or were ‘unfolding on the periphery’.67

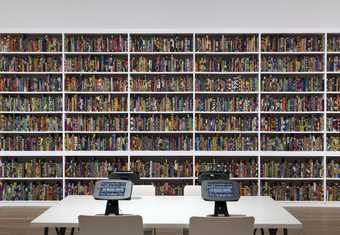

Fig.3

The homepage of the ‘Intermedia Art’ website, www2.tate.org.uk/intermediaart, accessed 1 October 2019

So far in my research into the nature of liveness in Tate’s collection histories, it appears that play, disruption and informality are key agents of change in programming and infrastructure. Where there is a gap in programming there is potential to try something different; where there is a lack of knowledge around artistic practice, there are opportunities for less established members of a team to be given more autonomy. A perfect example is the net art works commissioned by Tate between 2000 and 2011 – a project that was led by the new Digital Programmes team, rather than the curatorial department. A lack of general knowledge about digital practice, combined with a curatorial focus on launching the new displays at Tate Modern, meant that the commissions could be spearheaded by a smaller department with more nomadic flexibility; this arguably enabled artists to take greater risks. Through this project, using the net art commissions as one example, I ask: what are the roles of informality, risk, disruption and play in creating change, and how can we describe the moment just before practices become formalised? Below, I give four examples of responses to gaps in the exhibition schedule and gaps in knowledge and then analyse these, applying theories of institutional change.

The audio-visual library collection

Fig.4

Installation images of the exhibition The Video Show at the Tate Gallery, 18 May – 6 June 1976

Tate Archive Photographic Collection

© Tate

From the mid-1960s, at the same time as conceptual artworks were being acquired – or fought for – by the Modern Art department at Tate, it became evident that there was a growing public appetite for performance, film and video. While staff had been ‘privately studying audio-visual material in the lecture theatre, they found they were “accruing audiences” from the visiting public’.68 Terry Measham, who worked with Michael Compton in the Exhibitions and Education department, produced a report suggesting some of the ways the department might respond to this growing interest and improve access for audiences to film and performance in the gallery.69 One suggestion was to form a library of films, including ‘films that are Art, intentionally; films about Art – including events by artists in or outside the gallery; and films on topics related to the study of art: optics, light, colour, energy, other aspects of the psychology of perception including the motivational side, social psychology, history, literature’.70 Measham’s proposal for an audio-visual library collection was realised and the collection was shown at screenings in the lecture and theatre room. It also served as a resource for lectures. There is a sense of informality in the way the library collection formed, as is captured in Measham’s comment that retaining the film library within the department would avoid the ‘acquisitions machinery since copies of films are sold in the normal way without claims to any intrinsic value in the celluloid strip itself’.71 With this freedom there was also greater potential for collaboration across the Exhibitions and Education department and new approaches to programming. The Video Show in 1976, organised by Simon Wilson (Lecturer at Tate) with technical assistance by Cliff Evans (a video-maker, who was part of the video group TVX, a sub-group of the Institute for Research in Art and Technology),72 presented an installation work over one week in the gallery’s lecture and theatre space.73 However, as seminal figure in history of British avant-garde film and video David Curtis has recently recalled, there were complaints about this marginalisation: ‘throughout the 1970s and 1980s the only displays of the artists’ moving image at Tate were those staged in gloomy basement lecture rooms – generally initiated not by the Tate’s curatorial team but by its education officer Terry Measham’.74

Interval exhibitions

Fig.5

Charlie Hooker’s Behind Bars 1981 being performed during Performance, Video, Installation at the Tate Gallery, 22 September – 11 October 1981

Tate Archive, Photographic Collection

© Tate

Fig.6

The lounge environment in Audio, Tape-Slide, Drawings and Performance at Tate, 23 August – 8 September 1982

