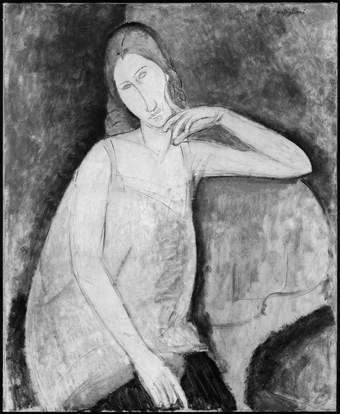

Fig.1

Unknown photographer

Jeanne Hébuterne, c.1914

© Archives Jeanne Hébuterne

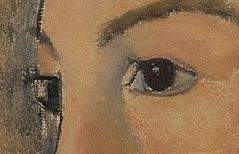

Jeanne Hébuterne (fig.1) was a few months shy of her nineteenth birthday when she met Amedeo Modigliani in Paris in late 1916 or early 1917. Now best known for being Modigliani’s model, partner and the mother of their daughter Jeanne, Hébuterne was an art student when she met the artist, who was then about thirty-two. Her friend, the Ukrainian sculptor Chana Orloff, probably introduced them when both women were studying at the Académie Colarossi in the Montparnasse neighbourhood of Paris, near to where Modigliani lived.

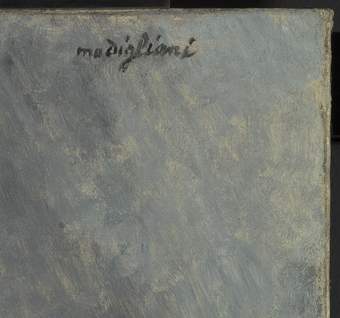

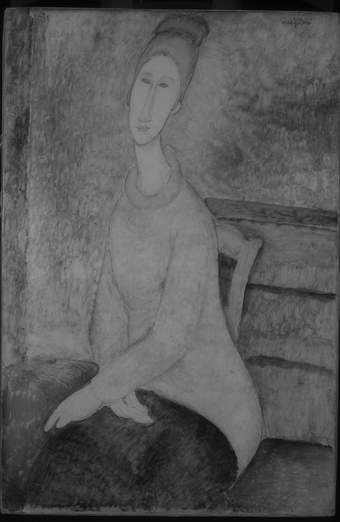

Fig.2

Jeanne Hébuterne

Self-Portrait c.1917

Oil on board

445 x 305 mm

Private collection

Public domain

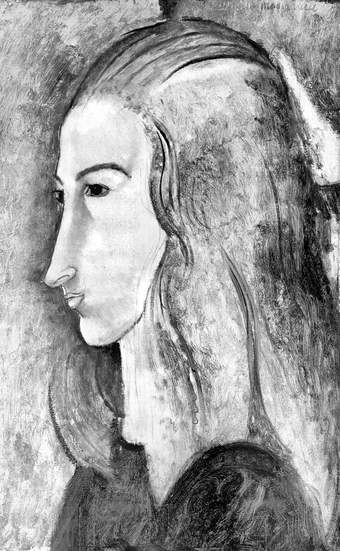

Fig.3

Jeanne Hébuterne

Self-Portrait c.1918

Oil on canvas

550 x 330 mm

Private collection

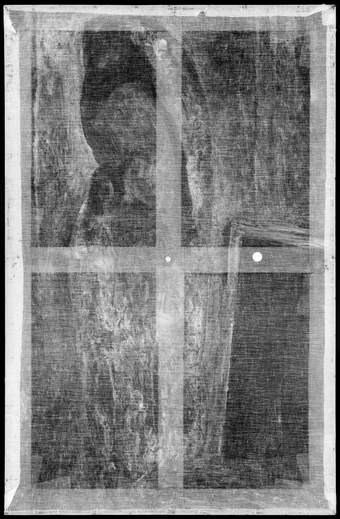

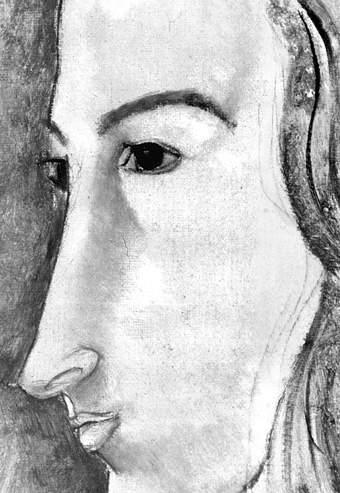

Hébuterne’s early paintings, of which only a handful of examples survive, demonstrate stylistic similarities to the work of the Fauves and the Nabis, as seen in her self-portrait from c.1917, which features her characteristic pale blue eyes and thick red tresses (fig.2). A second self-portrait, probably from around 1918, appears to indicate the influence of Modigliani’s characteristic style, with its elongated neck and face, and almond-shaped eyes (fig.3). Given her self-assured painting style, however, it is possible that a genuine artistic dialogue existed between the two artists and that Hébuterne encouraged Modigliani’s artistic production in the last years of his life.

To the disapproval of Hébuterne’s middle-class Catholic family, she began living with Modigliani months after they met. While the large number of works in which Modigliani represented Hébuterne might suggest his devotion to her, it is also indicative of her ready availability as a model. As with Paul Cézanne’s portraits of his wife, Hortense Fiquet, Modigliani’s portraits suggest that Hébuterne was a reliable collaborator in this respect. She posed for him on at least twenty-six occasions both in Paris and during their sojourn in the South of France between spring 1918 and the early summer of 1919, considerably more frequently than any other sitter. As would befit a woman of her social status, there are no known nude portraits of Hébuterne by Modigliani nor any known examples of portraits of her by other artists. By closely examining several portraits of Hébuterne by Modigliani in conjunction with biographical details, this study reveals new insights into Modigliani’s working practice, his stylistic development during the last years of his life, and the changing image of Hébuterne as she evolved as an artist and became a mother.

It is difficult to establish a solid chronology of the portraits of Hébuterne, and the dates assigned to them in the various catalogue raisonnés and publications are inconsistent.1 They were painted within a short time period – the majority are currently dated to 1918 and 1919 – during which Hébuterne went through two pregnancies. She gave birth to Jeanne in Nice on 29 November 1918, and by the summer of 1919, she was pregnant once again. She ended her life on 26 January 1920, two days after the death of Modigliani, and when she was nine months pregnant with her second child. The technical analyses presented in this article contribute to a more solid chronology of the portraits by providing evidence as to where they may have been painted and of Modigliani’s subtle stylistic development during the last two years of his life.

Scope and results of the technical study

Fig.4

Amedeo Modigliani

Portrait of Jeanne Hébuterne 1918

Oil on canvas

997 x 648 mm

Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia

C261

Public domain

Fig.5

Amedeo Modigliani

Jeanne Hébuterne 1919

Oil on canvas

1003 x 654 mm

Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia

C307

Public domain

Fig.6

Amedeo Modigliani

Jeanne Hébuterne 1919

Oil on canvas

914 x 730 mm

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

C326

Public domain

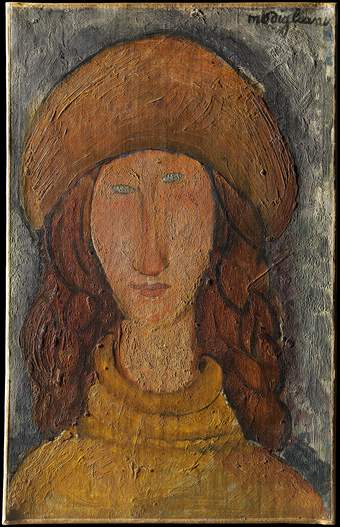

Fig.7

Amedeo Modigliani

Jeanne Hébuterne with Yellow Sweater 1918–19

Oil on canvas

1000 x 647 mm

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

C220

Public domain

Fig.8

Amedeo Modigliani

Portrait of Jeanne Hébuterne 1919

Oil on canvas

460 x 290 mm

Musée d’art Moderne de Troyes, Troyes

C327

© C2RMF / Gérald Parisse

Fig.9

Amedeo Modigliani

Portrait of a Young Woman 1918

Oil on canvas

460 x 280 mm

Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven

C224

Public domain

Of the twenty-six known portraits of Hébuterne, fifteen are three-quarter-length portraits and eleven are smaller bust-length portraits. This study focuses on six portraits held in North American and French institutions, which we examined, imaged and analysed.2 These include four three-quarter-length portraits: Portrait of Jeanne Hébuterne 1918 (C261; fig.4) and Jeanne Hébuterne 1919 (C307; fig.5) from the Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia;3 Jeanne Hébuterne 1919 (C326; fig.6) from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; and Jeanne Hébuterne with Yellow Sweater 1918–19 (C220; fig.7) from the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York; and two head and shoulder portraits, Portrait of Jeanne Hébuterne 1919 from the Musée d’Art Moderne de Troyes (C327; fig.8)4 and Portrait of a Young Woman 1918 (C224; fig.9) from Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven.5

