Introduction

With the arrival of the browsable web in the early 1990s, a new artistic practice surfaced which, according to curator Christiane Paul, ‘call[ed] for a “museum without walls,” a parallel, distributed, living information space that is open to interferences by artists, audiences, and curators – a space for exchange, collaborative creation and presentation that is transparent and flexible.’1 The resulting artworks are an assemblage of sites, practices and contexts that incorporate, perform and reflect the technologies that were available, the space, shape and feel of the internet at the time, and the social and political conditions in which they were created. Net art, or web-based art, has a ‘chaotic sensitivity to its context’,2 according to artists and theorists Rosemary Lee and Miguel Carvalhais. As such, when we interact with or perform a work now that was created two decades ago, for instance, it is difficult to fully understand the artist’s intentions – that is, without knowing the work’s ‘site-specificity’3 and without access to some of these contexts, two of which are the internet and the World Wide Web.4 Although net art has had many phases, it initially grew out of and was ‘nurtured within a supportive community of practitioners’ who were working together, often sharing an internet server and gathering frequently online and at international events to discuss ideas.5 As a practice net art offered an alternative to large cultural infrastructures, and for many it was anti-institutional. When we look at this practice now through the lens of the museum – in this case, Tate – and through art history, as I do here as part of the project Reshaping the Collectible: When Artworks Live in the Museum, net art’s live and evolving contexts, its creation and circulation online, the way it performs on screen and the importance of collaboration in its production and dispersal present challenges to the inherited structures and practices of museum curating and collecting. They challenge the museum’s methodologies of historicisation, which have been designed not around collectively created and ever-changing artworks, but around singular, static objects and histories.6

This essay explores the history of the fifteen net artworks commissioned by Tate for its website between 2000 and 2011, in order to understand if and how the museum might help audiences to encounter these works and their contexts today. The commissioning series began at a significant moment for Tate: it took place during the year that Tate Modern first opened, Tate Britain was being redeveloped, the museum’s website was relaunched and Tate underwent an institutional rebrand. If we place the net art commissions in technological history, the period of time in which they were created saw the shift from Web 1.0, characterised by static html pages, to the dynamic, participative, information-sharing and user-generated content of Web 2.0, which took place around 2002.7 In addition to moments of technological change, many of the net art commissions can be understood in relation to shifts in the way global politics were operating online prior to and during this time. Many of the artists involved in Tate’s commissions, for example, have spoken about responding to the increased online surveillance that followed the terrorist attack on the World Trade Centre in New York on 11 September 2001.

These fifteen commissioned net artworks and their histories are persistent. They have been written about as individual works and as a series of commissions in studies on digital art practice, curatorial practice and histories of new media.8 They have been reflected on at conferences and events and are also the focus of one of the Reshaping the Collectible case studies.9 Yet despite the various ways in which they have been examined and reflected upon, knowledge of the commissions remains largely absent from institutional memory at Tate. This is true of the commissions as well as the practice of net art: 2020 marks the year in which the first net artworks will come into Tate’s collection, and these first acquisitions also happen to be two of the fifteen net artworks commissioned by Tate. The Art of Sleep and The Art of Silence by Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industries were created for the Tate net art series in 2006 and will finally enter the collection fourteen years after they were made and three decades since the first webpage went live on the open internet. Another work in the collection with a website component is Yinka Shonibare’s The British Library 2014, acquired in 2019.10

In addition to the absence of net art in Tate’s collection until 2020, our research into the net art commissions as part of Reshaping the Collectible reveals that the records for the commissions are missing. Elsewhere in this publication Sarah Haylett, Archivist and Records Manager on the research project, considers what led to the loss of these records and explains how she has gone about reconstituting the records.11 My reason for mentioning it here is to suggest that part of the reason for this loss, as well as the lack of net artworks in the collection, could be the hierarchies of knowledge that exist in the museum. The net art series was curated not by the Curatorial department but by a succession of individuals, first in National and International Programmes, then in Digital Programmes from 2001 (a new department within National and International Programmes), then in the Tate Media team from 2007. At a relative distance from Curatorial, the series was arguably seen as a form of marketing and an educational project rather than a part of the museum’s artistic programming. As Emily Pringle, Head of Research at Tate, articulates, the museum is still dominated by the historic notion of the scholar curator.12 An effect of this is that other knowledge-producing practices in the museum, such as learning, digital and conservation, can slip into the gaps between the museum’s visible platforms, and as such become occluded both inside and outside the museum.13 In this essay I address how the periodic institutional invisibility of net art and its histories is an example of a museological blockage surrounding net art as a practice.

In art history and curatorial practice, some have connected net art to political and social activism, to post-internet art and to the legacies of conceptual art, Fluxus and ‘intermedia arts’ (a term referring to multimedia practices originating in the 1960s and 1970s). Histories of net art within and beyond the discipline of art history include those by Tilman Baumgärtel (1999),14 Josephine Berry (2001),15 Vuk Ćosić (2001),16 Sarah Cook (2000–1),17 Sarah Cook and Beryl Graham (2002),18 Julian Stallabrass (2003),19 Rachel Greene (2004),20 Mark Tribe and Reena Jana (2006),21 Edward Shanken (2009),22 Christiane Paul (2008–16)23 and Josephine Bosma (2011),24 as well as media arts organisation Rhizome’s Art Happens Here: Net Art Anthology (2019).25 On the whole they all cover a similar time period, from the early 1990s up until the moment of each text’s writing. They also cover similar narratives of origin, artists and networks. They all reiterate the significance of net art’s social, technological, political, personal and aesthetic contexts in understanding, communicating and accessing net art and its histories. However, there are contradictions across these accounts. As well as variations in terminology (net art, internet art, web-based art) and some differences in locating a point of origin, there is debate about whether or not to characterise net art as an artistic practice in its own right or whether to place it within a longer artistic tradition. Bosma, for example, sees the ‘annexation and embedding of net art within older terminologies (digital art, media)’ as a reaction to the negative responses in art criticism to new media art and instead emphasises the importance of the network, since it is this that ‘implies a flow and positioning, variety and collectivity. It allows for divergences that remain interconnected.’26 While Berry, Paul and others share Bosma’s views on the importance of the network, they see a benefit in placing net art within a longer art historical trajectory, such as digital arts practice, or in relation to movements like conceptual art.

