Edward Collier

A Trompe l’Oeil of Newspapers, Letters and Writing Implements on a Wooden Board

(c.1699)

Tate

Edward Collier

Still Life with a Volume of Wither’s ‘Emblemes’

(1696)

Tate

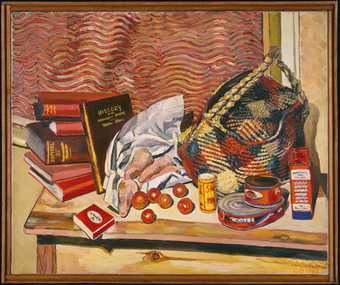

Benjamin Blake

Still Life

(?1829)

Tate

Robert Edge Pine

Still Life with Palette and Brushes, Fruit and Flowers

(c.1760–70)

Tate

Lamia Joreige

Objects of War No.1

(2000)

Tate

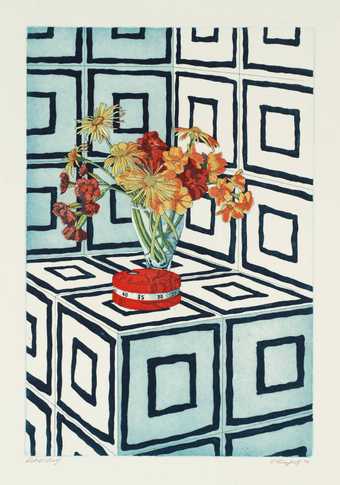

Still life arrangements are still a favourite subject of many artists, especially paintings of fruit, flowers and tableware.

Found Objects and Surprising Compositions

Sometimes taking a familiar object and putting it in a surprising or unexpected position can make us look at it in a new way. Artists can do this simply by placing an everyday item in the gallery space, creating an artwork that influential French artists called a ‘readymade’. Art works like this are now often called found objects.

Haris Epaminonda

Untitled #05 t/c

(2010)

Tate

The Readymade

The most famous readymade is Duchamp’s Fountain. The original artwork was a standard urinal that Duchamp purchased from a sanitary ware supplier and submitted – or arranged for it to be submitted – as an artwork by ‘R. Mutt’ to the newly established Society of Independent Artists in Paris 1917. It was rejected as not being an art work, vulgar and immoral.

A New York art periodical said: ‘Mr Mutt’s fountain is not immoral, that is absurd, no more than a bathtub is immoral. It is a fixture that you see every day in plumbers’ shop windows. Whether Mr Mutt with his own hands made the fountain has no importance. He CHOSE it. He took an ordinary article of life, placed it so that its useful significance disappeared under the new title and point of view – created a new thought for that object.’

It has since become an icon of 20th Century European art, paving the way for many other artists to work with familiar objects and challenge us to look at them with fresh eyes. It makes us think about what the role of an artist is, and what part making plays in art. What do you think? Can an artist choose any object and make it art?

Marcel Duchamp

Fountain

(1917, replica 1964)

Tate

© Succession Marcel Duchamp/ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2023

Assemblage

Putting together collections of found objects to create a new meaning is often called assemblage.

Jimmie Durham’s assemblage of found objects includes the skull and horns of an ibex, a wild mountain goat found in the Alps (he got the skull and horns from a licensed dealer, who only uses materials that arise as a by-product of food production or natural causes, and never from endangered or protected species). The head is fixed to a neck and body of wooden furniture parts: a white lacquered chest, the backrest of a chair and some old table or chair legs. It’s part of a series called Europa, which includes fourteen works dedicated to the largest European animals. It investigates the relationships between humans and animals, especially in contemporary European culture.

“I wanted to gather the skulls of the largest animals of Europe and bring them back into our world by a method which I cannot explain, just as it is impossible to explain most music or poetry. The skulls I worked with all have bodies that are more sculptural than representative. I have the feeling that when using the actual bones, representation of the animal would be too disrespectful to support.”

Jimmie Durham

Alpine Ibex

(2017)

Tate

Found objects don’t have to remain exactly as you found them. For Cornelia Parker’s Thirty Pieces of Silver, she flattened over a thousand silver objects, including plates, spoons, candlesticks, trophies, cigarette cases, teapots and trombones. All the objects were ceremoniously crushed by a steamroller. She has then arranged these flat objects into collections, and suspended them on copper wire hanging about 30cm above the floor. She explained why she used silver objects:

“Silver is commemorative, the objects are landmarks in people’s lives. I wanted to change their meaning, their visibility, their worth, that is why I flattened them, consigning them all to the same fate. As a child I used to crush coins on a railway track – you couldn’t spend the money afterwards but you kept the metal slivers for their own sake, as an imaginative currency and as physical proof of the destructive powers of the world. I find the pieces of silver have much more potential when their meaning as everyday objects has been eroded. ‘Thirty Pieces of Silver’ is about materiality and then about anti-matter.”

