Marcel Duchamp

The Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass)

(1915–23, reconstruction by Richard Hamilton 1965–6, lower panel remade 1985)

Tate

© Estate of Richard Hamilton and Succession Marcel Duchamp/ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2023

Remakes

Artists have often returned to old themes and made new versions of other artists’ works.

The Rake's Progress

British painter William Hogarth created some hugely popular artworks that continue to inspire artists nearly 300 years later. His most well-known works were often called ‘modern moral subjects’. These artworks satirised or criticised the manners and morals of the time he lived in.

We know that 18th Century audiences would have recognised elements of Hogarth's work as mocking things deemed as 'foreign'. When thinking of 'old and new' it's important to recognise and combat the uncomfortable histories and attitudes of the past.

Hogarth’s A Rake’s Progress was a series of paintings and prints following the downfall of a young man coming to London. Tom Rakewell wastes his inherited money till he ends up in the debtors’ prison and finally dies alone in Bethlem Hospital (Bedlam). Hogarth showed the seedy side of London life, poking fun at Tom’s behaviour. He chose real world settings for his scenes. He also included real characters that people would have read about in the papers.

Hogarth knew about the art market too. He made his original paintings into engraved prints. He cannily made two versions and sold them at two prices, so more people could afford to own them.

William Hogarth

A Rake’s Progress (plate 3)

(1735)

Tate

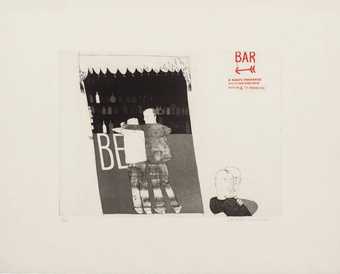

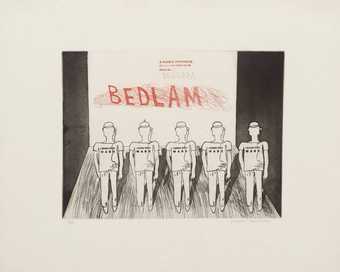

Since then, many artists have used the idea of The Rake’s Progress to comment on society. Yinka Shonibare created a new series called Diary of a Victorian Dandy. It commented on slavery and racial prejudice. Grayson Perry used the figure of Tom Rakewell in The Vanity of Small Differences. He used the figure to explore class differences in the UK of 2012. David Hockney made his version of A Rake’s Progress in 1960-1 based on a visit to New York. Hockney created a character who is consumed by city society. They eventually lose their individuality – becoming just like everyone else.

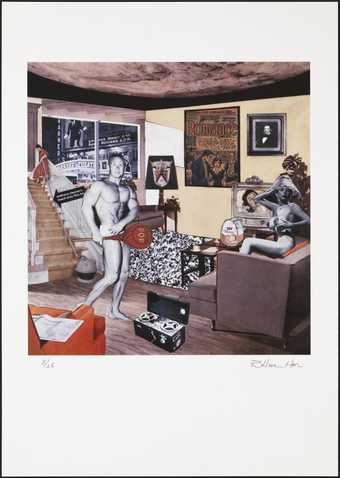

David Hockney

4. The Drinking Scene

(1961–3)

Tate

David Hockney

8. Meeting the Other People

(1961–3)

Tate

David Hockney

8a. Bedlam

(1961–3)

Tate

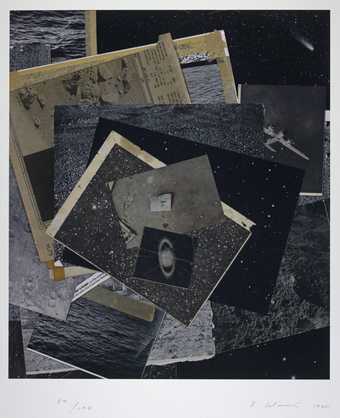

Other remakes

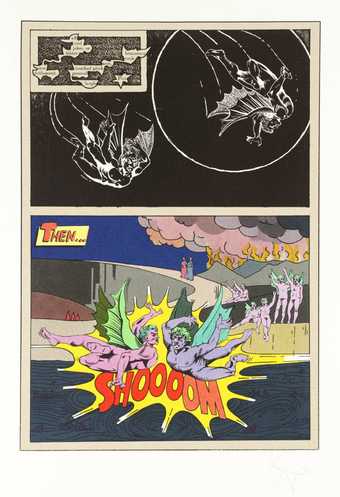

Other old images have also inspired new versions. When Tom Phillips designed a new translation of the Inferno (the first part of the Divine Comedy by Dante Alighieri) he created all new illustrations for it. But in this instance he took an image from William Blake and re-made it in his own style.

