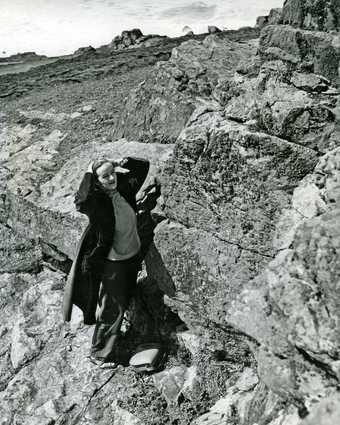

Barbara Hepworth walking on the cliffs near St Ives, Cornwall, 1950

Pictorial Press Ltd / Alamy Stock Photo

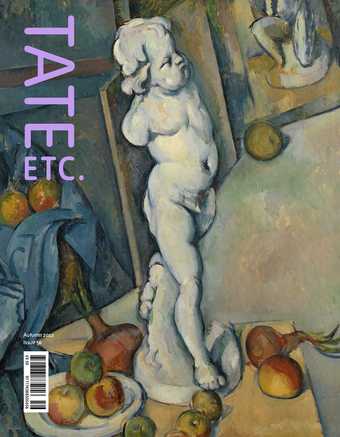

Listen to this article

I have been thinking about Barbara Hepworth (1903–1975) lately, and her connection to the land. For those familiar with Hepworth, this is perhaps the first thing that comes to mind; she famously stated that all her early memories were ‘of forms and shapes and textures. Moving through and over the West Riding landscape with my father in his car, the hills were sculptures; the roads defined the form.’

From the 1950s onwards, she sometimes titled her sculptures after specific places, often located near St Ives where she had moved in 1939, and she attributed her use of string in sculpture to the experience of the Cornish landscape, writing: ‘The strings were the tension I felt between myself and the sea, the wind or the hills.’ Yet, beyond the visual similarities between the forms of landscape and Hepworth’s sculptures, this connection offers a view into her deeper philosophy, her engagement with politics and society, and – perhaps contradictory to the bucolic pastoral scenes they can evoke – her interest in man-made technological advances.

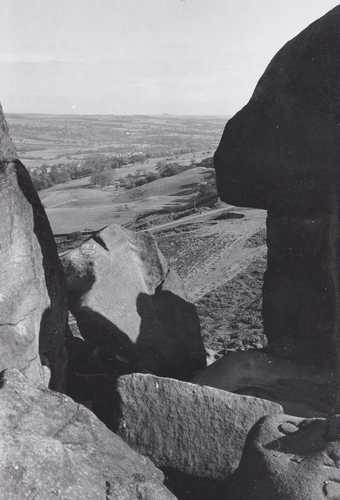

Cow and Calf rocks above Ilkley, West Yorkshire, photograph commissioned by Barbara Hepworth, 1964

The Hepworth Photograph Collection. Photo: Lee Sheldrake/Penwith Photo Press

Barbara Hepworth was born in Wakefield in 1903 and grew up surrounded by the dramatic landscapes of Yorkshire. These forms would become enduring inspirations. As she entered the last decade of her life in 1965, she commissioned photographs for a book, Drawings from a Sculptor’s Landscape, of the Cow and Calf in Ilkley, rock formations that, according to local legend, were created by the giant Rombald splitting the great rock in two while running away from his angry wife. After moving to St Ives, Hepworth wrote lyrically of the impression Cornwall made on her in her 1952 monograph Barbara Hepworth: Sculptures and Drawings, highlighting our bodily relationship to landscape but also the histories one can read within this material world, and the connection between the surface and the core of the earth:

The sea, a flat diminishing plane, held within itself the capacity to radiate an infinitude of blues, greys, greens, and even pinks of strange hues: the lighthouse and its strange rocky island was an eye; the Island of St Ives an arm, a hand, a face ... The incoming and receding tides made strange and wonderful calligraphy on the pale granite sand which sparkled with feldspar and mica. The rich mineral deposits of Cornwall were apparent on the very surface of things; quartz, amethyst, and topaz; tin and copper below in the old mine shafts, and geology and pre-history – a thousand facts induced a thou- sand fantasies of form and purpose, structure and life which had gone into the making of what I saw and what I was.

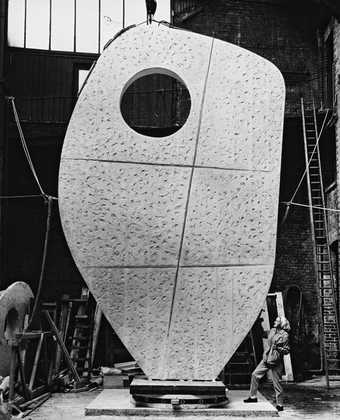

Barbara Hepworth’s bronze Single Form (Chûn Quoit) 1961 photographed overlooking St Ives Bay, June 1963

© Bowness. The Hepworth Photograph Collection. Photo: Studio St Ives

A thousand facts induced a thousand fantasies – Hepworth could be speaking of the legends spawned by Yorkshire’s extraordinary rock formations, and she found Cornwall equally steeped in myths and legends relating to the land. In 1937, the scientist J.D. Bernal, a friend of Hepworth, wrote an essay on her work in which he aligned her abstract sculptures with the menhirs of Cornwall, the latter described in spiritual terms as ‘central shrines’, or ‘a means of egress for the soul’. Hepworth embraced the ancient histories of Cornwall and their spiritual significance, describing the landscape near Zennor as ‘a place to visit where we can feel at one with God and the universe’, while noting in 1972, ‘I’m very aware of Ancient Britons, just as I am aware of my great-great- grandmother.’ In refining her sculptural forms to geometric shapes, she aimed to create a universal and timeless language, one which, like neolithic monuments, also spoke to contemporary society.