Does taking away the use of an object help turn it into art? What properties do you notice about an object like a silver spoon when you can no longer scoop up food with it?

Cornelia Parker CBE RA

Thirty Pieces of Silver

(1988–9)

Tate

Uncanny

Changing the scale of an object can change our relationship to it. It can make it feel ‘uncanny’ which in art tends to mean we find it uncomfortable because it is both familiar and unfamiliar at the same time. It is a term that came from influential psychologist Sigmund Freud who about a hundred years ago wrote an essay called Das Unheimlich - which translated from German means un-homely, or uncanny, but also had another meaning of bringing out hidden secrets from the home. He talked about the repulsion felt around dolls, waxworks, and moving models, the idea of a severed limb having a life of its own, and about ghosts, doppelgangers (meeting someone who is your exact double). While many of his ideas feel outdated today, he had a huge influence on artists of the early twentieth century. The idea of objects in the home or in our body being out of context or having a secret life of their own has been used to horrible effect in many areas of pop culture.

It’s not always horror though, sometimes out of context can feel humorous, or maybe a combination of both, horribly funny?

Salvador Dalí

Lobster Telephone

(1938)

Tate

© Salvador Dali, Gala-Salvador Dali Foundation/DACS, London 2023

Elizabeth Wright

B.S.A. Tour of Britain Racer Enlarged to 135%

(1996–7)

Tate

Cathy De Monchaux

Trolley

(1987)

Tate

Eric Bainbridge

More Blancmange

(1988)

Tate

Advertising & Consumerism

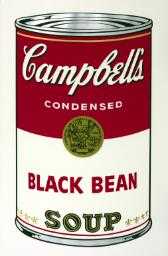

Pop Art of the 1950s and 1960s often responded to or drew upon the crisp clean lines of advertisements or of mass produced packaging.

Andy Warhol

Black Bean

(1968)

Tate

© 2023 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by DACS, London

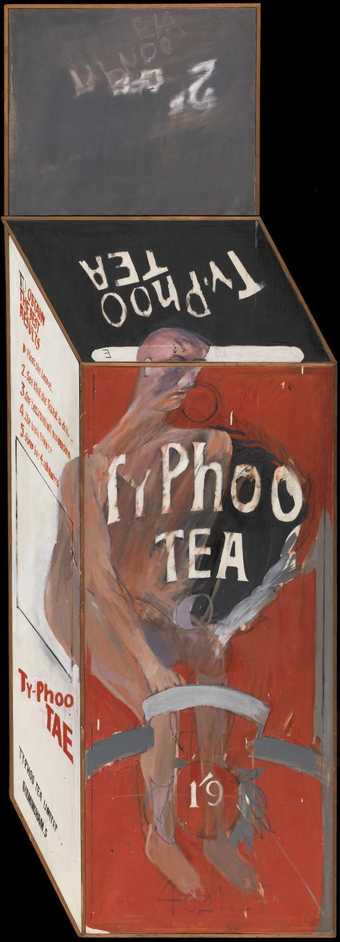

David Hockney

Tea Painting in an Illusionistic Style

(1961)

Tate

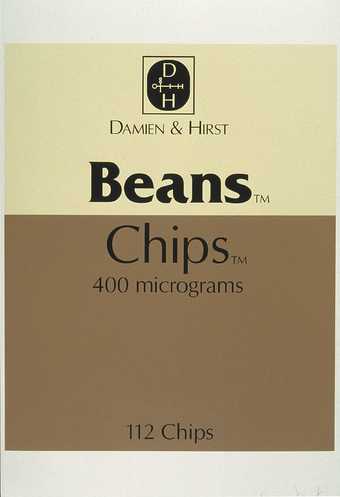

Damien Hirst also uses the conventions of drug and medicine packaging for his print series The Last Supper 1999. The prints look like objects you’d get from the pharmacy, but they all seem to contain foodstuffs you might find in a greasy spoon caff.

Damien Hirst

Beans & Chips

(1999)

Tate

We all own more objects than ever before in human history. Artist Michael Landy is best known for his performance piece installation Break Down (2001), where he set up a factory line in a shop window on London’s Oxford Street and destroyed all his possessions. Landy’s work Scrapheap Services 1995 takes another look at our consumerist capitalist society. He focuses on how corporations and systems can seem to reduce humans to objects, even to rubbish. Landy spent two years raiding tin banks and fast food bin bags for aluminium cans, food wrappers and cigarette packs from which he cut out a simple human figure. Thousands of these are scattered over the floor, spilling out of full litter bins and a street sweepers cart. There are four mannequins dressed in uniforms, who are sweeping up the discarded figures, and all their uniforms display the slogan: 'We leave the scum with no place to hide'.

Michael Landy CBE RA

Scrapheap Services

(1995)

Tate