Tom Phillips

Canto XXII: [no title]

(1982)

Tate

William Blake

The Baffled Devils Fighting

(1826–7, reprinted 1968)

Tate

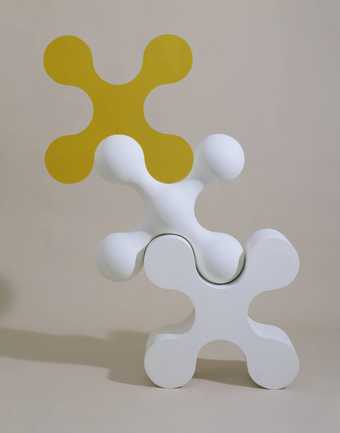

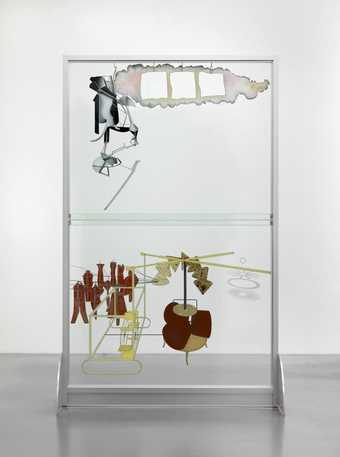

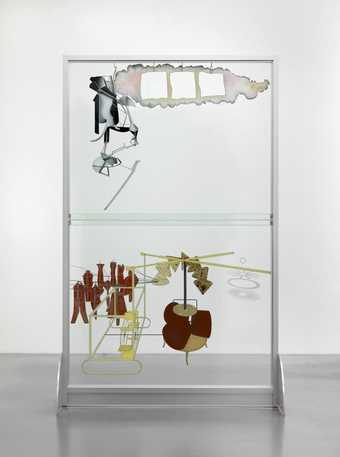

Richard Hamilton painstakingly remade this artwork by Marcel Duchamp. He used the notes and drawings Duchamp had collected to closely follow Duchamp’s original process. When Duchamp visited London, he agreed to sign it ‘as a faithful replica’. This artwork is now credited to Marcel Duchamp. But who made it?

Marcel Duchamp

The Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass)

(1915–23, reconstruction by Richard Hamilton 1965–6, lower panel remade 1985)

Tate

© Estate of Richard Hamilton and Succession Marcel Duchamp/ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2023

Remaking your own work

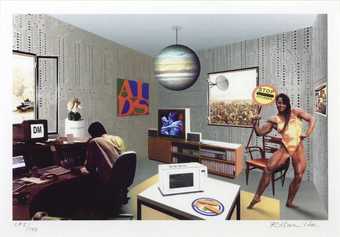

Some artists have returned to a piece of their own work and made a new version. Richard Hamilton made Just what is it that makes today’s homes so different, so appealing? in 1956. The image quickly became one of the most famous images in mid-twentieth-century art. In 1992 Hamilton returned to the image and re-created it as a new version for the 1990s, this time making a digital collage. At the same time he created a new print edition of the original work. This was just as digital printing became accessible. Hamilton created an edition of 25 digital facsimile prints of the work, and then as the technology moved on, in 2004 upgraded the image again.

Rebel against the old – the manifesto

Artists are often among the first to make a social change. Artists can often see themselves as outside society and see art as a way of making change in the world. Many groups of artists have written manifestos to signal how they want to change things.

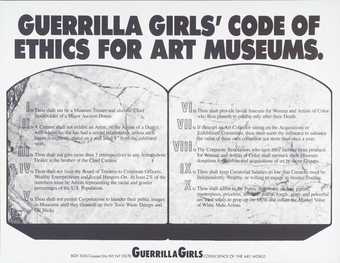

Guerrilla Girls

Guerrilla Girls’ Code Of Ethics For Art Museums

(1990)

Tate

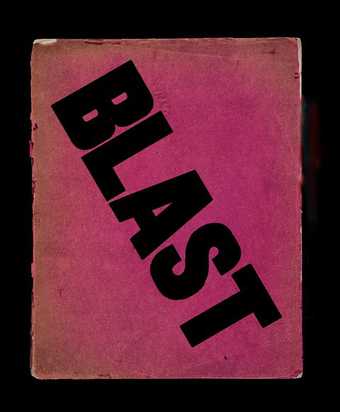

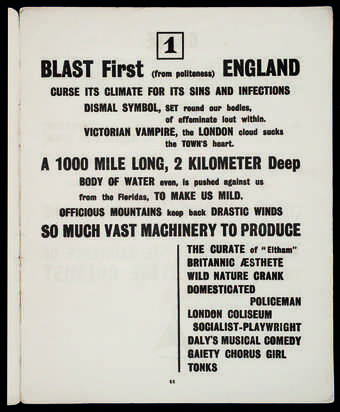

In the early years of the twentieth century, artists across Europe were trying to break away from the old ways of the previous century. In England, a group of artists headed by Wyndham Lewis produced a magazine called BLAST!. It contained a manifesto of things they would ‘blast’ and those they ‘blessed’. They called for art that combined machine-age forms and energetic dynamic forms. They wanted to embrace the modern world and blast away the staid legacy of the past.

