Introduction

The fifteen net artworks commissioned by Tate between 2000 and 2011 are incredibly varied in both the themes that they explore and the manners of their expression. However, a point of consistency can be found among these works when investigating the background of their commissioning and licensing, as well as their current ambiguous status within the museum.

Although each artwork was commissioned by Tate’s Digital Programmes department, and later by Tate Media, and was licensed for display on Tate’s website, there was variability in how each work was hosted and made accessible to the public. This appears to have been largely determined by the nature of the artwork and the respective technical capacity and resources of both the artist and Tate. The digital infrastructure that supported the artworks was either hosted on a Tate server or remained on the artist’s server, and then accessed via a hyperlink from Tate’s Intermedia Art website. The display of each work was initially licensed for a set period of time (for example, five years in the case of Heath Bunting’s BorderXing Guide 2002–3) and managed through a licensing agreement. However, when reviewing the commissioning and licensing history of the net artworks alongside the extant Intermedia Art website, it is clear that many of the artworks continue to be accessible (to varying degrees of success), despite the expiration of their license agreements. These circumstances pose certain collection management and legal challenges that relate to the ongoing ‘liveness’ of certain artworks, the status that the works hold and Tate’s responsibility and duty of care for preserving them.

Before discussing the status of the net art commissions, it is useful firstly to frame them within the scope of Tate’s collection and the artworks displayed at Tate sites. The net art commissions do not form part of Tate’s art collection as either permanent collection works, for which Tate owns title, or as long-term loans, for which title remains with the owner and Tate has the ability, with the owner’s permission, to display or loan the work. Additionally, although licensed for display, neither are they analogous to the artworks borrowed for short-term exhibitions or displays, which are temporary and always intended to be returned to the owner following the display’s closure. Perhaps the closest comparison can be made with other, primarily tangible artwork commissions that are regularly exhibited at Tate sites; these include Tate Britain’s Duveen commissions or Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall commissions. In these cases, the components of the commission are required to be either returned to the artist or disposed of at the close of the display. These artworks are commissioned solely for display for a set period of time, and by the terms of the agreement would not be retained or maintained by Tate outside of the agreed period, nor acquired for the collection – as was also case with the net artworks. However, it is pertinent to note that the terms of a display commission or licensing agreement do not automatically preclude the later acquisition of works formerly commissioned by Tate, though this would only be possible as a result of a distinct and subsequent acquisitions process.1

The decision-making process for the acquisition of artworks for the collection is a wholly separate process to the commissioning of works for display, and represents Tate’s highest level of institutional governance and due diligence, being representative of the significance of adding artworks to the UK’s national collection of British art and international modern and contemporary art. The multi-stage acquisitions process requires comment from various curatorial and collection care disciplines, the agreement of Tate’s Collection Committee (a group consisting of the museum’s directors and a sub-team of trustees, who are responsible for overseeing Tate’s overarching collecting strategy), before finally being considered and approved by Tate’s Board of Trustees. Acquired artworks are intended to remain permanently as part of the collection and Tate has the responsibility to maintain the long-term condition of each artwork.2 As the net artworks have not been through this process (with the exception of Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industries’s The Art of Sleep 2006 and The Art of Silence 2006), their continued retention and display via the Intermedia Art website, regardless of the degree to which their current display is functional, contribute to an uncertain status and ambiguous position within the institution. Supplementing these circumstances is the recognition within Tate that there is no desire to simply remove the artworks from the website, as they are representative of developments in net art at the time of their commissioning and signify Tate’s only consistent engagement with this form of artistic practice.

The records that Tate holds for the net art commissions are incomplete due to their accidental loss, and as a result it is difficult to determine the exact commissioning process for each work and how the ongoing licence to display was managed. Nevertheless, it is clear that the collection management challenges posed by these works stem from two fundamental factors:

- The works do not form part of the permanent collection and are not owned by Tate.

- The license agreements that were in place to allow their continued display have now expired.