The following table summarises the methods and results of the technical analyses of each of the six paintings, which included pigment, media, ground preparation, varnish, and canvas thread counts. These data form the basis for our discussion and evaluation in the remainder of the article.

|

Portrait of a Young Woman |

Jeanne Hébuterne |

Jeanne Hébuterne |

Jeanne Hébuterne |

Jeanne Hébuterne with Yellow Sweater |

Portrait of Jeanne Hébuterne |

|

| Identification methods (with abbreviations) |

Macro-XRF (M), handheld point XRF (P), FTIR spectroscopy (F), SEM-EDX (S), Raman spectroscopy (R), optical microscopy (Mi), visual examination (V) * Indicates where additional analyses are necessary for a firm identification (e.g. Raman spectroscopy) |

Macro-XRF, unless Raman spectroscopy (R), SEM-EDX (S) or visual examination (V) are indicated * Indicates where additional analyses by Raman spectroscopy, X-ray diffraction (XRD) and/or SEM-EDX are necessary for a firm identification |

Macro-XRF (M), handheld point XRF (P), FTIR spectroscopy (F), Raman spectroscopy (R), visual examination (V) * Indicates where additional analyses are necessary for a firm identification (e.g. Raman spectroscopy and/or SEM-EDX) |

Macro-XRF (M), handheld point XRF (P), FTIR spectroscopy (F), Raman spectroscopy (R), visual examination (V) * Indicates where additional analyses are necessary for a firm identification (e.g. Raman spectroscopy and/or SEM-EDX) |

Handheld point XRF (P), visual examination (V) * Indicates where additional analyses are necessary for a firm identification (e.g. Raman spectroscopy and/or SEM-EDX) |

Macro-XRF (M), SEM-EDX (S), XRD (D), FCIR (false colour infrared), visual examination (V) * Indicates where additional analyses are necessary for a firm identification (e.g. Raman spectroscopy and/or SEM-EDX) |

| Skin tone | Lead white (M). Chrome orange (M, V)* is present throughout skin and is more concentrated on cheeks, middle of nose, and top of forehead. Ochre (M) is used to define structure of nose, jaw line and forehead | Lead white, zinc white, chrome yellow and/or chrome orange* concentrated along outlines of arms and hands. Smaller amounts of ochre in outlines of left hand and left shoulder | Lead white (M, P), zinc white* (M, P), chrome yellow orange and chrome orange (along contours of features) (M, P, FTIR, R), vermilion (rosy skin tones, mostly along contours of features) (M, P, R), iron-based earth pigment (shadow around proper right eye, along contours of features) (M, P), cadmium yellow* (back of neck and other contours of features) (M, P) | Zinc white* (M, P), lead white (M, P), chrome orange (along proper right contour of neck), vermilion (rosy skin tones, mostly along contours of features) (M, P), iron-based earth pigments (along contours of chin and neck) (M, P), cadmium yellow* (along contours of features) (M, P) | Zinc white, lead white, calcium, chrome-based pigment (P)* | Lead white, vermilion, ochre (co-present in small amount in the face and in higher quantity in the neck and for some shadow under the eyes, and in the eyebrows) and a chrome-based pigment |

| Red/pink | Red ochre (M, F, S, Mi), vermilion (M, P, V), chrome orange (M, V)* | Vermilion (lips) | Mars red (hair) (M, P, R), vermilion (lips, skin tones, hair, chair) (M, P, R) | Vermilion (lips, skin tones, hair, rectangular object) (M, P), chrome orange (hair, skin tones, rectangular object) (F) | Red iron-based pigment (hair, chair, sideboard), vermilion (lips) (P)* | Vermilion (M, D) |

| Brown | Ochre(s) (M), yellow-brown ochre confirmed from a sample scraping (M, F, S, Mi) (see ‘Yellow’ below) | Ochre/s, umber indicated by manganese co-present with iron (hair, armchair), chrome yellow and/or chrome orange* (hair only) | Iron-based earth pigments, including umber indicated by manganese co-present with iron (hair, skin tones, chair, rectangular object, brown background) (M, P) |

Iron-based earth pigments, including umber indicated by manganese co-present with iron (hair, skin tones, chair cushion, rectangular object) (M, P) |

Iron-based earth pigments* | Ochre/s, umber indicated by manganese co-present with iron (hair, hat, jumper) |

| White | Zinc white (M), lead white (M, R) | Lead white, zinc white | Lead white (M, P, F, R), zinc white* (M, P) |

Lead white (M, P, F, R), zinc white* (M, P) |

Lead white, zinc white* | Lead white (M, S) |

| Black | Bone black (M, F, S, Mi) | Calcium identified in black paint, likely present in a bone black* | Bone black* (rectangular object) (M, P) | Bone black* (outlines, grey background, rectangular object) (M, P) | N/A | Bone black (M, S) |

| Blue | N/A | Prussian blue (R). Blue background also contains relatively large amounts of zinc, likely present as zinc white | Cobalt blue* (outlines, grey background, eyes, rectangular object) (M, P), Prussian blue (dress) (R) | Ultramarine blue (outlines, grey background) (FTIR) | Deep blue iron-based pigment assumed to be Prussian blue (skirt) with small amount of chromium, traces of copper (P, V)*. Light blue of eyes: primarily zinc white with iron-based pigment likely present as Prussian blue (P, V), with sulphur, chlorine, aluminium and calcium also detected, possibly present as ultramarine (P)* | Cerulean blue (oxides of cobalt, aluminium and chromium), copper-based pigment (M) and possibly Prussian blue (FCIR)* |

| Yellow | Cadmium yellow (M, V), yellow ochre (M, F, S, Mi) | Chrome yellow, ochre | Chrome yellow-orange and/or chrome orange (hair, skin tones, chair, rectangular object, brown background) (M, P, FTIR, R), cadmium yellow* (hair, skin tones, rectangular object) (M, P), zinc yellow (dress, grey background) (M, P, R), cobalt yellow (hair, dress) (M, P, R) | Cadmium yellow* (hair, skin tones, rectangular object, chair cushion) (M, P) | Iron-based yellow earth pigment, chrome yellow, zinc yellow (P, V)* | Zinc yellow (S) |

| Other colours | In sample scrapings, gypsum (F, S) was found to be co-present with various pigments: red ochre, yellow ochre and bone black. Also in scrapings, calcium carbonate (S) was identified as co-present with yellow ochre and bone black | Copper and arsenic co-present in the left side of the background, and are likely present as emerald green* | Chromium associated with bluish-green paint, likely viridian* (grey background, dress) (M, P, V), calcium sulphate (M, P, F) co-present with lead white, barium co-present with cobalt blue*, chrome orange, and chrome yellow-orange (M, P), red lake* likely present on the painting (V) | Chromium associated with bluish-green paint in background and dress, likely viridian* (grey background, dress, proper left eye) (M, P, V), calcium sulphate (M, P, F) co-present with lead white, barium co-present with ultramarine blue and chrome orange (M, P), red lake* likely present on the painting (V) | Background is primarily zinc with calcium, chromium, iron, arsenic and copper, likely present as chrome yellow, viridian or emerald green (P, V)*, calcium found to be co-present with many pigments*, zinc white not detected in ground, but present in every pigmented area* | Copper and arsenic co-located in the left side of the background, and are likely present as emerald green (M) |

| Other analysis |

||||||

| Canvas weave |

Plain weave 12.2 horizontal (warp) and 14.8 vertical (weft) threads per centimetre |

