Not on display

- Artist

- Robert Mapplethorpe 1946–1989

- Medium

- Photograph, gelatin silver print on paper

- Dimensions

- Support: 577 × 481 mm

frame: 850 × 747 × 22 mm - Collection

- ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

- Acquisition

- ARTIST ROOMS Acquired jointly with the National Galleries of Scotland through The d'Offay Donation with assistance from the National Heritage Memorial Fund and the Art Fund 2008

- Reference

- AR00496

Summary

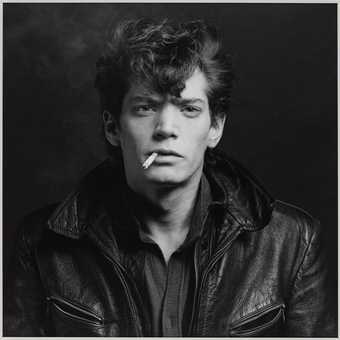

In this black and white self-portrait the photographer Robert Mapplethorpe’s head, which faces the camera directly, is positioned near the top right-hand corner of the image, while in the opposite corner his right hand grips a cane topped with a small human skull. Mapplethorpe wears black clothing that covers his torso, neck and arms, rendering them indistinguishable from the black background. This creates the illusion that his head is floating in empty space and serves to emphasise the stark paleness of his skin. The size of the hand in relation to the head indicates that it is closer to the camera, suggesting that Mapplethorpe was sitting down when this shot was taken, and that the cane and his right hand were positioned infront of him.

The portrait was taken in 1988 in New York, the year before Mapplethorpe died from an AIDS-related illness. Mapplethorpe had originally intended to take a photograph of his walking cane ornamented with a carved skull, however, while he was preparing the shoot he decided to put on a black turtleneck jumper and create this self-portrait instead. The shot was taken by the artist’s younger brother Edward, also a photographer, who was helped by Robert’s studio assistant Brian English. Edward Mapplethorpe began his career under the pseudonym Edward Maxey, assuming his mother’s maiden name, and the influence of his brother’s style is evident in his work. Patricia Morrisroe, Robert Mapplethorpe’s biographer, notes that Edward ‘intuitively’ understood what his brother was hoping to achieve in this image, and so focused the camera on the hand holding the skull cane, slightly blurring Mapplethorpe’s head (Morrisroe 1995, p.335).

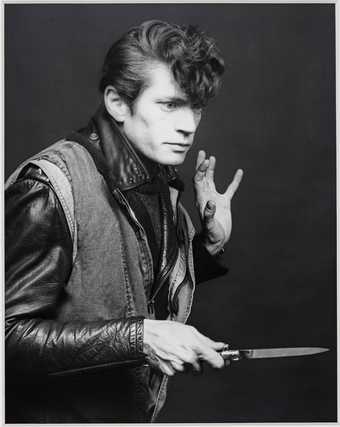

Portraiture is a significant genre in Mapplethorpe’s work. He photographed fellow artists, writers, singers, art collectors and curators, although his most photographed subject was himself. The critic Peter Conrad asserts that Mapplethorpe considered personality to be ‘serial’, a concept which he applied to his self-portraits (Conrad 1988, p.12). The artist depicted himself with devil horns, dressed as a woman, yielding a knife ready to thrust (Tate AR00227), and in the guise of a soldier or terrorist holding a rifle in front of an inverted pentagram, a symbol of the devil (Tate AR00226). It has been suggested that in this 1988 self-portrait the artist is no longer playing a role. Instead it is a more intimate portrayal compared to previous depictions of himself. Mapplethorpe appears gaunt and weathered as this portrait was taken just months before his death. The slight blurring of his head in relation to his hand gives the impression that he is gradually fading away.

Mapplethorpe produced increasingly macabre and morbid work at this time, exemplified by his photographs of human skulls (Tate AR00223). He considered the skull the purest sculptural image of all for its clean lines were undisturbed by flesh or hair (Morrisroe 1995, p.335).