These factors together contribute significantly to the net artworks’ ambiguous status, as well as complicating their intrinsic legal status within the museum. This, in turn, has a powerful influence in determining Tate’s duty of care and level of responsibility in preserving these works, as well as the propriety of their continuing display. The usage of the phrase ‘duty of care’ within this paper refers to the responsibilities a party holds in ensuring an object or artwork receives the appropriate level of care. The appropriate level of care may vary in accordance with multiple factors, including the status of the material, and may specifically relate to documentation, handling, conservation and access, among other practices. Such vernacular is common within collection management and is utilised in both informal dialogue and legal contracts, such as loan agreements and indemnity certificates.3

Conventional statuses of artworks in the collection

As the holder of the UK’s national collection of British art and international modern and contemporary art, Tate’s collection grows steadily each year, usually with the addition of between 500 and 1000 artworks per annum. New acquisitions can enter the collection via several methods – purchase, gift, bequest, allocation by the government in lieu of tax, exchange, transfer and long loans.4 The manner by which an artwork enters the collection has a strong influence on its status within the institution, as well as Tate’s responsibility towards the work and the range of activity that is permitted to be undertaken with it. As was previously alluded to, these distinctions are largely connected to whether Tate holds title to the work.

For artworks that have been accessioned into the permanent collection, Tate holds full title, or, in the case of joint acquisitions, co-owns full title with another institution. It is almost universally anticipated that a permanent collection work will remain as part of the collection in perpetuity, this being in accordance with a core provision within the Museums and Galleries Act 1992 that requires Tate to ‘care for, preserve and add to the works of art and the documents’ in its collections.5 As such, Tate is responsible for ensuring the long-term care of the work. A priority of equal merit can be seen in Tate’s commitment and requirement to ensuring the regular display of collection works through temporary exhibitions and collection displays at Tate sites, as well as around the world through an extensive loans programme.6 Tate balances long-term care with the need to share the collection with audiences in ambitious ways; with its expertise within the field, Tate can identify and adopt whichever approach it deems appropriate to preserve the collection, without, of course, altering the essence of the artwork or violating the artist’s moral rights.

For long-term loans to the collection, title for the work is retained by the lender – the work being lent to enable Tate to display, study or research the work. The loan agreement outlines Tate’s responsibilities towards the work and is agreed for a defined period of time, usually three years (with the option to extend); the work is to be returned to the lender at the end of the loan period (unless its status changes; for example, if it transitions into an acquisition candidate). As the work is not owned by Tate, any display, loan or physical intervention – such as conservation treatment or amendment to the work’s fittings – is only permitted following the receipt of explicit approval from the lender. The level of care that a long loan receives is equivalent to that given to a permanent collection work. However, under certain circumstances, differences in approach can be recognised; for instance, Tate is not obliged to document, photograph or research the work to the same extent. Tate may not necessarily purchase or provide substantial resources for the long-term storage or packing of long loans, like a Tate-designed museum-quality case, for works where the existing packing is suitable in the short term and would be appropriate for the safe return of the artwork to the lender. Similarly, Tate may not pursue discretionary conservation treatment if the condition of the work is not actively deteriorating and is identical to when the work was received at the outset of the loan. Tate’s reasoning for this approach is that any such intervention, if judged nonessential, would not be in the public interest and therefore should not require institutional resource. As a holder of part of the UK’s national collection, and partially supported through public funding, Tate is accountable for ensuring that the taxpayer receives good value for money.7

The perceived importance of holding title, forever

For both permanent collection works and long-term loans, it is clear that ownership of the work lies with either the museum or the lender. The unambiguous nature of who holds title, and the resulting status of the work, represents the circumstances in which museums are most comfortable. As is readily apparent when looking at museum holdings, acquiring full title of objects has been the core method through which museums have developed their collections. Holding title to the work, alongside the ‘permanency’ of collected works, has contributed to the long-standing ideology that the collection is sacrosanct, lying immutable at the heart of the museum.8 Accordingly, acquiring artworks with full title has ostensibly been recognised as the ideal form of acquisition. However, despite the art museum’s ease with this conventional mechanism, certain artworks may only be ‘collectible’ through more diverse forms of acquisition. This may be due to the ephemerality of the artwork or the atypical manner of its creation.

The idealised – but perhaps unrealistic – perception that museum collections should exist in perpetuity, irrespective of their variety and scope, is problematic.9 This understanding, although increasingly less influential in recent years, goes some way towards explaining museums’ traditional resistance to more ephemeral artworks, which, due to their relatively short lifespan, make them less attractive for acquisition and more difficult to allocate institutional resources to.10 Within the art museum, these types of artworks include those that may exist to varying extents, either tangibly or intangibly, or that may exist for limited or indeterminable periods of time.