Plain weave 13.2 horizontal (warp) and 11.5 vertical (weft) threads per centimetre |

Plain weave 19.4 horizontal (warp) and 16.8 vertical (weft) threads per centimetre |

Plain weave 20.3 horizontal (warp) and 19.7 vertical (weft) threads per centimetre |

Plain weave 22.1 horizontal (warp) and 22.8 vertical (weft) threads per centimetre |

Plain weave 23.6 horizontal (warp) and 21.9 vertical (weft) threads per centimetre |

| Paint medium | Oil (F). Small amounts of proteinaceous binder cannot be ruled out; absorption peak at ~1642 cm-1 suggests some possibility of small amounts of proteinaceous material (mixed tempera technique) but could also be due to carboxylates (degradation by-products) | Oil (V) | Oil (V) | Oil (V) | Oil (V) | Oil (V) |

| Ground preparation |

Bottom layer: barium sulphate (coarse particles, up to 50 μm in longest dimension) (R, S). Fine particles of barium sulphate and zinc sulphide, likely as lithopone (S). Quartz (S), unidentified particles composed largely of calcium and fluorine (S) Top layer: lead white (R, S) |

Bottom layer: lead white and barium white (R, S). Abundant angular quartz particles, and particles composed of barium, sulphur and zinc, possibly as lithopone (S) Top layer: lead white (R, S) |

Lead white (M, P, F) with small amount of barium-, zinc-, iron- and calcium- containing pigments and/or fillers (P) | Lead white (M, P) with small amount of barium-, zinc-, iron- and calcium- containing pigments and/or fillers (P) |

Lead white priming with calcium and small amount of barium (P) Possible second layer composed of lead/zinc (OR all colours mixed with zinc) (P)* |

Lead white (M, S) with some barium sulphate particles (S) |

Table 1

Summary of the results of pigment, media, ground preparation, varnish and canvas thread count analyses for all six portraits

Composition, pose and dress

The eleven smaller bust-length portraits of Hébuterne are mostly frontal or profile views. In some of these pictures, she wears the same clothing that appears in larger portraits, but they offer few clues as to the setting in which she posed. In all of the three-quarter-length portraits, Modigliani depicts Hébuterne sitting on a chair or a sofa. As is typical of his portraits, the backgrounds are mostly simple interiors without any outstanding design elements, featuring free and open brushwork.

The portraits of Hébuterne can be organised into subgroups based on the sitter’s appearance. The Metropolitan and both Barnes portraits show her wearing white gauzy dresses or chemises that suggest warm weather; even if the images show her in what was effectively undergarments, it seems unlikely that she could have sat in such a lightweight outfit in winter. In contrast, the Guggenheim and Troyes portraits depict Hébuterne in a thick yellow polo neck jumper, indicating that the sittings took place during the colder months.6

Fig.10

Amedeo Modigliani

Jeanne Hébuterne 1918

Oil on canvas

1010 x 657 mm

Norton Simon Art Foundation, Pasadena

C219

© Norton Simon Art Foundation

Fig.11

Amedeo Modigliani

Jeanne Hébuterne 1918

Oil on canvas

1295 x 914 mm

Private collection

C218

Public domain

Fig.12

Amedeo Modigliani

Jeanne Hébuterne, Seated in Profile with a Dark Dress c.1918

Oil on canvas

1000 x 650 mm

Private collection

C260

Public domain

A portrait from the Norton Simon Museum, Pasadena (C219; fig.10) and two privately owned works (C218 and C260; figs.11 and 12) feature Hébuterne in a red and black outfit with her hair tied back. The sitter’s pose in the Norton Simon portrait is mirrored by her pose in the front-facing privately owned work. Her profile-view pose in the other privately owned work, as well as her hairstyle, are nearly identical to those of the Barnes portrait. None of these three works points to a season or location, but the fashionable style of Hébuterne’s dress might indicate that they were made before or between pregnancies, where she was more likely to experiment with dress, as she had as a student.

In the profile-view portraits from the Barnes and the private collection (figs.4 and 12), Hébuterne is depicted against a pale blue and golden background, seated with her hands folded in her lap, in a red ladderback side chair that appears in at least three other portraits.7 Her dresses are a similar shape in both pictures, with slim A-line skirts and long, close-fitting sleeves, but the neckline of the black and red ensemble in the privately owned work sits higher on Hébuterne’s décolletage than does the Barnes’s white version.

There is no indication of season or location in the smaller paintings that focus on Hébuterne’s face and hair.8 In the Yale portrait from 1918, Hébuterne appears as a much younger girl, wearing a ribbon in her pulled-back hair, yet all of the paintings were made within the same short timeframe. Her girlish appearance may reflect the tenderness that Modigliani brought to these portraits.

In at least three, and possibly four, paintings included in this study, Hébuterne appears to be pregnant (figs.4, 6, 7 and possibly 5). This is not surprising given that, as mentioned, Hébuterne went through two pregnancies between April 1918 and January 1920. It is unclear whether she was expecting their first or second child at the time Modigliani made the portraits, but whether he painted them in Nice in 1918 or in Paris in 1919, they share the luminous and transparent quality of the portraits the artist produced in the last years of his life. With their elongated and curvilinear forms and glowing palette, these tender portraits of Hébuterne – Madonna-like, sitting on a throne – evoke works from the High Renaissance of late-fifteenth- and early sixteenth-century Italy.9 The radiance of Hébuterne’s flesh tones, the heightened sense of intimacy created by her domestic setting and informal apparel, and the minor compositional changes made to the contours of her figure reflect the changes Modigliani made to his working process as he captured his partner at these transitional moments of her life.

Backgrounds

Modigliani favoured vertically divided interior architectural backgrounds for his portraits, a conventional pictorial device rendered with casual, open brushwork. However, there are certain visual clues, such as wall colours and architectural details, that might help to identify specific locations or seasons and contribute to a plausible chronology. The Metropolitan and the Guggenheim portraits have similar backgrounds of blue and green ochre walls, which suggests a common location.10 The two Barnes portraits (figs.4 and 5) could have been painted in the same room, with backgrounds that are visually linked by the pale blue-grey area behind Hébuterne. These passages have similar horizontal and vertical markings that imitate the rectangular rails and panels of a wooden door, lightly traced into the paint with a narrow brush. Painted doors appear in the background of several other large-format portraits by Modigliani, such as Madame Hanka Zborowska Leaning on a Chair 1919 (Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia; C313), The Little Peasant c.1918 (Tate; C257) and Red-Haired Young Man/The Student 1919 (private collection; C301).

Divisions in the background also appear in the smaller portraits. In the Yale painting, a short stroke of brown above the centre of Hébuterne’s head divides the ochre background. Grey tones frame her profile, creating a sense of space between the sitter and the wall. In the Troyes portrait, the division is more subtle, present as a variation in tone between the left and the right sides of the canvas.

In the two Barnes portraits, a rectangular object is propped against the wall on the right of the picture. A thick, neatly painted border of pale beige paint surrounds a plane of broad, loosely applied vertical brushstrokes of thin brown and orange paints. This object could be interpreted in multiple ways: as the verso of a stretched canvas, with a pale wooden stretcher or strainer bars contrasting with the brownish linen; or as the upper corner of a painting leaning against the wall, with the recto facing outwards and the white-primed tacking margins angled towards the viewer. Alternatively, the pale border may represent a plain off-white frame. The same rectangular object appears in a similar position in Jeanne Hébuterne, Seated in Profile with a Dark Dress (fig.12).

