Introduction

Ten Years Alive on the Infinite Plain 1972 is a performance artwork by the US artist Tony Conrad (1940–2016). It combines experiments in visual perception with multiple and layered projections of black and white 16 mm film and with the vibratory effects of close harmonies created by a group of musicians on stringed instruments. By journeying through the fourteen performances of this work since its inception – through the shifting environments and acoustics, the traces of the performances in the memories of those who were involved, and the different forms of oral, visual and written documentation about the performances – this essay explores where and how changes and interpretations have been made to Ten Years Alive on the Infinite Plain since 1972. Divergences and repetitions in the performance of the work are placed in art historical, curatorial, filmic, musical and sound-based contexts as well as in relation to relevant theoretical concepts.

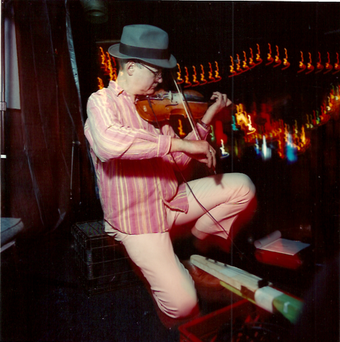

This text comes out of research undertaken at Tate to help support the acquisition of Ten Years Alive on the Infinite Plain (hereafter Ten Years Alive), which has recently been acquired for the Tate collection along with another work by Conrad, Loose Connection 1972/2011. The research has been collaborative, involving the project team for the Andrew W. Mellon-funded research project Reshaping the Collectible: When Artworks Live in the Museum; individuals from a range of departments and practices across Tate (Curatorial, Time-Based Media Conservation, Registrars and Collections Management, Archives and Records Management, and Art Handling and Technicians); and collaborators of Conrad’s, both those who were new to the work and those who were familiar with his practice.1 The reason for taking this collaborative approach was in part to reflect the way Conrad worked, performed and taught, and partly to consider the possibilities and ramifications of collecting this performance work without the artist. For most of its life, Ten Years Alive had the creator at its centre, playing violin, often in brightly coloured t-shirts, often speaking to and entertaining the audience. But Conrad passed away in 2016, and the work has come into the Tate collection abstracted from the body of the artist. Collecting the work with decisions about its future life in the collection being agreed not by the artist but by a collective of people inside and outside of the museum is a shift in the approach Tate would normally take. As a result of this process, I ask: can (and has) the authority of the work now become collectively shared, or is this authority fully transferred to Tate?

On each occasion that it was performed, as we will see, Ten Years Alive was not simply shaped by an exhibition curator who instigated the performance. The moment of each performance encompassed the individuals who invited Conrad to perform; those who made decisions about the way it was performed along with Conrad and others; those who placed the performance into a programmatic context and mediated it for audiences; and those who performed and documented it. This involved festival curators and directors, facilitators, documentary technologies, people working in commercial galleries, producers, sound engineers, and now conservators. Because of these various roles and practices, in this paper I follow curator Maria Lind in suggesting that we think of curatorial practice not as something singular but in its expanded sense as ‘a way of thinking in terms of interconnections: linking objects, images, processes, people, locations, histories, discourses in physical space like an active catalyst, generating twists, turns and tensions’.2

Collecting can form part of this expanded curatorial activity. It involves selection, conceptual and practical decision making, care in its multiple facets, shifts in the degree of authority and authorship. It is a dispersed and shared activity, but this is often not the narrative we hear. The cultural theorist and social scientist Vivian van Saaze has argued that in art history and aesthetic readings we more often get a construction of authenticity and originality through the singular when instead we could see authenticity as something that is ‘done’ and ‘constructed in practice’.3 One way to achieve this is by looking at the ‘interaction between the artist and museum professionals’.4 In the conservation of durational and/or time-based works, detailing an artwork’s biography can be a way to inform conservators about its core principles and its variability. The study of an artwork’s biography in a collection also helps demonstrate how an artwork is co-produced or collaboratively shaped by museum practices.5 Taking the example of Ten Years Alive, although the performance was conceived by Conrad, it has clearly been and will continue to be co-shaped or co-produced by the variety of people, spaces, conditions and practices who were (and will be) involved in its future realisations. This includes the work of conservators, curators and registrars at Tate as well as individuals from the communities of practice outside the institution that surround the performance, the artist, and the forms and styles of musical practice and performance found in Ten Years Alive. 6