Tate Archive, Photographic Collection

© Tate

In the 1980s a series of three exhibitions took advantage of gaps in programming to bring performance, sound, video and installation into Tate’s exhibition programme. This type of exhibition was defined in an Annual Report as follows: ‘A different category of show, which is not entirely new to the Tate, has been undertaken on a new scale of determination and enterprise. This is the occasional showing of artists using performance, slides, film, sound tape and other media as well as or apart from the traditional media. These have been fitted into galleries during the period between the larger shows.’75 The first of the three exhibitions was Performance, Video, Installation (22 September – 11 October 1981), which took place between David Jones and Ceri Richards (both 22 July – 6 September 1981) and Patrick Caulfield (28 October – 3 January 1982). The exhibition, organised by Catherine Lacey, Richard Francis and Richard Calvocoressi, included a programme of video art,76 the first display of Tim Head’s Displacements 1975–6 (Tate T02078; acquired by Tate in 1976 and the first artwork in Tate’s collection to be categorised as installation), Marc Camille Chaimowicz’s installation and performance Partial Eclipse 1980–2006 (Tate T12453), retrospectively acquired in 2007, and Behind Bars 1981 by Charlie Hooker, performed by members of Newcastle’s Basement Group. The second ‘interval’ exhibition, as Richard Francis referred to it, was Audio, Tape-Slide, Drawings and Performance (23 August – 19 September 1982).77 This exhibition focused on artists working with sound and included a lounge environment with the archive of Audio Arts, Ian Breakwell’s 120 Days 1981 (Tate T03936–T03938), work by Gerald Newman and a performance by Sonia Knox. The third and final exhibition in the series, Performance Art and Video Installation (16 September – 6 October 1985), selected by Keith Skone, Catherine Lacey, Richard Francis, Jeremy Lewison and Ann Jones, included works by Dara Birnbaum, Rose English (whose work Quadrille 1975, 2013 (Tate T14673) was acquired in 2016), Nan Hoover, Anthony Howell, Marie-Jo Lafontaine, Hannah O’Shea and Silvia C. Ziranek. One-off performances and film-based or multimedia exhibitions were programmed between and after these exhibitions, including British Film and Video 1980–1985: The New Pluralism, curated by Michael O’Pray and Tina Keane (11–28 April 1985). All were presented in the lecture room rather than the galleries.78

Programming, archiving and conserving audio-visual material

The series of public performances and exhibitions mentioned above developed new expertise at Tate in performance, video and installation, in large part because of artist participation and collaboration. At the same time discussions were held at Tate on the best way to represent performance, film, video and slide material in the future. It was clear that there was a gap in knowledge about how to programme this kind of material, whether it should be collected at all, and which departments should be responsible for its ongoing care. The conservation and preservation of films and video had become a particular issue. An Audio-Visual (AV) Committee was established in 1984 by the Education department to consolidate information about audio-visual material from across the institution and to address issues of expertise and resourcing. The committee, chaired first by Michael Compton and then curator Catherine Lacey (when Compton left Tate), aimed to understand the status given to film and video by different departments. To address this, they looked at whether film and video should be bought or hired in and addressed the question of expertise within the institution and how this could be developed. In minutes from the AV Committee meeting on 18 December 1986 it was noted that the Modern Art department collected AV media ‘on an ad hoc basis. Most were installations and could be exhibited in ordinary galleries’; the Library ‘collected certain AV items as documentation and for reference’; and the Archive (founded in 1970) ‘had off-cuts of films’ and ‘made taped interviews’, while ‘others were occasionally bought or given as were video tapes’.79 Exhibitions and Education (which were two separate departments until 1980) had amassed a collection since the 1970s (as mentioned above) following performances or screenings, and it was unclear what status this material should have and whether Tate had any right to the material. Reading through these notes, it is possible to see how the boundaries between departments were blurred from the start when it came to film and video.

