Introduction

Within the context of the European research project PERICLES, eight people engaged in different aspects of digital preservation came together to conduct a series of conversations. The primary aim of these conversations was to explore the different ways in which the ‘Lives of digital things’ are thought about through different areas of digital preservation practice.

Represented within the group were those who work within the contexts of records management and archives, art conservation and research data, practitioners and academics. One of the distinctions which emerged early on in our discussions was the significance of whether digital preservation was being carried out during the ‘active life’ of the digital thing or in an ‘end of life’ scenario. We also questioned the binary nature of this distinction and were interested in engaging with the notion of continuum theory which has been developed within the records keeping community, particularly at Monash University in Australia1 . Traditionally an ‘end of life’ approach has been associated with custodial archives, where the challenge is to ensure the stability of an authentic object which can act as evidence. However in other contexts, such as the management of records, scientific research data and digital artworks, digital preservation may be carried out during the active life of the digital objects. Active life preservation makes change a key issue, not simply in the sense of preventing change but in terms of managing change as part of the digital object’s active life.

The digital is disrupting the records and archives world. Custodial archives are not well equipped to consider the digital workplace. According to the traditional life-cycle model when the records are quite old and ready for transfer into the archive, that is the point at which traditionally the archive would engage in their preservation. Within a digital environment the time-scale of twenty or thirty years may be too long for effective preservation and access of those records. Many workplaces are also not able to effectively manage their digital records and there is a strong suggestion that paper based practices do not translate in a straightforward way into the digital.

The themes discussed during our meetings included the suitability of the concepts of ‘a life’ and ‘a thing’ in relation to digital objects, conceptual frameworks and models for digital preservation, synergies between the different approaches and finally points of transition and points of tension.

Terms

During the course of the Pericles project it became clear that there was a need to articulate underlying assumptions regarding the culture in which preservation was enacted. Here, I am using the term ‘culture’ in the way defined by the sociologist Karin Knorr Cetina, where culture ‘refers to the aggregate patterns and dynamics that are on display in expert practice and that vary in different settings of expertise’ (Knorr Cetina 1999, p. 8). Within the Pericles project, domain context was understood as ‘the necessary background information to use or understand a digital object’ (see glossary, http://pericles-project.eu/page/glossary). Context of use is also addressed and is understood as relating to information external to the digital object that is relevant to its use. The domain context is closely linked to culture and determines the types of questions that frame expert preservation practice. In the field of digital preservation there is more attention given to how to preserve digital things in a practical and sustainable way than there is to how success is characterised within different preservation cultures.

Within the world of digital preservation there is an important distinction between bit preservation and digital preservation. Bit preservation is concerned solely with the stability of the digital bits that make up a digital object. Digital preservation speaks to a more holistic and culturally specific approach where success might be judged not simply by the stability of the digital object and our ability to understand it but also through an understanding of the value and use of that digital object. It is the cultural context of digital preservation that determines what is important to preserve about that digital object, for example whether the object needs to act as evidence, or remain identifiable as authored by a particular artist, or enable a scientific experiment to be repeated.

Within the field of digital preservation, there are those who argue that as it is all data, the context or culture in which the digital object resides does not significantly matter in its preservation. However, a focus on the social fields of preservation and preservation practices challenges this view. In the development of systems, we increasingly see attempts to model and automate processes and decisions which reflect domain specific professional expert practice. There are important drivers associated with sustainability which are behind these developments, however there is a risk that those elements of practice which are only to be understood by reference to specific cultures fail to be fully considered in the development of such models and systems. In the spirit of reflective practice, this group therefore convened in order to examine our different cultural perspectives, with particular reference to the provocation encapsulated in the title ‘The lives of digital things’.

There is currently little awareness of the different cultures and practices within digital preservation. Within the contemporary art museum we have been engaged over a number of years in articulating how we might act as responsible custodians to collections, whilst also allowing for change as the artwork unfolds. Increasingly our work in the conservation of digital artworks has crossed over with other areas of digital preservation and here we found it important to explain how our work on the conservation of digital artworks is different in approach to other practices such as archival practice. In the Netherlands a project called New Strategies in the Conservation of Contemporary Art, led by Professor Renee Van de Vall, focussed on the idea of a biographical approach to understanding the life of artworks. This approach has been highly influential for the art conservation community (for more information see Appendix Two). The contemporary art conservation community also needs to articulate an account of the artwork as a continuum before and after it entered the museum, hence continuum theory from records management also has clear resonance.

During our discussions, Anna Henry noted that in the UK, records managers and archivists are seen as different professions, while in Australia a continuum approach is adopted, removing the rigid custodial lines between records managers and archivists. The centre for continuum theory in records management is currently at Monash University, in Australia. Anna Henry observed that in the UK and elsewhere ‘archivists are often hesitant to “interfere” in the life of an active record’. Digital preservation standards seem to follow the life-cycle driven approach and assume that there will be a point in time when an active object is handed over to another institution who are then responsible for its preservation. Many of the models which underpin systems development, such as OAIS, have been associated with a life-cycle driven approach to digital preservation practice. This may work well in repository environments where the primary goal is stability and access but this causes difficulties in contexts where practitioners are responsible for the preservation of artworks that are still undergoing active change.

