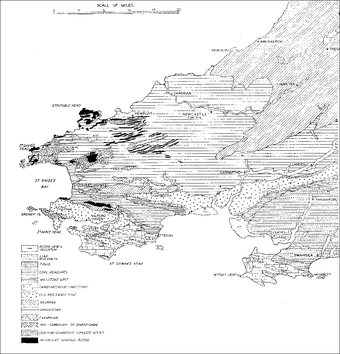

Detail of a geological Ordnance Survey map from 1969 similar to the ones used by Robert Smithson and Nancy Holt on their English journey

Simon Grant

In late August 1969 you and your husband Robert Smithson visited England. Why did you come?

Nancy Holt

Primarily because Bob was in the show at the Institute of Contemporary Arts called When Attitudes Become Form, which opened at the end of September.

Simon Grant

During that month you did a lot of travelling around England, including Wiltshire, Dorset, Devon and Wales. One of the first places you visited was Oxted chalk quarry in Surrey. Why Oxted?

Robert Smithson's Chalk Mirror Displacement constructed at the Oxted chalkpit quarry, Surrey, and photographed by the artist 1969

© Estate of Robert Smithson, VAGA, New York/DACS, London 2012

Nancy Holt

Bob wanted to make a work using chalk and needed to find the right quarry. I think it was someone from the ICA who took us there. I clearly remember Bob making the outdoor version of Chalk Mirror Displacement 1969 and taking photographs of it. He was, of course, fascinated by quarries, and took great interest in geology and palaeontology – just south of the Oxted quarry dinosaur remains were unearthed in the early nineteenth century. Bob knew chalk is composed of millions of compressed prehistoric sea creature skeletons from ancient seabeds. He also loved geological survey maps. We had some with us, so he would know where to find the kind of stone and earth foundations he was looking for.

Simon Grant

After installing the ICA piece, you visited ruins and ancient sites in the south and west of England. One of the places you stopped at was Old Sarum, the Iron Age hill fort near Salisbury…

The ruins at Old Sarum, Salisbury, Wiltshire, photographed by Nancy Holt 1969

Nancy Holt

I’ve had a long-lasting interest in archaeological sites. Old Sarum is an awesome place. We saw land forms, especially the banks and ditches, which functioned for a culture that existed more than 3,000 years ago. You can feel the layers of human history as you stand on the ancient ruins. Bob and I were both fascinated by how the landscape over long periods of time has been changed and reformed by human beings out of necessity, not just as something to look at. I had already done my piece Stone Ruin Tour 1967 and 1968, which consisted of taking a small group of people on a tour of a crumbling labyrinthine garden with stone walls, overlooks, and disappearing stairways, in the woods of northern New Jersey. And I had made a series of photographs of old American West graveyards. Each grave is unique, with most of them surrounded by dilapidated fences of various materials and styles. Seeing the ruins in England reinforced my interest. You have to remember that we Americans live in a young country, so we don’t get to see many of the ruins of Western civilisation. We do, however, have extraordinary Native American ruins, such as those at Chaco Canyon in New Mexico, near where I live.

The ruins at Old Sarum, Salisbury, Photographed by Nancy Holt in 1969

© Estate of Robert Smithson, VAGA, New York/DACS, London 2012

Simon Grant

You travelled to Dorset where you saw the Cerne Abbas Giant, and nearby you visited the village of Milton Abbas with its abbey and large house – the village and grounds were co-designed by Capability Brown.

Nancy Holt

Bob researched in advance some of the places he wanted to explore. At the time we were both interested in the ideas about the Picturesque put forward by the Reverend William Gilpin, as well as Uvedale Price’s Essay on the Picturesque 1794. Price, like Capability Brown, understood how to work with the landscape – to work as nature’s agent.

Simon Grant

Just before your British trip, Bob made a series of photoworks – the Yucatan Mirror Displacements. The photographic process, as well as his preoccupation with mapping and revealing layers of time and space and blending the symbolic and the literal, seemed central to these. He made a similar work in Dorset, didn’t he?

Robert Smithson's Mirror Displacement constructed on Chesil Beach, Dorset and photographed by the artist 1969

© Estate of Robert Smithson, VAGA, New York/DACS, London 2012

Courtesy Nancy Holt

Nancy Holt

Yes. This Mirror Displacement was at Chesil Beach. It consisted of eight mirrors that reflected the rounded rocks and pebbles, while capturing the light in a glowing way. These works have become much more significant than even Bob anticipated at the time. Back then we used an Instamatic camera and shot our slides with Kodachrome film. It is interesting to think about the fact that an artist takes his material with him into the landscape, sets it up, makes a sculpture and then photographs it, and the photograph becomes the art. The landscape and the art can shrink to the size of something you can put in your pocket – the size of a slide.

