In Tate Modern

- Artist

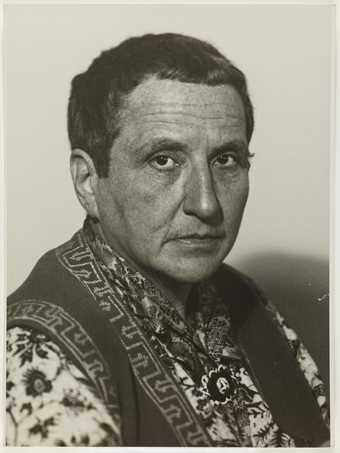

- Man Ray 1890–1976

- Medium

- Iron and nails

- Dimensions

- Object: 178 × 94 × 126 mm

- Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Presented by the Tate Collectors Forum 2002

- Reference

- T07883

Summary

Cadeau, 1921, editioned replica 1972, or ‘Gift’, is one of the famous icons of the surrealist movement. It consists of an everyday continental flat iron of the sort that had to be heated on a stove, transformed here into a non-functional, disturbing object by the addition of a single row of fourteen nails. The transformation of an item of ordinary domestic life into a strange, unnameable object with sadistic connotations exemplified the power of the object within dada and surrealism to escape the rule of logic and the conventional identification of words and objects. Man Ray once said, ‘There are objects that need names.

In his autobiography Man Ray recounted the story of the making of the original Cadeau. On the day of the opening of his first solo exhibition in Paris he had a drink with the composer Erik Satie and on leaving the café saw a hardware store. There with Satie’s help – Man Ray spoke only poor French at this point – he bought the iron, some glue and some nails, and went to the gallery where he made the object on the spot. He intended his friends to draw lots for the work, called ‘Cadeau’, but the piece was stolen during the course of the afternoon.

Arturo Schwarz, Man Ray’s dealer and author of a monograph on him, has written of this piece:

Gift is a typical product of Man Ray’s double-edged humour. Its sadistic implications need not be stressed. Its erotic aspect is revealed by Man Ray’s remark: ‘You can tear a dress to ribbons with it. I did it once, and asked a beautiful eighteen-year-old coloured girl to wear as it as she danced. Her body showed through as she moved around, it was like a bronze in movement. It was really beautiful.

Man Ray’s intentions, which might be seen as merely to deride the iron’s functions are much more subtle. Man Ray never destroys, he always modifies and enriches. In this case, he provides the flatiron with a new role, a role that we dimly guess, and the probably accounts for the object’s strange fascination. (Schwarz, p.208)

This example is one of approximately five trial pieces made by Man Ray in preparation for the edition of eleven, published by the Galleria Il Fauno, Turin, in 1972. All five were made using different irons dating from the interwar period, and the edition itself comprised different types of irons, as it proved difficult to find sufficient numbers of identical irons dating from the 1920s and 1930s. Man Ray’s studio assistant, Lucien Treillard, has said that the reason for the existence for these five trial pieces (each inscribed ‘essai’ and, in effect, unique pieces) was that it proved difficult to find an adhesive that held the nails: the five pieces were made as part of the process resolving this problem. The nails are made of copper and of the type used in making tapestries. The object has a layer of varnish, no doubt to protect the inscriptions in artist’s oil crayon. There was an earlier edition of 1963, published by the Galleria Il Fauno.

Despite Man Ray’s status as one of the pioneering figures of interwar art, his objects are not particularly widely known. This is largely due to his greater fame as a photographer; but it is also in part due to the complex history of many of his objects. A number of the earliest works were lost or accidentally destroyed (the same is true of many of the early classic objects by his friend Marcel Duchamp). Others are known primarily as photographs reproduced in surrealist magazines and their status as objects has been obscured by the celebrity of the photographic images. In fact, Man Ray sometimes made objects in order to photograph them, and then discarded them, or reused them in other ways. He also remade some works, thereby creating new originals, and when, in the 1960s and 1970s, there was a greater commercial interest in the objects, he, like Duchamp, arranged for some of his objects to be produced in editions.