Fig.1

Joseph Beuys

Fat Battery 1963

Felt, fat, tin, metal and cardboard

132 × 373 × 248 mm

Tate

© DACS, 2021

An example of an artwork of this kind is Joseph Beuys’s Fat Battery 1963 (fig.1). This is a sculpture composed of animal fat, felt and metals within a cardboard box, arranged by Beuys to represent the shape and function of a battery, which reflects his interest in energy generation and storage. The work was initially considered for acquisition by Tate at the June 1974 Board of Trustees meeting, but was formally declined at the recommendation of Tate’s then Director, Norman Reid, due to the ongoing deterioration of the work’s condition, and on the basis that it would be ‘almost impossible to conserve’.11 Reid’s recommendation to decline the purchase of the work went against the strong curatorial rationale for the acquisition as well as the precedent for comparable Beuys works, with similar conservation concerns, being collected by numerous museums throughout Europe.12 Tate’s then Board Chairperson, E.J. (‘Ted’) Power, recognising the importance of the work, purchased Fat Battery himself and offered it to Tate as a long loan,13 eventually gifting it to Tate in 1984. Despite the evident opposing views on the collectability of such an ephemeral artwork, this case is a powerful demonstration of the resistance to artworks that may have finite life cycle. However, Power’s 1974 purchase of the work and its eventual acceptance by Tate as a gift indicates a shift to greater flexibility over time, with the institution eschewing the preference for perpetual and static collections and becoming part of a steadily emerging trend towards a greater appreciation of and commitment to more ephemeral and immaterial products of artistic practice.14

Such examples indicate that museums must develop the mechanisms by which they expand their collections, as these are likely to continue to change and diversify over time, just as artistic practice continues to develop.15 One example of greater collecting diversity is found in the increasing practice of joint acquisition between two or more museums. Although full title of the work is collectively owned by the museums, the development of this manner of collecting signifies a different basis on which museums expand their collections. A further core development can be recognised in the shift from a preoccupation with unique museum objects16 to objects of more varied status, number and diversity, which may commonly contain digital or virtual elements.17 A greater range of the types and statuses of works that Tate holds may have implications for how they are treated within the museum. In a similar fashion to the differences between permanent collection works and long loans, Tate may have different responsibilities towards these works, and have limitations on how they are documented and the activities that can be performed for or with them. Working on the assumption that museums will continue to develop their collections in such ways, it follows that they must become comfortable with more divergent statuses of artworks that may live, perhaps temporarily, within the museum, as well as artworks that may die within it.

The emergence of licensed works

As previously mentioned, museums have primarily developed their collections by adding works to their permanent collections or temporarily holding works on long-term loans. However, Tate has recently pursued a new, additional manner of acquisition through the acceptance of licensed works; at the time of writing in March 2021, Tate holds thirteen licensed works within its collection. The recent development of this collecting status has prompted a moment of reflection and consideration of collection care and collection management themes related to the status of the artworks, Tate’s responsibilities for them, and the principles that guide the approaches taken for their care.

The licensed works that are currently in the collection consist of nine Joan Jonas, two John Baldessari, one Nam June Paik and one Paik and Jud Yalkut artworks that are licensed from Electronic Arts Intermix (EAI), a video distribution charity based in New York.18 EAI holds one of the world’s most comprehensive collections of un-editioned video artworks, which they preserve and share through the lending of works (via temporary media formats) for short-term display, or through the licensing of new un-editioned iterations of the artwork.19

In 2010 Tate’s Board of Trustees approved an Electronic Arts Intermix Video Acquisition Strategy. From 2015, the strategy has been implemented through collaboration between EAI and Tate’s Curatorial, Acquisition Coordination, Time-Based Media Conservation, Collection Management and Intellectual Property teams, and Tate has now developed an ongoing relationship with EAI and routinely acquires batches of works on an annual basis. These works are acquired through licensing with the use of a specialised licensing agreement designated the Archival Purchase License Agreement. By terms of this agreement, Tate receives and retains master-quality media as part of its acquisition of the work and is permitted to produce duplicate media for both archiving purposes and display at Tate sites. The license agreement is open-ended, aiming to represent the life of the artwork, which means that Tate has the right to continue preserving and displaying the work in perpetuity or, of course, as long as the terms of the licensing agreement are observed. These circumstances largely replicate the conditions under which similar time-based media artworks from the permanent collection are cared for and maintained. However, a key clause of the agreement states that Tate is unable to lend the work; instead, it may only be loaned directly from, or with the permission of, EAI. This restriction illustrates a critical departure from permanent collection works, signifying a fundamental divergence in the status of the artwork.