We learn about these practices and perspectives by listening to and sometimes recording embodied knowledges and experiences and, as performance art theorist Rebecca Schneider describes, by drawing attention to the ‘basic repetitions that mark performance as indiscreet, non-original, relentlessly citational and remaining’.7 As part of this, it is also important to take account of our own embodied experiences as researchers. The questioning of the singular, original and ‘mythic’ that can come from acknowledging shared production, labour and collaboration at times sits in contradiction to the modernist, canonising project of the museum and of art history – fields that are always entangled with economics and market forces. At other times, these contradictions are part of the same processes. Scholar Fernando Domínguez Rubio, for example, has explored how the elements of an ‘artwork’s particular biography’ in a museum – notes, documentation, contracts, the history of the work – act to stabilise ‘the artwork’s identity by providing standards and criteria for authentic repetition’.8 An artwork in a collection is ‘inseparable from its constituency’, and because of this, caring for an art object in the collection is not just about physical care but also about ‘preserving the components of its constituencies’.9 These contradictory drives, the canonising of art history, the stabilising effect of the museum and the diverse repetitions and perspectives are present in this essay and in this case study as a whole. By bringing them together rather than following one or the other I hope to explore how the changes, differences and interpretations of Ten Years Alive since 1972 have been made not just by Conrad but by those who performed in it, by the site-specificity of galleries and spaces it was performed in and by the wider social and political contexts within which it took place, as well as examining the role of media, sound, film, bodies and technologies in performing, documenting and mediating the performance.

Beginning in the present

In the mid-2000s there was a resurgence of interest in Conrad’s work in the visual arts, which led the artist to look back over his career and revisit past ideas and performances.10 On one of these occasions, in a 2009 interview for Frieze magazine, musician and collaborator David Grubbs asked Conrad whether his ‘back story’ ever felt like a burden. Conrad responded, ‘To start at the end and look back is a good way to do it. We’re always at the end.’11 This comment brings to light his preoccupation with the present and the live moment of a performance. It is also a reminder of the kind of music he created at this time in the early 1970s, which had an emphasis on duration, sustained tones and ‘just intonation’.12 Conrad was interested in creating an experience that would be ‘subjectively transformed’ rather than structured by ‘rational clock-time’.13 Describing this to Grubbs, he frames the present in a similar way to philosopher Walter Benjamin’s angel of history, where the present is not the starting but the end point, the moment of death (a contradiction that is present in Conrad’s work in the idea of ‘living’ on the infinite plain).14 When Conrad reflected on his work it was done in this recursive way. Instead of thinking about a linear chronology, Conrad drew on connections and patterns; he wrote, spoke and thought about these patterns in relation to shifts in political, cultural and social situations.

I have chosen to echo Conrad’s emphasis on the recursive structure as well as on the ending, or death, as the moment of beginning, one that marks the beginning of research into Conrad’s work at Tate and the moment of abstraction from Conrad’s physical body. I begin with the proposal to acquire Ten Years Alive and the moment it was performed in The Tanks at Tate Modern in 2017. I then jump back in time to the first performance at The Kitchen in 1972. From there I pull out three moments; the mid-1990s performances at the Empty Bottle in Chicago and the Showplace Theatre in Buffalo; performances between 2004 and 2007 in arts, music, film festivals and galleries; and finally, its journey into Tate via the Live Arts Festival in Bologna in 2013 and the most recent performance at Tate Liverpool in 2019. These iterations are mediated by watching, looking at and reading the available documentation and by drawing on existing and new interviews with the performers of Ten Years Alive and Conrad’s collaborators, which were undertaken prior to and for the project. I use this archival and ethnographic material to make visible where changes appear to have been made by individuals, technologies, environments and through performances, and then reflect on the extent to which these have a relationship with particular trends in curatorial practice. By exploring what changed and what remained consistent or sticky in Ten Years Alive, we can consider how the performance might have been reshaped in relation to curatorial practice in its expanded sense, and in relation to performance histories, festivals and conservation. This approach is not nostalgic, seeking the original moment as the most authentic, but rather, to use the words of Rebecca Schneider, it looks at how the ‘performance remains differently’ and how the performance becomes itself ‘through messy and eruptive reappearances’.15

Before moving on, I want to acknowledge the gaps in our research. Some individuals were interviewed and not others, and while for some of the performances we have many reflections, for others we have just a few or none at all.16 These gaps, which include an absence of responses from the people watching performances (apart from selected reviews), are important because of the way they ‘may influence practice’.17 Although the Reshaping the Collectible project has been about making the invisible visible, such absences perhaps demonstrate the habit of museums like Tate to give authority to certain individuals and practices while other voices remain unacknowledged.

