Sorry, no image available

In Tate St Ives

- Artist

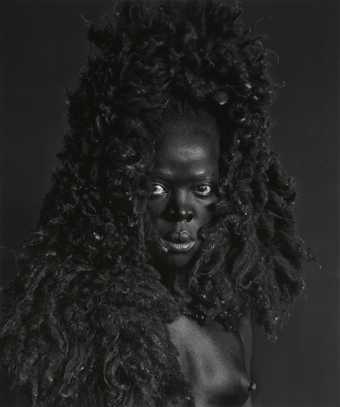

- Zanele Muholi born 1972

- Medium

- Photograph, gelatin silver print on paper

- Dimensions

- Image: 297 × 217 mm

support: 422 × 345 mm - Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Purchased with funds provided by Priti Chandaria, Emile Stipp and Mercedes Vilardell 2017

- Reference

- P82048

Summary

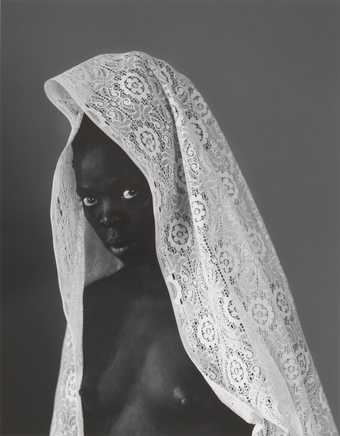

This is one of a group of black and white self-portraits in Tate’s collection from the ongoing series Somnyama Ngonyama, in which Zanele Muholi portrays themself in a variety of guises, with a range of props and adornments and against diverse backgrounds (Tate P82041–P82049).

Muholi began this ongoing series in 2012 while travelling as a way of marking their presence in different spaces. The series, however, took off in 2014 when Muholi decided to create 365 self-portraits, each responding to different physical environments, histories and personal experiences, in order to confront the politics of race and representation. In some photographs, such as Thembitshe, Parktown (Tate P82047) Muholi poses against plain backgrounds wearing only a single item – in this case a cosmetics bag turned inside-out on their head. In others, they appear against graphically-patterned backgrounds, wearing everyday objects that when recontextualised become historically loaded props. In Thembekile, Parktown 2015 (Tate P82046) a white extension cord is looped around their neck; in another they have decorated themself with strips of white masking tape across their torso and hair. The titles are in Zulu, the artist’s home language, and usually reference the geographical location where they were made.

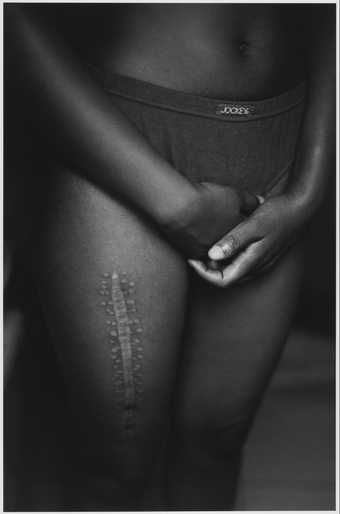

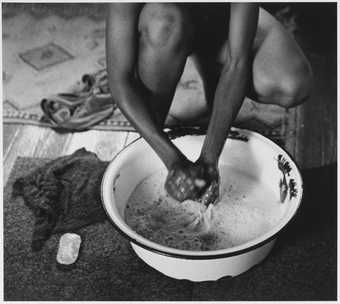

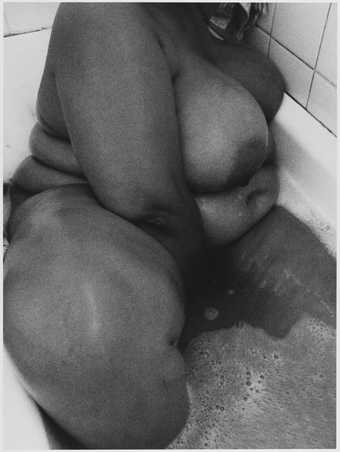

In their work as a photographer and self-identified ‘visual activist’, Muholi focuses on the experiences of the black LGBTQI+ community in South Africa. In the series Only Half the Picture 2003–6 (Tate P81289–P81294) they realised this through close-up, intimate and mostly anonymous studies of women’s bodies and in Faces and Phases 2006–ongoing through portraits of black lesbian and transwomen accompanied by first-hand testimonies (written and audio) that document the participant’s individual experiences. While Muholi continues to address socio-political themes through portraiture in Somnyama Ngonyama, this body of work is more autobiographical and diaristic than previous projects. They have described this as follows:

Somnyama Ngonyama (meaning ‘Hail, the Dark Lioness’) is an unflinchingly personal approach I have taken as a visual activist to confronting the politics of race and pigment in the photographic archive. It is a statement of self-presentation through portraiture. The entire series also relates to the concept of MaID (‘My Identity’) or, read differently, ‘maid’, the quotidian and demeaning name given to all subservient black women in South Africa.

(Muholi, Somnyama Ngonyama, accessed 9 July 2016.)

Since 2012, when Muholi began the Somnyama Ngonyama series, they have experimented with a range of personas and archetypes. Muholi has explained that ‘the black body itself is the material. The black body that is ever scrutinised and violated and undermined’ (Emine Saner, ‘”I’m scared. But this work needs to be shown”: Zanele Muholi’s 365 Protest Photographs’, Guardian, 14 July 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2017/jul/14/zanele-muholi-365-protest-photographs, accessed 19 March 2019). In each of the images there is a saturated and unapologetic blackness achieved through deliberately toning down any highlights, exaggerating the darkness of Muholi’s skin tone. Muholi’s penetrating gaze forces the viewer into a dialogue with the work.

Further reading

Zanele Muholi, Zanele Muholi: Somnyama Ngonyama, Hail the Dark Lioness, 2018.

Zanele Muholi, Somnyama Ngonyama, Stevenson Gallery, Cape Town, e-book, https://issuu.com/stevensonctandjhb/docs/muholi_somnyama_ngonyama_pdf_book_i, accessed 9 July 2016.

Jenna Wortham, ‘Zanele Muholi’s Transformations’, New York Times, October 8 2016 http://www.nytimes.com/2015/10/11/magazine/zanele-muholis-transformations.html?_r=0, accessed 9 July 2016.

Emma Lewis

May 2016, updated March 2019

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

You might like

-

Adam Broomberg, Oliver Chanarin Untitled (Two women hiding)

2010 -

Adam Broomberg, Oliver Chanarin Untitled (People saluting)

2010 -

Adam Broomberg, Oliver Chanarin Untitled (Boy running with barrel)

2010 -

Adam Broomberg, Oliver Chanarin Untitled (Fountain)

2010 -

Zanele Muholi ID Crisis

2003 -

Zanele Muholi Bra

2003 -

Zanele Muholi Aftermath

2004 -

Zanele Muholi Ordeal

2003 -

Zanele Muholi In-security

2003 -

Zanele Muholi Flesh II

2005 -

Zanele Muholi Thembeka I, New York, Upstate

2015 -

Zanele Muholi Bona, Charlottesville

2015 -

Zanele Muholi Somnyama IV, Oslo

2015 -

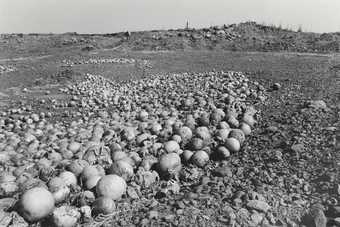

Santu Mofokeng Undersized, Stunted-in-Growth and Rotting Melons Dumped in the Veld Outside Kroonstad, Free State

2007, printed 2011 -

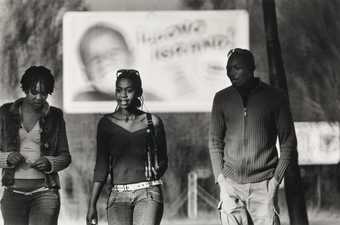

Santu Mofokeng Street Scene - Rockville

c.2004, printed 2011