At least one work from the collection was transferred to the library around this time: Eurasienstab, Fluxorum organum opus 39 1968 (Tate TAV 1623F), a film by Joseph Beuys with music by Henning Christiansen, was acquired in 1974, around the same time that discussions were taking place about the possibility of acquiring Beuys’s Eurasia Siberian Symphony 1963, 1966, an installation comprising a chalk drawing, felt, fat, a taxidermied hare and painted poles that had resulted from the performance at Galerie René Block, Berlin in 1966.80 Although this was rejected (Norman Reid saw the Eurasia Siberian Symphony as equivalent to ‘the costume of the pantomime horse in “Parade” after the dancers have gone’),81 in 1974 Tate acquired Eurasienstab, a film of a performance by Beuys at Wide White Space Galley in February 1968, with music by Henning Christiansen and camerawork by Paul de Fru.82 The film, however, was later transferred to the Education Department film library in 1979, with the justification that the department had technical expertise in film and video as well as already holding other films by Beuys.83

AV Committee meetings continued up until 1989, by which point Catherine Lacey and Beth Houghton (Head of Tate Library and Archive) had produced ‘Audio-Visual Issues in the Tate Gallery: A Discussion Document’ (31 August 1988),84 based on a discussion document Lacey and Houghton had circulated among staff. This addressed the lack of communication between departments on acquisitions; ‘scattered and extremely inadequate’ storage; ‘insufficient’ equipment; lack of space for screening and display; little funding for production and acquisition; ‘insufficient staffing’ in all areas for this medium; a need for procedures concerning copyright and licensing; and potential issues in the future given the ‘fugitive nature’ of the media and problems of ‘compatibility and future obsolescence of systems and play-back equipment’.85 One of the things Lacey and Houghton were trying to establish through inter-departmental consultation was whether it would be better to centralise AV items in the collection, library and archive (including recordings of events at Tate) and associated knowledge, skills and equipment, or whether these items should be separated by department as they were at the time. It appears to have been decided that each department should be responsible for the decisions around which materials, artworks and records came into the library, archive or collection. In other words, at this point they remained scattered.

‘Live at the Tate?’

As Tate’s interest in performance persisted, a Performance Sub-Committee was established in 1989. At the first meeting (attended by Catherine Lacey, Curator, Richard Humphreys, Curator of Programme Research, and Ruth Rattenbury, Head of Exhibitions) it was agreed that their working definition of performance was any ‘live’ activity, including ‘performance art, dance, drama, readings and music’.86 The discussion was not around acquisitions but how, where and in what way Tate could continue to show performance, with the proposed title ‘Live at the Tate?’.87 In what appears to be the only meeting of the Performance Sub-Committee, they recognised the need for performance art events to be ‘treated as exhibitions’.88 In my research I want to understand how these conversations developed over the 1990s, whether the discussions moved to departmental meetings, and what connects this committee to the appointment of Catherine Wood in 2003 as Curator, Exhibitions and Displays, Tate Modern.89

Conversion, dissensus and ‘new pressures for change’

In these examples of change through informal programming, knowledge and exhibition gaps, committees and sub-committees, performance appears to enter discussions a number of times. We could say it is sustained through the ‘feedback mechanisms’ of the AV Committee and the Performance Sub-Committee. Though the committees were not sustainable long-term, funding began to appear from 2002 to support the development of performance in the collection. In the 1970s and 1980s performance was marginal in the museum and remained that way throughout the 1990s, but at some point it converted the institutional structure and redirected the institution’s goals. Another more recent conversion might be the increased acquisition of works by indigenous artists since the collaboration between Tate and the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, funded by Qantas.90 As a new reach for the museum, what conflicts ‘over the goals and purposes’ of the museum were opened up and did this introduce ‘new pressures for change’, to use Thelen’s words?91

Over the next two years I aim to apply theories of institutional change to analyse subtle and incremental shifts at Tate, exploring the increasing returns and feedback mechanisms that have led to changes in acquisition and disposal policy. I am also interested in drawing on sociologists Paul DiMaggio and Walter Powell’s analysis of isomorphism: ‘the constraining process that forces one unit in a population to resemble other units that face the same set of environmental conditions’.92 Isomorphism is a homogenising process that is exerted on professions from ‘formal education and of legitimation in a cognitive base produced by university specialists’ as well as through ‘the growth and elaboration of professional networks that span organisations and across which new models diffuse rapidly’.93 Resistance to isomorphism comes from diversity and variety, yet when we look to implement change in bureaucracy (as we see with Fisher and Tronto) we try to gain consensus, so what then is the place and potential of dissensus, of informality, risk, disruption and play?