The conversations which were held within this Community of Practice group considered synergies and things which we could learn from different disciplines, as well as points of divergence.

Main themes discussed

The ‘life’ and the ‘thing’: The Thing

We began by discussing the phrase ‘The lives of digital things’. Many participants had difficulties with this phrase; objections to the notion of a ‘thing’ included Kevin Ashley’s concern that the term ‘thing’ implied a discrete object, whereas he does not see ‘everything [that is] digital… as being a set of isolated objects but rather a complex set of interconnected material’. Barbara Reed made the point that records are a manifestation of content. A good record is accompanied by waves of context and connections. A record is never a single object; it is always an object with connections. A record cannot be separated from the events that precipitated it nor the person who created it or was involved in it. Within Record Keeping practice, Barbara Reed noted, in order to make the meaning of records understandable over time, further context is added to enable others from further away (space/time) to understand the record. This is the purpose of archival documentation systems, an extension of records systems, which continually add to the context/meta-data about the record for as long as it is feasible/desirable to do so.

The ‘life’ and the ‘thing’: The Life

The metaphor of the ‘life-cycle’ is something which has been much discussed within the field of digital preservation. Luciana Duranti provided the group with an historical perspective and remains a strong advocate of the metaphor of a life-cycle, which she points out is derived from the notion of the life-cycle in nature, for example the carbon cycle, and not human life2 It is therefore circular and not linear. Within the group, we also heard advocates of continuum theory, and also a cultural biography model derived from ethnography which has been explored in relation to artworks.

Barbara Reed pointed out that often the assumption behind the use of the metaphor ‘life-cycle’ is linked to a linear cycle, and traditionally in records the transition is from life, to death and perhaps to life after death. However it is not really a ‘cycle’ that is being referred to here, rather a lifespan; ‘…for records ….. the reverberations of actions documented in records, can and do invalidate simplistic life-cycle metaphors quite quickly’.

Luciana Duranti argued that the life-cycle of a record involves ‘a progression, a sequence, and either an end or a transformation based on use, reuse, remix, flow into derivative works etc.’ Luciana Duranti also pointed to the history of the use of the term ‘life-cycle’, noting that in the 1940s Philip Brooks advocated for co-operation with the creator and the selection for preservation to be early in the life of the record. She believes that it was only later in the 1960s that a dichotomy arose between the archive and the records manager, when in the United States the sequence of activities involved in the life of a record were carried out by different actors, namely the records manager and the archivist. Duranti points to theories within France and the UK which continue to advocate against a dichotomy between the role of the archivist and the records manager. In the theory of the three ages of records (Duchein, 1970s), each age is directly connected to the value of a record conceived of in terms of usefulness. This is summarised by Duranti as the Administrative age (useful to the creator), Intermediate age (decreasing usefulness to the creator, increasing usefulness to others), Historical age (general usefulness). Duranti refers to the articulation of the life-cyle by the United Nations ACCIS Report of 1990 which described the functional requirements of an information system: records creation, appraisal, control and use, disposition. This was later simplified in 1997 by the International Council of Archives Committee on Electronic Records: conception of records, creation of records and maintenance of records (including preservation and use). This is helpful in distinguishing records, which may essentially be valued for their usefulness, but it raises questions regarding other types of digital objects, such as digital artworks, which have a range of different values associated with them.

This led to a discussion as to whether the metaphor of the ‘life-cycle’ is useful for thinking about the management and preservation of records. To preserve a record is to preserve evidence of facts that are outside the record. The metaphor of a ‘life-cycle’ for Duranti points to the dependency on the environment in which a record occurs – a documentary context, a legal context, an historical context, a technological context, a procedural context etc. Imagine, for example, an aggregate of records that have been produced as operational records for a business, which are later used for a legal case. These are the same records but they have been used for a different purpose and become the records of the court, and are therefore reborn as different records in different contexts. The important point is that the records maintain their identity while conveying different meanings and different actions. The aim is to preserve intact what the object was meant to reveal, or inadvertently reveals.

Related to the discussion about whether we are preserving an object or not, Barbara Read argued that for her records are always socially situated and identifying them as such helps to bring to the fore the social conditions of creation and the environment of action, including relationships, people, environments, social systems, mandates and what impacts action. A record comes more as a flow than as a thing. For Reed the notion of a single object is incorporated into the notion of the life-cycle whereas within continuum theory records are not treated as an end product but as processes.

Questions were also raised about what happens at the end of the life-cycle? How do you go from ‘dispose’ to ‘create’? In this regard the analogy to the carbon cycle does not entirely hold. There was disagreement about what the life-cycle model and the continuum model represent – one view of the lifecycle model was that it represents a continuous chain of custody marked by activities, another that it represents actions of which a record is the outcome. One view of the continuum model was that it is a static model which represents a static multi-view of the entity or record.

