Assumptions about the indexical nature of the photograph continue to pervade the quotidian visual realm. Examining the truth claim of photography opens up vexed questions around objectivity, representation and the nature of the real. Interested in making the subjective and constructed nature of photography explicit, and working with the photograph as fiction rather than as document, I moved from documentary practice to developing staged collaborative portraits.

Sheba Chhachhi, Arc Silt Dive: The Works of Sheba Chhachhi (2016)1

Location, regional cultural dynamics and placemaking as a process, when collectively analysed, have transformed the grammar of documentary photography in contemporary India. They have led to the questioning of image hierarchies and the privileging of certain visual and archival practices in the subcontinent – whether they be associated with portraiture from the colonial era, or performative photography in the present.2 ‘Location’ is itself a mutable concept in artistic practice today given the ubiquity of digital media in society: across the world, digital universalism has provoked and enabled the rise of micro-histories through myriad interdisciplinary initiatives, such as the ‘moving image’ and the growing presence of oral histories in new media practices. An evolving intersectionality of concepts and aesthetic and critical frameworks has bolstered alternative exhibitionary and artistic practices across regions and communities, and these alternative modes for visual expression and viewership can be traced back to the pre-digital era.3

In Sheba Chhachhi’s early documentary photography of the Indian women’s movement in the 1980s, and her staged images from the early 1990s – which feature in Seven Lives and a Dream 1980–91, printed 2014, and which later coalesced into the installation Record/Resist 2012 – she refracts the imagery of feminist protest in India in order to suggest novel modes of engagement with histories of resistance. Deploying assemblage formats, which include animated light boxes, videos and multi-media installations, she traces social formations and solidarities from the pre- to the post-digital through meticulous study of her subjects and a discursive approach to photographing them. Chronicling the social present, her works have moved further in the direction of public display from the 2000s onwards, partly as a result of the proliferation of biennial culture and installatory practice during that time. They gesture towards radical political commentary and evoke a heightened awareness around notions of subjectivity and shared agency, through an acute consciousness of specific frameworks of marginality and alternative culture in the subcontinent.

Several writers have considered the 1960s and 1970s to be a context-changing moment for the arts – curator Nancy Adajania refers to it as an era of ‘new-context media’ – wherein a melding of new technology and art became a fulcrum for expressing the artist’s position, and enabled a certain public-facing pedagogy through their practice.4 As the art world became more media-aware in the 1990s, with televised incidents such as the Mandal Commission protests and the demolition of the Babri Masjid mosque in 1992, artists like Chhachhi used the installation format to counter the unilaterlism of the press and globalise the context and message of an engaged, resistance-oriented art practice emanating from India.5 In this essay, which is informed throughout by my conversations and ongoing work with Chhachhi, I reflect on the trajectories through which her photographic series such as Seven Lives and a Dream (hereafter Seven Lives) present compelling narratives about the edicts of the gaze, the evolution and entanglement of notions of belonging, and the strident aesthetic of recollection – all of which come to bear on her art through activism.

Early contexts

Chhachhi graduated in economics from Lady Shri Ram College, Delhi University and trained in visual communication at the National Institute of Design (NID), Ahmedabad in the late 1970s. Following this, she co-founded Lifetools along with her colleague Jogendra Panghaal. Lifetools was a research-oriented media organisation committed to socially useful design that worked with and for urban and rural communities, activist groups and peoples’ movements, marking an early moment in the development of Chhachhi’s artistic and activist worldview. Through her subsequent photographic work, Chhachhi has consistently presented a counter to much of what already existed in the heterogeneous field of documentary photography and photojournalism in India during and before her time.