Case studies

Thus far in this report I have introduced the conversations that have been held around a desire to show performance and the ad hoc collection of time-based media. I have also explored liveness in the museum and its connections to histories and practices. Another part of my interest lies in how an artwork is conceived of and at times changed or reshaped by the museum, and vice versa.94 Below I introduce two case studies that I will analyse in my research over the next two years. The first speaks to change in relation to artistic intention, while the second appeals to questions of visibility, and looks to the potential for institutional self-reflection, something that is enabled through questions of liveness and performativity.

Paul Neagu’s films

Fig.7

Documentation of Paul Neagu’s Cake-man Event at the Sigi Krauss Gallery, London, 10 May 1971

Tate Archive

© Andrew Tweedie

Between 2000 and 2002, sculptures, drawings, films, sketchbooks, photographs and notes by Paul Neagu were acquired by Tate, joining two works already in the collection: Rocking Hyphen (Edge Runner) 1983 (Tate T05032; acquired in 1988) and the watercolour print Jump 1977 (Tate P07259; purchased in 1979, following the Paul Neagu exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, London). During the process of selecting the works, beginning in 1998, it was unclear whether the five films by Neagu should be considered as artworks or documentation, and therefore whether they should be cared for by Collection Management and Conservation or by Library and Archive. In conversation with Neagu, who was unwell at the time, it was decided that Neagu’s Boxes 1969 and Going Tornedo 1974 were artworks ‘in themselves’, while Blind’s Bite 1975, Hyphen Ramp 1976 and Cake-man Event 1971 were documentation, but precise evidence of this is hard to find. The Board Note, written by Paul Moorhouse and dated November 2000, stated: ‘Two of the films – Neagu’s Boxes and Going Tornado – are regarded by the artist as works of art in themselves. The remaining three films provide a record of exhibitions and performances but are not seen as artworks per se.’95 Yet the subsequent sentence in the Board Note immediately contradicts this comment: ‘the earliest, Neagu’s Boxes, is a record of an exhibition of boxes held by Neagu in Bucharest in 1969’. Internal correspondence between Curatorial, Collection Management and Conservation shows the lack of certainty about this decision. Pip Laurenson (a time-based media conservator at the time) wrote in an email to Paul Moorhouse dated 15 June 2001: ‘the Collection has not really included documents of performances before (apart from Rebecca Horn) and this seems to be a new area of acquisition activity and hence curatorial input would be particularly valuable’.96 The issue of the split between collection and archive is evidence of blurred boundaries and shifts in priorities. Would the works be acquired in the same way today? What has been the effect of categorising these works into the institution’s structures in this way? Can and should they be re-categorised?

Sutapa Biswas, Kali 1984–5

Fig.8

Sutapa Biswas

Kali 1984–5 (still)

Video projection, colour and sound

© Sutapa Biswas. All rights reserved, DACS 2019

Fig.9

Sutapa Biswas

Kali 1984–5 (still)