Supports

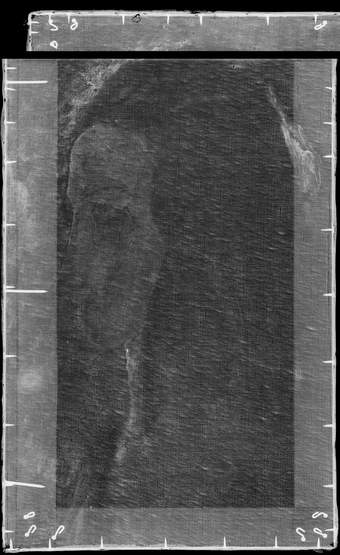

Fig.13a

Amedeo Modigliani

Portrait of Jeanne Hébuterne (Barnes Foundation), detail of the lower edge showing the narrow band of exposed ground at the centre

© 2022 Barnes Foundation

Fig.13b

Amedeo Modigliani

Jeanne Hébuterne with Yellow Sweater (Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum), detail of the lower edge showing exposed ground

Courtesy the Guggenheim Conservation Department

As is typical of his paintings, Modigliani painted most of his portraits of Hébuterne on standard-size marine and paysage canvases, used in a vertical orientation.11 He often painted with his canvas on an easel, which is evidenced by voids of paint at the lower front edge of the picture, where the lip of the easel shielded the canvas from the paint. The Guggenheim and the frontal Barnes portraits display narrow bands of exposed ground along their lower edges, suggesting that the canvases were painted at an easel fitted with a raised bottom ledge (figs.13a and b).12 In some cases, however, such as in the Yale portrait, this feature is missing, and evidence suggests the canvas may have been tacked directly onto a solid support while painting.

Thread count analysis carried out on the frontal Barnes portrait has revealed a match to the canvas weave of Modigliani’s Woman with Blue Eyes c.1918 in the Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris, suggesting that the two paintings were painted on material sourced from the same bolt.13 Thread count analysis also revealed that the canvas of the Guggenheim’s Jeanne Hébuterne with Yellow Sweater matches canvases Modigliani painted while staying in the South of France between April 1918 and May 1919, which may help to identify, if not the exact date, the location in which it was painted.14 This finding might lead us to speculate that the small portrait of Hébuterne from Troyes and the portrait at the Ohara Museum of Art in Kurashiki (C328), both of which show her wearing the same yellow jumper, could have been painted in the South of France. Temperatures in Nice are cooler in the winter, as would have been the case when Hébuterne was about to give birth to their daughter in November 1918.

Of the eleven bust-length paintings of Hébuterne, five are on paysage canvases – one on paysage no.8 and four on paysage no.10 – and one is on a figure no.15 canvas.15 The formats of the five remaining paintings, including the Yale and Troyes portraits, represent an interesting case study of the different supports used by Modigliani. Four bust portraits of Hébuterne from 1918 and 1919 have similar, non-standard dimensions: the Yale painting measures 46 by 28 centimetres, the Troyes picture measures 46 by 29 centimetres, and two paintings in private collections (C222 and C223) measure 46 by 29 and 44.8 by 27.5 centimetres respectively. These dimensions are more or less aligned with those of marine no.8 of the Lefranc system: 46 by 29.7 centimetres before 1905 and 46 by 30 thereafter.16 Despite all being listed in Ambrogio Ceroni’s 1970 catalogue as 46 by 29 centimetres, the small variations in the measurements of these works indicate that they may have been based on the dimensions of a marine 8 haut, but produced at a time when the artist did not have access to commercial stretchers or strainers.17

Fig.14

Amedeo Modigliani

Portrait of a Young Woman (Yale University Art Gallery), X-radiograph showing the flecked ground pattern and diagonal striations, as well as the unusual stretcher construction

Courtesy Yale University Art Gallery

The Yale painting is on an adapted wooden strainer, which was made by affixing a 1 centimetre wooden strip to the proper right side of a strainer with the proportions 46 by 27 centimetres (fig.14); strainer joints are fixed with three nails through half-lap joints. The portrait remains unlined and its current stretching dates to shortly after its completion, as the stretched canvas gently pulls towards the tacks along the perimeter – known as cusping – in a manner that corresponds to its current format. Records indicate that it has not been re-stretched since its acquisition in 1948. The unusual adapted strainer was likely the painting’s first secondary support, possibly assembled at the direction of the art dealer Léopold Zborowski to fit its nonstandard size. In addition to the current tacking, there is one additional incomplete set of tack holes, indicating that some holes were reused, or possibly that the painting was never fully attached to another strainer.

The Troyes portrait is lined and fixed onto a modern stretcher. Although the edges are concealed by lining tape, it appears on the X-radiograph that the painting area is slightly smaller than the lining dimensions. In both the Yale and the Troyes portrait, brushstrokes continue uninterrupted to the lower tacking edge. This, combined with the incomplete set of tacking holes evident on the Yale portrait, may suggest that the smaller paintings were created while tacked onto a flat support and later stretched, necessitating an adaptation to a pre-existing stretcher to match Modigliani’s estimated dimensions. Dark outlines that were applied in paint and pencil along the edges of the Yale composition also support this interpretation.

Evidence suggesting that these works were painted without an easel would also strengthen the hypothesis that Modigliani painted the Yale portrait, and possibly the other small paintings of Hébuterne (C222 and C223, in private collections), while sojourning in the South of France. As the artist moved between Nice and Cagnes-sur-Mer, working without an equipped studio, he may have had to improvise in terms of the auxiliary support. In addition to material similarities, these paintings share stylistic and iconographic elements, such as the hairstyle, black dress, elongated oval head, and the unique treatment of the eyes. This supports the idea that these small portraits were painted in the South of France, and probably at the same time, or at short intervals. Interestingly, in a letter that Modigliani sent from Nice to his dealer Léopold Zborowski in early 1919, he referred to a group of small portraits or ‘heads’ that he made of Hébuterne and was planning on sending to Paris: ‘I am waiting until a little head that I made of my wife is dry before sending you – with the ones you know about – four canvases’.18

Fig.15

Amedeo Modigliani

Jeanne Hébuterne (Metropolitan Museum of Art), detail showing the abraded black painted outlines along the top and right canvas edges

Courtesy Evan Read / Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Most of the portraits in this study show faintly painted lines along the edges of the compositions, mostly in black or ochre, possibly indicating a sizing device for painting without a stretcher or strainer. However, they could also signal a subtle visual framing device. These lines are now only partially visible, probably due to the lining and re-stretching of some of the canvases, not to mention their gradual erasure over time due to handling and cumulative abrasions from frames (fig.15).

Of the fifteen three-quarter-length portraits, thirteen are executed on marine and two on figure canvases. The artist used a wide range of marine formats: seven paintings are on marine 30; five are on marine 40 (including both of the Barnes paintings and the Guggenheim’s); and one is on marine 60. The Metropolitan’s canvas is one of only two figure 30 format canvases Modigliani used for his portraits of Hébuterne.19 It has remained unlined, but is probably not on its original stretcher.20

Ground preparations

The six paintings of Hébuterne examined in the present study are all executed on a white ground preparation. As described elsewhere, the portraits Modigliani painted in the South of France and after his return to Paris in 1919 were painted on commercially prepared, light-reflecting white grounds.21 Of the six paintings studied, the Troyes and the Barnes portraits have a ground with a single layer and the portraits from Yale, the Metropolitan and probably that from the Guggenheim have two layers in the ground (see Table 1).22 All have been commercially prepared, with lead white as a major component of at least one layer. Nevertheless, the precise composition of the ground differs from one painting to another, suggesting that Modigliani bought prepared canvas from different suppliers.