After India gained independence from the British in 1947, an emancipated press allowed for greater journalistic exposure to the country as a subject. Western photojournalists such as Swiss photographer Walter Bosshard and American Margaret Bourke-White, among several others, were sent to capture the paradigm shift in India’s history at this time, disseminating their iconic photographs globally according to differing modes of circulation and varying levels of access to technology.6 However, though several practitioners spent broad spans of time in the region, their interactions with key figures were sometimes limited – often a matter of days – which raises questions as to what extent such journalistic images accurately ‘documented’ or sympathetically articulated the position of their subjects, as was seen in the works of Indian photographers such as Homai Vyarawalla, Kulwant Roy and Kanu Gandhi.7 Many years hence, from the time that Chhachhi began her career in the 1980s and 1990s, a major shift was seen in local photojournalism and its place within the newspapers’ editorial, a shift that perhaps preempted the rise of ‘citizen photography’ and user-generated image content that has become influential in journalism in the present.

Alongside post-Independence photojournalistic imagery, Chhachhi has also challenged the historical genre of ethnographic image making and landscape photography in the country. The earliest examples of these were produced in the nineteenth century and had a deeply homogenising and essentialising tenor due to the colonial gaze of the photographer and the imperial agenda behind their photographic projects.8 To take an example of such critique in Chhachhi’s work, the artist has indicated that her installation Neelkanth: Poison/Nectar 2000–8 (Tiroche DeLeon Collection, Gibraltar) aimed to challenge colonial landscape photography by featuring sepia-toned images of garbage scraps at landfill sites, but also by focusing on the body parts of individuals rather than making a portrait, highlighting the complexities of identity construction.9

Chhachhi’s visual critique of colonial and post-Independence photography has involved building an iconography based on visually and historically entrenched associations using still images – whether they be her photographs of the women’s movement, of the body, of women ascetics seen in Ganga’s Daughters: Meetings with Women Ascetics 1992–2002 and Initiation Chronicle 1998–2002, or her later eco-feminist installations like The Yamuna Series 2005, Edible Birds 2007 and The Water Diviner 2008.10 Chhachhi illustrates how evolving creative strategies, aesthetic productions and collective methods of countering identity imagery can be realised through a prolonged social consciousness and commitment, in order to induce a shift in focus from the ‘native to the citizen’.11 While the ‘native’ was silent and spoken on behalf of, as ‘citizens’ everyone allegedly gets to speak and be counted – a concept that has been challenged in the present by policies such as the Citizenship Amendment Act.12 However, the essential tenet of this shift can be seen in Ganga’s Daughters through Chhachhi’s depiction of nine women ascetics, in which she foregrounds the women’s personal histories and their co-construction of their identities as a way of contesting patriarchal narratives and counteracting the silencing of women’s experience in Indian history.

From her earliest portraits of the women’s movement, Chhachhi developed an ethically informed approach to the very process of creating work and then sharing it within the community. This underpinned her activist initiatives and engagement with vigilant art – art that redeploys the notion of ‘seeing’ or ‘being watched’ by the state machinery – and furthermore demonstrates aesthetic modes she arrived at through the process of affiliation and co-empowerment.13 Chhachhi has described how this approach was nourished by her early exposure to critical media discourse at Chitrabani, Centre for Media Studies in Kolkata that was set up in part by Satyajit Ray.14 Her fellow travellers and associates in the early 1980s were audio-visual media and documentary film practitioners like Avehi in Mumbai and Yugantar in Hyderabad, to name just a few organisations that were producing material for and about women.15

Countering typologies

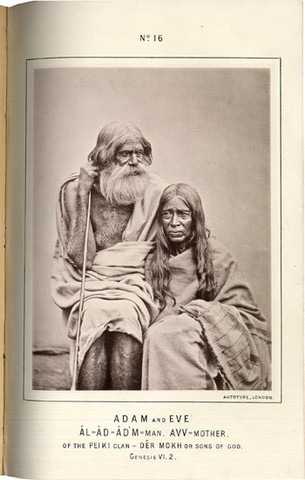

Fig.1

Adam and Eve, from William Elliot Marshall, A Phrenologist Amongst the Todas, Or, The Study of a Primitive Tribe in South India: History, Character, Customs, Religion, Infanticide, Polyandry, Language, London 1873, pl. no.16