In addition to Cadeau, Tate owns a number of other objects by Man Ray. They are L’Enigme d’Isidore Ducasse, 1920, remade 1972 (Tate T07957), New York, 1920, editioned replica 1973 (Tate T07882), Indestructible Object, 1922-3, remade 1933, editioned replica 1965 (Tate T07614), Emak Bakia, 1926, remade 1970 (Tate T07959), Ce qui manque à nous tous, 1927, editioned replica 1962 (Tate T07960), and The Lovers, 1933, editioned replica 1973 (Tate T07958).

Further Reading:

Man Ray: Objets de mon affection, Paris 1983, reproduced p.43

Arturo Schwarz, Man Ray: The Rigour of Imagination, London 1977, p.208

Jennifer Mundy

March 2003

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Display caption

By adding a row of nails, Man Ray transformed a household flat-iron into a new and potentially threatening object. The nails and burning metal suggest a violent eroticism at odds with the work’s title, the French word for ‘gift’. The original version, given to the composer Erik Satie, was lost but became well-known through Man Ray’s photograph of it. Although made at the height of Paris dada, Cadeau, like Man Ray’s other objects, anticipated the exposure of hidden desires found in subsequent surrealist objects.

Gallery label, January 2016

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Explore

- emotions, concepts and ideas(16,416)

-

- emotions and human qualities(5,345)

-

- desire(149)

- universal concepts(6,387)

- fetish(17)

- nail(22)

- inscriptions(6,664)

-

- French text(139)

You might like

-

Man Ray Gertrude Stein

c.1920–9 -

Man Ray Pisces

1938 -

Hans Bellmer The Doll

1936, reconstructed 1965 -

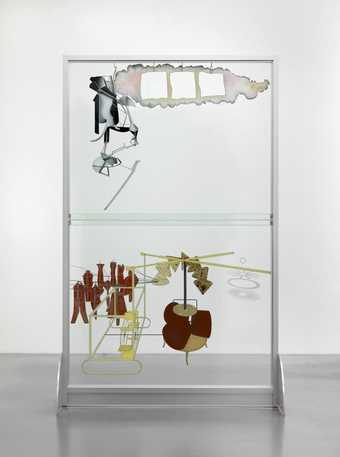

Marcel Duchamp The Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass)

1915–23, reconstruction by Richard Hamilton 1965–6, lower panel remade 1985 -

Jean Crotti Portrait of Edison

1920 -

Max Ernst Dadaville

c.1924 -

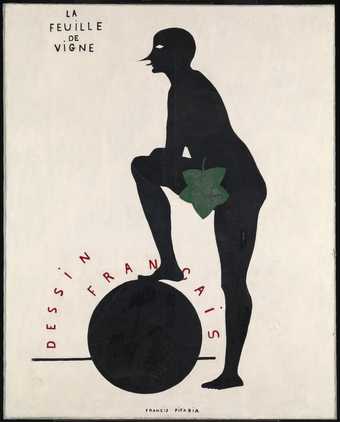

Francis Picabia The Fig-Leaf

1922 -

Man Ray Indestructible Object

1923, remade 1933, editioned replica 1965 -

Man Ray New York

1920, editioned replica 1973 -

Man Ray L’Enigme d’Isidore Ducasse

1920, remade 1972 -

Man Ray The Lovers

1933, editioned replica 1973 -

Man Ray Emak Bakia

1926, remade 1970 -

Man Ray Ce qui manque à nous tous

1927, editioned replica 1973 -

Francis Picabia Otaïti

1930 -

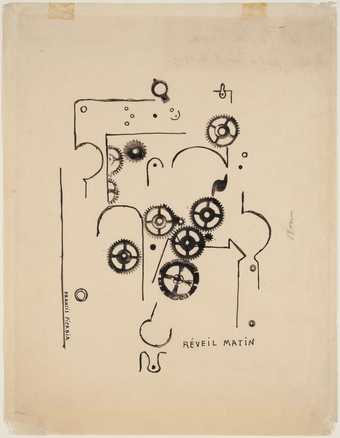

Francis Picabia Alarm Clock

1919