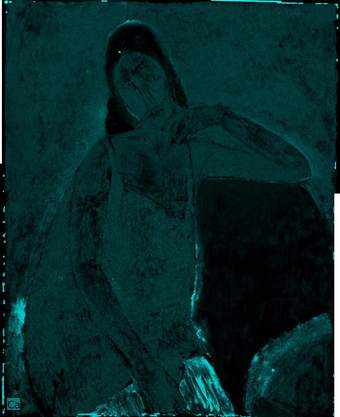

Fig.16

Amedeo Modigliani

Jeanne Hébuterne (Metropolitan Museum of Art), X-radiograph

Courtesy Evan Read / Metropolitan Museum of Art

X-radiography reveals that the Metropolitan painting’s ground preparation shares a unique, fine, diagonally flecked radio-opaque pattern with the Yale portrait. This pattern indicates a similar structure and ground application method; the diagonal striations are likely due to the differences in composition of the upper and lower ground layers (figs.14 and 16).23 Colour merchants carry prepared canvases from manufacturers who use distinct ground compositions, structures and application techniques. Such idiosyncratic ground application could therefore be traced to a single colour merchant, potentially placing the artist in the same location for both paintings, most likely the South of France. More research and analyses of Modigliani’s paintings remains to be carried out in order to find further examples of such prepared canvases, which could help to establish a plausible chronology.

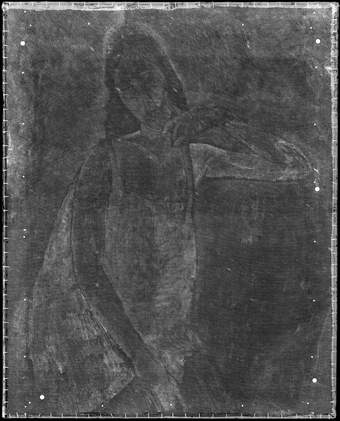

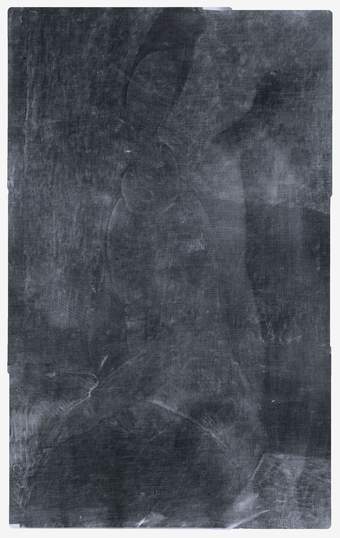

Fig.17a

Amedeo Modigliani

Portrait of Jeanne Hébuterne (Musée d’art Moderne de Troyes), X-radiograph

© C2RMF / Jean-Louis Bellec

Fig.17b

Amedeo Modigliani

Portrait of Jeanne Hébuterne (Musée d’art Moderne de Troyes), zinc distribution map

© C2RMF / Anaïs Genty-Vincent

Fig.17c

Amedeo Modigliani

Portrait of Jeanne Hébuterne (Musée d’art Moderne de Troyes), infrared reflectogram

© C2RMF / Jean-Louis Bellec

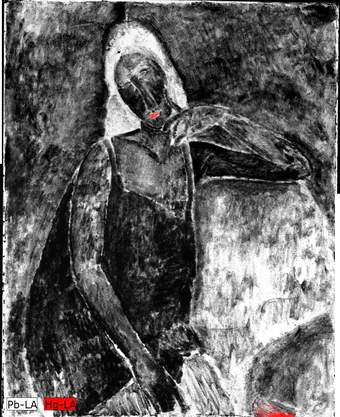

The portrait from Troyes has been painted on top of a previous painting that acts in some areas of the painting as a coloured ‘ground layer’. Brushstrokes that do not correspond to the finished portrait are discernible in the X-radiograph (fig.17a), and a triangular shape is visible on the zinc distribution map (fig.17b) and in the infrared reflectography image (fig.17c).24

Underdrawing

In all but one of the paintings included in the current study – the exception being the Troyes portrait – Modigliani sketched some of Hébuterne’s features directly on the ground layer before applying the paint. The underdrawings, which are made using a carbon-based black material, are easily discernible using infrared reflectography (IRR).

Fig.18

Amedeo Modigliani

Jeanne Hébuterne (Metropolitan Museum of Art), infrared reflectogram

Courtesy Evan Read / Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Fig.19

Amedeo Modigliani

Jeanne Hébuterne (Metropolitan Museum of Art), detail of the drawing outlines around the mouth and chin showing through the paint

Courtesy Evan Read / Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Fig.20

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres

Portrait of Madame Moitessier 1856

Oil on canvas

1200 x 921 mm

National Gallery, London

Close examination of the Metropolitan portrait shows Modigliani’s fluid drafting process, which remains partially visible through the thin paint. IRR reveals long and assured graphite drawing lines, indicative of the artist’s familiarity with his model (fig.18).25 Modigliani drew the final position of Hébuterne’s face fairly directly, without repeating the lines. The IRR image reveals that her nose was originally further to the left, and her face was lower on the canvas; lines indicating the lower original position of the chin and mouth remain clearly legible through the thin paint layer of the finished portrait (fig.19). Modigliani also made a slight adjustment to the sitter’s posture, repositioning her right arm twice. Fine drawing lines across her belly and lap remain visible in normal light, indicating the previous positions of the arm. The final placement of Hébuterne’s right hand, resting along the midline of her skirt, appears in many of the portraits. The distinctive position of her left hand, however, appears only in the Metropolitan portrait and was never altered. The placement of the hand supporting the face, and the position of the index finger in particular, recalls French neoclassical painter Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’s portrait of Madame Moitessier from 1856 (fig.20).26 In contrast to Ingres’s naturalistic depiction, however, Hébuterne’s hand appears rubbery and schematic, more reminiscent of the mannered drawing style of Modigliani’s contemporary, Henri Matisse.27 Once his drawing was set, Modigliani applied dilute black paint over the drawn outlines to settle certain features of the main contours; this effect is visible through the thin paint layer of the finished painting.

Fig.21

Amedeo Modigliani

Jeanne Hébuterne with Yellow Sweater (Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum), infrared reflectogram

Courtesy the Guggenheim Conservation Department

By contrast, little drawing shows through the paint in the Guggenheim portrait, except for small traces of fine pencil visible at the borders of forms, where thin slivers of the ground remain exposed, a characteristic often observed in Modigliani’s portraits. The IRR image reveals fine, confident lines that define the forms of the face, neck, jumper and hands (fig.21). With swift strokes of graphite, Modigliani sketched the portrait, delineating the contours of the figure, the bulky collar of the wool jumper, the sleeves and the hands. The only changes made to the composition were that Hébuterne’s chin was shortened and the proper right jawline was shifted to the left. The infrared image indicates that Modigliani smudged these lines to create shadow below the chin and around the eyes and hairline. Some fine graphite lines suggest forms below the breasts, perhaps to emphasise Hébuterne’s pregnancy.

As in the Metropolitan portrait, thin black, brown and grey painted lines, visible above and below the final image, follow the underdrawing and reinforce the linear quality of the Guggenheim portrait. Modigliani did not erase drawing lines that he revised – an approach also seen in some of his other compositions. This supports such accounts as that of the artist Léopold Survage, who described how the artist ‘worked rapidly, since his work was preceded by profound reflection’.28

Fig.22

Amedeo Modigliani

Jeanne Hébuterne (Barnes Foundation), infrared reflectogram

© 2022 Barnes Foundation

Graphite underdrawing is present in both Barnes paintings, but the method of application differs between the two. In the frontal portrait, the graphite markings are evident in the IRR image (fig.22) and just visible in normal light using a microscope, where they appear in small areas of exposed ground at the edges of the painted lines. The drawing is minimal, fluid and assured, mapping out the curves of the figure, the seams and folds of the sitter’s dress and the fine details of her facial features. The painted outlines follow the underlying graphite drawing quite closely, with some minor revisions around the upper curve of the hair and the jawline. Infrared imaging shows a few disconnected curved strokes that follow the horizontal curve of the sitter’s lap. It seems that the artist abandoned these initial markings – probably made to define the proportions of her figure – in order to further elongate the torso.