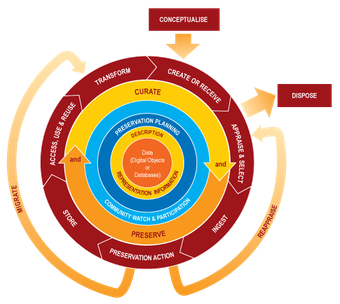

Fig.1

Key elements of the DCC Curation Life-Cycle Model, Sarah Higgins (2009)

See Sarah Higgins, The DCC Curation Lifecycle Model in Bulletin of IEEE Technical Committee on Digital Libraries, vol.5, no.1, Spring 2009, ISSN 1937-7266.

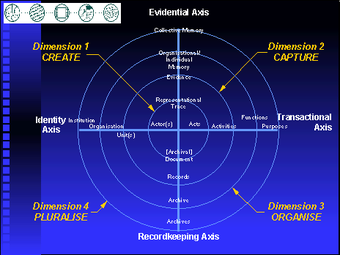

Fig.2

The Records Continuum Model, Monash University 1998

Reproduced in Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:The_Records_Continuum_Model.gif, Accessed 10 October 2017

The discussion moved on to thinking about the different senses in which artworks are objects. One aspect that came to the fore was the notion of intention embedded in our conception of the role of the artist. Artworks can also be interpreted as records of artistic practice; with the manifestations of an artwork changing over time. Increasingly artworks are considered to have a living archive of information running alongside them. In some obvious ways the language of the life-cycle model does not fit with artworks, as for example within the contemporary art museum artworks are not the types of object which can be assessed according to their usefulness to the creator or others in any straightforward way. Museums rarely de-accession and artworks seldom become the raw material for other artworks, unless this is a specific part of the artist’s practice.

As mentioned in the introduction, the research group in the Netherlands New Strategies in the Conservation of Contemporary Art, introduced the notion of ‘cultural biography’ as a way of thinking about contemporary artworks. This concept derives from cultural anthropology3 and was explored as a means of incorporating changeability into conservation theory. The research identified and considered the watershed events were in the life of contemporary artworks and found them to be different from those of traditional objects. For example, exhibition or display is often key within the lives of digital artworks and has far greater impact on the biography of a work than found in the lives of traditional artworks. It is also the case that a work’s biography was found to be complex, allowing for different time-lines and different dynamics. Also incorporated into the notion of a biography is the study of the practices in which these biographies are being constituted. Here the practices connect the objects, the things that people do with them, the places and locations of activity on a day-to-day basis.

Preservation Environment

One of the central differences of opinion within the group concerned the question of whether preservation could only take place in a ‘preservation environment’? Currently our systems for bit preservation require stasis in order for current methods of fixity to detect undesirable change, however this need for fixity is at odds with practices of preservation which want to allow for future iterations of artworks and the active accumulation of the record. Luciana Duranti argues for the need for there to be a transition point to a preservation environment and she is currently working with cloud providers to look at how this might be created using a firewall in the cloud. In the digital environment it is important to preserve all the key properties and relevant context so that the digital record or archive can remain and serve as evidence. The concern is that digital material is so easy to tamper with, change, or corrupt that unless it moves into the hands of a neutral third party and out of the influence of others, it can no longer claim to be evidence, nor authentic.

Transition points

Four types of transition points were discussed. Firstly, in the transition from active life of a record to a preservation environment.

Secondly, a transition point was identified within records management when there is a change of formats. When formats cease to be viable this creates a transition point or appraisal point where questions arise regarding migration or emulation.

Thirdly, from the active life of an artwork to an artwork being seen as heritage. With the Dutch research project New Strategies in the Conservation of Contemporary Art and through the work of Vivian van Saaze and Renee van de Vall, ethnographic methodologies have been used to study artworks within a museum in order to explore the validity of the sharp division that is perceived to exist between the stage in which a creator is involved with the artwork and the stage in which it is being preserved, perhaps when it becomes heritage. This was described by Renee van de Vall as a ‘seizure between these two stages’. Research showed that in fact these two stages were not so clearly defined.

Fourthly, within contemporary conservation practice there is a transition point between conservation practice during the life of the artist and how that practice might be affected on the death of the artist.

Value

The focus within records management is on use value, often linked to notions of evidence. In contrast the value most prominent within fine art is display. Conservation is also governed by a set of values and responsibilities to the creator that are distinct from those within a records management environment. The ethical responsibilities of a records keeper are largely focussed on providing an authentic record in order to provide evidence and enable accountability. The ethical responsibilities of a contemporary art conservator are largely focussed on ensuring that the work can continue to be displayed in a way that maintains the identity of the artwork, an identity which is often primarily determined by the author of the work, namely, the artist. Unpicking what it means to continue to enable a work to be displayable, understanding how an individual work might unfold during its life, as well as acting as a broker between different stakeholders are key elements of contemporary art conservation practice. These capabilities sit alongside a practical understanding of the material or technical nature of the work.

Life-cycle as it is defined within records management is therefore not appropriate to artworks because the transitional moments are not mappable. As Renee van de Vall underlined, the key moments in the life of an artwork would traditionally be: conception or making, execution, leaving the studio, circulation in the art world, acquisition into a collection, exhibition and display. The life on an artwork within the collection is still considered ‘active life preservation’, both during the life of the artist, who may re-engage with the work at different points, but also beyond the life of the artist, as the work continues to be exhibited and displayed.