A Cornish neolithic chamber tomb, Chûn Quoit, believed to have been built around 2400 BC, provided inspiration for Single Form (Chûn Quoit) 1961. This shield-like form was created during the development of the monumental Single Form 1961–4 for the United Nations Headquarters in New York. At the unveiling of the sculpture, Hepworth said that she hoped it would ‘give us a motive and symbol of both continuity and solidarity for the future’, something that was perhaps equally applicable to the ancient societies who created Chûn Quoit.

Barbara Hepworth

Sculpture with Colour (Deep Blue and Red) 1940

Painted plaster and string

11.5 × 15.2 × 10.7 cm

© Bowness. Photo © Tate

It was not only the historic landmarks of Cornwall that inspired Hepworth. In 1962, the telecommunications satellite Telstar was launched into space, and the Goonhilly Satellite Earth Station was established in Cornwall to communicate with it. Hepworth was invited to visit the site in 1963 and recalled: ‘I was invited on board the first one [dish] when it began to go round, and it was so magical and so strange. I find such forms of our technology very exciting and inspiring.’ She made sculptures of scooped semi-circles, including the interactive Four Hemispheres, cast in lead crystal, which invited the viewer to swivel the dish-like forms, to face one other – or out into space. In 1970, she wrote: ‘I think we’ve all assimilated a great deal of scientific discovery – the sensation of space, as well as a new conception of the universe.’

Barbara Hepworth

Curved Stone with Yellow 1946

Painted stone

14 × 26 × 25 cm

© Bowness. Private collection, courtesy of David Wade Fine Art Ltd. Photo courtesy of Hazlitt Holland-Hibbert

The space race throughout the 1960s captivated Hepworth’s imagination, and her experience of celestial bodies from the ground was heightened by her situation in St Ives, where the sun, moon and sky are insistent presences. As she often stated, the climate there allowed her to carve outside all year round, and at Trewyn Studio, where she had moved in 1949, her external carving courtyard was accompanied by beautiful gardens in which to situate her larger works. She wrote to Ben Nicholson, her former partner and fellow artist, in 1966: ‘It is midnight 4th May & full moon! I have just been in the garden & in this light everything is strange & new. The flowering cherries & bushes are like stars. The sculptures strangely huge & ethereal. The moon is at right angles to my new “thinking room” (no stone dust allowed!) & the fierce and gorgeous moonlight gives a new dimension to all things.’

The feeling of connectivity to the landscape was no doubt heightened by living in a small town, where much of the industry was bound to the land, or sea. In August 1946, recovering from a bout of bronchitis while working frantically on new work for her first solo show since the war, she wrote to her friend, the political activist and writer Margaret Gardiner: ‘the weather is unendurable – rain all the time – culminating in a storm last night of such ferocity that we lost a large section of our roofing ... far worse a Breton crabber was hurled up on the rocks & all hands drowned.’

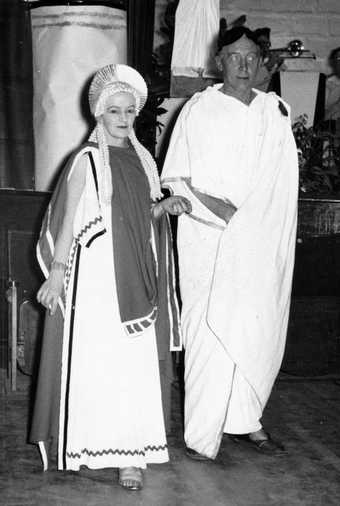

Barbara Hepworth at Goonhilly Satellite Earth Station, near Helston, Cornwall, c.1966, photographed by Ander Gunn

Photo © Ander Gunn

Hepworth became involved in local politics, particularly as they related to conservation of the land. In 1963, she wrote in protest of the proposal to reopen a tin mine near St Ives, stating it would be ‘a crime, on our part, if we do not preserve for our children what we ourselves have been bequeathed’. In an interview published in 1970 she described the ‘menace of pollution’ as a ‘threat to life’, akin to the atom bomb that had been dropped on Hiroshima. This parallel, no doubt considered at the time as hopelessly alarmist, is now echoed in the urgent concerns of contemporary environmentalists, and Porthmeor Beach, overlooked by the studio Hepworth painted in from the 1960s, has become a regular site of Extinction Rebellion protests.

Following the war, the ability to experience the landscape anew became a symbol of freedom regained and life emerging from the spectre of death. Hepworth wrote to critic E.H. Ramsden around the end of the war: ‘I feel refreshed today, because I went with the children to a horse & cattle show – set in a vast field surrounded by sea, Trencrom & all the lovely landscape. It was sheer joy to see the movement & form of exquisite hunters, trotting horses, cart horses, bulls & human beings in the brief sunlight ... I think I’m slightly intoxicated these days by the beauty round us here in living things. Too great a contrast to “all the rest” but thank God for it.’

In October 1945, some five months after VE day, she wrote to Nicholson of her delight in the newfound freedom to roam the land, its tremendous impact on her work and her delight in what she saw: ‘there must be magic in this country round here.’

Barbara Hepworth: Art & Life, Tate St Ives, 26 November 2022 – 1 May 2023. Curated by Eleanor Clayton, Senior Curator, The Hepworth Wakefield, Anne Barlow, Director, Tate St Ives and Giles Jackson, Assistant Curator, Tate St Ives. Supported by the Barbara Hepworth Exhibition Supporters Circle. Organised by The Hepworth Wakefield in collaboration with the National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh, and Tate St Ives.

Audio narration by Radhika Aggarwal.

Magic in this Country: Hepworth, Moore and the Land, curated by Eleanor Clayton, opens at The Hepworth Wakefield in January 2023.