As well as the selected ‘published’ accounts mentioned above, a large majority of net art histories can be found online on webpages (live or archived) and in mailing lists established for artistic and curatorial practice (such as Nettime (1995), Syndicate (1996), New-Media-Curating (2000), Xchange (1997) and Undercurrents (2002)).27 In a layering of historical reflection, the authors mentioned above have set up and contributed to these mailing lists and draw on these discussions in their published accounts. What I have found in accessing this material is that as archival sources they make the history of net art on the one hand highly accessible – anyone with internet access can search and find primary source material through posts and discussions – while on the other hand they are also precarious. If the sites containing this contextual and historic material are not maintained, financially supported or archived, then there is the continual threat that pages like these will continue to disappear. With this comes the potential for loss of knowledge around net art’s practices, its context and its networks.28

The precarity of net art and its contexts has been and is being addressed by organisations and individuals who are invested in these histories. In her practice as a writer and curator Christiane Paul has worked hard to make net art visible and ensure that it is historicised as a digital arts practice.29 Sharing Paul’s commitment is Rhizome, which in 2019 launched the aforementioned Net Art Anthology, an exhibition and printed and online catalogue that aimed to preserve and make available over one hundred works of net art created between 1982 and 2016.30 All of the archived works are also available online where they can be explored along with archival material, photographs, reviews and artist quotations. According to Rhizome’s Artistic Director, Michael Connor, the anthology ‘prioritiz[ed] works that gave form to important critical positions throughout the development of the net: some that flourished in their time, but lack contemporary descendants; and others that anticipated later developments in net art with almost uncanny precision but have been largely forgotten.’31 Connor describes these works not as objects but as things that can be set ‘in motion’, not only once, but periodically in the future.32 Projects like these and preservation initiatives such as Webrecorder and Emulation as a Service are driven by a commitment to the legacy of net art: the ideas, individuals, collectives and (often open-source) technologies through which net artworks are created, circulated and preserved.33 They are also motivated by a desire to safeguard these works for the future as more and more early webpages disappear.

In this paper I consider the challenges that surround net art’s collection and historicisation by museums through the example of Tate’s commissions. I address net art’s fluctuating visibility and invisibility both inside and outside of the institution. I explore the institutional and political conditions that made the commissions possible, relating this to access and inclusion agendas in politics, culture and education in the UK in the late 1990s. I compare Tate’s commissions and curatorial approach to other, similar initiatives by large-scale museums, exploring the infrastructures and networks that existed for net art in its early stages and the ways net art moved into large organisations. Throughout, I acknowledge and build on the huge amount of work and research already undertaken by individuals in this area. The essay concludes with my reflections on how, given the challenges that come with net art, museums like Tate might help keep net artworks and their contexts alive.

The first net art at Tate

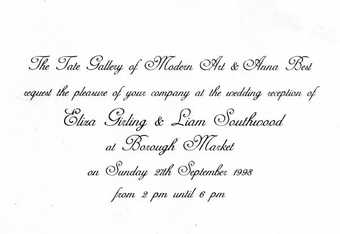

Fig.1

Anna Best

Wedding Project 1998

© Anna Best

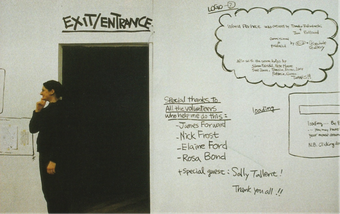

Fig.2

Anna Best

Wedding Project 1998

© Anna Best

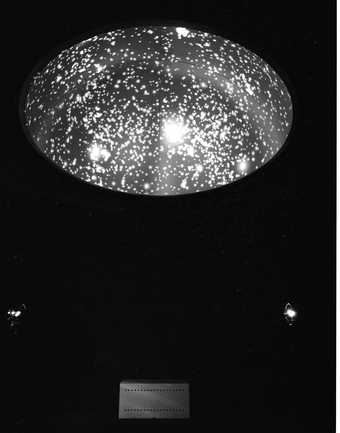

Fig.3

Karen Guthrie and Nina Pope

Broadcast (29 Pilgrims, 29 Tales) 1999

© Karen Guthrie and Nina Pope

Photo: Jet

The pre-opening programme for Tate Modern that took place in 1998–9 created an institutional context out of which the net art commissions surfaced. This programme included an invitation for artists to work in Bankside Power Station before it opened up as the new Tate Modern, and a series of artist commissions in nearby Borough Market.34 Like the net art commissions, many of the works produced as part of these initiatives were examples of socially engaged, participatory forms of public art. For Tate, these projects were a way of connecting and including audiences (locally for the pre-opening programme, and nationally and internationally for net art) and helping the institution feel more accessible. Like the net art commissions, which were led by Tate’s Digital Programmes department, they were curated in the interstices within the institution’s curatorial programme and before the formalised exhibitions and collection displays at Tate Modern took shape. One of the works commissioned was Anna Best’s Wedding Project 1998 (figs.1 and 2), a real wedding performed in Borough Market and filmed for TV. Responding to a brief that was set by Tate to involve Tate staff and ‘local’ people, Best created a performance that acknowledged the undercurrent of gentrification in the area at the time – of which Tate Modern itself was an example – by playing on Tate’s attempt ‘to marry a “new audience”’.35 Broadcast (29 Pilgrims, 29 Tales) by Karen Guthrie and Nina Pope followed in 1999 (fig.3). Building on the presence of Borough Market in Geoffrey Chaucer’s literary work The Canterbury Tales (c.1400), Guthrie and Pope invited twenty-nine people to perform a contemporary pilgrimage of their choice. Their individual tales were broadcast from the Tabard Inn on 11 September 1999 to a live audience present in the nearby market, as well as to an audience online.36

Both of these performances were socially engaged and site-specific. The artists brought forms and practices of technological mediation (video, television and online) together with shifting ideas of public art and concerns about the effects of gentrification. For Tate, these projects, like net art, can be understood as part of a strategy to address concerns held by Tate about the organisation’s expansion both locally and nationally. They are significant to the history of Tate and yet references to these performance commissions, either from this moment in Tate’s development or in relation to the net art commissions, are hard to locate. Although some of the press releases can be found on Tate’s website,37 this is not comprehensive or consistent. They are also not archived on the Intermedia Art site – a microsite within Tate’s website where the net art commissions were hosted from 2008. Responding to the feeling of occlusion a few years after they created the works, Guthrie and Pope commented: ‘On the website for the Tate there is still no link that I can find to our project. And it is just tiny things like that that help the legacy of the work that you’ve put into a one-off, live or new media event go on.’38 As temporary projects they easily fall into a gap of institutional invisibility, as has also been the case with net art. Acknowledging them here shows the connection between socially engaged, public and performance art and the history of net art, and highlights the complex relationship between artists, audiences and the institution with regard to such artworks’ visibility and longevity.

A formalised programme of net art subsequently took shape at Tate from 2000 with a total of fifteen works launched online. These are Graham Harwood’s Uncomfortable Proximity 2000, Simon Patterson’s Le Match des Couleurs 2000, Heath Bunting’s BorderXing Guide 2002–3, Susan Collins’s Tate in Space 2002–3, Natalie Bookchin and Jacqueline Stevens’s agoraXchange 2003, Shilpa Gupta’s Blessed-Bandwidth.net 2003, Andy Deck’s Screening Circle 2006, Marc Lafia and Fang-Yu Lin’s The Battle of Algiers 2006, Golan Levin with Kamal Nigam and Jonathan Feinberg’s The Dumpster 2006, Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industries’s The Art of Sleep 2006 and The Art of Silence 2006, Qubo Gas’s Watercouleur Park 2007, Bunting’s A Terrorist – The Status Project 2008, Marek Walczak and Martin Wattenberg’s Noplace 2008 and Achim Wollscheid’s Nonrepetitive 2011.39 The first commissions went online in 2000, when the Tate website (which had first been launched in 1998) was redesigned by Nykris Digital Design, with sponsorship from BT.