Video projection, colour and sound

© Sutapa Biswas. All rights reserved, DACS 2019

The film Kali 1984–5 (Tate T14278) by Sutapa Biswas was presented to Tate in 2012, along with Untitled (The Trials and Tribulations of Mickey Baker) 1997 (re-edited and re-mastered in 2002; T13978). Later, when a second version of Kali was accessioned (the version shown at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, London), Tate also acquired To Touch Stone 1989–90 (Tate T15041), a large-scale drawing by Sutapa Biswas of a reclining naked woman (the artist’s sister). Kali captures a performance of the same name by Biswas and Isabelle Tracey at Leeds University while they were both students. Biswas and Tracey perform as themselves as well as Hindu deities. An unsuspecting Griselda Pollock, who ran the ‘Theories and Institutions’ course at Leeds University at the time, was brought into the performance. Through the work Biswas questioned occlusions from art history and theory and, with Tracey, performs multiple roles as a way to explore and make visible experiences of race, subjectivity and identity. Kali was accessioned in 2018 and has yet to be shown at Tate. There are also different versions of the work, which has created some confusion in the past. The version that was shown in the Thin Black Line at the Institute of Contemporary Arts (1985), is shorter, and includes an introduction by Biswas; the other is a longer, ‘raw’ version. Firstly, by exploring the contexts in which the different versions have been shown and historicised, including at Tate, I hope to address how we might care for the iterative nature of artworks. Secondly, with this work as an example, I want to raise broader questions about visibility and invisibility by asking: what leads to and informs decisions around collection display?

Methodology

I aim to approach the questions and ideas outlined in this report through a combination of empirical research and contextual analysis. Shifts in art history, curatorial practice and museology will be important, but given the transdisciplinary nature of the project, I will also draw on economics, ethnography, technology studies and organisational sociology, in order to analyse and historicise liveness in the museum.

In this report I have introduced the gaps or intervals in programming, and the play, informality and dissensus that can be indicators of institutional change. Rather than simply addressing transformative moments, I am interested in the agents and processes that create, or restrict, incremental and subtle changes. I have introduced two examples of artworks from the project that will be a focus for my research: Paul Neagu’s films and Sutapa Biswas’s Kali. These two examples allow an analysis of the dialogue that takes place between artist and museum where changes surface as a result. Neagu’s films still hold a confused status in the museum; we could even say the museum redefined the artist’s intentions by locating three of the films in the archive. In the case of Kali, in what ways does this work trouble visibility and invisibility in the collection? By looking at how Neagu’s work was acquired, I intend to address how performance has become more familiar within the acquisition process. By showing the unfolding life of Kali in the institution, I will explore questions of visibility in the collection.

I have raised questions around what it means to address the living quality of a work and stated my intention to develop this from an art historical perspective, addressing the shifts in representation. This will be informed by the rising value of performance in contemporary art, but it will also be connected to transnational histories and identities. The historical period when performance art became more collectible – 1970s to the present day – mirrors the trajectory of postcolonial studies and decolonisation; it also mirrors shifts in feminist approaches to art history. In my exploration of the process of de-patriarchalising and decolonising I will draw on feminist approaches to art history.

Throughout the project I will address my own position, including what my role as an art historian within the project means, and the problems and possibilities it brings. I will continue to think through the relevance of art historical methods in addressing questions that come from collection care research.

Conclusion

The questions around how an artwork lives, unfolds, oozes out, decomposes, recomposes, becomes invisible, is forgotten or takes centre stage in the museum collection force us to think about creating change in museum systems and practices to better accommodate their sometimes messy and unpredictable lives. These questions also encourage us to look historically at how a continually reshaping museum might have changed our experience of artworks. In my research around the proposition of liveness, I aim to contribute to the fields of art history, institutional history and curatorial studies a greater understanding of where the effects of time-based media and performance practice might be felt.

There is no doubt that a work changes when it comes into the collection, but perhaps we sometimes lack clear understandings of how, why and in what ways decisions that have been made about a work have created this change, and what theoretical knowledge, methods or practice-based histories have informed these decisions. While conservation is open to critique, we should also be developing the tools and the confidence to interrogate curatorial decision making. My research hopes to open this up through a historical study that looks at one of the most (if not the most) important tasks of the curator – to mediate between the artwork, with its shifting contexts, and the public. How is this process moving, shifting and changing, and how are curatorial decisions changing the artwork itself?