Alkazi Collection of Photography, New Delhi

The complicated relationship between cultural and imperial worldviews was exposed in the ideological, institutional and visual practices of colonial organisations across India during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. As numerous scholars have argued – including Stuart Hall, Suren Lalvani, John Falconer, Geoffrey Batchen and Karen Strassler, among others – this was executed unequivocally through portrait photography, which often foregrounded the representation of ‘bodies’ as culturally and racially defined.16 The imaging of a ‘likeness’ became a means of negotiating the interpersonal engagement between the subject, photographer and often a patron, an institution or indeed an administration. In the context of South Asia, such fraught relationships of inequality were further augmented by the addition of descriptive text to images. This was observed, for instance, in the politically charged labelling of ethnographic photographs in the infamous eight-volume People of India album series, and in William Elliot Marshall’s A Phrenologist Amongst the Todas, Or, The Study of a Primitive Tribe in South India: History, Character, Customs, Religion, Infanticide, Polyandry, Language.17 An example is Adam and Eve (fig.1), an ethnographic portrait made in a South Indian community and published in Marshall’s A Phrenologist Amongst the Todas, in which the sitters are reduced to a stereotyped depiction of man- and womanhood, to the exclusion of any visual representation of their specific personal context and history.

The history of photography in India alerts us to how portraiture in particular became a way of straightjacketing impressions through reductive representations of the face, a place or an event. Practitioners, either endorsed by the state or through commercial venture, would use images of community – caste, race and occupational type – to circumscribe and define the audience’s perception of Indian peoples via print media and colonial display. In large-scale global exhibitionary practices in the more recent past, for instance from the 1980s onwards, Raj nostalgia exhibitions became exceedingly popular, as was seen during the Festival of India in the UK in 1990 and a major show at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London in 2009.18 Such exhibitions focused on the princely classes who governed India after it gained independence from the British, retaining the mannerisms and dress associated with the ruling classes. The interest in these histories led to a growth in acquisitions by Indian national institutions and private collectors as of way of retrieving lost historical traces of the subcontinent and countering the dominance of European practitioners in their collections. The late 1980s, for instance, saw major works by Lala Deen Dayal being collected and sometimes donated, hence today residing in the collections of the Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts and the National Gallery of Modern Art.19 However, at the same time, this allowed imperial-era image discourses in India to become institutionalised and canonised as ‘nationalised’ subject matter, a classification that was imbued with a subtly hierarchical, Eurocentric tenor.

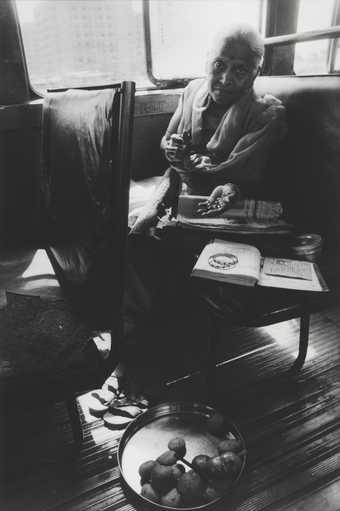

Fig.2

Sheba Chhachhi

Shardabehn – Staged Portrait, DTC bus, Terminus, Delhi 1990, printed 2014, from Seven Lives and a Dream 1980–91

Photograph, gelatin silver print on paper

778 × 518 mm

Tate

© Sheba Chhachhi

Fig.3

Sheba Chhachhi

Sathyarani – Staged Portrait, Supreme Court, Delhi 1990, printed 2014, from Seven Lives and a Dream 1980–91