Scale

One of the distinctions between the different practices of record keeping, archival practice and conservation practice relates to the question of scale. Archivists and records managers tend to operate on a large scale, thinking in terms of aggregates of material, whereas it is one of the defining features of contemporary art conservation that it is focussed on the individual artwork: the idea of the specificity of the individual work of art is fundamental to the practice. When attention is paid at the object level within archival practice it is usually linked to digital preservation and the focus is usually on formats, rendering and migration. When thinking about the impact of scale, for example, being responsible for 250 objects which have all been identified as being very important, rather than 250,000 objects – an analogy was drawn with the differences between working on a national or international scale on public health issues, and working on the individual scale as a doctor. These are very different practices and have different areas of focus. Some things warrant individual attention and other things are best addressed by general measures and policies.

Standards, Models and Change

Standards and models such as OAIS are felt to play down the ongoing events that occur on the objects both within and also outside the repository space. From a record keeping perspective these events are more than simply ‘administrative’ but rather form part of the trail of evidence of actions which allow assertions to be made about the authenticity of the object over time.

Models

It was noted that models such as OAIS were designed for the paper world, but within digital spaces different ways of managing material are emerging

Models do have an impact on how systems are built and therefore on how digital material is managed. Within the discussion of OAIS, the distinction between an object – albeit with different levels of aggregation – and a record, becomes significant, because the language of the preservation of digital objects tends to suggest a custodial environment, whereas it might be possible to manage material outside a custodial environment.

Within the museum, there was a desire for a model that mirrored the rhythms of the museum and the contemporary artworks within the museum. The lack of an appropriate model had led to a lack of systems that reflect those rhythms of display, conservation and maintenance, including moments when a number of different interested parties, including conservators, artists and curators, re-engage with the work.

Context

The discussion regarding the term ‘context’ revealed a good deal about the different practices of digital preservation.

The context in which we work

Across the practices of record keeping, archiving, and conservation some processes are shared, particularly those associated with bit preservation rather than digital preservation. There are also some similar needs in terms of infrastructure and tools. However, what we consider important to preserve will be determined by the values and drivers underpinning the different domains of application. For example, for someone working in the context of maintaining legal records or evidence, this context will determine what needs to be preserved in order to maintain the authenticity and integrity of the record. Within the context of contemporary art, authenticity is also an important concept but what might be needed in order to maintain the authenticity of an artwork may be quite different. For example, it may relate to maintaining the original concept of the work.

During our conversations one of the questions raised was ‘Can anything be a record?’. It was noted that at a certain level of abstraction it does seem that practices that have developed within a particular context can be usefully applied to other contexts and sometimes this helps to highlight what is foregrounded within a particular practice and perhaps neglected within another practice. For example, at a certain level of abstraction, concepts in the world of record keeping may work very well in the world of research data. However, there comes a point when the differences in emphasis become significant. For example, the importance of concepts such as evidence and authenticity assume a greater significance in the life of records than perhaps for other types of digital content. There are also other areas where functions only have relevance within a particular digital domain and it is at this level of detail that the ability to take concepts from one domain and apply them to another, break down. For example, in the case of digital artworks, many works involve the user, the viewer, the spectator and the player. There may be different levels of interaction, from experience to action. They may resemble games; the game will stay the same as long as the rules remain, but the interaction will always be a little bit different. The term ‘record’ does not capture this. However there may be value in thinking about managing aspects of an artwork as a ‘record’, as a useful disciplinary lens through which to manage the artwork, for example when thinking about ensuring that the record that runs alongside the life of the artwork is captured.

The description of context in archival descriptions

‘Context’, in archival descriptive practice, has traditionally focussed on documenting the circumstances of the creation of the object and to a limited degree the environment in which it was created. This may include the social context which might be gathered in order to aid the understanding of the object. Fundamental to archival practice is the notion of neutrality.

Contextual dependency

The group identified the notion of contextual dependency which represents a dependency that a digital object may have on material supplied from its context, perhaps a networked dependency or a social dependency. This is a dependency that will affect its ability to continue to be displayed correctly in the future and therefore presents a preservation challenge within an active life preservation environment such as the contemporary art museum.

Record keeping for a record?

Context was distinguished from record keeping related to a particular record. This was identified as essentially the transactions that take place on an object; the ‘who did what when’. Within record keeping practice, the environment that the creator was working in is described, as is the ongoing chain of custody or chain of provenance of the record; much of this activity is record keeping about the record. This practice is essential in allowing us to make assertions about the reliability of an object, whatever its different context.

Participatory record keeping and the proliferation of interpretations

Within the archive community the documentation of social context is largely left to the users to document. There have in recent years been many projects, such as that held at the UK’s National Archives4 , among many others, which have invited volunteers to supplement archival description by adding information that they may have through their specialist knowledge and use of the material. This is valuable, but is not seen as one of the core roles of the archivist. This increased creation of data and information by users, as part of a greater participatory culture, is becoming part of institutional archiving and one of the consequences of this is a proliferation of interpretations.

Within an art context Renee van de Vall identified a ‘participatory force’ in many contemporary artworks, meaning that users do not only interpret a work but also add to it. These spin-offs or ‘Nachwuchs’ (offspring) blur the boundaries between what one might consider the object and what might be the environment or context.

