In early 2000 I was installed as writer-in-residence for the Wordsworth Trust at Grasmere. An acute case of pathetic fallacy soon set in. I knew this because I’d begun talking to the landscape. My room afforded a view of a high crag called Silver How that, according to one previous incumbent, was a platinum blond in morning mist or moonlight, but really a bracken redhead; so it became a she, and I started calling her ‘Jean’, as in Harlow. I got a call from a local artist, Russell Mills, who told me about an interesting ruin over the other side of Silver How, and would I like to come and look?

It wasn’t the kind of Lake District ruin I’d imagined. Not an ivy-raddled, crumbling Gothic edifice meant to be found by a Picturesque-hunter and viewed over the shoulder through a Claude glass. And nor was it one of the region’s many sites of cultural pilgrimage, an established node of disgorgement on the tourist trail fed by the A591. Russell took me along a quiet back road outside the village of Elterwater, which we soon left to brush and snag our way down a woody, overgrown slope. And there it was. A shed.

Then the astonishment, as I was told how this was where the German artist Kurt Schwitters had literally ended up, in extremis, calling for help and dying at the beginning of 1948. This ‘shed’ was the remains of his unfinished Merz barn, the third of his Merzbau constructions. The main wall was removed – with great difficulty and much strengthening of bridges – to Newcastle in the 1960s, but Russell himself might have experienced the same thrill and incredulity when he was led to this site in 1983, to discover an interior rubble of dead leaves and vines, a broken typewriter, rusty tubes of oils, a pair of outsize brogues and a workbench. By the beginning of the new millennium, most of that had gone, and only a shell remained. But entering its mossy gloom was still a through-the-looking-glass moment: finding this fastness of European modernism hidden away at the damp epicentre of English Romanticism was like coming across the image of a semiconductor on a cave wall.

Schwitters. Everybody ‘did’ Schwitters at art school. Collage. Dada. Weimar Germany, Merz, the European avant-garde, the Nazi’s Degenerate Art show. He’s there in E.H. Gombrich’s The Story of Art, although when I go back and check, Gombrich admits in his postscript to being unaware when his book was first published that ‘an elderly German refugee, whose work would prove of greater influence on the subsequent years, was then still living in England in the Lake District’. It seems the later Schwitters had slipped off the map and out of the big art historical narrative, but this complicated, out-of-time man had lived in Britain for the last seven and a half years of his life.

By the time the Gestapo came calling in 1937, the Hanoverian Schwitters was a well-established artist, in Germany and far beyond. He operated on many fronts: as well as creating collage and assemblage, he was a designer and typographer, produced a journal, wrote and performed poetry. Never exactly clubbable – Berlin Dada wasn’t having any of it, with one member, Richard Huelsenbeck, calling him ‘the Caspar David Friedrich of the Dadaist revolution’ – he was nevertheless a huge absorber and an enthusiastic collaborator.

Photograph of Elterwater Merz Barn in 1953

Merz took its name from what a bank would now call its ‘literature’, a textual fragment of Kommerz und Privatbank, and as a practice and way of making things it refused to privilege materials and objects. Instead, Schwitters drew the things the world discarded, that lay in tatters about him, into his updraft, taking items out of circulation from hyperinflationary Weimar and into art. In his economy of means, the bus tickets, sweet wrappers, cloakroom stubs and newspaper fragments that form the surfaces of so much of his collage work could be swept up through his life and read, a little like the newspaper headlines in Citizen Kane, shuffling linguistically and typographically from German to Norwegian to English, as he roamed (or was driven) across Europe.

Having fled Norway, he arrived in Edinburgh on an icebreaker in June 1940, just at the point when the British government introduced internship for German and Austrian nationals. He was billeted briefly on York racecourse, warehoused in a wrecked and verminous cotton mill in Bury, before being sent to an internment camp on the Isle of Man. Internees were also being shipped overseas, and there was a chance Schwitters might have crossed the Atlantic that July, but the torpedoing of the Arandora Star, bound for Canada full of German and Italian passengers, changed all that. He was stuck.