Photograph, gelatin silver print on paper

772 x 516 mm

Tate

© Sheba Chhachhi

It was around this time, in 1990–1, that Chhachhi invited the seven activists who were friends, sisters and fellow travellers – Sathyarani, Shahjahan Apa, Shardabehn, Devikripa, Urvashi, Radha and Shanti – to collaborate with her on developing a series of staged portraits about the women’s movement in Delhi. Countering notions such as objective truth and questioning documentary strategies adopted by much of the Western photojournalistic canon, Chhachhi focused on recording and relaying her sitters’ own sense of history. As she has described it: ‘Each woman chose a place, a posture, materials and objects that she felt could speak of her and tell her story. Apa brought a small hut, meticulously made from a shoebox, glue, and tinsel paper: “my story is a shanty town story”. Shanti borrowed an axe, spread wheat on the floor, opened her diary. Sharda offers a bus pass, tiffin box, a set of glass marbles’ (fig.2).20 Together, the activists built a mise-en-scène with the photographer across diverse sites in Delhi: the steps of the Supreme Court of India (fig.3), a single-room home in a resettlement colony, and even the inside of a local bus.

The images present the photographer’s meticulous and gradual assurance to the protagonist that their agency will be represented in the final image; as if in recognition of this, the subjects gaze at the viewer with determination, if not defiance. The viewer’s reading of each subject is guided by the careful selection of objects arranged around them as well as the location each subject has chosen. This strategy highlights a historical turn in which the subject becomes the author, which was especially significant in light of the subcontinental history of representation in which women were the sitters for, but rarely the creators of, photographic imagery.21 By clearly inviting and accepting the subject as guide, Chhachhi presents a compositional methodology for activism in which the location and imagery of the citizen is asserted as multivalent, hybrid and emancipated. She does this, for instance, through her use of montage and collage, archival and handmade productions, and by superimposing testimonies onto her portraits in installations such as Record/Resist 2012 and When the Gun is Raised, Dialogue Stops: Women’s Voices from the Kashmir Valley 2000.22 For Chhachhi, such an approach may have been influenced by her interactions with Subhadra, a half-naked ascetic whom she photographed during her NID years in the late 1970s.23 Seven Lives and a Dream could also be seen to resonate with similar community-generated projects taking place internationally; for instance, in Our Faces, Our Spaces: Photography, Community and Representation, members of the South Asian diaspora in the British city of Southampton produced photographs of their own communities. The project, which ran between 1977 and 1992, also saw the involvement of photographers such as Sunil Gupta, and visual anthropologists such as Christopher Pinney.24

Considered within a broader temporal arc, one may also view Chhachhi’s Seven Lives as drawing upon a wide range of pre- and post-Independence movements and traditions within and outside the region. These include the Civil Disobedience Movement in India that witnessed an exponential rise in women’s participation in the late 1930s and 1940s; the international Worker’s Photography Movement of the same period; or, returning to India, the pre-Independence bazaar tradition of studio photography, which presented an ‘urban folk’ counterpoint to colonial studio imagery through the rise of vernacular or locally derived formats.25 These struck Chhachhi as vital ‘alternative’ visual cultures and vocabularies following her fieldwork in the 1980s and 1990s in Bengal, as well as in the Hindi-speaking belt of Madhya Pradesh, Bihar and Rajasthan.26

Fig.4

Sheba Chhachhi

Installation view of Record/Resist 2012 at the 9th Gwangju Biennale, Gwangju, 2012

Photo-video installation, 21 black and white digital archival prints and 17 min video loop

Collection of the artist

© Sheba Chhachhi

How do such radical artistic and social paradigms, as well as Chhachhi’s absorption of the past, emerge in her representations of present-day conflicts and movements that are the result of Indian state intervention, majoritarianism and identity politics? Taken as plausible photographic ‘evidence’, her work presents a kaleidoscope of claims and counterclaims made to reflect upon and oppose state machinery in India, with its mottled history of granting rights and liberties. In her installation Record/Resist, for instance, she combines photographs of collective resistance, leftist pamphlets, images of files photographed in government offices, archival imagery and official documents superimposed with handwritten notes, bringing these together with the portraits from Seven Lives (fig.4). Through this combination, which takes the form of twenty-one black and white photographs and a video, Chhachhi creates a shifting narrative that intermixes the voices of the photographer and sitters with the official voice of the state.