Fig.23a

Amedeo Modigliani

Portrait of Jeanne Hébuterne (Barnes Foundation), infrared reflectogram

© 2022 Barnes Foundation

Fig.23b

Amedeo Modigliani

Portrait of Jeanne Hébuterne (Barnes Foundation), detail of the hands in visible light

© 2022 Barnes Foundation

Fig.23c

Amedeo Modigliani

Portrait of Jeanne Hébuterne (Barnes Foundation), infrared reflectogram detail of the hands

© 2022 Barnes Foundation

The graphite drawing in the Barnes profile portrait is more extensive, and some lines are visible to the naked eye in the finished portrait. Decisive and sinuous contours are embellished with short, sharp, sketchy lines to define planes and angles in the flesh, a technique Modigliani often uses in his underdrawing. This is particularly well illustrated in the clasped hands (figs.23a, b and c), with the IRR image showing the geometric drawing in comparison to the rounded forms of the final painting. Modigliani traced the lines that describe Hébuterne’s hands with dilute blue paint, leaving graphite markings visible through the translucent flesh paint. This could have helped to guide the placement of deeper pink and golden brushstrokes, adding tonal depth and volume to the knuckles and fingertips. Revisions made to the composition in the drawing process are evident. Exploratory strokes define and adjust the position of the sitter’s hairline and jawline, the soft swell of her stomach and the wide neckline of her dress. Modigliani re-drew the outlines of her arms several times to establish the correct perspective. While painting, he continued to rework the torso. This is revealed by disturbances in the paint around the chest and stomach. The paint here is darker and cooler in tone than in the background, built up and scraped back, exposing traces of the bright white underlayer between the pronounced brushmarks.

Fig.24

Amedeo Modigliani

Portrait of a Young Woman (Yale University Art Gallery), infrared reflectogram

Courtesy Yale University Art Gallery

Modigliani used a surprising range of drawing styles in the smaller Yale portrait, which are revealed in infrared imaging (fig.24). He began his composition with a dry black medium, likely charcoal. Although the lines appear fluid in the finished work, in certain areas Modigliani used the same short, sharp, sketchy lines that are visible in the Barnes profile portrait. These straight lines, visible in the IRR image in the curves of the sitter’s nose and chin, suggest the artist was searching for a form or making changes to his initial conception of the portrait. The outline of the hair, which the infrared image reveals was originally slightly lower on the head, is more assured, drawn in long, curving strokes. He reinforced some of these drawn lines with black paint and returned to the black line often during the painting process to redefine and reinforce forms, as evidenced by the appearance of the lines both above and below several paint layers.

Painting technique

Fig.25

Amedeo Modigliani

Portrait of Jeanne Hébuterne (Musée d’art Moderne de Troyes) photographed in raking light from the left

© C2RMF / Gérald Parisse

Like most paintings Modigliani made during the last two years of his life, the portraits of Hébuterne included in this study are painted thinly and with low impasto. A notable exception is the Troyes portrait, which is executed with a high-bodied paint resulting in thick impasto brushstrokes, especially in the hair. Raking light photography highlights the exceptional texture of the painting (fig.25). In contrast, the artist painted the flesh tones of the face and of the neck with smoother brushstrokes.

Fig.26

Amedeo Modigliani

Jeanne Hébuterne (Metropolitan Museum of Art), detail of painted outlines

Courtesy Evan Read / Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Fig.27a

Amedeo Modigliani

Jeanne Hébuterne (Metropolitan Museum of Art), detail of the hairline showing black hatching

Courtesy Evan Read / Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Fig.27b

Amedeo Modigliani

Jeanne Hébuterne with Yellow Sweater (Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum), detail of the hairline showing black hatching

Courtesy the Guggenheim Conservation Department

In the Metropolitan portrait, the paint is thinly applied, enabling the dilute black paint with which Modigliani delineated key compositional features to show through the final layer. Under close examination, these lines appear pale grey and watery due to the sparse distribution of black pigment particles in the dilute paint, and because the white ground partly shows through. Modigliani sometimes lightly covered these outlines, so they appear as shadows in the flesh tones, as illustrated in the right eyebrow (fig.26). He later painted black outlines with a fine brush to outline features such as eyelids, eyebrows and the nose, and to reinforce pre-existing contours. This practice has been observed in many of the works studied in the wider research project of which this is a part.29 The small black hatching strokes present at the top of Hébuterne’s forehead, possibly defining a widow’s peak, are identical in both the Metropolitan and the Guggenheim portraits (figs.27a and b).

Fig.28

Amedeo Modigliani

Jeanne Hébuterne (Metropolitan Museum of Art), transmitted light photograph

Courtesy Evan Read / Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Like many of Modigliani’s late works, the Metropolitan portrait is quickly and freely executed. A transmitted light photograph reveals how thinly the picture was painted, and how much of the white ground is exposed throughout the composition (fig.28). It also emphasises the variety of Modigliani’s brushwork, from the finely blended paint application of the flesh tones to the open and free brushwork used for the clothing and for elements of the background.

Fig.29a

Amedeo Modigliani

Jeanne Hébuterne (Metropolitan Museum of Art), detail of the face in raking light

Courtesy Evan Read / Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Fig.29b

Amedeo Modigliani

Jeanne Hébuterne with Yellow Sweater (Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum), detail of the face in normal light

Courtesy the Guggenheim Conservation Department

Fig.29c

Amedeo Modigliani

Jeanne Hébuterne (Barnes Foundation), detail of the face in normal light

© 2022 Barnes Foundation

Fig.29d

Amedeo Modigliani

Portrait of Jeanne Hébuterne (Barnes Foundation), detail of the face in normal light

© 2022 Barnes Foundation

Fig.30

Amedeo Modigliani

Jeanne Hébuterne (Metropolitan Museum of Art), detail of the face in raking light showing the texturing from blotting on the right cheek

Courtesy Evan Read / Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The faces of the Metropolitan, Guggenheim and both Barnes paintings (figs.29a–d) are painted to a very smooth finish – delicately blended, with fine multidirectional brushstrokes. In each work, the modelling of the face, chest, arms and hair is characteristic of a classically trained artist, with subtle highlights and shadows and using the white ground to great effect. Modigliani traced the features in fluid outlines before filling them in with flesh tones, often leaving areas of the ground exposed along those lines. In the Metropolitan painting, a texture resembling a fabric weave pattern is visible on Hébuterne’s right cheek and on her left hand (fig.30), which suggests the paint has been blotted using a painting rag or paper, possibly to blend the pigments smoothly.30 The process results in a discreet quilting effect, which has not been observed in the other works included in this study. In at least one other work, the Metropolitan Reclining Nude, we have observed how Modigliani used a piece of cloth, or a paint rag, to polish or buff some of the flesh tones, rubbing the paint in a circular motion that has left visible striation patterns and fibre inclusions in the upper paint layer.31 This effect, while very distinct from the soft texture imprinted on Hébuterne’s face, suggests that the artist sometimes treated paint as a three-dimensional medium.