Further reading

Peter Conrad, ‘Twelve Facets of Mapplethorpe’ in Mapplethorpe Portraits: Photographs by Robert Mapplethorpe 1975–87, exhibition catalogue, National Portrait Gallery, London 1988.

Patricia Morrisroe, Mapplethorpe. A Biography, London 1995, p.335.

Susan Mc Ateer

The University of Edinburgh

February 2013

The University of Edinburgh is a research partner of ARTIST ROOMS.

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Online caption

In this late photograph, Mapplethorpe is no longer playing a role, as he did in so many of his earlier self-portraits. It was taken a few months before he died from an AIDS-related illness in 1989. In it he faces straight ahead, as if he were looking death in the face. The skull-headed cane that he holds in his right hand reinforces this reading. Mapplethorpe is wearing black, so that his head floats free, disembodied, as if he were already half-way to death. Mapplethorpe even photographs his head very slightly out of focus (compared with his hand) to suggest his gradual fading away.

Explore

- emotions, concepts and ideas(16,416)

-

- formal qualities(12,454)

-

- photographic(4,673)

- clothing and personal items(5,879)

-

- cane / walking stick(118)

- hand(602)

- head / face(2,497)

- skull(90)

- self-portraits(888)

- arts and entertainment(7,210)

-

- photographer(255)

You might like

-

Robert Mapplethorpe Pictures / Self Portrait

1977 -

Robert Mapplethorpe Pictures / Self Portrait

1977 -

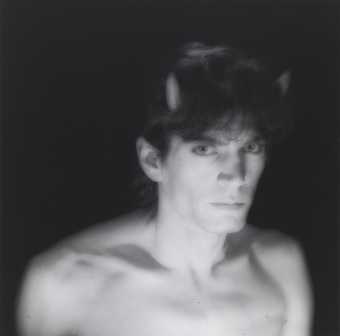

Robert Mapplethorpe Self Portrait

1980, printed 1999 -

Robert Mapplethorpe Self Portrait

1983, printed 2005 -

Robert Mapplethorpe Self Portrait

1985 -

Robert Mapplethorpe Self Portrait

1980, printed 1990 -

Robert Mapplethorpe Self Portrait

1988 -

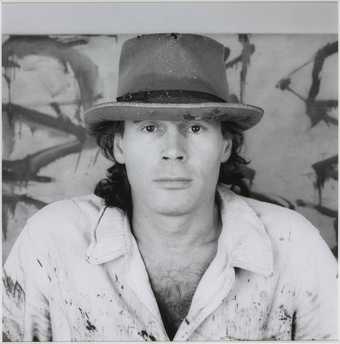

Robert Mapplethorpe Brice Marden

1986 -

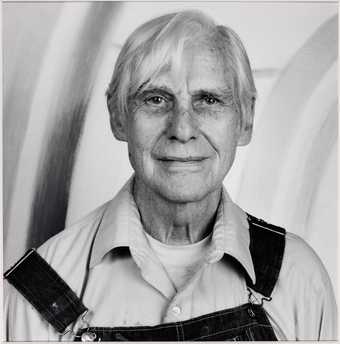

Robert Mapplethorpe Willem de Kooning

1986 -

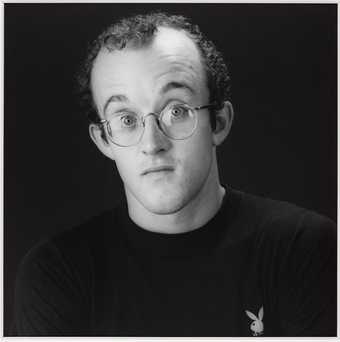

Robert Mapplethorpe Keith Haring

1984 -

Robert Mapplethorpe Self Portrait

1980 -

Robert Mapplethorpe Self Portrait

1983 -

Robert Mapplethorpe Self Portrait

1983 -

Robert Mapplethorpe Self Portrait

1981, printed 1992 -

Robert Mapplethorpe Self Portrait

1988