With works like Record/Resist Chhachhi draws upon a wider context that includes the rise of leftist social movements internationally and the development of new (Independence and Partition-era) archives and museums in India, Pakistan and Bangladesh. These museums have placed value on family archives and personal testimony as crucial sources that allow for the recalibration of mainstream Indian histories surrounding war, dispute and civil liberties. This approach regards and presents historical memory as polysemic and multi-linear, rather than something to be read strictly within the normative parameters of the ‘national’; it also makes the space for post-memorial engagement with past events, experiences and traumas through the visual archive.27 The need to rethink national histories was further indicated through the display of Chhachhi’s photo and text installation Cleave/Cleave To 1997 in New Delhi during the fiftieth anniversary of Indian Independence; in it, the image of conjoined twins represents an independent India that is nonetheless always tethered to its subcontinental past.28

Within the extensive genre of activist imagery and iconography, Chhachhi’s photographs evoke fresh templates for understanding how power and interpersonal research can be reanimated through layering, metaphor and technology. From the late 1980s onwards, as India’s economy opened up, many photographers had begun to deploy a combination of low-tech media in order to improvise the image and communicate with global audiences,29 seeking new sites of contemporary culture that focused on under-articulated subaltern realities.30 Hence, Chhachhi’s work moves between video and photography: describing Record/Resist, the artist has remarked that ‘The video is of me going back into the archive, remembering incidents, remembering contradictions, remembering experiences across that period of the movement and my engagement as both activist and photographer.’31 In her work Chhachhi has also created alliances with early experiments in video activism and socio-ethical, educational and awareness-building media forums in India, such as CENDIT (Centre for Development of Instructional Technology), Video SEWA and Mediastorm.32

As journalism has expanded exponentially across the globe in the contemporary age, with social media magnates and corporations feeding much of what individuals are exposed to on the ground via the press, so have the strategies of anthropologists, sociologists, artists and citizens shifted in order to create new formats for viewing and receiving multiple perspectives and questioning the totalising capacity of representation. The latter was exemplified by exhibitions such as Middle Age Spread: Imaging India 1947–2004, which took place at the National Museum in New Delhi in 2004 and included the work of eleven photographers – Chhachhi, R.D. Chopra, S. Paul, Kishor Parekh, Raghu Rai, Ram Rahman, Dayanita Singh, Rajesh Vora, Ketaki Sheth, Swapan Parekh and Henri Cartier-Bresson – in order to ‘visualis[e] the spread of the aging body politic of India’.33 In line with these ground realities, Chhachhi’s strategies of engagement, from her documentary work in the 1980s onwards, have explored broader positions through researched, experimental and poetic outputs, including the redeployment of images from earlier photographic projects in subsequent installations. This was seen in the exhibition Counter-Cannon, Counter-Culture: Alternative Histories of Indian Art, curated by Nancy Adajania in 2019, in which Chhachhi showed five of the staged images and two process-sharing narrative sets from Seven Lives.34 As we have seen, Chhachhi has expanded her message through new aesthetic innovations, addressing rights that can and should be exercised, progressive social mobilisations including the struggles of workers that have existed and grown – and eventually, affirming how such personal images are valid, urgent forms of testimony, evidence and ‘truth’.

Mobilising/decolonising the gaze

Exhibition and collection histories of photography have revealed that images were always changing hands (through private means and public museums) and recasting themselves with new identities in new lands.35 This is also the case with the work of contemporary photographers, such as Chhachhi, Sunil Gupta and Dayanita Singh, who became renowned in the West through exhibition and public collection, and who were then also exhibited by national cultural institutions in India, constituting a kind of recognition in reverse.

Since the 1980s, British arts institutions like Tate and the Victoria and Albert Museum have positioned themselves as representatives of ‘world cultures’, raising questions as to whether such objects belong in those collections and how appropriate it is to display them in the museum. The acquisition by Tate of works like Chhachhi’s Seven Lives brings these questions to the fore once again: what is lost and gained in terms of the urgency and intensity of activist photography when it is interpreted and consumed in the Western museum context?