In the Guggenheim portrait, small directional strokes in the face and hair of the figure contrast with the swift application of paint that describes the sitter’s clothes and the background. In these areas, the artist used daubing and splayed brush, circular and zig-zag strokes with wider stiff bristle brushes that reveal the ground below. There are areas of ground visible at the edges of the eyes and mouth, which were left in reserve to be painted after blocking in the flesh tones. Each facial feature is ultimately defined by a dilute grey line, applied with a tiny brush. Hébuterne’s face and hair are emphasised by thin black outlines. Working flesh tones over dry paint along the red ochre hairline, Modigliani lengthened the sitter’s forehead and added a widow’s peak, accentuating it with fine black strokes. Hébuterne’s yellow jumper is painted with short strokes and low impasto to create the texture of wool. The artist mixed white pigment with yellow ochre to create the jumper’s fuzzy quality, with areas of ground visible through the bristled pattern. Parallel diagonal strokes define Hébuterne’s Prussian blue skirt, following the direction of her thighs. A final thin black line completes the jumper, while a thin brown line traces the outline of her crossed hands resting on her lap.

The face of the Yale portrait is modelled with a slightly more textural surface than the faces of the Metropolitan and Barnes works. Modigliani used a bristle brush and directional strokes to reinforce the planes and contours of the face rather than meticulously blending to a smooth finish. This low, barely perceptible impasto subtly reinforces the dimensionality of the sitter’s face. It is most noticeable in the areas of shadow that run down the left side of her nose to her cheek and below the chin. Elsewhere, daubs of paint emphasise the fleshy areas of Hébuterne’s face, such as in the pink skin above her left nostril and below her left brow. The ground is left visible through translucent, thinly painted areas such as the chin and upper cheek as well as around the black outlines. Contours are reinforced with black lines, which the artist applied wet-in-wet and blended with the surrounding colours to create shadow. Elsewhere, such as at the forehead and the top of the head, he painted black outlines onto the dry surface to define forms. He also applied daubs of brown paint at the top of the head, softening the division between the sitter’s hair and the background.

Modigliani illustrated the texture of Hébuterne’s hair by varying his brushwork and paint consistency. In general, he used a much looser hand and larger brushes for the hair than for the face. In the Yale portrait, the translucent brown paint that dominates the hair is applied with daubs and quick turns of the brush in repeated, calligraphic strokes. While the hair was defined almost entirely by red ochre paint dryly applied, a series of strokes near the sitter’s temple and neck comprise discrete layers of ochre highlights, with cadmium yellow to warm the tone. The hair that is tied back in a ribbon is made of black strokes, applied wet-in-wet, alternating with highlights of the same brown pigment lightened and made more opaque with the addition of zinc white. The thickest impasto of the painting is found in the white ribbon.

In the Metropolitan and the two Barnes paintings, Hébuterne’s dark red tresses are painted with more texture than her face, with tightly dabbed paint applied with a small rounded brush. In contrast, her clothing and the background are loosely painted, seemingly unfinished, showing casual open brushstrokes applied with medium-size rounded bristle brushes. In the Metropolitan portrait, the sitter’s right arm rests on an ochre support. It is possible that this is the same yellow jumper worn by Hébuterne in other portraits included in this study, perhaps here casually draped over the sofa. In both Barnes paintings, Hébuterne’s torso is the most highly worked area, with brushwork that dried quickly enough to retain crisp peaks and furrows. The variegated texture juxtaposes strokes of smooth, buttery paint with passages of gritty low impasto and a scraped-back, intentionally disturbed appearance. In both of the Barnes paintings, the loose greyish-blue brushwork of Hébuterne’s thighs is daubed and dragged, becoming increasingly sparse as it approaches the lower edge of the canvas and exposes the white underlayer.

Fig.31

Amedeo Modigliani

Portrait of Jeanne Hébuterne (Barnes Foundation), infrared reflectogram detail of the face showing changes to the position of the eyes

© 2022 Barnes Foundation

The small size of some of Modigliani’s portraits is not the only feature that suggests heightened intimacy with the sitter among this group. Of the twenty-six paintings of Hébuterne included in Ceroni’s 1970 publication, only four delineate the irises and pupils. Three of these pictures are among the four canvases close to marine 8 in format: two in private collections (C222 and C223) and the Yale portrait. These three pictures are also the only paintings of Hébuterne to depict her with dark eyes, rather than the light blue colour that Modigliani more typically used. Light blue seems to have been more faithful to Hébuterne’s eye colour, which is clearly light in tone (see fig.1). The fourth painting that delineates her irises and pupils, also in a private collection (C330), depicts her with light blue eyes. This work is only slightly larger in format and also conveys a sense of intimacy, with its closely cropped portrait of Hébuterne seated on a bed.32 Interestingly, an infrared reflectogram of the Barnes profile portrait reveals lightly traced outlines of irises underneath the blank pale blue eyes of the final composition (fig.31).

Fig.32

Amedeo Modigliani

Portrait of Jeanne Hébuterne (Musée d’art Moderne de Troyes), detail of the eyes

© C2RMF / Gérald Parisse

Of the marine 8 portraits, only the Troyes picture diverges from the pattern. Here Modigliani depicts Hébuterne with the characteristic blue-grey almond-shaped eyes of so many of his sitters (fig.32). The eyes are executed with a medium-rich paint and outlined with a black line. The lower outline is made with paint that is less rich in pigment and more fluid than the upper contour, which is particularly visible in her proper left eye. This eye is more varied in tone and texture, with a subtle play of colour and paint texture. The artist partially blended blue and white paint to create a marbled effect and illuminated the eyes with small white highlights. The final addition, after the black outline, was a touch of thick green paint at the lower edge of the eye.

Fig.33

Amedeo Modigliani

Portrait of a Young Woman (Yale University Art Gallery), detail of the eyes

Public domain

Fig.34

Amedeo Modigliani

Portrait of a Young Woman (Yale University Art Gallery), elemental map showing iron, calcium and zinc distribution, indicating the use of zinc to create a highlight in the left eye

Institute for the Preservation of Cultural Heritage, Yale University

In the Yale picture, the treatment of each eye is quite different (fig.33). The sitter’s left eye is carefully constructed, seemingly from observation and with a dedication to verisimilitude. Infrared imaging reveals underdrawing of vector lines in a dry carbon-based medium that situate the eye within the sunken contour of the face (see fig.24). Modigliani then painted the upper and lower eyelids and the white of the eye, which is carefully defined with graduated shading. He achieved this fine detail without overworking the canvas and by leaving the white of the ground showing through under the iris. The iris and pupil appear to be undifferentiated, but closer inspection reveals them to comprise two distinct, almost black, hues – the pupil is painted in a cool tone composed almost entirely of bone black, while the iris is warmed with the addition of iron ochre. A dab of zinc white creates a highlight in the pupil (fig.34). In contrast to the carefully laid contour and wet-in-wet blending of the left eye, the right eye is constructed with three short black strokes – one each for the upper and lower eyelids and one for the iris – against a thin background with some exposed ground. Above the right eye, a single stroke of paint defines the lid.

Palettes

Fig.35

Details of the lips from each of the Modigliani paintings included in this study. Clockwise from top left:

Jeanne Hébuterne (Metropolitan Museum of Art), Portrait of Jeanne Hébuterne (Barnes Foundation), Jeanne Hébuterne (Barnes Foundation), Portrait of a Young Woman (Yale University Art Gallery), Portrait of Jeanne Hébuterne (Musée d’art Moderne de Troyes), Jeanne Hébuterne with Yellow Sweater (Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum)

The Metropolitan portrait’s palette is modest and economical, mostly featuring ochres, lead white, zinc white, Prussian blue and chromium-based pigments, which Modigliani combined to achieve subtle modelling of skin tones.33 A stroke of vermilion red shaping the lips illuminates the sitter’s pale skin, a technique also seen in both Barnes paintings and the Yale portrait (see fig.35 and Table 1). With the exception of whites, the Guggenheim portrait shares a very similar palette and paint application technique with the Metropolitan canvas.