Helen Saunders

Vorticist Design

(c.1915)

Tate

Making something new from something old

Marcel Duchamp

Fountain

(1917, replica 1964)

Tate

© Succession Marcel Duchamp/ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2023

Many artworks take something old and familiar and present it to the viewer in a way that gives it a new meaning. The most famous example of this is Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain. Duchamp took a standard urinal from a plumbers merchant and laid it on a plinth, flat on its back. It was signed with one of Duchamp’s pseudonyms, “R. Mutt 1917”. He submitted it for an exhibition in New York. It was rejected, even though all members’ works were supposed to be accepted, and it caused an art world stir. An article of the time (thought to have been written by Duchamp himself), said:

“Whether Mr Mutt with his own hands made the fountain has no importance. He CHOSE it. He took an ordinary article of life, placed it so that its useful significance disappeared under the new title and point of view – created a new thought for that object.”

Duchamp called works like this ‘readymades’. At the time, the readymade was seen as an assault on the status of art but also on the nature of art. Is this art? What can be art? What even is art?

Other artists have taken traditional techniques and used or combined them in new ways to create new meanings.

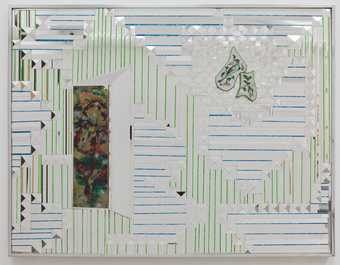

Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian

Something Old Something New

(1974)

Tate

Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian was trained in traditional Iranian techniques of geometric tesselation and and cut-glass mosaic. As she travelled, she also took in European and North American modernist abstraction. She created a practice that combined the two, creating abstract works using traditional techniques.

Grayson Perry creates works using traditional crafts. He’s best known for his pots which are decorated with images and stories that are often drawn from his own experiences. He also creates tapestries and carpets. Vases, pots and carpets don’t usually tell stories, but Perry uses them in new ways to tell his.

Sometimes just a small shift can make something old seem completely new. Elizabeth Wright took her boyfriend’s bike and dismantled it. She photographed each piece and then made enlarged replicas of each part right down to the scuffs, marks and worn tyres. She then pieced the parts back together. The first time it was displayed, she placed it in a corridor, so at first glance it was easy to miss as an art work. Playing with scale can cause a ‘double take’ for a viewer.

Elizabeth Wright

B.S.A. Tour of Britain Racer Enlarged to 135%

(1996–7)

Tate

Old and new: culture and people

Bill Viola is well-known for his huge video projections. In the Nantes Triptych the viewer is confronted with room-height video footage of birth and death.

Bill Viola

Nantes Triptych

(1992)

Tate

Many artists have represented the push and pull between old and new cultures for those who move from one country to another. In Mother Tongue Zineb Sedira shows her mother, herself and her daughter talking to each other about their childhood. Each person speaks in their own native language: Arabic, French and English – and sometimes they do not understand each other. Sedira’s work explores the difficulty of maintaining a shared heritage across national and linguistic divides. Living in a new language or culture sometimes means losing something from the old.

Zineb Sedira

Mother Tongue

(2002)

Tate

Other artists have also made work exploring how it feels to be connected to an old homeland, but also to a new life. There can be struggle to carve and maintain an identity that incorporates both old and new.

Have a go!

Make a manifesto

Vorticist journal Blast No. 1: Review of the Great English Vortex, p. 11, June 20, 1914.

Courtesy The Poetry Collection, State University of New York at Buffalo

© Wyndham Lewis and the estate of Mrs G A Wyndham Lewis by kind permission of the Wyndham Lewis Memorial Trust

It’s just over 100 years since Wyndham Lewis and the Vorticists created their manifesto for a new way of making art. They wanted to break with the previous century. What would you blast or bless from the last century? How would you make things different?

- Write your lists of things to blast and bless. The Vorticists had some fun with their lists, so you can be as specific or broad as you like. They even blasted the sea and the landscape for making the English so mild.

- Research different fonts and try designing your own set of letters to express how your manifesto is new. The Vorticists used big, blocky san serif letters to show that they were different from what had gone before.

- Lay out your lists using your new typeface. Think how you can emphasise important words and phrases using size, placement on the page and capitalisation.