This discussion is also very present within the context of recent museum practice related to the collecting of live performance-based artworks. For example, in the context of a research network meeting for ‘Collecting the Performative’ at the Van Abbemuseum, the work Read the Masks. Tradition is not Given (2008) by Petra Bauer and Annette Krauss was considered. During the discussion it was decided that the responses from the public to this work should become part of the artwork. Previously these comments had not been collected from the general audience but at the meeting this view shifted, demonstrating that the boundaries of this work weren’t fixed and could change. This illustrated the point that overtime the status of this type of contextual material can shift within all of our disciplines.

Barbara Reed also brought up the example of current moves by some communities, such as the survivors of child sexual abuse, to have control over their own records. The current situation denies a sense of agency by these communities over their records; the rules about access and control over records are written for the institutions, rather than for individuals, begging the question of whether the subject of the record have some agency over it?

There is also another model emerging where there may be a neutral third party that holds records, such as medical records, and both the medical establishment and the patient have equal agency and rights with regard to those records. Here we are seeing a potential shift in power emerging in terms of who can control the record. In the area of health care it may be that someone might decide that the podiatrist should not have access to the records of the psychiatrist regarding a particular patient, however currently the technology of electronic health records does not allow for such nuanced management or participation by the patient.

Control

Within archival, record keeping and conservation practice it is the responsibility of the practitioner to ensure that the record, object or artwork is preserved and accessible and also that records are kept that relate to changes that may occur. Decisions are made and risks are assessed in accordance with professional practice. Within the archive this is translated into a responsibility to offer up an object that is pristine and un-tampered with, which can then be interpreted by scholars. Within the fine art community this sense of being able to hand to future generations works of art creates a point of tension because of the unfolding nature of many forms of contemporary artwork. Through working closely with the artist over many years views about the work may evolve over time, and may involve how the work is accessed and encountered by the public, the form of the work, and ultimately what is important to preserve about the work.

Appraisal

We discussed the professional domain of appraisal which belongs to both practices of record keeping and archival practice. Barbara Reed described this as ‘working out what to document and how long to keep it for’. Within traditional archival and records keeping practice the focus of appraisal is on the moment when a decision is made to transfer material to the archive. In records continuum terms, it is an ongoing continuous and repeated process.

Within digital archives the decisions about whether material is to be migrated is also referred to as appraisal.

The term ‘appraisal’ is not used within conservation practice and does not fit well into this context. This is partly because within the fine art museum, once it has been agreed that legal title for a particular artwork will pass to the museum, and it is extremely rare that a museum will de-accession a work. Although some processes may superficially look similar, for example consideration of an artwork’s importance and relationship to the collection, once examined at a granular level the differences of the art context and the archival or recording keeping context make the adoption of the term unhelpful. Decisions may be made regarding what is privileged at any particular moment, and that might be considered a form of appraisal, as might risk assessments regarding the vulnerabilities of a particular work. While reflecting some similarities, the concept of ‘appraisal’ does not easily map the practices within contemporary art conservation. This might in part be to do with the fact that the fine art museum is working on the object level regarding its art collections. Not only are artworks themselves not de-accessioned but highly detailed information about them is also largely desired rather than discarded.

The Art Object

One of the distinctions between an art object and a record is in the notion of intentionality. We do not in the museum talk about unintended artworks, whereas within the record keeping environment there are unintentional records and records that are almost ancillary.

The contemporary art conservation community has adopted, rather liberally, the notion of significant properties, however one interesting recent development that was noted in the Media in Transition conference5 was the move away from the idea of a fixed set of properties, to the idea that in different moments in the life of an artwork certain properties might come to the fore while others recede. Traces may remain of properties that may have been more prominent in a previous moment in the life of the artwork. Renee van de Vall presented an example of an artwork by Joost Conijn. This work is a wooden car that drives on wood as fuel, which forms part of a large series of connections. Much of its meaning relates to the journey the artist made and the resulting video. The car is similar to a prop linked to the event of the travel. The physical components are important elements, for example the fact that it is made from wood and it smells a certain way. Conservation decisions will probably mean that certain elements may change, for example the engine and the oil may be removed, so decisions will be made about what must stay the same and what must change. However it seems that the physical components of the record are more important in the artwork than in the archive.

Conclusions

‘The constant is change’ Kevin Ashley

These conversations covered many topics which were relevant to the EU digital preservation project Pericles and helped us to consider the implications of embracing active life preservation both inside and outside institutional settings. By examining different practices we were able to gain a greater understanding of the impact of context on digital preservation. There was also surprising resonance felt in the consideration of emerging questions surrounding the ownership of the record, which pointed to an important area of development in all our practices.

We would like to thank all of those who participated in these conversations for their generosity of thought and the quality of their thinking, which indeed proved to be fruitful and enjoyable in equal measure.

Appendix One: ‘Life-cycle’ by Luciana Duranti

The idea that records have a life is linked to the quality of naturalness that archival authors have traditionally associated with the concept of archives, and the metaphor refers to nature lifecycle (e.g. carbon cycle, water cycle), rather than to human life, as many think, which means that the records life-cycle is circular, not linear.