As licensed works, Tate categorically does not hold title to them, despite the fact that the museum receives and retains master-quality media and is responsible for the open-ended long-term care of the retained artwork media. However, at present there is some uncertainty over the degree to which Tate should document and care for these works. The license agreement limits the type and range of activity that the licensee (Tate) is permitted to perform with the work and its media – these conditions immediately signify a divergent status and identify licensed artworks as having a new and distinct collecting status. The development of this distinct status demands that the institution review and interrogate its documentation and duty of care towards these works, which, due to the recentness of the manner of acquisition, have held a somewhat obscure and ambiguous status within the collection. I propose that licensed works could be treated as more akin to long-term loans, such that an analysis of public benefit and the provision of resources must have a determining influence on the agreed institutional approach and the level of responsibility Tate holds for licensed artworks.

Commissioning and documentation

By providing a broad illustration of the different statuses of Tate collection works, I have intended to reveal the particularly ambiguous position the net artworks hold within the institution. In addition to these reflections, it is valuable to consider the commissioning process at Tate and the implications that may arise when commissioned works either change status or are retained for longer than their agreed duration. As previously stated, the net artworks do not form part of Tate’s collection, and therefore have not benefitted from the required level of care and documentation that permanent collection works enjoy. It is important to remember that the net artworks were commissioned and licensed for display only and were not intended for acquisition at the point of commissioning. A key factor that reinforces this point is a convention within Tate that the museum does not commission artworks for acquisition into its collection.20

The net artworks were commissioned by Tate’s Digital Programmes department, and later by Tate Media, and although some were commissioned with input from Tate’s curators, they primarily sat outside of Tate’s standard institutional mechanisms for the commissioning and display of artworks, irrespective of their digital nature. Typically, artwork commissioning is initiated and managed by curatorial teams who coordinate with various collection care departments when, and if, necessary. Due to the incompleteness of the records that Tate holds for the net art commissions it is difficult to ascertain the degree of documentation that was generated for these works at the time of their commissioning and during their licensed display periods. However, it is highly improbable that the level of documentation resembled the obligatory records that are required for coordinating and evidencing the activity of Tate collection works.21

To offer a comparison to other forms of commissioning at Tate it is useful to revisit Tate Britain’s Duveen commissions. In a similar fashion to the net artworks, these installations are commissioned specifically for display, in this case by Tate Britain’s curatorial department. As previously specified, commissioned displays do not require the same type of documentation as collection displays as they do not customarily include Tate collection works; however, this model can become challenging if commissioned works subsequently undergo a change in status, for instance if they become acquisition candidates.

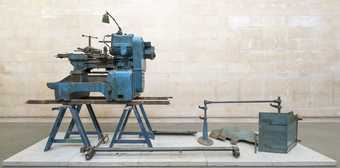

Fig.2

Mike Nelson

The Asset Strippers (Elephant) 2019

Metal lathe, metal trestles, cast concrete tiles, industrial machinery parts and wooden timbers

2705 × 6010 × 1200 mm

Tate

© Mike Nelson, courtesy Matt’s Gallery, London

Photo © Tate

A recent example can be found in Tate’s acquisition of three large-scale sculptures, The Asset Strippers (The Witness), The Asset Strippers (Heygate stack, equivalent for a lost estate) and The Asset Strippers (Elephant) (fig.2), which were originally created as part of a larger installation by artist Mike Nelson for his Duveen commission at Tate Britain in 2019. The documentation requirements for such commissions are less rigorous than those of displays that include Tate collection works, and such documentation may not necessarily demand the use of The Museum System (TMS), the collection management programme used by Tate. In the case of the Nelson commission’s TMS documentation, minimal exhibition, loan and object records were created several months after the opening of the display, and the object records for the three acquired works are not associated with these commission records in any way. As previously noted, the stated level of documentation for the commission is not fundamentally problematic but may become so when artworks originally created for a commission are later acquired. The display of the acquired Nelson works as part of the commission is partially documented through the location histories of the individual works, but inconsistencies between their display dates and status, which should be identical, generates further confusion. As TMS represents Tate’s core tool for documenting display and location histories, a danger exists that the original display history of the artworks may be obscured, fading from readily accessible institutional memory. Tate’s subsequent acquisition of elements of its display commissions, such as these Nelson works, acknowledges their high artistic merit and therefore strengthens the importance of effective documentation practices.