On reflection, perhaps these acquisitions present new templates for including and ‘emplacing’ resistance in the museum, a process that is initiated by the artist and acted upon by the museum.36 In doing so, they can act as a means of countering the current ethos of toxic identity politics, xenophobic suspicion, and the objectification, penalisation and demonisation of the ‘other’ that is part of global conversation today, with local resonances across India. These museum acquisitions may even help us reflect on emerging socio-political conditions in India in the present, such as government-imposed biometric indexing, the revocation of Article 370 in Kashmir without popular consent (recall here Chhachhi’s collaborative work with fellow activist and writer Sonia Jabbar on women’s voices from the Kashmir valley, When the Gun is Raised, Dialogue Stops 2000), or the controversial, recently approved Citizenship Amendment Act that has tried to define which Indian citizens are ‘legitimate’ inhabitants.37

The modern history of photography in India has been identified by visual anthropologist Christopher Pinney as a movement from the ‘studio to the street’. This was a result of the emergence of photojournalism, the coming of the candid photographer and the proliferation of individual photographic practice through handheld cameras such as Kodak’s Box Brownie in the first part of the twentieth century. According to Pinney, in India this allowed for the increasing vocalisation of personal statements and testimonies, a growing focus on the everyday, and a heightened sensitivity towards questions of identity, gender and race.38 This is seen not only in Chhachhi’s Seven Lives, but also the assorted artworks by her near contemporaries, such as Nilima Sheikh, Navjot Altaf, Nalini Malani, Anita Dube and Sonia Khurana, as well as collaborators across disciplines, like feminist publisher Urvashi Butalia of Zubaan Books, who appears in one of the staged photographs (see Urvashi – Staged Portrait, Gulmohar Park, Delhi 1990, printed 2014).

If we are to read Chhachhi’s Seven Lives in the postcolonial ’south’ today, we need to reconsider the images’ varied deployment and usage as modes of advocacy and critique over broad spans of time. We must also be wary of the limitations of oversimplifying the significance of the objects and individuals within the frame, of reading them at face value, when the images are in fact spaces of cohabitation where process, voice and the photographer-subject relationship all reside. Not only this, but Chhachhi’s images take on new meanings in subsequent works: the regimes of looking, of seeing and being seen, that Chhachhi presents in Seven Lives are re-invoked and further complicated in the photo-video installation Record/Resist mentioned above. The staged images that appear in both works alert us to how the process of ‘making visible’ comes with a certain authority and power. Thus, as philosopher Michel Foucault has suggested, power is ‘not an institution, a structure or a certain force with which certain people are endowed: it is the name given to a complex strategic situation in a given society.’39

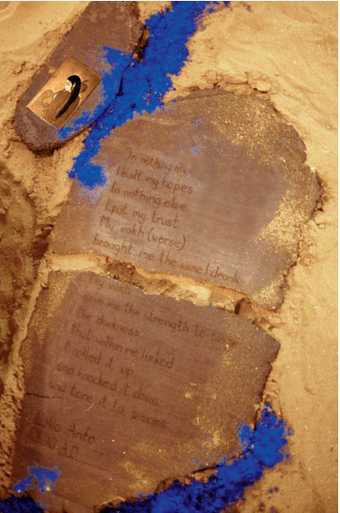

Fig.5

Detail of Wild Mothers I: The Wound is the Eye 1993

3 terracotta sculptures, 9 terracotta tablets, hand-tinted silver gelatin prints, found images, turmeric, pigment and sand

3500 x 2100 x 2500 mm

Collection of the artist

Image courtesy the artist

© Sheba Chhachhi

Chhachhi’s commitment to disenfranchised and subaltern voices is further developed through her interest in the poetic and devotional modes of historical female figures such as Akka Mahadevi (c.1130–1160), Lal Ded (also known as Lalleshwari; 1320–1392) and Karaikkal Ammaiyar (6th century),40 as well as women ascetics today. This enquiry was, in part, influenced by feminist literary research by Susie Tharu, K. Lalita, Kumkum Sangari, and other recuperations of ‘proto-feminist’ history in India.41 Together, such influences created a strong mandate for Chhachhi’s investigation of indigenous forms of countering patriarchy. We see these clearly articulated in her Wild Mothers series, also from the early 1990s, where she not only quotes from the historical figures but also incorporates miniature images of them in her installations (fig.5).