The first two net artworks – Harwood’s Uncomfortable Proximity (launched on 26 June 2000) and Patterson’s Le Match des Couleurs (launched on 12 July 2000) – could be found by clicking on ‘Tate Connections’ on the homepage and then ‘Art Projects Online’. From 2002 a button for ‘Net Art’ appeared on the homepage, leading to a page dedicated to the net art commissions as and when they were added to the site. The artworks sat on this page alongside a description of the work, an artist biography and a commissioned essay.40 In 2008 they were relocated onto Intermedia Art, a microsite within Tate’s website, where they were brought together with performance and film-based programming at Tate and other forms of discursive activity, such as email discussions. As part of a redesign of Tate’s website in 2012, the Intermedia Art pages that contained the net art commissions were migrated from the main site and server and placed on a sub-directory on a second server, ww2.tate.org.uk/intermediaart. Part of the reason for the gradual removal of the net art pages is arguably that they were curated from 2001 by Digital Programmes and then by Tate Media (an earlier iteration of what is now the Digital department), rather than by the Curatorial teams, and as such sit lower down in the hierarchy of knowledge in the museum. This is something I explore later in this essay. However, before going into detail about these works and the curatorial approach, it is important to consider why Tate was entering the pre-existing net art scene.

Net art’s rise in the 1990s

By the time Tate began to commission artworks for the website, ‘net.art’41 had already been declared dead.42 As curators Sarah Cook and Aneta Krzemien Barkley describe, from the mid-1990s ‘grass‐roots, ad‐hoc, and temporary “autonomous zones,” meet‐ups, get‐togethers, and file exchange initiatives’ flourished as spaces where artists, technologists, software engineers, curators, writers and collectives could produce, support and circulate net art.43 Alongside these grassroots initiatives were festivals, educational organisations, collectives and art spaces.44 Net art was as such international but rooted in local networks and infrastructures. Some were located in Eastern Europe (supported by investor and philanthropist George Soros),45 North American cities (New York and Los Angeles), European cities (London, Berlin, Paris and Amsterdam) and in Eastern Australia, where curatorial programming and networks associated with net art were supported by the Australian Network for Art and Technology, founded in Adelaide in 1994.46 These locations, as well as others, were important for the curation and dissemination of net art. Many organisations, like Rhizome (based in New York), started out as listservs (electronic mailing list communications that have been archived online) or email discussion lists. In 1991 Wolfgang Stahle founded The Thing, an art bulletin board initially based in New York and then with nodes in different cities: in each location it ‘fostered a community of practitioners who engaged in experiments with political organizing, writing, performance, and the sale and distribution of artwork online.’47 In 1995, Benjamin Weil, who had been involved in The Thing in New York, worked with John Borthwick, a new media developer in Manhattan’s Silicon Alley, to set up the website äda’web (1995–8), headquartered in New York and now in the collection of the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis. This platform provided opportunities, space and support for established artists – mostly those without technical skills – to explore making work online.48

In the UK, Heath Bunting founded the collective and website irational.org in 199649 and set up and ran radio transmissions and listening and internet stations internationally, such as cybercafe @ kings x in London.50 Furtherfield, an arts community founded by Marc Garrett and Ruth Catlow in 1996, provided opportunities and spaces for net artists and activists, both online and offline. The same year, Gary Stewart became Digital Curator at Iniva (the Institute of International Visual Art) in London, commissioning work for Iniva’s website through X-Space, a virtual gallery for work by young artists from diverse cultural backgrounds.51 Backspace (bak.spc.org), founded in London in 1996 by James Stevens, provided artists with an internet connection and training if needed, so that artists like Guthrie and Pope, who used Backspace for Broadcast (29 Pilgrims, 29 Tales), could make work online and ‘experiment with audio and video live streaming over the internet’.52 Low-fi was a UK-based artist collective that was set up to commission net art and provide exposure for other net art projects, and included contributions from guest artists and curators.53 Pedagogical environments run by collectives were another important infrastructure in the shaping of net art. For example, Artec (London Arts Technology Centre) was established in 1990 under the European Commission’s London Initiative. It provided training in digital technologies for the long-term unemployed and served as a meeting place for artists.54

Fig.4

IBM computer terminals showing the net art exhibition at Documenta X, Documenta-Halle, Kassel, 1997

Photo: Joachim Blank

In the late 1990s, large-scale art galleries and museums began to get involved with net art, either by bringing it into gallery exhibitions or by commissioning works for their websites.55 However, since many of the works had been launched independently of institutions and ‘without the obvious need for the curatorial framing that a museum or gallery provides in order to engage their publics’, as Cook and Barkley observe, they encountered numerous issues in their recontextualisation.56 One example is the 1997 iteration of the contemporary art festival Documenta in the German city of Kassel. Directed by Catherine David, it included a display of net art curated by Simon Lamuniere (fig.4). These net artworks were hosted on the Documenta website and visitors were invited to experience them by accessing the website at IBM portals located in a space designed to mirror an office environment. The display was criticised by some in the net art scene due to the fact that it was located behind the cafeteria and thus isolated from the rest of the exhibition, and because – with a few exceptions – the computers were not connected to the internet.57 These concerns about the physical marginalisation of net art in the gallery space echo the frustration with film and video exhibitions from the 1970s.58 As was often the case when presenting net art in contemporary exhibitions, the artists were not consulted on how their work should be displayed. To add insult to injury, when the exhibition closed the organisers of Documenta announced their plan to take the website down and to sell the net art commissions on a CD-ROM. Vuk Ćosić responded by hacking the Documenta X website, copying the contents onto his own server (Ljudmila.org) and titling it Documenta Done. One successful part of Documenta, however, was the discursive programme ‘Hybrid Workspace’, which included a series of residencies, interviews and group discussions programmed in collaboration with the Berlin Biennale.59 While the recontextualisation of net art into the white cube gallery space proved problematic, ‘Hybrid Workspace’ was more reflective of the networked and collaborative nature of net art, as curator and writer Lisa Haskel has suggested.60

Fig.5

Installation view of Marek Walczak and Martin Wattenberg’s Apartment 2001 in the exhibition Data Dynamics, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, 2001

Other large-scale institutions included net art at the same time and encountered similar criticisms.61 One curator who took the approach of locating net art within a legacy of conceptualism and digital arts, often showing net artworks as gallery installations, was Christiane Paul. In 2001, following criticisms of the net art component of the 2000 Whitney Biennial, Paul curated Data Dynamics at the same museum (fig.5). The exhibition ‘consisted of five projects of net art (and networked art), all shown as installations or projections.’62 According to Paul, this approach ‘was driven not by a desire to make it “easier” for the visitor’, but was more about responding curatorially to ‘the explicit comment’ within all the works ‘on notions of (physical) space’.63