At this point, you might imagine a frustrating interregnum, an artist cut off from the most nourishing and vital of sources: home, friends, fellow artists, routine, funding and the simple, practical business of materials and time. But Schwitters, however dislocated and depressed, kept working. He travelled with a blizzard of accumulated scraps. On the Isle of Man, he made sculpture out of leftover porridge. The camps included many exiled scholars and artists in their numbers, and schools sprang up. Schwitters painted many of his fellow detainees, traditional portraits on linoleum, which earned him money. ‘I am not ashamed of being able to do good portraits,’ he said. Working in many media and on many fronts also included straightforwardly figurative art. He was always a hustler, an improviser and an opportunist in the best and broadest sense.

Schwitters experienced Britain in certain extremes: bomb-damaged urban London and remote, rural Cumbria; the circumscribed world of the internee and the open spaces of the Lake District; wartime and peace; town and country. I wonder how much the art he made during this period of disconnection and drift sustained him. His noticing of lovely useless things and his gathering and building have always struck me as more instinctive than any developmental theory can credit, as if he made his work the way a house sparrow will construct its nest, utilising the dog hair, bus tickets and cobwebs it finds in the streets. Suggesting this risks depreciating the artist’s strategic reflection on his own work – and Schwitters’s art during this period did develop in new and interesting ways – but was he always simply making and remaking a home out of detritus?

One obvious answer is that his aesthetic always tended towards what Robert Frost called ‘a momentary stay against confusion’. An artist’s work always tells us something about the practical occasion of its making: inner psychic weather aside, we can infer a lot from its materials, its scale, its proximity to (and dependence on) a studio, press or foundry, its relative settled-ness. In one sense, Schwitters learned early on to use and value the materials closest to hand, and it served him well. After all the European lines of supply had been snicked and broken by war, Schwitters did well on rations.

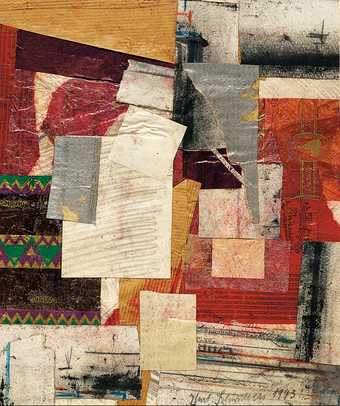

Kurt Schwitters

Untitled (Quality Street) 1942–3

Collage, 25 x 20.8 cm

Look at Untitled (Quality Street), a collage made in the middle of wartime London. It tells us something about the edges of that world, what it valued and what it threw away. In one way it’s as particular as a Mass Observation social survey, a documentation on litter, but it’s also alive to the simple childlike delight of looking at the world through a transparent sweet wrapper. And through the persistence of a British brand, it also feels strangely connected to us. This is our ephemera too, even though the work has now become a filter itself, as we look back from an era of glut and plenty into one of scarcity and austerity.

His years in London following internment were productive, but you sense his output wasn’t finding its audience. Schwitters the hustler asserted himself, and tried to make connections, though he never re-established the kind of networks he had enjoyed in Europe before the war. Out of sync as usual, he missed Mondrian, Walter Gropius and László Moholy-Nagy (although he did run into Moholy-Nagy’s ex-wife, purely by chance, in the PEN club). All had been in the capital, but were across the Atlantic by the time Schwitters arrived. He was still a German citizen. He did form contacts with other émigrés, did manage to exhibit his work and did read his poetry. But his standing and visibility had been injured by war. Perhaps his most important meeting in London was with a woman half his age called Edith Thomas, who worked as a telephonist in the Censor Office. Edith – or Wantee, as Schwitters called her – was to remain his companion for the reminder of his life.