The Tanks, Tate Modern, London, 2017

In 2015, Andrea Lissoni (Senior Curator at Tate) and Vera Alemani (Gallerist, Greene Naftali) visited Tony Conrad at his studio in Buffalo, New York. In a conversation that focused on the performance of Ten Years Alive as well as the artist’s relationship to minimalism, Lissoni raised the idea of bringing the performance into Tate’s collection. Conrad responded, ‘but how can it be live and collectable?’. Throughout the conversation Conrad appears to have seen this as something that could be worked out.18 He passed away the following year and commemorative projects, exhibitions and memorial events followed.19 At Tate, the ambition to bring this work into the collection continued to be progressed by Lissoni and Carly Whitefield (Assistant Curator). Lissoni recruited the engagement of the Time-Based Media Conservation department and Collection Care Research to support the acquisition and a proposed performance of the work in 2017.20 At this moment the performance began to be co-shaped by the museum and some of Conrad’s collaborators (referred to from 2017 onwards as ‘transmitters’). This research around the acquisition and performance led to the nomination of this work for the research project Reshaping the Collectible.

Tony Conrad Ten Years Alive on the Infinite Plain 1972 (c) Tate

There has never been a score for the performance of Ten Years Live; there are also no definitive written instructions. Instead, each time it has been shown, Conrad taught the work to new performers (or reminded those who had performed it in the past). With the work coming into the Tate collection but the artist no longer alive to give instructions or clarify how the work should be performed, it was clear that decisions would need to be made based on its history and by listening to the experiences of people who had performed and worked with Conrad in the past. It seemed this would be fitting for the work and his practice, which from the start had challenged authorship (while retaining a sense of authority and control), had surfaced out of collaboration and, over its history, had involved various communities of practice. It was therefore decided by Tate curators and Conrad’s estate that people who had performed with Conrad in the past and those who were close to him, personally and professionally, would be invited to discuss with Tate-based conservators, curators, technicians and researchers how a sense of liveness and variation could be retained as the work moved into the collection. Their research and discussions led to the performance Fifty-Five Years on the Infinite Plain in The Tanks at Tate Modern in January 2017 (fig.1). In the work’s original title from 1972, the ‘ten years’ referenced the previous decade that Conrad had spent working on minimalist music, which began in 1962 when he started to collaborate with musicians La Monte Young, John Cale, Angus MacLise and Marian Zazeela. The title was updated to Forty-Five Years on the Infinite Plain for the 2007 performances in Brussels and Berlin, and in doing so Conrad maintained the temporal relationship with the year 1962; this convention was observed again for the Tate performance in 2017, Fifty-Five Years on the Infinite Plain.21 In the large, cavernous, oil-scented environment of The Tanks, the performance was situated within live art practice and the contemporary art museum.

On this occasion, with Conrad no longer living, his part was played by a recording of his violin taken from an earlier performance, with Rhys Chatham playing the ‘long string instrument’ or ‘long string drone’ invented by Conrad,22 Angharad Davies on violin and Dominic Lash on bass.23 Andrew Lampert (who had restored Conrad’s work for Anthology Film Archives) performed the projections. Apart from Lash, all of these individuals had performed this work with Conrad in the past. Interviews were recorded with these performers and other collaborators before and after the event, with the idea that they would help the future conservation of the work and bring an understanding of how it could be performed and interpreted in the future.24 The interviews also reflected on a future, more permanent display of the performance in the collection galleries that would be called Elements of Ten Years Alive on the Infinite Plain.25 In the end it was decided that this display version would not be realised or accessioned, since individual elements might take on the status of artworks; there were also concerns that the display version might be shown instead of a performance. But during this moment when the work began to come into Tate’s collection, the collaborations that were initiated, the questions that were raised in the interviews, and the ideas of how it might sit and be shown in the collection set a frame for the development of further research at Tate. Although they were concerned with how the work might live and unfold in the collection, therefore enabling it to change over time, these recorded conversations also acted to fix certain perspectives around ‘the work’ which ultimately guided but also limited the way Ten Years Alive eventually came to Tate.