Fig.6

Installation view of Tomoko Takahashi and Jon Pollard, Word Perhect at Chisenhale Gallery, London, 2000

Fig.7

Installation view of Lise Autogena and Joshua Portway, Black Shoals Stock Market Planetarium 2001 in the exhibition Art Now: Art and Money Online, Tate Britain, London, 2001

Photo: Tate

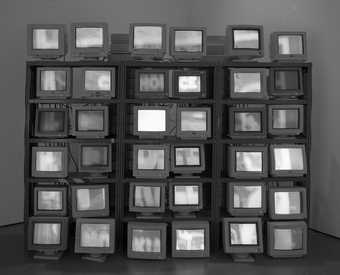

Fig.8

Installation view of Redundant Technology Initiative, Free Agent 2000–1 in the exhibition Art Now: Art and Money Online, Tate Britain, London, 2001

Photo: Tate

In a comparatively minor way, net art had also been surfacing in exhibitions at Tate around this time. In 2000, Tomoko Takahashi and Jon Pollard’s internet project Word Perhect (commissioned by digital arts organisation e-2 and the Chisenhale Gallery, London; fig.6) was the first net artwork to be nominated for the Turner Prize.64 This was a hand-drawn word processing programme which visitors could play with in the gallery and online. The following year, curator and art historian Julian Stallabrass’s exhibition Art Now: Art and Money Online was held at Tate Britain, exploring the commercialisation of the internet. This included three installations: Black Shoals Stock Market Planetarium 2001 by Lise Autogena and Joshua Portway, in which audiences were ‘immersed in a world of real-time stock market activity, represented as the night sky, full of stars that glow as trading takes place on particular stocks’ (fig.7);65 Free Agent 2000–1 by Redundant Technology Initiative, an installation of computer monitors displaying material from websites offering people free goods (fig.8); and Jon Thomson and Alison Craighead’s CNN Interactive Just Got More Interactive 2001, where visitors could ‘select emotive, if tawdry, soundtracks to accompany the news of the day on the CNN website’.66 At the same moment Shilpa Gupta’s net artwork Sentiment Express 2001 went on display in Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall as part of the exhibition Century City (1 February – 29 April 2001). It was displayed as a booth within which people could sit at a computer and either dictate their own sentimental letter into a microphone or select a pre-existing one; this would then be handwritten, scented and posted to the recipient by a team of workers in Mumbai.

Alongside these exhibitions there was an interest at the time in the potential of the virtual museum, and large-scale museums and galleries like Tate began to extend their gallery spaces online by commissioning art for their websites. This meant that on the museum’s website, along with basic visitor information, access to digitised collections, events information and a history of the organisation, visitors might enter, view and participate in a virtual artwork. Examples of this kind of online programming include Tate’s ‘Net Art’ pages (2002) on what was described as ‘Tate’s fifth gallery’;67 SFMOMA’s ‘E.space’ (2002); the Walker Art Center’s ‘Gallery 9’ (1997–2003), conceived by curator Steve Dietz as an extension of the gallery into the virtual environment; Dia Art Foundation’s ‘Web Projects’, launched in 1995 and curated by Lynne Cooke and Sarah Tucker; and the Whitney Museum’s ‘Artport’, which was created and curated by Christiane Paul from 2001 and included resources, net art exhibitions and net art commissions.68 Writing an analysis of these various examples, curator Marialaura Ghidini argues that these institutional online exhibitions adapted earlier models set by Rhizome’s ArtBase and the online gallery äda’web, but differed in the level and positioning of mediation. Of Dia Art Foundation’s Web Projects, Ghidini writes:

Due to the fact that artworks were only accompanied by an introductory text, a biography of the artist and a concept description highlighted how the DIA Web Projects series was based on an understanding of the website as an exhibition space where the curator regained the role of the mediator. Cooke and Tucker, beyond taking care of the commission process, mediated the art experience of the viewer. They created a conceptual framework for contextualising each artwork and the artist’s practice, rather than just mediating the viewer’s experience with the interface.69

The curated environment of the Dia Web Projects is contrasted with the experience with äda’web wherein the visitor would view a work ‘as part of a complex hyperlinked environment that emphasised the architecture of the website’.70 In Ghidini’s view, the curating of the Dia Web Projects brought models to the website that were designed for the gallery and museum, rather than responding to the context of the website as an ‘ecosystem that is socio-cultural, political and economic’.71 This criticism could equally be levelled at Tate’s net art commissions, which, as we will see, followed a similar approach: works were interpreted for audiences through information about the artwork, the artist and via a commissioned essay. Although some of the commissions embraced the hyperlinked environment (Harwood’s Uncomfortable Proximity, for instance), structural limitations within the organisation filtered down into the architecture of the website, resulting in works being contained and interpreted rather than cross-pollinating among Tate’s programming or beyond its website. An additional problem, pointed out by Christiane Paul, was the way museums followed the trend of net art without the technological and conceptual infrastructure to support it.72

The internet had freed artists from being reliant on large-scale organisations and their associated structures or the priorities of their funders. But when opportunities arose for artists to show their work with major galleries through exhibitions or their online servers, the discoverability that this enabled brought the potential for artists to reach new audiences beyond their existing net art ecosystems. Via an institution like Tate or the Whitney they could collaborate with and critique the institution, fictionalise it, or set up within it environments for debate and exchange. From the museum’s perspective these online artworks and online galleries were part of a shift in audience development that occurred in the late 1990s. Taking the example of Tate, the moment of commissioning the net artworks coincided with two major shifts: new technological capabilities and a change in government. The next section will show how in the UK, the technological, creative and social visions of the internet from the artists’ perspective found common ground with cultural programming and government policy for reaching new audiences by tackling barriers to inclusion.

‘A netful of jewels’: Digital possibilities in museums

Throughout the 1990s there were discussions in the UK cultural and educational sectors about how multimedia and digital technologies, such as online museum catalogues, might enable audience development.73 It was felt that digital technologies could help the circulation of scholarship through digital publishing and the ability to access collections online; could enhance the communication and administration systems within arts organisations through intranet systems and email; and could create better communication between different organisations. This vision for digital was entangled with policies at the time centred around ‘social inclusion’.74 After they were elected in 1997, the New Labour government began to implement their long-term manifesto ‘for the many not the few’. This involved setting up a ‘Social Exclusion Unit’ through which they pledged to increase social inclusion by removing the barriers that limited people’s access to culture, ‘particularly by virtue of the area they live in; their disability, poverty, age, racial or ethnic origin’.75 This involved implementing measures such as removing admission charges to museums and galleries,76 investing in more audience-centred programming in museums, galleries, libraries and archives77 and encouraging them to tackle ‘social exclusion’ by acting ‘as agents of social change in the community’.78 Information Communication Technology (ICT) was seen as one way in which museums could give audiences greater access to culture and education. A report published by the government Department for Culture, Media and Sport in May 2000 recommended that arts organisations ‘make full use of ICT as a means of making their collections more accessible’ and that ‘catalogues and key documents should be available on-line via the internet’.79 These policies were then implemented in museums, galleries, libraries and archives in the 2000s, but they were also part of a trajectory that connected technology, museums and audiences.