And so to the Lake District, and Ambleside, where Schwitters and Wantee chose to move after the war in Europe ended. The ‘shed’ I stood in that day in Elterwater was his last attempt at Merzbau, a sculptural environment the viewer experienced from the inside as an enveloped participant. An earlier construction at Lysaker in Norway had been abandoned to the elements years earlier, and his first, built inside his former house in Hanover, was already bombed beyond repair by the time he arrived in Ambleside, although a combination of news travelling slowly and Schwitters being slow to accept this meant that he finally began work on his new Merz barn in the summer of 1947. (In a horrible irony, Russell told me how his father, who flew with RAF bombers during the war, was involved in the night raid on Hanover in October 1943 that flattened the Schwitters’s home.)

A strange rustication set in at Ambleside. The Lakes were a more remote place then than the Gortex inferno we find now. Schwitters and Wantee walked in the hills, and his habitual foraging now included a great deal of organic or mineral material. Two streams ran through the wood where the barn stood, and were used to mix decorator’s plaster. He’d continued to paint figuratively, landscapes and still-life studies as well as portraiture, often for money. Schwitters, exiled European modernist, one-time collaborator with Cubists, Dadaists and Constructivists, exhibited two collages at the Annual Lakeland Artists’ Exhibition at Grasmere in 1947.

Though we shouldn’t think of Schwitters as being entirely marooned. He was in touch with MoMA in New York, which wrote in May 1947 to inform him: ‘The grant for the Merzbau should finally come through within the next few days… Pretend it is a complete surprise.’ There is a photograph of him with the MoMA cheque conspicuously hanging out of his pocket. Nevertheless, time was running out. It’s impossible to ignore how ill Schwitters had become by this stage. Out of the two and a half years he spent in the Lake District, he must have been confined to bed for at least six months, and his catalogue of ailments is not for the faint-hearted.

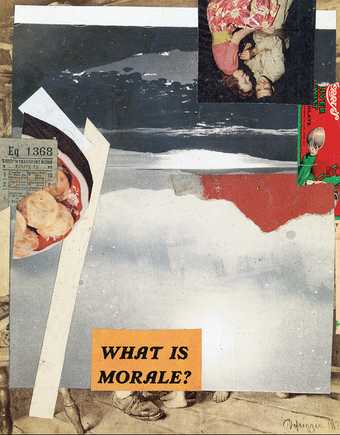

Kurt Schwitters

Untitled (The Doll) 1941–2

Paper and photograph on cardboard, 24.5 x 18.9 cm

The final months constructing the Merz barn, as summer turned to autumn, then a cold Cumbrian winter, seem baleful and heroic. Working by candlelight and warmed by an oil stove, with his health completely failing, site visits became less frequent. (It’s said Schwitters was a bus conductor’s nightmare: asked for his ticket on the journey over to Elterwater, he’d produce an avalanche of scrap papers from his pockets.) And then he disappeared in the dead of winter. On the day of his funeral in Ambleside – paid for by the remainder of the Merz barn grant from New York – the village policeman arrived to confirm that Kurt Schwitters was now indeed a British citizen.

There is something unsettled and unstable about Schwitters in his afterlife. His shrapnel peppers the second half of the last century, and still turns up today. Shortly after his death, the Independent Group formed in London, nebulous and looking towards Hollywood and Madison Avenue, but clearly occupying and expanding a space he made possible. There’s a whole history of his influence on British culture, the art school bands of the 1960s and 1970s, the look of Punk packaging. Once the audio technology had really caught up, you could say the 1980s were pure Schwitters, a sound collage. He was in the air.

But the harder I looked, the less I knew. He was a modernist, for sure, although perhaps the Berlin wing of Dada was right all along: he was also a Romantic, someone interested in making beautiful things, inclining towards and attending to the spiritual. In the English Lakes, in an empty space that contains many earlier absences – his body exhumed and re-interred in Germany, the reimagining of his Merzbau, destroyed by bombing and fire, itself removed on a low loader and reinstalled across the Pennines – I stood there among the twayblade, pines and rhododendrons and wondered how he’d managed the trick of being everywhere and nowhere.