- Artist

- John Latham 1921–2006

- Medium

- Books, plaster, metal, light bulb and paint on canvas on board

- Dimensions

- Displayed: 1225 × 965 × 280 mm, 18kg

- Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Purchased 2004

- Reference

- T11841

Summary

Belief System is a wall-mounted assemblage collaged onto a painted canvas. Its main feature is a group of books and disparate metal elements embedded in plaster that was poured onto the canvas when it was in a horizontal position. Latham sprayed this composite cluster with black paint, unifying it and making it stand out from the white background. Two pairs of antique books stand face to face, their pages interleaved, blending them into single objects. The hard leather covers of the lower pair touch at the edges, resulting in an object which appears square and enclosed when seen hanging in the vertical position. The covers of the other pair of books, which is in a configuration at right angles to the first pair, are held open. Those of the lower book are folded right back revealing ripped paper and a title page bearing the words ‘The Parisians’ on one side. On the other, partially visible, a nineteenth century engraving shows a woman sitting on a grassy bank with a man at her feet. Smaller books are stuck to the covers of the four bigger books in varying positions. All the books are warped and deformed by burning and spraying. Such fragments of metal implements as a tin opener, a spring, a coil of wire, a small light bulb, sections of wire gauze, a comb and a long screw are attached to the book covers or lie in the plaster on the canvas. On the left side of the painting a length of cable, painted silver, extends out of a hole down towards the congealed assemblage into which it disappears. It is balanced in the composition by a wavy length of wire describing an arc on the right of the group of books. At the top of the canvas a solitary book is held in place with more plaster, sprayed black and silver at the base where it is wrapped with a length of wire gauze.

Belief System is one of a series of four similar works Latham made in 1959 with the same title. The works share a common structure with other paintings of the period, whose titles – The Bible and Voltaire 1959, The How and the Why 1959, Omniscientist

1963 – refer to the philosophical and scientific systems that the artist was seeking to undermine. Books have a special significance in Latham’s work as a source of knowledge as well as of error. He referred to them as ‘Skoob’, the reversal of the word representing the reversal he aimed to effect on all they represented. His use of them in his assemblages of the late 1950s and early 1960s emphasises their dual status as physical objects held in a static state, witnesses of an event taking place in the present – their visual apprehension by a viewer – and repositories of knowledge, invoking a linear temporality in the reading of them. Like human bodies, they exist concurrently as unified wholes and as the containers of a mass of information, invoking spaces or concepts far beyond the immediate matter they are composed of.

Born in northern Rhodesia (now Zambia), Latham studied painting at Chelsea School of Art (1947-51). He was deeply influenced by the work of El Greco (1541-1614) which he discovered on a visit to Rome in 1945. He created dark-toned quasi-allegorical oil paintings until, on a revelatory day in October 1954 (referred to in his later writings as ‘Io54’ or ‘Idiom of 1954’), he used a spray gun filled with black paint to make his first ‘process sculpture’. In the dense black area of sprayed paint, composed of millions of tiny dots of pigment, Latham saw a new way of understanding time and matter through a unifying atemporality. He later used this in a series of One Second Drawings (see Tate T02070), in which he sprayed sixty boards for one second each with black acrylic paint. The action embodies the idea of what he called a ‘least event’, the very action of making elementary marks in an empty space (on a blank white board) manifesting itself as an elemental structure. The individual dots making up areas of sprayed paint have a similiar structural function to the letters making up the contents of a book. In his first wall-relief assemblage using books, Burial of Count Orgaz 1958 (Tate T02069), books echo the draped fabric in El Greco’s original painting. In the Belief System works, as in a similar series made during the same period titled Observer made in 1959-60 (see Observer IV Tate T03706), books embody processes of thinking contained within an all-embracing present. In another work from the same period, Film Star 1960 (Tate T00854), the open books pages of books are painted twelve colours. Latham filmed static shots of the pages open on different colours to make his film Unedited Material from the Star (1960) in which the books appear to change colour as they open and close. Latham believed the purpose of art is to recreate the lost relationship between the individual and the whole. To this end, he emphasised time-based process, or a language of events, over the static object.

Further reading:

John Latham: Art after Physics, exhibition catalogue, Museum of Modern Art, Oxford and Staatsgalerie Stuttgart 1991, pp.14 and 16

John Latham: In Focus, exhibition brochure, Tate Britain, London 2005, [p.6], fig.5 reproduced [p.6] in colour

John Latham: Zeit und Schicksal, exhibition catalogue, Städtische Kunsthalle Düsseldorf 1975, pp.29 and 31

Elizabeth Manchester

March 2006

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Display caption

Here, books represent systems of knowledge that John Latham wanted to undermine. He referred to his body of work made using books as ‘Skoob’. Turning ‘books’ backwards represented his aim of overturning their authority. Latham staged ‘Skoob Tower Ceremonies’ as part of the Destruction in Art Symposium. These controversial performances involved setting light to columns of books in front of places with institutional power and knowledge, such as the British Museum.

Gallery label, May 2023

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Explore

- abstraction(8,615)

-

- non-representational(6,161)

-

- gestural(891)

- irregular forms(2,007)

- monochromatic(722)

- emotions and human qualities(5,345)

-

- wisdom(19)

- defacement(257)

- texture(466)

- reading, writing, printed matter(5,159)

-

- book - non-specific(1,954)

- wire(19)

You might like

-

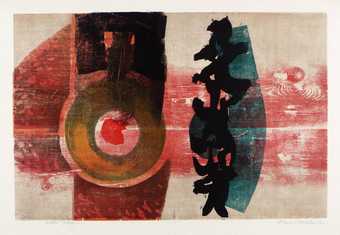

Michael Rothenstein Black and Orange

1961 -

Robert Medley A Tree Study

1959 -

Bernard Cohen In That Moment

1965 -

John Latham Film Star

1960 -

William Turnbull No. 1 1959

1958–9 -

William Turnbull No. 7 1959

1959 -

Nigel Henderson Collage

1949 -

John Latham Burial of Count Orgaz

1958 -

John Latham One-Second Drawing (17” 2002) (Time Signature 5:1)

1972 -

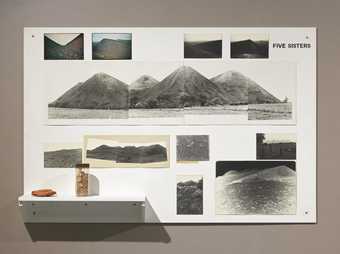

John Latham Derelict Land Art: Five Sisters

1976 -

John Latham Observer IV

1960 -

John Latham Man Caught Up with a Yellow Object

1954 -

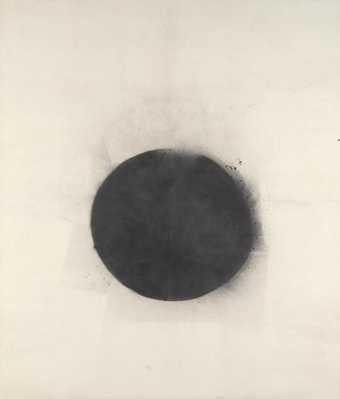

John Latham Full Stop

1961 -

John Latham Time-Base Roller

1972 -

Janet Nathan Zeloso

1979