Through these digital initiatives, which included making collections available online, it was also felt that knowledge held by curators could be made more interactive and more widely accessible.80 In a 1992 Arts Council report on interactive technologies used in museums on the West Coast of the US, Sandy Nairne, who later became Director of Programmes at Tate, questioned whether art museum insiders were doing ‘everything possible to disseminate the material and information that they control’.81 He stressed the need for museums to create more ‘active engagement’82 with audiences and to ‘deepen the experience of visitors’,83 and argued that making information more accessible and interactive would enable museums to collaborate with universities and artists.84 As digital heritage scholar Andrea Sartori has observed, the ‘fluidity and variability of the Web’ was transformational for the perception of the knowledge held by museums.85 It ‘posed threats, but also challenges’ to the authoritative voice of the museum and ‘forced’ them ‘into “awareness that they are no longer the sole interpreters of their collections”’.86 By the late 1990s, museums and galleries were looking for ways to engage audiences with their new ‘sites’ and one way they found of doing this was by curating artworks online. Net art seemed a perfect fit, as it appeared to embrace and share the democratising of museum-based knowledge and information.

The launch of museum websites in the late 1990s coincided with the dot-com boom – a period of massive growth in internet-based companies that was fuelled by stock market speculation – and it is important to recognise that in the UK there was an economic potentiality to working online, alongside the benefits to access and inclusion. Tate had sponsorship from BT for the website from its launch in 2000 until 2012, and in 2000 the museum proposed a major income-generating initiative with the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York, named Project Muse. This was a website that would sit between Tate’s and MoMA’s sites through which people could have access to knowledge about the collections as well as the chance to buy art and designer products. Project Muse failed to materialise partly as a result of the collapse of the dot-com boom around that same time, but the proposal speaks to the scale of vision and potential that the web held for the museums. The combined and shifting potentiality of the online environment at Tate, oscillating between commerce and inclusion, has been reflected on by Andrew Dewdney, David Dibosa and Victoria Walsh in their important 2013 book Post-Critical Museology: Theory and Practice in the Art Museum. One of the factors the authors identify as contributing to the failure of the UK government’s inclusion agendas both in society and within the cultural sector was the use of digital, which has come to epitomise ‘the business and busyness of the digitization of everything along existing institutional and organizational lines’.87 While digital was used by Tate in the naming of Digital Programmes (as it was by other organisations) to highlight access to information and the potential for interaction, it simultaneously functioned to remove interaction: as Dewdney, Dibosa and Walsh observe, ‘digital heritage brackets out a consideration of visitor experience. It ignores the wider sense of convergence in digital form of all cultural content and, crucially, in the digitization of broadcast and entertainment media … meaning is reduced to consumption.’88 To what extent did this affect the curatorial approach to the net art commissions at Tate?

The institutional set-up for the commissions

Figs.9a and 9b

Screenshots of the Tate website in June 2001, showing the net art commissions indexed under ‘Art Projects Online’ then ‘Net Art’

Wayback Machine

Digital image © Tate

Photograph featured in fig.9a: Giuseppe Penone/Paolo Mussat Sartor

Tate’s net art commissions were available on the Tate website from 2000 to 2002, indexed under ‘Tate Connections’ and then within ‘Art Projects Online’, with a URL that referenced ‘Web Art’. From 2002 to 2008 a tab for ‘Net Art’ was included on Tate’s homepage, with a URL featuring the words ‘Net Art’ (figs.9a and 9b). Here the artworks were accompanied by a biography of the artist, a brief description of the work, a representative still image and a text commissioned by an artist, historian, or media or net art critic. As mentioned earlier, they were initially curated by individuals within the National and International Programmes department, and from 2001 by the Digital Programmes team, a new division positioned within the department of National and International Programmes. As Director of Programmes, it was Sandy Nairne’s role to oversee the Digital Programmes team as well as Tate Liverpool, Tate St Ives and the Tate Britain redevelopment. This combination of overseeing the organisation’s national and international remit along with the digital programme is significant for the way that the latter would take shape and the institutional context in which the net art commissions initially sat. From previous experience, which included directing the visual arts programme for the Arts Council (1988–1992), Nairne understood that there would be a feeling of ‘outrage’89 in the UK that the government was funding another national museum in London. In recognising this, it was vital that Tate demonstrate what this new, digital part of the museum could offer audiences outside London, both in the UK and internationally.90

From the start the Digital Programmes team included people with both curatorial and technological expertise.91 Matthew Gansallo, who trained as an artist and had an interest in architecture and new media, was brought in as Senior Management Research Fellow in 1998. Gansallo, who has spoken on a number occasions about his experience of the commissions, has described the potential of his position in the early days of Bankside before it became Tate Modern: ‘I could cover all grounds – development as well as curatorial; I could go around and do all sorts of things.’92 This movement across the organisation also brought sense of campaigning: ‘I was the conduit for five of six departments and had to tell them what we were doing’.93 Jemima Rellie, an art historian who had put herself through night school in Shoreditch to learn software programming with artists Thomson and Craighead, was appointed as Head of Digital Programmes in 2000. Among a range of responsibilities, it was Rellie’s job to run the programme of net art commissions, something she did in collaboration with others from 2000 to 2006. Rellie’s papers and writings from this time and subsequently show an understanding of the combined role of website and digital programmes in bridging arts, education, digital publishing and the organisation’s commercial agendas.94

Honor Harger also arrived at Tate in 2000 and was appointed as Curator: Webcasting in the Education and Interpretation department at Tate Modern. Her role involved curating and broadcasting a series of events online, including ‘Surveillance and Control’, ‘Border Crossings’ and ‘user_mode = emotion + intuition in art + design’.95 Traces of these events, like other forms of temporary programming, are now hard to find. They exist only on listservs and on the Wayback Machine (an archive of billions of websites across time), which indicates the precarity of these histories.96 An artist and curator, Harger came from a background of working at the intersection of arts and technology. In 1997 she and Adam Hyde had established Radioqualia, which produces broadcasts, installations, performances and online artworks; she had also worked at the Australian Network for Art and Technology and had collaborated with many artists in Eastern Europe. From this she had built extensive networks in the international net art scene. Given her knowledge and practice Harger was involved in the initial stages of the net art programme, which included the shaping of a Digital Arts Strategy and helping select artists and authors for the texts that would contextualise the artworks.97 When Harger left Tate in 2003, Kelli Alred (then Kelli Dipple) was appointed as Webcasting Curator. Before this Alred had been a performance artist and producer working in Melbourne and curator and media lab manager at Site Gallery in Sheffield. In 2006, Alred moved from her role as Webcasting Curator at Tate to the position of Curator: Intermedia, working on the net art commissions and a broader events-based programme within the department of Tate Media.

