In Tate Liverpool

Democracies

Free- Artist

- Cildo Meireles born 1948

- Original title

- Interções em Circuitos Ideolõgicos: Projeto Coca-Cola

- Medium

- 3 glass bottles, 3 metal caps, liquid and adhesive labels with text

- Dimensions

- Object, each: 250 × 60 × 60 mm

- Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Presented by the artist 2006, accessioned 2007

- Reference

- T12328

Summary

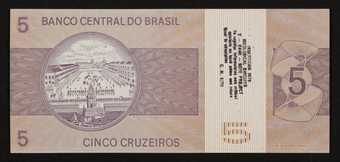

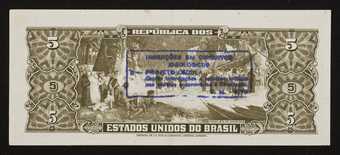

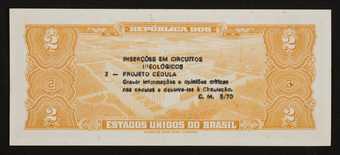

Meireles conceived his two Insertions into Ideological Circuits projects for an exhibition of conceptual art held at The Museum of Modern Art, New York in 1970 entitled Information. The Coca-Cola Project and the Cédula or Banknote Project (see Tate T12512-38) explore the notion of circulation and exchange of goods, wealth and information as manifestations of the dominant ideology. For the Coca-Cola Project Meireles removed Coca-Cola bottles from normal circulation and modified them by adding critical political statements, or instructions for turning the bottle into a Molotov cocktail, before returning them to the circuit of exchange. On the bottles, such messages as ‘Yankees Go Home’ are followed by the work’s title and the artist’s statement of purpose: ‘To register informations and critical opinions on bottles and return them to circulation’. The Coca-Cola bottle is an everyday object of mass circulation; in 1970 in Brazil it was a symbol of US imperialism and it has become, globally, a symbol of capitalist consumerism. As the bottle progressively empties of dark brown liquid, the statement printed in white letters on a transparent label adhering to its side becomes increasingly invisible, only to reappear when the bottle is refilled for recirculation. The Currency Project followed a similar structure, with texts containing information and critical messages being stamped onto banknotes that were then returned to circulation. In both projects, the messages are in a mixture of English and Portuguese. Meireles has commented:

The Insertions into Ideological Circuits arose out of the need to create a system for the circulation and exchange of information that did not depend on any kind of centralized control. This would be a form of language, a system essentially opposed to the media of press, radio and television – typical examples of media that actually reach an enormous audience, but in the circulation systems of which there is always a degree of control and channelling of the information inserted ... The way I conceived it, the Insertions would only exist to the extent that they ceased to be the work of just one person. The work only exists to the extent that other people participate in it. What also arises is the need for anonymity. By extension, the question of anonymity involves the question of ownership. When the object of art becomes a practice, it becomes something over which you can have no control or ownership.

(Quoted in Cameron, pp.110-12.)

In 1970, when Meireles produced the Insertions into Ideological Circuits projects, Brazil was undergoing the most oppressive period of its twenty-one year government by military dictatorship. At the time, the Insertions constituted a form of guerrilla tactics of political resistance in order to elude the strict state censorship enforced by the regime. Commentary stamped onto banknotes in the Banknote Project included references to a journalist who had died in police custody under suspicious circumstances and calls for proper, free elections. For Meireles, the texts on circulating bottles and banknotes ‘functioned as a kind of mobile grafitti’ (quoted in Cameron, p.13). The three bottles presented to Tate by the artist are relics or symbols of the work which, for Meireles, is only operating when the bottles are actually in circulation. Their display – standing in a line of three, one full, one half full and one empty – mimics their earliest appearance as a photograph that demonstrates the process of consumption through which the artist’s message disappears before returning to visibility when the bottle is refilled. The Coca-Cola Project has never been sold because the idea is that people may stick labels with messages on bottles and themselves send out views or commentary into wider circulation. In order to function, the work depends on a system of deposit, in which empty bottles are returned for recycling.

Meireles belongs to a generation of Brazilian artists who fuse conceptual thinking with a multisensorial approach that prioritises the body. Labelled Neo-Concretism, the movement was founded in the late 1950s by Lygia Clark (1920-88) and Lydia Pape (1929-2004) and extended in the 1960s to include Hélio Oiticica (1937-80). In his objects and installations, Meireles uses a range of strategies to engage the viewer as a participant in the work. The Insertions into Ideological Circuits projects go beyond the viewer in the gallery or museum, and extend to a wider public who may be unaware of their contact with art.

Further reading:

Open Systems: Rethinking Art c.1970, exhibition catalogue, Tate Modern, London 2005, reproduced fig.53, p.138 in colour.

Information, exhibition catalogue, Museum of Modern Art, New York 1970.

Dan Cameron, Paulo Herkenhoff and Gerardo Mosquera, Cildo Meireles, London 1999, pp.108-16, reproduced pp.108-9 and 111 in colour.

Elizabeth Manchester

September 2006

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Display caption

Meireles altered a series of Coca-Cola bottles, by printing slogans such as ‘Yankees go home’ or instructions for making Molotov cocktails on them. He put them back into circulation in what he described as an act of subversive ‘mobile graffiti’, enacted under Brazil’s military dictatorship. He saw the system of recycling empty bottles as a way of enabling a political message to circulate surreptitiously. He has compared the Coca-Cola bottles to ‘messages in bottles, flung into the sea by victims of shipwrecks’.

Gallery label, February 2016

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Explore

- emotions, concepts and ideas(16,416)

-

- formal qualities(12,454)

-

- defacement(257)

- politics and society(2,337)

-

- politics: Brazil(27)

- food and drink(980)

-

- drink, Coca-Cola(15)

- bottle(289)

- bomb(32)

- government and politics(3,355)

-

- political protest(361)

- commerce(93)

- corruption(117)

- inscriptions(6,664)

-

- instructions(36)

- printed text(1,138)

You might like

-

Cildo Meireles Insertions into Ideological Circuits 2: Banknote Project

1970 -

Cildo Meireles Insertions into Ideological Circuits 2: Banknote Project

1970 -

Cildo Meireles Insertions into Ideological Circuits 2: Banknote Project

1970 -

Cildo Meireles Insertions into Ideological Circuits 2: Banknote Project

1970 -

Cildo Meireles Insertions into Ideological Circuits 2: Banknote Project

1970 -

Cildo Meireles Insertions into Ideological Circuits 2: Banknote Project

1970 -

Cildo Meireles Insertions into Ideological Circuits 2: Banknote Project

1970 -

Cildo Meireles Insertions into Ideological Circuits 2: Banknote Project

1970 -

Cildo Meireles Insertions into Ideological Circuits 2: Banknote Project

1970 -

Cildo Meireles Insertions into Ideological Circuits 2: Banknote Project

1970 -

Cildo Meireles Insertions into Ideological Circuits 2: Banknote Project

1970 -

Cildo Meireles Insertions into Ideological Circuits 2: Banknote Project

1970 -

Cildo Meireles Insertions into Ideological Circuits 2: Banknote Project

1970 -

Cildo Meireles Insertions into Ideological Circuits 2: Banknote Project

1970 -

Cildo Meireles Insertions into Ideological Circuits 2: Banknote Project

1970