This idea recurs in the international literature of records management and archival science since the 1940s, especially in the UK, but was elaborated in the United States. The phases or stages of records life have since varied from country to country and through time, as have the criteria determining which they are, but everywhere the concept of records life cycle involves a progression, a sequence, and either an end or a transformation based on use, reuse, remix, flow into derivative works, etc..

In 1940, American author Philip Brooks argued that “the several steps in the life history of a given body of documents” involve creation, filing, appraisal, and either destruction or permanent preservation for a variety of uses; that “the earlier in the life history of the documents the selection process begins, the better for all concerned. And the earlier in that life history that co-operation between the agency of origin and the agency can be established, the easier will be the work of all” (Brooks, 1940, pp.223-226). Thus, the records life moves from the responsibility of the “office manager” to that of the archivist in a seamless way through the exercise of the appraisal function, and later evolves and changes as a result of research use.

However, in the 60s, the growing dichotomy between records management and archival management in the United States reduced the meaning of the expression “records life-cycle” to a mere sequence of activities carried out by separate actors (i.e. the records manager or the archivist). It is to this dichotomy that Canadian archivist Jay Atherton objected when he proposed that such expression be substituted by a “records management-archives continuum” in four phases, where the guiding criterion for distinguishing the phases is service, as follows (Atherton, 1985-86, p.51):

Ensure the creation of the right records, containing the right information in the right format

Organize the records and analyze them to facilitate availability

Make the records available promptly to those who have a right and a requirement to see them

Systematically dispose of records that are no longer required

Protect and preserve the information for as long as it may be needed

Jay Atherton’s continuum is very similar to Philip Brooks’ records life history in that it envisions an ongoing collaboration between the creator and the designated preserver since the creation of the records, and presents a sequence of integrated activities that begins at creation and ends at preservation, after which time use will determine how the life of the record will progress, if at all.

Interpretations of the records life-cycle concept

In the past half century, North America has settled on the concept of the records life cycle as articulated in the 1950s and 1960s while in practice moving towards the Atherton’s concept of continuum, primarily because of the need to acquire control of “machine readable”, “electronic” and today “digital” records of enduring value as soon as possible after creation and, possibly, even before then, by designing reliable recordkeeping systems. During the same time span, several initiatives have re-examined the life cycle concept giving it different spins, albeit often maintaining its name.

France, in the 1960s, developed the theory of the records three ages (Duchein, 1970), based on to whom the records are useful, as follows:

- Administrative age: usefulness to the creator

- Intermediate age: decreasing usefulness to the creator, increasing usefulness to others

- Historical age: general usefulness

A decade later, most continental Europe moved towards the idea of structuring the records life cycle on the basis of the records location, de facto supporting the North American dichotomy between the management of the records for the purposes of the creator, and the management of the records selected for permanent preservation for general purposes, as follows:

- Records in the creating office

- Records in the central registry (creator)

- Records in the intermediate archives/records center (preserver)

- Records in the historical archives

Great Britain, with the Grigg report issued in 1954, established the principle of collaboration between the record manager and the archivist since the beginning of the lifecycle, especially in relation to appraisal. Discussing the British situation, in 1980, Felix Hull developed the theory of “movable responsibility”, according to which record manager and archivist work together throughout the life cycle but the responsibility of the former gradually diminishes as the responsibility of the latter grows. Indeed, this approach is very similar to Atherton’s continuum, and it is fully implemented for public records.

In the 1990s, the issues presented by records created in electronic systems began to dominate the discourse related to the records life-cycle. Instead of renouncing the concept though, it was preferred to change its meaning and to design its stages so that it would serve the identified need. Thus, the United Nations ACCIS Report of 1990, although still naming the newly conceived process as a records life-cycle, described the functional requirements of an information system in relation to the following idea of the life-cycle.

Records creation and identification

- Appraisal

- Control and use

- Disposition

A few years later, in 1997, the International Council on Archives (ICA) Committee on Electronic Records decided to rewrite in its guidelines for the management of electronic records the stages of the records life-cycle using as criterion “the archival function.” Accordingly, the stages were reduced to three:

- Conception of Records (including the design of the records creating and keeping system)

- Creation of Records

- Maintenance of Records (including Preservation and Use)

If one considers carefully the UN and the ICA models, one realises that, regardless of their name, they are not a reworking of the life-cycle model, but are two different expressions of the Australian records continuum model. In fact, differently from those models, the concept of records life-cycle involves a shifting of responsibility for the records from the creator to the preserver—no matter how seamless, and regardless of ongoing collaboration—and is based on the use and location of the records, on the purpose of the activities carried out on the records, and on the person responsible for those activities, the creator or the preserver. Does this mean that the concept of life-cycle had by this time fulfilled its function and finished its usefulness? Perhaps not.