The net art programme, 2000–6

In 2000, early on in the creation of the net art programme at Tate, individuals with knowledge and interest in new media were brought in to recommend artists and take part in digital strategy meetings. From Tate, this included Sandy Nairne and Matthew Gansallo along with Tom Betts, Web Editor, and Tanya Barson, Collection Curator. They were advised externally by Matthew Fuller, an artist and media critic, and Lisa Haskel, who since the early 1990s had been organising events around the implications of media technologies at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London.98 In a report written by Gansallo, he outlines the interest this group had in either commissioning an artist whose work was in the collection or ‘an artist who was already working on and with the web using “net-language”’, where there were strong ideas and ‘an interactive element to their works’.99 Barson focused on the collection artists and Haskel on ‘net artists’. From a longlist of twenty-six, a shortlist was drawn up that included collection artists Simon Patterson, Emma Kay and Sven Pahlsson, and ‘new media and technology’ artists JODI (Joan Heemskerk and Dirk Paesmans), irational.org, Olia Lialina, Natalie Bookchin, Keith Piper and Mongrel (a collective made up of Graham Harwood, Richard Pierre-Davis, Mervin Jarman and Matsuko Yokokoji).100 These artists were contacted and invited to write a proposal for creating a work for Tate’s website. The proposals that were received were then reviewed along with examples of the artists’ work. Out of these, Harwood and Patterson were selected, and their works were launched on the Tate website on 26 June and 12 July 2000 respectively.101

Harwood was selected partly on the strength of his work Rehearsal of Memory 1996, an interactive computer programme embodying the collective experience of a group of inmates and staff from Ashford Maximum Security Hospital near Liverpool. The work had been exhibited a few years earlier at Video Positive festival in Liverpool (1995)102 and in Serious Games (1997), an exhibition curated by Beryl Graham and held at the Laing Art Gallery in Newcastle and the Barbican Gallery in London.103 Harwood’s response to Tate’s invitation was to create a website that would peel off ‘the skin/fabric of Tate Britain’s building to reveal the history of how it became a national museum and art gallery’.104 This included a text written by Harwood that exposed Tate’s historic connections to slavery and discrimination of working class people. He also made composite images of Tate paintings and the bodies of his family, friends and members of his network, as well as people who had experienced oppression. Titled Uncomfortable Proximity, the work was intended to appear without warning for every fifth visitor to the website.

Simon Patterson, who was commissioned at the same time, was selected by Gansallo after he saw Patterson’s work in Tate’s exhibition Abracadabra (1999).105 In commissioning Patterson, Gansallo wanted to bring in an artist whose work referenced networked practice but who had never created a work online.106 Patterson’s commission, Le Match des couleurs, plays with information systems exploring ‘the use of sound and colour within the Internet’.107 When the work is launched, colour charts appear on the viewer’s computer screen accompanied by the names of French football teams, which are read out by Eugéne Saccomano, an announcer of football scores in the French League for Radio France 1.

Following this, Rellie worked with Heath Bunting on his BorderXing Guide 2002, a guide to crossing borders in Europe without papers and without being detected, as well as with Susan Collins on her commission Tate in Space 2002, a proposal for a sixth Tate site located in outer space. Both Collins and Bunting had been invited by Rellie to make a proposal for a net art commission that would ‘respond to the historical context of network art; or, respond to context of Tate as a media and communication system, and that might involve significant elements of participation/interaction.’108 Like Harwood, Collins’s work had been included in Video Positive in 1995.109 She also had a consistent gallery presence, with exhibitions at the Laing Art Gallery and her works Suspect Devices 1997 and In Conversation 1997–2001 touring to Fabrica in Brighton (1997) and Chapter Arts Centre in Cardiff (2000).110 Meanwhile, Bunting was deeply embedded in the international net art scene and was exhibiting at an intersection between contemporary arts and net art projects.

Fig.10

Natalie Bookchin and Jacqueline Stevens

agoraXchange 2003

© Natalie Bookchin and Jacqueline Stevens

Fig.11

Shilpa Gupta

Blessed-Bandwidth.net 2003

© Shilpa Gupta

Rellie also commissioned agoraXchange 2003 (fig.10) from political scientist Jacqueline Stevens and artist Natalie Bookchin, a website that acts as a forum for conversations around an imagined game where global democracy would be discussed and practiced. Shilpa Gupta’s Blessed-Bandwidth.net (fig.11) was released at the same time and was a play on the blending of faith and commodity in online environments. Gupta, Stevens and Bookchin had all had recent contact with individuals at Tate and discussed their commissions following an invitation for proposals. Stevens and Bookchin had spoken about their idea at the 2003 symposium ‘user_mode = emotion + intuition in art + design’ at Tate Modern, organised by Honor Harger in collaboration with Central Saint Martin’s College of Art and Design, and Bookchin, like Heath Bunting, was part of the early net art scene.111 Gupta’s work would have been familiar to Tate after her work Sentiment Express was exhibited in Century City. Harger had worked closely on its installation and maintenance, recalling how ‘just getting an internet connection that was supporting an email server into the gallery for that show was a real drama. It was really hard, unnaturally hard.’112

In 2006, Tate began a collaboration with the Whitney’s ‘Artport’ through its curator Christiane Paul, and three new artworks were commissioned: Andy Deck’s Screening Circle, which is an invitation to collectively create a drawing online; Marc Lafia and Fang-Yu Lin’s The Battle of Algiers, an interactive database-driven reworking of the 1966 film of the same name by Gillo Pontecorvo; and Golan Levin’s The Dumpster, an interactive visualisation that drew on data from blogs in which people described their experiences of heartbreak. Before she left Tate in 2006, Rellie’s final project was the commissioning of two works by Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industries, The Art of Sleep and The Art of Silence. Combining black Monaco font on a white background with jazz beats, these works riffed off the language, structures and feeling of being both inside and outside of the art world.

In 2000, before the commission series launched, Nairne, Gansallo, Barson and Betts visited the net_condition exhibition at ZKM Center for Art and Media in Karlsruhe to get a sense of how art might be presented online. As an outcome of this visit the group agreed on the importance of contextualisation: ‘Tate should not risk hosting work which is inadequately contextualised that could lead to a tokenistic or a co-optive approach, making the Tate seem as though it is simply adding on “net art” for the sake of being seen to be doing something in new media and technology.’113 As such, from the start, and following an approach similar to gallery-based curatorial practice, the commissioned artworks were contextualised for audiences through texts. These were produced between 2000 and 2008 and appeared on the net art pages alongside the works they referenced.114 They were written by artists, critics and theorists who were established in the fields of new media, digital arts and sound art, and addressed topics like the relationship between net art and traditional artistic canons, connections between art and activism, identity politics and shifting political environments. For instance, Lev Manovich, author of The Language of New Media (2001), responded to Levin’s The Dumpster with a reflection on how it can be seen to develop literary devices for representing the interior and sociological gaze.115 Josephine Berry, at the time an editor at Mute magazine, placed net art in the context of posthumanism – a theory that looks beyond the human to consider the way people live alongside machines.116 In her article Berry suggests that rather than addressing identity in terms of ‘various groups’, thus reducing it to ‘the molar determinants of nationality, gender, class and race’, the approach of net artists to exploring the information networks was in fact closer to people’s lived experience in a global, networked society. Helen Thornington, an artist who had been working with radio, dance and sound since the early 1970s and later on with the internet (she founded Turbulence.org in 1996), created a connection between experimental practices in sound art and the importance of access and participation on the internet.117 These texts played an important role at the time and subsequently in disseminating ideas emerging from the commissions to audiences who were likely to be unfamiliar with net art practices.

