William Tucker

Anabasis I

(1964)

Tate

Plastic as a material

We often think of plastic now as a problem. But when the first man-made, malleable and mouldable materials were invented, artists quickly saw the potential. Plastics could be moulded or folded or cut with ease, so they offered exciting new possibilities for sculpture.

Sculptor Naum Gabo felt that artists should use these new materials to bring the ‘constructive thinking of the engineer into art’.

However, artists soon found that some of these plastics were in fact unstable and quickly deteriorated. The celluloid acetate Gabo used for a 1936 version of this work had begun to warp and crack by the 1960s. Gabo thought this was down to the conditions it had been kept in. It’s now accepted though, that this type of plastic will always lose its flexibility over time, and end up cracked and shattered.

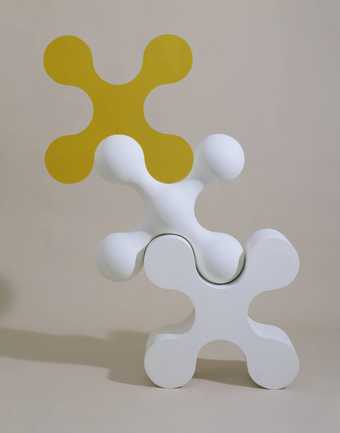

Philip King also used plastics in his large-scale sculpture. He originally made this work in plastic and fibreglass in 1963, but later discovered that fibreglass tends to distort and mark in large surfaces like this. So he remade the sculpture in 1971–2; still of fibreglass, but supported on a steel frame to prevent the distortion of the fibreglass shell.

Phillip King

Genghis Khan

(1963)

Tate

Other artists embraced the idea that artworks might destroy themselves.

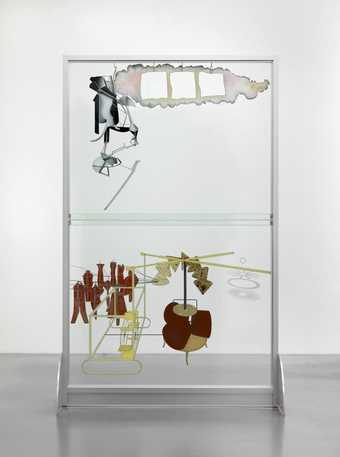

In 1959, Gustav Metzger produced a manifesto describing his idea of auto-destructive art. Metzger believed society was placing a dangerous level of faith in mechanically-produced objects. He wanted to show that even these man-made objects would break down in the end, and humans would have no control over it. He felt that making works which destroyed themselves would highlight society’s obsession with destruction and the damaging effects of machinery on human life.

In this public action work from 1960, Metzger painted a hydrochloric acid solution onto a large glass pane covered with a Nylon (synthetic fibre) fabric. As the acid came into contact with the fabric it immediately dissolved it. It left a swirling gluey coating on the glass, through which Metzger and his paintbrush slowly became visible.

Gustav Metzger

Recreation of First Public Demonstration of Auto-Destructive Art

(1960, remade 2004, 2015)

Tate

Plastic Abstraction

Some artists used the perfectly flat surfaces and colours they could achieve with plastics to make abstract works. Plastic allowed artists to play with shapes, forms and flat colours in three dimensions, not just on flat canvases. In the late twentieth century, some artists became interested in minimalism in art. They thought artworks should have their own reality and not be an imitation of something else. Many of these artists used plastics to create totally non-representational art.

Plastic Bodies

Other artists use plastics in the opposite way – to make hyper-real art. Ron Mueck’s silicone and fibreglass sculptures look startlingly realistic apart from their scale. They are either much larger or much smaller than real life. This makes you look at something familiar in a new way.

Louise Bourgeois also presents uncanny bodies and body parts. In Mamelles the soft squashiness of synthetic rubber suggests living flesh. (It doesn't really look like flesh, but gives you that creepy feeling that it somehow might be).

Louise Bourgeois

Mamelles

(1991, cast 2001)

Tate

Plastic and everyday life

Unlike natural materials, plastic come in bright, flat synthetic colours. By the mid 20th century, coloured plastic bottles, buckets and tubs were in every shop and every home. These colours changed the way we saw the world around us, especially in urban environments. Once plastics stopped being ‘new technology’ and became part of everyday life artists began to see plastic items in a different light.

Prunella Clough photographed all sorts of garish plastic items outside shops. She noticed beauty in things that others would just walk past – in their colours, shapes and composition.

Prunella Clough

Colour photograph of plastic buckets stacked up underneath a shop window

([1990s])

Tate Archive

Prunella Clough

Colour photograph of brooms, mugs, dusters, and other merchandise arranged outside a shop

([1990s])

Tate Archive

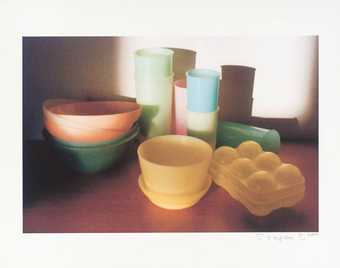

Others, like Jane Simpson, found a sense of domestic nostalgia in plastic homewares.

Jane Simpson

Sunset Still Life

(2000)

Tate

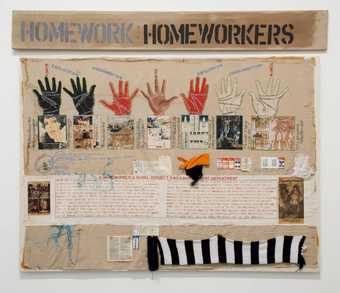

But the domestic is not always a place of cosiness or security. The accumulating plastic rubbish around Tracey Emin’s My Bed points at a time of sadness and depression. Margaret Harrison’s Homeworkers is about the often exploitative labour that takes place in homes. It explores how women in the 70s often did piece work from home but had no workplace rights. Including the rubber gloves pointed out that women often also bear the burden of housework as well as 'home work'.

Plastic is rubbish

Seamus Nicolson

Jason

(2000)

Tate

Plastics have never had such a bad name. Plastic no longer represents exciting scientific breakthroughs or a new modern world. Now the impact of throwaway culture, plastic bags and other single-use plastic on our oceans and landscape is finally becoming clear. But artists have been looking at plastic dumped in the environment for years.

Martin Parr CBE

The Last Resort 29

(1983–6, printed 2002)

Tate

Keith Arnatt

Miss Grace’s Lane

(1986–7)

Tate

Keith Arnatt

Pictures from a Rubbish Tip

(1988–9)

Tate

Simryn Gill

Channel #4

(2014)

Tate

Have a go!

A Plastic Portrait

Tony Cragg

Britain Seen from the North

(1981)

Tate

Tony Cragg has often worked with found materials and even rubbish to create his sculptures. He explores his relationship to the natural world and our impact on nature through the materials we discard. While at first glance Britain Seen from the North seems a joyful decorative image, Cragg felt differently. Living in Germany he was unhappy to return to the Britain of 1981. He responded to seeing a worsening economic situation and violence on the streets by creating a portrait of Great Britain from rubbish.

- Choose a place or landscape to represent. It could be somewhere experiencing the impact of plastic pollution, or somewhere you have a strong connection to.

- Experiment with maps, sketches, photographs and drawings to create simplified outlines and forms to work from.

- Collect fragments of plastic or plastic items that are no longer needed. Be careful with the objects you use and where you get them from.

- Expand your outline on to a large scale, on paper, fabric or cardboard.

- Arrange your plastic items in your outline form, thinking about colour and balance and shape.

- Photograph and make sketches from your arrangements.