Clearly, by the late 1990s, the focus of the concept was firmly established on electronic records. Simultaneously to the ICA, the UBC/DOD Project (1994-1997) developed its own version of a life-cycle for electronic records that was later embedded in the DOD Standard 5015.2 (1998). The criterion determining the stages of the life-cycle was the reliability and authenticity of the record system (Duranti, Eastwood, MacNeil, 2002):

- Creation in office space (before transmission): Make, send, and set aside

- Record-keeping in a central space (after transmission): Receive from outside and from inside the organization, and set aside

- Classification and scheduling

- Maintenance activities of all kinds and use

- Disposition

- Record-preservation in a central preservation space: Preservation activities of all kinds

- Dissemination activities of all kinds

While in this model the shifting of responsibility from the creator to the preserver is blurred by the fact that the electronic system is regarded as one entity with separate spaces and separate access privileges to such spaces, in the model developed a few years later by the first phase of the InterPARES project (www.interpares.org, 1999-2001), the division between the two stages of the life-cycle following under the responsibility of the creator and the preserver could not be sharper. The criterion on which the InterPARES concept of life-cycle is based is the status of transmission of the records. The model includes two stages, the first regarding the records of the creator, and the second regarding the authentic copies of the records of the creator.

It is generally accepted that it is not possible to preserve electronic records. It is only possible to preserve the ability to reproduce them. This is because, every time one retrieves a record, a copy of such record is generated. However, when copies are produced by the creator in the course of its activity, as soon as they participate in further activity and reference, they are again original records in the creator’s context. They behave and have to be treated as originals every time they are used and acted upon. This implies that any management activity carried out on those items is carried out on the creator’s records.

When the records of the creator are no longer needed for the ordinary course of activity and are passed on to the preserver, they cannot any longer be treated as originals because the creator has never used or acted upon the copies produced by the preserver for long term storage and preservation. These are authentic copies of the original records. If the records were to be reactivated for the use of the creator, then we would again have the records of the creator.

The implications of the different status of transmission of the records are key to the way they are managed. The creator can decide at any given time to give to its records the most useful, accessible, interoperable form, or the form that best serves its present and projected needs, and have as a result entities that we can call the records of the creator. In contrast, the preserver can only manage what it receives from the creator by making an authentic copy of it, and has no right to alter its documentary form, only its format.

Conclusion

The concept of records life-cycle has supported the management of records for several decades and its usefulness is not diminishing, especially at a time when records are increasingly created and maintained in online environments, and might have to be preserved in hybrid environments (i.e. in in-house as well as online records preservation systems). While, at the time the concept was developed, the shifting of responsibility from the creator to the designated preserver involved a flow of records from the physical custody of the creating office to that of a records center and later of an archive, in the future, this shifting of responsibility might involve simply the passage of the legal and intellectual control on records that continue to exist in the same online environment, being used, reused, adapted, and modified by different parties. In other words, it is very likely that the original life-cycle metaphor, which compared the life of records to that of natural entities, like water and carbon, will be for the first time truly applicable.

Bibliography

Advisory Committee for the Coordination of Information Systems (ACCIS), United Nations., Management of Electronic Records: Issues and Guidelines, United Nations, New York 1990.

J. Atherton, ‘From Life-cycle to Continuum: Some Thoughts on the Records Management—Archives Relationship’, Archivaria 21 (Winter 1985-86), pp.43-51.

P.C. Brooks, ‘The selection of records for preservation’, The American Archivist, III, 4 (October 1940), pp.221-234.

M. Duchein ‘Le pre-archivage: quelques clarification necessaires’, La Gazette des Archives 71, 4.e trimester, 1970, pp.225-236.

L. Duranti, T. Eastwood, and H. MacNeil, Preservation of the Integrity of Electronic Records, Kluwer Academic Publishers Group, Dordrecht 2002.

Great Britain. Parliament, Report of the Committee on Departmental Records, Cmnd. 9163, HMSO, London 1954 [Known as ‘The Grigg Report’].

F. Hull, ‘The Appraisal of Documents: Problems and Pitfalls’, Journal of the Society of Archivists, 6 (April 1980), pp.287-91.

International Council on Archives, Committee on Electronic Records, Guide for Managing Electronic Records From An Archival Perspective, International Council on Archives, Paris 1997.

International research on Permanent Authentic Records in Electronic Systems (InterPARES), http://www.interpares.org/, accessed on 1 February 2017.

T.R. Schellenberg, Modern Archives, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 1956.

Luciana Duranti – InterPARES Trust

Overview

My research aims to develop new knowledge on digital data/records/archives kept in the cloud and on methods for identifying and protecting the balance between trust and trustworthiness (reliability, accuracy, authenticity), privacy and access, secrecy and transparency, intellectual rights and the right to knowledge, and the right to memory and the right to oblivion in globally connected networks. It will propose law reform, and other infrastructural reform, model policies, procedures, and practices, and functional requirements for the systems in which internet providers store and manage digital material.

Research domains and cross-domains

The project is divided in five research domains and five research cross-domains. The research domains are: 1) Infrastructure: It considers issues concerning system architecture and related infrastructure as they affect materials held in online environments. Examples of areas to be investigated include: types of cloud and their reliability, types of contractual agreements and their negotiation, coverage, flexibility, costs, up front and hidden; 2) Security: It considers records issues relating to online data security, including: security methods, data breaches, cybercrime, risks associated with shared servers, information assurance, governance, audits and auditability, forensic readiness, risk assessment and backup; 3) Control: It addresses such issues as: authenticity, reliability, and accuracy of data, integrity metadata, chain of custody, retention and disposition, transfer and acquisition, intellectual control and access controls; 4) Access: It researches open access/open data, the right to know/duty to remember/right to be forgotten, privacy, accountability, and transparency; 5) Legal: It studies issues such as: the application of legal privilege (including extra-territoriality), legal hold, chain of evidence, authentication of evidence offered at trial, certification and soft laws.