The Kitchen, New York, 1972

Fig.2

Ben Tatti

Electronic Imagery 1972, installation at The Kitchen, New York, 18 May 1972

Steina and Woody Vasulka Fonds, Daniel Langlois Foundation Collection, Montreal

On 11 March 1972, Rhys Chatham, Tony Conrad, Laurie Spiegel and Woody Vasulka performed Ten Years Alive on the Infinite Plain at The Kitchen in New York, a space founded in 1971 by Steina and Woody Vasulka for experimental artists and composers. There is no visual documentation of this performance. A photograph of Ben Tatti’s video installation Electronic Imagery 1972 (fig.2), shown later the same year, gives an idea of the space in which Ten Years Alive was performed. But while visual documentation is lacking, we do have an audio recording made by Conrad, as well as accounts of the performance from Chatham and Conrad.26 On violin, Conrad played microtonal intervals, also known as a ‘Pythagorean comma’, ‘creating acoustic beats’27 or a drone sound. Accompanying Conrad’s violin was a series of glissandos played on the long string instrument by Chatham – a nineteen-year-old who at the time ran The Kitchen’s music programme. Spiegel provided a ‘boom, boom, boom, boom, boom, boom, boom, boom-boom, boom’28 beat by repeatedly strumming the same note on a one-stringed bass guitar that Conrad had modified and provided.29 From Chatham we gather that the musicians sat in the centre of the room with the audience surrounding them. For over an hour and a half the musicians played together following instructions by Conrad. Video monitors were located on the walls of The Kitchen screening experiments in video imaging by the Vasulkas.30 On the evening of the performance they were ‘improvise[d]’ by Woody Vasulka.31

This description of video monitors is not how we recognise the work today. Although the idea of using projections was conceived at the time, it was in fact only realised in public with the 1996 performance at Yttrium Festival in Chicago, run by Table of the Elements, a label that had been reissuing music by Conrad since 1993.32 Conrad retrospectively wrote about his plan in 1972 to have a video transmission that would echo the movement between microtones in minimalist music and in mathematics, via the generation of ‘exclusive or’ – a binary logic used in Boolean algebra:

Was it possible, I wondered, that video signals might be combined to form such an algorithm, generating an EXCLUSIVE OR effect in real time? I brought this issue to The Kitchen, where the Vasulkas had an impressive array of video effects generators. Using a film image of stripes as source material, I wanted to generate a checkerboard pattern by combining the signals from two cameras, one vertical and the other horizontal. However, none of the various ‘recipes’ (such as the above) I had composed for EXCLUSIVE OR was achievable with the particular combination of equipment available. We finally settled on a substitute set of logic functions, and the performance went ahead without EXCLUSIVE OR.33

Conrad’s emphasis on the ‘exclusive or’ is evidence of his mathematical education.34 This binary logic, ‘which is the same binary logic used in computers’, was a concept Conrad explored in his film work, writing and music35 .In Ten Years Alive he intended to explore this mathematical proposition by creating striped patterns in positive/negative film and by combining this with sustained tone. The source material he refers to is a fragment from his work with the filmmaker and actor Beverly Grant called Straight and Narrow 1970, a film of black and white horizontal and vertical stripes accompanied by a percussive musical soundtrack.36 Before the performance at The Kitchen, Conrad tested out his idea of binary logic and video transmission with the Vasulkas, but without success. They became ‘frustrated’ with the lack of available ‘binary video tools’ and found an alternative solution for the event.37 It was not until the mid-1990s, when Ten Years Alive was revisited, that 16 mm projections were used in the performances, and so although the visual side to the work was in some ways conceptualised in 1972 (a continuity stressed by Conrad in his interviews and writing), it only gained consistent shape through later public performances.38

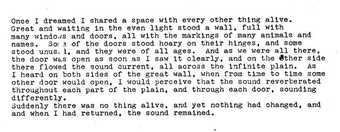

Fig.3

An excerpt from a 1972 poem by Tony Conrad that was used for the press announcement for the performance of Ten Years Alive at The Kitchen, New York, 1972

Vasulka Archive