The ongoing resonances of Seven Lives and a Dream

Chhachhi has stated that in Seven Lives, ‘I revisit my archive of documentary images made over twenty years, from 1980 to the early 2000s, to investigate the meanings, slippages and contradictions within collective resistance to explore the construction of subjectivities through social and political processes’.42 As mentioned above, the collection of her work by Tate raises provocative questions about what kind of ‘Indian’ imagery is now being amassed by cultural powers outside India, and what this means for its ongoing reception. What do these photographs mean in the context of such collections today?

We have seen how Chhachhi’s images connect with the global phenomenon of feminist engagement with civil liberties and the need for new treatments of testimony and emancipation. They also help to foster wider discussions around how images can be agents of change. Through exploring ‘theatres of the self’ and meditative moments (in both private and public settings) and presenting these in expansive formats of cultural production, works such as Seven Lives show how photography can be used to heighten awareness of the viewer’s positionality as we witness and bear witness to one another. This also comes through in her 1980s work that took place at the peak of the anti-dowry movement following the Mathura rape case of 1978, and which resonated with the work of her sister, the activist and academic Amrita Chhachhi, and the feminist organisation Stree Sangarsh. It is also seen in works such as the photographic installation When the Gun is Raised, Dialogue Stops 2000; and in Itbari Khan ke Haath, an installation that was first created in 1999 and appeared in a second manifestation at the Dr Bhau Daji Lad Museum, Mumbai in 2012, in which explored the roles and rights of migrant labourers by inserting close-up images of workers’ hands into elite architecture. Chhachhi’s work furthermore focuses attention on ongoing public debates surrounding the freedom to protest in public space, such as at India Gate in Delhi (which has been banned), as well as the draconian death penalty and hunger for retributive justice as exemplified by the Nirbhaya (Jyoti Singh) case from 2012, the same year that Chhachhi made Record/Resist.43

Fig.6

Sheba Chhachhi

Sathyarani – Staged Portrait, Punjabi Bagh Residence, Delhi 1990, printed 2014, from Seven Lives and a Dream 1980–91

Photograph, gelatin silver print on paper

382 x 568 mm

Tate

© Sheba Chhachhi

Fig.7

Sheba Chhachhi

Sathyarani – Anti Dowry Demonstration, Delhi 1980, printed 2014, from Seven Lives and a Dream 1980–91

Photograph, gelatin silver print on paper

386 x 567 mm

Tate

© Sheba Chhachhi

One of the key elements animating Seven Lives is the frequent inclusion of a photograph within the photograph of each participant, inviting the modes of storytelling and intimacy and foreshadowing the exploration of fable that came to play a pivotal role in her later works around ecology.44 This can be seen, for instance, in the staged portrait of Sathyarani (fig.6), which features a framed image of her daughter – the same framed image that Sathyarani carried on the marches protesting the anti-dowry killings that had led to her daughter’s death (fig.7). The complex practice of staging these photographs has been described by the artist as follows:

The process of developing these ‘theatres of the self’ is complex and long-drawn-out, taking shape through intense, intimate interaction over several months, with many revisions and retakes. Both subject and photographer are altered, the conversation of independent individuals made possible by a mutual becoming. We create an inter-subjective field: a space of shared subjectivities that is neither hers nor mine but comes into being between us, mutually constitutive and unique to that moment and that process.45

By addressing notions of domesticity and the inhabitation of public spaces, Seven Lives opens up established tropes of social documentary by claiming the interstitial area that exists between inner and outer lives. It demonstrates and promotes the accessibility of ‘citizens’ who have decided to take on the state, and also broadens the scope of the photograph as a diary entry through which autobiography can be gradually disclosed. Apart from being a veritable record, or a trace, the photograph here becomes a personal memoir for both the author and subject that is produced through open communication between the two.