Simon Grant

Chesil Beach was not the only natural rural environment that inspired both of you. There were some memorable experiences in Devon…

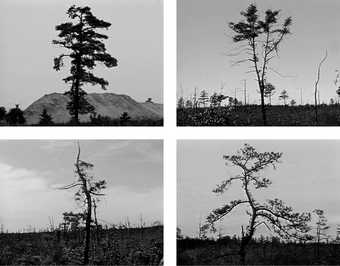

Nancy Holt Trailmakers (7) 1969

Series of twenty inkjet prints on archival rag paper

Edition of three, each 55.9 x 55.9 cm

© Nancy Holt, /VAGA, New York/DACS, London 2012

Nancy Holt in Wistman's Wood, Dartmoor, photographed by Robert Smithson 1969

Courtesy Nancy Holt

Nancy Holt

We went to Dartmoor National Park, where I made several works, including the series of photographs Trail Markers. I followed the orange circles painted on rocks or fence posts guiding you along the walking route and took photographs. I hadn’t seen markers like these before. I didn’t know if they were unique to this place or not, but in any case they lent themselves to my project. We had never been to any place like these moors before. As a matter of fact, we felt that the whole trail – the moors, the rocks and the sheep – was otherworldly. At one point we reached Wistman’s Wood, an ancient woodland of stunted oaks. I believe the name Wistman originated from the dialect “Wisht”, meaning eerie, haunted or enchanted. (By the way, ‘Holt’ in old English means ‘a wood’.) I remember that the ground was strewn with large rocks covered with many different types of mosses and lichens, out of which arose these strange twisted trees. We were stunned by this place. I did my first Buried Poem #1 (for Robert Smithson) piece there. A site evokes a person, and I bury a poem for that person and later the person a booklet including maps, detailed directions and a list of equipment (such as a compass and shovel) in order to find it. To me, Wistman’s Wood conjured up Bob’s persona in a striking way…

Robert Smithson in Wistman's Wood, Dartmoor, photographed by Nancy Holt 1969

Courtesy Nancy Holt

Simon Grant

In what way?

Nancy Holt

Well, he did have a rather bifurcating mind, which, like the gnarled oaks, was rooted in the ground and the rocks – like his being expressed in nature. It was to be an inspirational place for me. I also took photographs of the wood, and later, back in the USA, I made my film Pine Barrens 1975, which I filmed in a wilderness area in New Jersey called the Pine Barrens, which also has stunted trees. There is uncanniness there too, and local tales of a Jersey Devil lurking in the woods. Looking back, I feel that the Pine Barrens film may have been seeded in our visit to Wistman’s Wood. Walking on that Dartmoor trail was a pivotal experience. Not long before our visit there, we had seen Stonehenge, Avebury and Silbury Hill. It all works on the psyche.

Four film stills from Nancy Holt's Pine Barrens 1975

© Nancy Holt/ VAGA, New York/DACS, London

Courtesy Haunch of Venison Gallery, London and New York

Simon Grant

You were both fascinated by the ruins of mines and quarries and declining postindustrial landscapes, and Bob wrote memorably on this subject. In the UK in 1969 there would have been many places such as this, especially in and around the disused coal mines in the Welsh valleys. Where did you go?

Robert Smithson's Untitled (Zig-Zag Mirror Displacement) 1969, probably constructed and photographed at the abandoned open-cast mine near Tredegar, Wales

© Estate of Robert Smithson, VAGA, New York/DACS, London 2012

Nancy Holt

Besides the books on prehistoric monoliths in Europe and England that we had brought with us, Bob also had a book on Welsh mines. We visited many gravel pits and quarries, often quite out of the way. One place labelled Ash Hill on one of the slides is likely where Bob made a mirror piece called Untitled (Zig-Zag Mirror Displacement), probably on the outskirts of Tredegar. We found these abandoned, edge-of-the-world places intriguing; mines that had at one time railroad tracks and tunnels to transport rock. These structures are now overgrown and broken down. Bob and I both grew up in northern New Jersey, where you could find hidden quarries, forbidden places, scattered throughout the landscape. The coal mines in Wales were like that too. These so-called depressing, forgotten places that fall within the gaps of one’s consciousness are often described negatively. But if you look at them with a neutral eye, you start to see them differently; you begin to see a beauty in their entropic condition. What I remember most about being in Wales was the language. Often the people we met didn’t speak English, or spoke with a heavy accent that made it difficult for us to understand them. The road signs in the back country were mostly in Welsh – we often didn’t know where we were going, which could be useful when we couldn’t understand a ‘no trespassing’ sign.

Simon Grant

Of course Wales is also rich in ancient sites…

Nancy Holt

We went to Pentre Ifan, the Bronze Age megalithic site that is made of the same rocks that form the blue stone ring at Stonehenge. We were awed, just like we were when we went to the Avebury Rings, Silbury Hill, Stonehenge and Cerne Abbas. And along the route we saw many earthworks and burial mounds. Looking back on it, our trip was quite significant for both of us, and has had a lasting effect.

Simon Grant

Bearing in mind how you both experienced the American landscape, how did you feel about the English landscape?

Book cover of Mark Girouard's Robert Smythson: Art and the architecture of the Elizabethan Era (1966) from the Robert Smithson library

Nancy Holt

I think we identified with what we saw and felt an historical connection with the earth at that place on the planet, as we both have English backgrounds. Bob’s great grandfather Charles Smithson had grown up in northern England and had apprenticed as an ornamental plasterer before moving to the US. (The company he founded was commissioned to do the ornamental plastering work in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Natural History and the New York subway system, among many others.) There were other Smithsons further back, possibly his relatives – including Robert Smythson, the great pioneering sixteenth-century architect of Hardwick Hall and Longleat House, and later, James Smithson, who endowed the Smithsonian Institute in the USA and was also a mineralogist after whom Smithsonite is named. (Interestingly, Franklin Furnace quarry in New Jersey, where Bob got the rocks for one of his early Non-Sites, is one of the few places in the world where Smithsonite has been found.) My grandfather Samuel Holt came from Eccles in Lancashire. He trained as a textile designer at Manchester Technical School, before emigrating to Massachusetts in the 1890s to teach textile design for more than 40 years.

Simon Grant

After your journey you travelled back to London for the opening of the ICA show…

Nancy Holt

Yes, but it’s odd – I don’t really remember much of my time in London. It was the landscape that engaged me the most.