The research cross-domains are: 1) Terminology: It is concerned with the ongoing production of a multilingual glossary, a multilingual dictionary with sources, ontologies as needed and essays explaining the use of terms and concepts within the project; 2) Resources: It is concerned with the ongoing production of annotated bibliographies, identifying relevant published articles, books, case law, policies, statutes, standards, blogs and similar grey literature; 3) Policy: It studies policy-related issues emerging from the five research domains and addresses record keeping issues associated with the development and implementation of policies having an impact on the management of records in an online environment; 4) Social issues: It analyses social change consequent to the use of the internet, including but not limited to use/misuse of social media of all types, trustworthiness of news, data leaks and their consequences, development issues (power balance in a global perspective), organisational culture issues, and individual behaviour issues; 5) Education: It is concerned with the development of different models of curricula for transmitting the new knowledge produced by the project.

Appendix Two: Cultural Biography

by Renee van de Vall, 6 July 2015

The notion of the cultural biography has been adopted by the research project New Strategies in the Conservation of Contemporary Art6 in order to incorporate the changeability of contemporary artworks within conservation theory, and – while recognising the individual characteristics of each single work of art – to serve as a framework to detect similarities and patterns in the dynamics of such works’ development. The notion is derived from the cultural anthropology of things and the study of material culture (Appadurai 1986; Kopytoff 1986; Merrill 1998; Gosden and Marshall 1999; Hoskins 2006; Latour and Lowe 2008). The central ideas of the biographical approach are 1) that the meaning of an object and the effects it has on people and events may change during its existence, due to developments in its physical state, use, and social, cultural and historical context; and 2) that these changes will tend to conform to culturally recognised stages or phases and specific cultures will have different notions of what counts as a successful career for an object.

A major assumption of the New Strategies project was that the typical sequence of biographical phases or stages that are culturally recognised for a traditional work of art, such as first the conception and execution within the artist’s studio, next its leaving the studio and circulation in the art world and finally its acquisition by a public or private collection, is not that easily applicable to contemporary artworks. Our investigations showed that very often ‘leaving the studio’ is an inadequate description of the scattered events and multiple lines of development that contribute to a work’s creation and, very importantly, that works do not cease to change after having been acquired by a museum. Some of our case studies indicated that the default condition of many contemporary artworks is non-existence or at best a kind of ‘half life’ or ‘slumber’ from which they only now and then re-emerge as artworks, and that a major watershed in the life of those artworks being collected by museums is not their acquisition, but their re-installation after (often long) periods of storage (Van de Vall, Hölling, Scholte and Stigter 2011).

Another result of our inquiries was that biographies can be written on many levels: next to that of the artwork as a whole, those of it various components for instance, which can follow different time-lines and show different dynamics. For this reason we found it fruitful to enrich the biographical approach with Latour and Lowe’s notion of the trajectory:

‘A given work of art should be compared not to any isolated locus but to a river’s catchment, complete with its estuaries, its many tributaries, its dramatic rapids, its many meanders and of course with its several hidden sources’.

‘To give a name to this catchment area, we will use the word trajectory’. (Latour and Lowe 2008, 3, 4).

This allows us to endow the work’s biography with a sense of complexity and multiplicity, without losing the normative awareness implied in the idea of the work having a ‘life’.

Members of the Group

Kevin Ashley, Director of the Digital Curation Centre

Luciana Duranti, Chair and Professor of Archival Studies School of Library, Archival, and Information Studies, The University of British Columbia, The Irving K. Barber Learning Centre Director, The InterPARES Project Director

Mark Hedges, Director of the Centre for e-Research, Co-ordinator for Pericles

Anna Henry, Digital Preservation Manager, Tate

John Langdon, Tate Archive, Tate

Pip Laurenson, Head of Collection Care Research, Tate, and Professor of Art Collection and Care, Maastricht University

Barbara Reed, Principle Consultant of Recordkeeping Innovation Pty Ltd.

Vivian van Saaze, Assistant Professor at the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, Maastricht University

Renee van de Vall, Professor of Art and Media, Maastricht University

This report was compiled by Pip Laurenson from transcripts of the recordings from four virtual meetings conducted between April and December 2015.

How to cite: Pip Laurenson, Kevin Ashley, Luciana Duranti, Mark Hedges, Anna Henry, John Langdon, Barbara Reed, Vivian van Saaze and Renee van de Vall, ‘The Lives of Digital Things. A Community of Practice Dialogue’, 2017, https://www.tate.org.uk/about-us/projects/pericles/lives-digital-things.

This report was written within the context of PERICLES, a four-year project (2013–2017) that aims to address the challenges of ensuring that digital content remains accessible in an environment that is subject to continual change. PERICLES has received funding from the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme for research, technological development and demonstration under grant agreement no.601138.