The enclosed space of a home, as well as the commonplace locations of the street or a bus, suggest environments of accessibility and consent, closeness and alienation that can be experienced via the photographer’s mapping of her subject and their cause. Through picturing such environments, and through her novel approaches to installation design, Chhachhi’s images offer indexical links to a world mediated by interactivity and thus invite a re-examination of the narrative construction of an image in relation to social dominance and tension across class lines. Hence, Seven Lives consolidates and coalesces the sitters’ experiences, helping the viewer to reassess visual expectations, invert markers of stereotype and thereby question the notion of a stable or authentic discourse.

At the same time, we are left with questions: does Seven Lives push us to reassess the much-debated edicts around entrenched journalism and affect that are being re-generated in the present? Is there a need to do so given that the ethos of the traditional ‘image of activism’ mostly does not archive its histories in a way so as to afford them their own lineage? Is the image of the protest or of ‘resistance’ as a field too young, or have we lost too much already over the years through censorship, thereby demanding fresh formats in order to construct a new history?

We might ask further whether it is enough to acknowledge the positions from which Chhachhi’s subjects are speaking. Are these images in fact representative of the women’s movement as a whole, and are they meant to be? Do regional realities reflect other movements and embody the ethics of broader gender-driven forms of resistance growing globally, or does each local reality require a modified approach depending on homegrown particularities? In the artist’s own words, ‘Each woman is different. I am different with each woman. The notion of construction itself changes: the work is predicated on relationship.’46 In this respect, the portraits in Seven Lives allow us to theorise the importance of participation, between objects and people as well as among individuals and communities, and to understand how these yield a profound material, social and psychological interdependence that plays out in photographic representation.

In this way, Chhachhi’s images could allow us to revive other histories that were taking root in the 1980s and 1990s. These include the narratives of resistance explored in forums such as the collective SAHMAT, which was founded following the unconscionable murder in 1989 of leftist activist Safdar Hashmi, a founding member of the local cultural wing of the Communist Party. Chhachhi’s archive contains images of the street performances of plays by Jana Natya Manch, such as Aurat, as well as those of Om Swaha, which was devised with the Autonomous Women’s Association as a response to dowry-related bride burning. These emerged from women’s theatre groups that staged street performances and sit-ins associated with the thespian Maya Rao and the director Anuradha Kapoor, and in that very moment also led to the swift mobilisation of the artists’ and writers’ community in Delhi. One such outcome was Artists Alert (1989), a large show that was organised as a formal tribute to Hashmi and served as the keystone for the cohering of a certain mode of activist art in larger Indian cities.47

In the end, we may ask if the images in Seven Lives continually raise the broader unresolved question of how to depict, or how to bridge the subject and the author – bearing in mind the subtexts of authority, subjectivity and belonging. They also provoke reflection on whether our methodologies of encounter and engagement, as well as broader supporting structures of progressive viewing spaces, may still be imbued with conservative perspectives: where certain disparities are (perhaps unconsciously) internalised and normalised, for instance in museum displays, they may unintentionally lead to the stereotyping of ‘resistance’. Perhaps this body of work sheds light, in unique and timely ways, on the perennial ruptures inherent in finding common spaces between subject and viewer, and between cultural institutions, the administration and the public – especially at this critical time, in the midst of a raging pandemic in Delhi, if not the country as a whole – and in doing so speculates on a new future. As Chhachhi herself says of Seven Lives:

A quasi-fictional representational method emerges, which draws on vernacular practices … Multiple selves appear, each woman includes a previous photograph within the set-up, refusing to be contained within the essentialising unique portrait … We are making fictional truths, performing the real.48