The essays have since helped the commissioned works to be historicised in the fields of media studies, digital histories, comparative literature, curatorial practice, histories of ‘tactical media’ and in a critical analysis of race and identity online.118 These historicisations appear to emphasise forms of mediation, be it digital, bodily or curatorial mediation. Bookchin and Stevens’s agoraXchange has, for example, been interpreted through game theory and in terms of the development of digital humanities and globalisation.119 Levin’s The Dumpster and Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industries’s The Art of Sleep have both been historicised in connection with digital poetry, The Art of Sleep specifically as an example of digital modernism in literature.120 Harwood’s commission has been considered as an exploration of the status of race and cultural action in cyber culture, for the way in which it brings together the body with new media technologies.121 Many of these texts reference or even centralise the commissioned essays in their theoretical engagement with the works, suggesting that a large part of the visibility of these works is owed to the contextualising essays and the fact of their historicisation.

Reframing the net art programme, 2007–11

In 2007 the commissions and accompanying programme were reframed by Kelli Alred within the legacy of ‘intermedia’ arts, a name drawn from the Fluxus artist Dick Higgins’s description of interdisciplinary activities occurring between genres in the 1960s.122 This reframing took place after Alred was appointed Curator: Intermedia Art, Tate Media (2006–11), a role that consolidated her existing work with Rellie on the net art commissions and her work as Webcasting Curator at Tate Modern. Within this curatorial frame Alred’s intention was to resituate net art within a longer aesthetic and conceptual history that included post-1960 debates surrounding the death of the object, the erosion of media hierarchies, and art historian Rosalind Krauss’s concept of the ‘expanded field’.123 Alred explained that this was about showing ‘the breadth of activities that could be understood at Tate as being involved in Intermedia. So, kind of, a richer, looser kind of array that would speak to different audiences in different ways.’124

Alred worked on four further net art commissions as well as a public programme in the gallery and online. She commissioned a second work by Heath Bunting, A Terrorist 2008, which was part of his ongoing work The Status Project and mapped the ways in which identities are constructed through membership of a series of institutions. Martin Wattenberg and Marek Walczak’s Noplace 2008 was ‘sponsored by’125 Tate’s website through Alred, who had already been working with the artists on a previous version of the work. Finally, Alred commissioned Nonrepetitive 2011, an interactive sound work by Achim Wollscheid, who had previously created a new work for the event ‘The Sound of Heaven and Earth’ at Tate Modern in 2005.126 During this period, curator Vincent Honoré also commissioned Watercouleur Park 2007 from the French collective Qubo Gas. This is an interactive watercolour drawing that moves around the screen at different paces and in shifting detail to a musical composition by DJ Elephant Power, Michael Mørkholt and Fan Club Orchestra.

Fig.12

The Intermedia Art microsite within Tate’s website, 2008

Wayback Machine

Digital image © Tate

These commissions were placed alongside the previous ones on the Intermedia Art microsite within Tate’s website designed by Bureau for Visual Affairs in 2008 (fig.12). The microsite also held broadcasts from live programming, interviews and discussions on audio production and distribution in a post-digital environment, and a discussion on curatorial practice in relation to networked art practice.127 Curatorially, the Intermedia programme and its webpages ‘merged online platforms, broadcast, magazine publishing and a special events programme’, according to Alred.128 It followed the concept of a magazine and had two themes a year on average.129 This framing was informed by a shifts taking place in the Curatorial department at Tate that saw a move towards ‘ephemeral’130 practices through an increase in live events such as performance, film, video, radio and net art. To reflect this ‘aggregation’ of curatorial practice, co-organised events were held, some of which were promoted and documented on the Intermedia webpages. This included Musicircus in 2006, with works by John Cage, Marina Rosenfeld and La Monte Young, and two events in 2008: Unprojectable by Tony Conrad and a ‘Sound Art’ series by Ultra-red, a sound art collective founded in 1994 by two AIDS activists.131 Over time, however, performance and film programmes led by Catherine Wood and Stuart Comer bedded into the organisation, while net art slipped out of focus. In addition, with the shift of the new artworks to the Intermedia Art microsite, new gaps in the history of net art at Tate were created. Webcast events such as the aforementioned 2003 symposium and festival ‘user_mode = emotion + intuition in art + design’, the mini-conference ‘Wireless Cultures’ (2003), the seminar ‘Border Crossings’ (2002), as well as an essay by Heidi Reitmaier on Shilpa Gupta’s work, did not make it onto the new microsite. With the loss of the net art commission records there is no documentation to indicate why these decisions were made, but given the emphasis on curators reframing the programme through the Intermedia Art site, these absences could well be a result of curatorial selection.

Alred’s change in job title and her curatorial reframing of the net art programme into Intermedia Art coincided with structural shifts at Tate. Between 2002 and 2009, Will Gompertz had begun to build the Tate Media department. Gompertz, who came from a background in publishing, saw Tate as a ‘content business’ and proposed to Tate Trustees that ‘Tate Media should develop production facilities and become a broadcaster and publisher as the best way forward in developing [the organisation’s] online presence.’132 This included the launch of the Tate Channel and Tate Shots. In 2010, the year after Gompertz left Tate, John Stack (Head of Tate Online from 2004) presented a new online strategy, proposing that the website become an interactive ‘platform for engaging with audiences’.133 Integral to this was the idea that digital activities would be dispersed across the organisation. Alred left Tate in 2011; BT’s sponsorship of the website came to an end in 2012 and the site was redesigned that same year by Bureau for Visual Affairs. Among these structural and technological changes, the Intermedia Art pages were relocated to a different server and not updated to be integrated with the redesigned website. As such, while the main website changed in 2012 (as it has subsequently over the eight years that followed), the Intermedia Art pages retained their 2008 design. The result is that these pages and their contents have become records of a moment in time, rather than things that live in the present.134

Changes to the website and decisions as to what not to migrate are a reflection of what does and does not fit into the institution’s brand and its strategic aims at a given time. As the authors of Post-Critical Museology put it, pages and content end up in ‘dusty navigational pathways’.135 This burying of material, perhaps for the purposes of a cleaner design or more logical navigation, has a knock-on effect on the practices and activities that are on the margins of the institution’s main activities. It has been suggested by those who were involved in curating the net art commission series, as well as by others, that the shifting visibility of the commissions within Tate is a result of hierarchies of knowledge and power within the organisation.136 Alred has reflected on the ‘slippery’ nature of her role, working between departments, line managers and priorities, as she ‘tr[ied] to push a little at the boundaries’.137 This came with the terrain of working with artists who ‘were pushing really hard … against these kinds of architectures, and infrastructures, and parameters, as they often do with any institution, not Tate specifically.’138 The commissioning of net art by Digital Programmes and then Tate Media, and not the Curatorial department, meant that the commissions operated in a liminal space within the organisation. Less visibility and lower budgets meant greater risks could be taken (Harwood’s disruption of the website is one example), but equally this meant limited recognition of the programme within the institution. As Gansallo put it, ‘museums the size of the Tate and others only want to engage with [net art] as far as it is an adjunct’ rather than as part of ‘the core of the history of art’.139

Conclusion

Tate’s net art commissions became possible because of shifts in the organisation, a new website, the opening of Tate Modern and the redevelopment of Tate Britain. They are connected to cultural, educational and political agendas in the UK at the time that were focused on increasing levels of access and ‘inclusion’ to the arts, education and culture. These agendas helped drive people in the organisation to find new ways of engaging people with the website. They also filtered down into an initial emphasis on interaction and participation in the Tate net art commissions.

