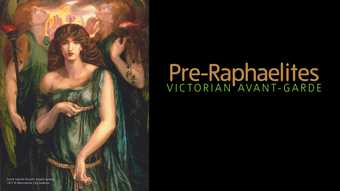

Richard Holloway on Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s Proserpine 1874

The old black-and-white Hollywood movies probably did it best. Gloria Grahame, as the gangster’s mistress in The Big Heat, captured the look perfectly; and so did Ingrid Bergman in Casablanca. It wasn’t exactly there in Marilyn Monroe’s performance in The Misfits, probably because she had already begun her descent into amphetamine hell, but it was certainly there in some of the stills taken during the troubled shoot of what turned out to be her last film. It is the look of tragic beauty, the look of the woman who knows she is cursed by her appeal to powerful men. This is very far, of course, from the look of the dumb blonde, the cat-like satisfaction of the trophy woman who is happy to be used as a bit of arm candy for a wealthy man: she understands the game and has her reward. No, what gives depth to tragic beauty is the obvious intelligence of the woman in the frame and her absolute awareness of the nature of her destiny in a world controlled by men. She knows that she cannot be herself; she is an object, a beautiful object. And she is haunted by the loss of herself, damned by her beauty, never to be cherished for herself alone.

For me, the perfect, most iconic expression of the look is found in this painting by Dante Gabriel Rossetti of Jane, the wife of William Morris, as Proserpine. When Morris married the working-class girl Jane Burden, one of the “stunners” of the Pre-Raphaelites, Bernard Shaw said she knew that being beautiful was “part of her household business”.

It was an unhappy marriage, made worse by Rossetti, who painted her obsessively. But, to be fair to the artist, he has created an honest picture. Look at Jane’s eyes and see the heaviness of the sorrow that was in her; the sorrow of the woman who knows she has been trapped forever by her own beauty.

Proserpine was presented by W Graham Robertson in 1940.

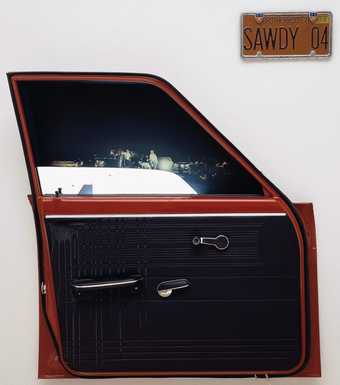

Edward Allington on Edward Kienholz’s Sawdy 1971

Edward Kienholz

Sawdy 1971 (detail)

© Tate

There is one thing I share with Ed Kienholz: cars. He traded them all his life, and he’s buried in one – his beloved 1940 Packard. Sawdy is a work made just before he met Nancy Reddin in 1972 and started their long productive collaboration. When I see a car part, such as this door, I see the whole vehicle. This is a really positive feeling. I think about putting it back where it belongs. I think about trading the door for parts I need for one of my rebuild projects. Then there’s the number plate. If you look at the top, it says Brotherhood. The window is open. It’s like we’re just cruising on by, but what’s happening out there? The scene is from Kienholz’s Five Car Stud 1969–72 and it’s something you just don’t want to see. White racists are castrating a black man. My father was a racist, and sadly I can recognise that feeling of being close to something completely inhuman and yet being powerless to change it. All I could do was leave – I had to drive on by, and I’m not proud of it. But that’s Ed Kienholz for you, and Nancy too: they are not going to let you forget all that stuff. This work is much more than a car door, a silkscreen and a number plate.

Sawdy was loaned by the American Fund for the Tate Gallery, courtesy of Melinda Shearer Maddock, in 2001

David Austen on Alberto Giacometti’s Hour of the Traces 1930

It is always smaller and more fragile than I remember. Its title is redolent of deep night, stained sheets and dragged bodies, while the cage-like structure is reminiscent of the scaffold and the guillotine, or a charred building. Above, attached by twisted bent wire to the roof beams like an early television aerial, are three white shapes: an upside down “L” or blind man’s cane, a crescent or shooting comet and a broken moon. These shapes could just as well be impaled body parts: a gaping head and a long skinny penis or tongue. This is a place of medieval torture or an ancient object from an Egyptian tomb. It is a grisly, cruel scene – none of the gaiety, humour and bird-like sounds that emanate from a Klee or Miró. “I work to please the dead” Giacometti said.

Dropped down into the body of the cage and held by a trembling wire is a small plaster heart. It is a pendulum in a Swiss clock, a beating heart from a Poe story, or a heart for a tin man. It makes me think of weight and gravity, the terrible lonely ache of love, passing moments and the “unbearable lightness of being”. I have a photograph I must have taken a very long time ago in Tate of the little plaster heart hanging by its wire. Now and then it surfaces to the top of a big pile of images I have in my studio. I always stop and look and think how something so simple can work so well, and it’s always going to be there.

Hour of the Traces was purchased with assistance from the Friends of the Tate Gallery in 1975, and is on view at Tate Modern until July 2005

Ben Faccini on Marcus Gheeraerts II’s Portrait of Captain Thomas Lee 1594

Marcus Gheeraerts II

Portrait of Captain Thomas Lee

(1594)

Tate

Why, Captain Thomas Lee, are your legs pale as slithers of moon, your thighs cold as marble? Your silken feet, unsullied by the stain of the peat soil beneath you, barely seem to touch the ground, suspended, weightless. The veins of your unblemished ankles and hairless shins stand rigid with a faint blue. Your elegant, manicured toes, accustomed to ceremonial shoes, point forward, noble in their slender proportions.

Are you a pilgrim, your ashen legs those of a contrite traveller stripped for penitence, your feet set to injure their way towards forgiveness? Are you a creature of mythology, half-courtier, half-statue, breaking from the thickness of the forest, harbinger of some calamity? Are you a returning warrior, wounded by unrequited love, your exposed limbs already those of a punished corpse, drained of blood, deathly in pallor, sculptural in stillness, pain turned to stone – a future effigy for your tomb?

Captain Thomas Lee’s aim in this painting, apparently, was to vaunt his credentials as a peace negotiator between the Crown in Ireland and the various local rebels a position he believed would be richly rewarded with status and lands. The painter, Marcus Gheeraerts II, depicts Lee’s connections to both camps: the bare legs are like those of an Irish foot soldier, the richly-woven costume is that of gentleman of high birth. Gheeraerts, with a disturbing degree of prophetic vision, also seems to discern the ambiguities of his subject’s dual ties. Lee, indeed, became ensnared in the labyrinth of Anglo-Irish politics and his links to an attempted coup d’état by his master, the Earl of Essex, meant that his ambitions came to an abrupt end.

Your feet, Captain Thomas Lee, barely seem to touch the ground, as if they were on the scaffold at Tyburn, where you were hanged for treachery on 13 February 1601.

Portrait of Captain Thomas Lee was purchased in 1980 and is part of BP British Art Displays at Tate Britain.