Fig.36

Amedeo Modigliani

Jeanne Hébuterne (Barnes Foundation), X-radiograph

© 2022 Barnes Foundation

The palettes used in the Barnes portraits feature similar complex pigment mixtures, with tonal variations of a few key hues used to block in passages of colour in the backgrounds, dress, flesh tones and hair.34 The X-radiograph of the frontal portrait reveals that reserves were left during the painting process for the warm-toned areas: Hébuterne’s red lips and hair and the orange interior of the rectangular object propped at the lower right of the background (fig.36).35

Fig.37

Amedeo Modigliani

Jeanne Hébuterne (Metropolitan Museum of Art), combination of MA-XRF distribution maps of lead (white) and mercury (red), the latter showing the vermilion pigment used in the lips and elsewhere in the composition

Silvia A. Centeno / Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Modigliani used a similar limited palette in the Yale portrait, using ochres, zinc white and lead white with the notable addition of chrome orange, which is also seen in the Barnes profile portrait and possibly in the Metropolitan portrait. The painting was executed primarily wet-in-wet, allowing for blending throughout the painting process. Technical analysis reveals that highlights, shading and a layer of flesh paint made from chromium-based pigments were applied on top of a base layer primarily composed of chrome orange and lead white.36 Modigliani used a thin stroke of vermilion to lay out the position of the lips with an initial outline (fig.37). He then used a foundation of chrome orange to create the overall shape of the lips before using just three brushstrokes to create accents of colour.

Vermilion is used in the flesh tones of the Troyes portrait and not only in the lips.37 The skin tones comprise vermilion mixed with lead white, ochre and a chromium-based pigment (chrome yellow or chrome orange), although more vermilion is present in the face than in the neck. It is interesting that although the eyebrows are not easily discernible on the painting, they are made with a high concentration of ochre and thus highly visible in the iron distribution map obtained by macro X-ray fluorescence. Hébuterne’s yellow jumper and hair are painted with lead white, ochre and/or umber (presence of manganese) and a chrome-based pigment identified on the cross-section as zinc yellow, a zinc chromate. The black outlines are made with bone black (see Table 1).

Changes

Fig.38a

Amedeo Modigliani

Portrait of a Young Woman (Yale University Art Gallery), infrared reflectogram detail showing changes to the turn of the face

Courtesy Yale University Art Gallery

Fig.38b

Amedeo Modigliani

Portrait of a Young Woman (Yale University Art Gallery), X-radiograph detail showing changes to the turn of the face

Courtesy Yale University Art Gallery

It appears that Modigliani altered the angle of the head in the Yale portrait during the painting process. This is indicated under normal viewing conditions by the brow that extends beyond the previously laid outline of the forehead, which was originally in full profile view. The infrared image shows evidence of an earlier outline in the bridge of the nose, made in short, sketchy lines, which is more curved towards the bridge than in the final image (fig.38a). This earlier profile is also marked by a more radio-opaque outline visible in the X-radiograph (fig.38b). The artist also modified the sitter’s hairline, pushing it back towards the right side of the image. This adjustment explains the very different approach taken to the construction of the right and left eyes, indicating that Modigliani’s decision to change the profile angle occurred after he had already started applying paint to canvas, perhaps even after having finished Hébuterne’s left eye.

Fig.39

Amedeo Modigliani

Jeanne Hébuterne (Metropolitan Museum of Art), MA-XRF calcium distribution map showing editing strokes of black-blue calcium-containing paint along both sides of the sitter’s blouse

Silvia A. Centeno / Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Fig.40

Amedeo Modigliani

Jeanne Hébuterne (Barnes Foundation), infrared reflectogram detail showing adjustments made to the belly

© 2022 Barnes Foundation

The Metropolitan picture and both of the Barnes portraits show evidence of alterations made to the shape of Hébuterne’s pregnant body. In the Metropolitan portrait Modigliani originally depicted her as more prominently pregnant, as is visible in the calcium distribution map (fig.39). He gently reduced her belly by painting over the left and right sides of her white blouse with dilute black brushstrokes, which appear as a soft bluish shadow on top of the dry white paint. Modigliani made similar adjustments to the Barnes portraits, in which the initial lines defining the curve of the sitter’s belly were partially painted over with opaque grey-blue paint (fig.40).

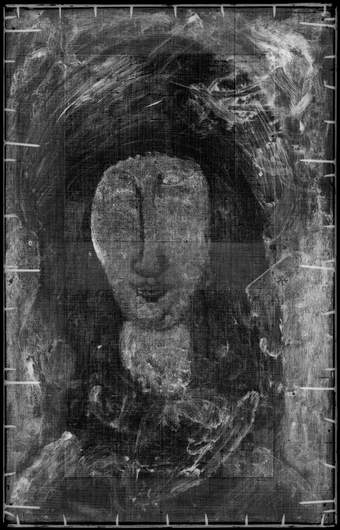

Fig.41

Amedeo Modigliani

Jeanne Hébuterne with Yellow Sweater (Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum), X-radiograph

Courtesy the Guggenheim Conservation Department

The Guggenheim X-radiograph indicates a somewhat perplexing change to the figure. To the proper left of the sitter there are two shapes that echo the profile of the body, suggesting that Hébuterne was moved to the left in the composition or reduced in size (fig.41). A curved shape towards the top of the image seems to suggest that Hébuterne’s head was once tilted to the left. However, there is no sign of these revisions through the very thin paint of the finished portrait, and no indication of these alterations in the infrared image. One explanation for this could be that changes were obliterated by the application of a zinc-containing paint, or alternatively that the way the ground was applied produced a pattern that reads as a figure in the X-radiograph.

Conclusion

This technical study of six of the twenty-six portraits Modigliani painted of Jeanne Hébuterne between 1918 and 1919 offers insights into the painter’s practice during the last years of his life. While the chronology of the Hébuterne portraits can be somewhat elusive due to the relatively short period during which they were painted, technical analysis indicates that the portraits included in this study were possibly all painted in the South of France.

There are clear visual links between the two Barnes portraits and the Metropolitan portrait, in the clothing, the backgrounds and the way in which the artist reworked the contours of Hébuterne’s pregnant torso. Canvas thread count analysis has revealed direct matches of both thread counts and weave patterns between the Guggenheim’s Jeanne Hébuterne with Yellow Sweater and the frontal Barnes portrait, with additional matches to canvases Modigliani painted during his sojourns in Cagnes-sur-Mer and Nice.38 The small portrait in Troyes could well be connected to the Guggenheim painting, since Hébuterne is wearing the same yellow polo neck jumper in both paintings. Other technical information, such as the unique ground pattern seen in both the Yale and the Metropolitan portraits, would indicate that both paintings were executed in the same location. Their distinctive ground preparation suggests that the same colour merchant was used for the two pictures, and Modigliani’s letter to Zborowski, in which he mentions small ‘heads’, places him in the South of France.

The portraits studied here are representative of the artist’s work during his final years. Modigliani favoured commercially prepared marine canvases with white grounds, which resulted in luminous compositions. With the exception of the small portrait from Troyes, all the canvases he used in 1918–19 were new. Recent research into works from French public collections has shown that Modigliani regularly reused his canvases until 1917, before he was more consistently supplied with materials by Zborowski.39 Future research remains to be undertaken to establish whether works in private collections follow the same pattern.

Tenderness and intimacy emanate from all the portraits of Hébuterne, mostly conveyed by the rounding and enveloping lines with which the artist drew her changing body and the luminous paint he blended to model her face, which shifted over time from a young adolescent’s to that of a mother. The portraits display techniques that have been observed in other late works by Modigliani: fluid drawing, direct painting execution and – with the exception of the Troyes portrait – thin paint application with sophisticated modelling and blending. The subtle modelling of Hébuterne’s face and attention to her varying hairstyles stand in striking contrast to the casual and sketch-like application of paint used for her clothing and the backgrounds. Perhaps most poignant is the artist’s attention to the subtleties of his partner’s changing figure, from a youthful teenager to a pregnant woman and a young mother. While these portraits are well rooted in an art historical tradition of female portraiture, they uniquely convey the intimacy between artist and sitter.