The shifting, liminal position of the departments commissioning net art within the institution – first Digital Programmes then Tate Media – had an effect on the people who worked in the department, as well as the broader perception of the commissions within Tate. At different stages the commissions became more visible inside the institution – on the front page of the website in 2002, through the new microsite in 2007, and through events and cross-departmental programming with performance and film – and outside of the institution, when the commissioned works were used as case studies in histories and explorations of new media and digital arts practice. Equally, there are moments when they became buried: at the start, the commissions were hard to locate as they were situated within ‘Tate Connections’, which was linked to from the homepage. Similarly, in the curatorial framing of Intermedia Art from 2007, elements of the previous webcasting programme (as well as other aspects) were excluded from the online archive. There was also the removal of the Intermedia Art pages from the main server onto www2.tate.org.uk with the redevelopment of the website in 2012, and the loss of the institutional records for the commissions.

These shifting moments of visibility and invisibility demonstrate what was prioritised by the organisation or curators of the commissions at different moments in time, and what elements fell out of view as a result. By bringing back some of what has slipped away, we can find greater complexity, a more satisfying mess, and perhaps lines of institutional enquiry. For example, highlighting the participatory public art commissions by Anna Best and by Nina Pope and Karen Guthrie helps to connect the evolution of Tate’s net art to a reconsideration of public art and socially engaged practice in the late 1990s, as well as to a concern for the impact and inclusion of people living in close proximity to Tate.

Despite the migration to a secondary server, the net art series has persisted. Why? Perhaps because it has a finite beginning and end, it is archived and ready to explore and, as of 2020, it is preserved thanks to Sarah Haylett, Chris King and Patricia Falcão as part of Reshaping the Collectible. The series of commissions also persists because something about its history and the works feels unresolved, something that I think has to do with always being partly inside and outside of institutions, but also the reluctance of many museums to have a clear position on the works. Net art has been ignored by Tate and other UK museums not just because it is resistant to the structures that those systems and practices offer, but because those systems and practices have been unwilling to change. Net art is ‘context-generative’;140 its ongoing care, curation and preservation requires regular dialogue with practitioners and their networks when there are technical faults, when options are needed for upgrading if programmes become obsolete and when changes need to be made to display. This is time consuming and resource-intensive and requires an interest and engagement in the works in order for them to be maintained. With net art now being formally acquired by Tate through the acquisition of Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industries’s The Art of Sleep and The Art of Silence, we have an opportunity to ask some key questions. What might an understanding of how context, network and collaboration operate in net art bring to the collection and its practice? What systems and practices need to change for net art to live in the museum?

In part, change can come by acknowledging the importance of collaboration in conservation and curation.141 In her keynote lecture at the ‘Lives of Net Art’ event at Tate Exchange in April 2019, Christiane Paul recommended that Tate collaborate with those individuals, collectives and organisations that have an understanding of net art or digital arts practices.142 This approach is also stressed by researcher and curator Annet Dekker, whose recommendations include ‘integrating artist strategies into museum practice’, with more focus on the creative process and greater emphasis on ‘the roles and responsibilities of curators and collectors’ – in museums as well as with individuals and collectives beyond them.143 Using and exploring collaboration as a strategy for care in the museum would help reflect the nature of these relational artworks and the approach of practitioners who embrace human and non-human, cross-disciplinary entanglement. The works themselves demonstrate the effects of collaboration or co-production across disciplines. In framing a discussion on a potential new utopia without state borders, Bookchin and Stevens’s agoraXchange is socially and politically engaged, while Bunting’s BorderXing Guide is a documentation of a performance and has a relation to land art, and Susan Collins’s Tate in Space, as a mimesis of Tate’s website, is a form of speculative fiction. All of the works engage with the web as a social environment. Many are connected to activism, a few address issues of discrimination by race or by class, and some present a legacy of institutional critique or visions of utopias. These are some of the themes and ideas through which the works could find connections with non-net art in the wider Tate collection.

The Tate net art commissions and the curatorial approach are, however, not without criticism. Although risks were taken, they were relatively safe: the works were commissioned from artists who were familiar to the institution or its curators, and whose work had already been validated in net art circles or by other cultural institutions. With a few exceptions, on the whole they were biased towards North American and British perspectives. No Black artists were commissioned beyond those in collectives, nor any artists from Eastern Europe, although these had initially been proposed. Some works have lasted longer than others, aesthetically and conceptually, while others need a large amount of contextualisation before they can be understood, interpreted and experienced.

Writing in Art Monthly in 2019, curator Morgan Quaintance highlighted the ‘acritical and apolitical’ surveys of net art and post-internet art, citing Rhizome as an example. A cause and consequence of this is that writers on net art use descriptive approaches, repackaging and repeating previous texts, making the field ‘relentlessly mediated’.144 A political or activist position certainly underpins the broader practices of many of the artists commissioned by Tate: in the works they made for Tate’s series, this was overt in some cases (for instance, Gupta’s Blessed-Bandwith.net, Harwood’s Uncomfortable Proximity, Lafia and Lin’s The Battle of Algiers, Bookchin and Stevens’s AgoraXchange and Bunting’s BorderXing) and more subtle in others (such as Deck’s Screening Circle and Wollscheid’s Nonrepetitive). The present account has to some extent fallen into the trap of being apolitical, touching only briefly on the political drive behind some of these works,145 but it has hoped to emphasise in more depth the environment of the institution, the surrounding curatorial context and the intentions behind the commissions. What this reveals is that in curating the works around a desire to engage audiences (through participation and interaction), rather than, for example, inviting artists to take a political position, a constraint was placed on the breadth of the artists commissioned as well as the scope of the works themselves.

Like Quaintance, I have noticed the tendency towards repetition in writing on this history and these works; it feels like a process of reading existing material, relaying and adding to it. Yet I would argue that repetition is necessary because these histories and works are not yet familiar, and with each repetition there is the potential for difference. The practices of ‘relentless mediation’ that Quaintance highlights – through curatorial choices, technologies, artistic approaches and networks – are part of these net artworks’ shifting historical situation and also offer a plurality of perspectives that we can embrace.