Fig.3

Jan de Cock

Denkmal 53 2005, installed as part of Level 2 Gallery: Jan de Cock, Tate Modern, London, 2005

Another example of a legacy issue – one that bears particular relevance to the net art commissions – can be found with the installations commissioned by Tate Modern’s curatorial department as part of the exhibition Level 2 Gallery: Jan de Cock at Tate Modern (10 September – 30 October 2005). For this exhibition Tate commissioned de Cock to produce multiple large-scale sculptural installations; resembling functional gallery furniture, these acted as aesthetic interventions within various spaces at Tate Modern (fig.3).22 At the close of the exhibition, the installations were meant to be either returned to the artist or disposed of. However, three installations were retained by Tate, either purposefully or inadvertently. For approximately fourteen years, from the close of the exhibition to 2019, these sculptures were situated at Tate Store and were largely forgotten about. The ambiguous status and unintended retention of these objects during this time was partly due to their insufficient documentation, including the absence of TMS object and exhibition records. These circumstances also indirectly led to one of the installations being, for a time, incorrectly associated with the only Jan de Cock artwork within Tate’s collection – Occupying the Museum 2005–12, a work comprising eighty photographs that was acquired by Tate in 2014 and which embodies the only object record associated with the artist on TMS.

The ambiguity of these installations is a concern for multiple parties at Tate but is particularly problematic in collection management terms. Tate’s continued holding of objects with an uncertain status poses questions regarding Tate’s responsibility towards them. Is the museum responsible for maintaining their condition? If so, what collection care activities should be pursued, and for how long? Leading on from questions of responsibility are concerns related to ownership. Does Tate’s retention of the objects fourteen years after the close of the exhibition imply Tate’s ownership, regardless of their lack of association with an accessioned artwork from the collection? If Tate is not the owner then, by standard practice, it should indemnify the owner against the loss of the objects, unless, of course, the owner has explicitly agreed that the materials are lent at the owner’s risk. The number and degree of ‘unknowns’ found in the de Cock example represents a significant legacy issue stemming from the commissioning process: a lack of even fundamental information exists about the works as a result of insufficient documentation and the loss of institutional memory due to the passage of time and the departure of staff who organised the exhibition.

During a 2019–20 collection care storage and movement project that sought to maximise artwork storage across Tate sites, the legacy issues of the de Cock installations were discovered and addressed. The project’s coordinator, Collection Registrar Birgit Dohrendorf, accessed all the available records associated with the commission and, having liaised with curatorial colleagues, re-initiated contact with the artist in late 2019, with the hope of resolving these issues and finally either returning the objects to the artist or disposing of them in an appropriate way. Through these discussions it was agreed with the artist for the objects to be disposed of through their destruction, which was completed in March 2021.

The future of the net art commissions

The concerns highlighted in this essay can be seen to relate substantially to the net art commissions in terms of status, duty of care and the legacy of commissioned works. When reviewing the interviews conducted with the commissioned net artists as part of the project Reshaping the Collectible: When Artworks Live in the Museum, there appears to be a lack of clarity and a wide range of attitudes to the status of the artworks and who owns them – whether the artist or Tate.23 Inextricably linked to this is an ambiguity as to who is responsible for maintaining the care of the artworks, if this is required, and what the future of the works should be. The project team and Tate are seeking to re-engage with and resolve their legal status; this is especially important as Tate hopes to continue to maintain the display of these works.

If the institution intends to continue to hold and display these net artworks with the artists’ agreement, then new license agreements will need to be instituted. EAI’s Archival Purchase License Agreement provides a useful example and partial template for how this could be formulated. A second example can be found in the bespoke license agreement that the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York employs for its net art commissions. This agreement is also open-ended but includes a crucial clause stating that the licensee is only required to maintain and display the artwork for as long as they wish. This provision is particularly useful given that changes in technology – both anticipated and unanticipated – may profoundly affect the institution’s capacity to maintain and display net artworks in the future.

Two of the core outcomes of the Reshaping the Collectible project have undoubtedly been the renewed attention brought to a series of artworks that have remained in a state of limbo for many years, and the research to uncover the legacy of these works. Addressing the net artworks’ invisibility has been a collaborative effort across Tate, including teams from Conservation, Technology, Digital, Collection Management, Curatorial and Research, to re-engage with the works and the traces they have left in the museum. The future of these artworks, as well as the contextual background of their commissioning and licensing, is still being explored, and a variety of approaches may ultimately be employed to do so, with the permission of the artist when necessary. The status of the artworks, or the elements of them that remain, might change as they find a new home in the museum. Updated license agreements that incorporate the insights found within the EAI and Whitney agreements could be employed to continue the works’ display, such as it is; or perhaps the ephemerality of the artworks will be embraced, and it will be accepted that the artworks will fade away and finally vanish as technology and time progress.