Iconic landmarks: as you've never seen them before

Many artists have painted, drawn or photographed well-known landmarks in their art. But although the places they depict are famous, we may not immediately recognise them. Find out how artists have used colour, texture, shape and unexpected viewpoints to make us see these landmarks in a new way.

John Piper is known for his richly textured depictions of British landscapes and architecture. But for this painting he ventured further afield – to Rome. The details of The Forum’s architecture are left vague, but a strong impression of it is created through the arrangement of geometric shapes and varied textures, combined with the warm bright colours of the Roman light.

John Piper

The Forum

(1961)

Tate

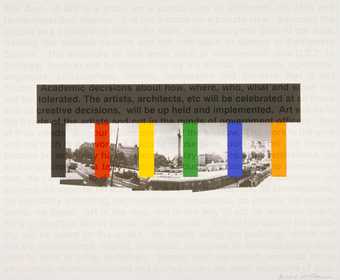

Rather than capturing the grandeur of Trafalgar Square, Ceri Richards decided to highlight other aspects of its character. People, paving stones, pigeons and fountains become a lively blur in his first version of the London landmark. Ten years later he used the shapes and colours of Trafalgar Square to create an abstract version of it.

Ceri Richards

Trafalgar Square, London

(1950)

Tate

Ceri Richards

Trafalgar Square (trial proof)

(1962)

Tate

© The estate of Ceri Richards. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2023

Robert Delaunay abstracted a famous French monument in this view from his window. (Can you make out what it is?). While Catherine Yass manipulates photographic film and presents us with unfamiliar takes on architectural spaces. This is a photograph she took of Tate’s Modern’s Turbine Hall. Her technique involves taking two photographs of the same scene – one a colour positive transparency and the second a negative transparency. The two images are then combined to produce the final work. What other ways could you use photography or image editing software to distort or enhance the appearance of places?

Catherine Yass

Bankside: Cherrypicker

(2000)

Tate

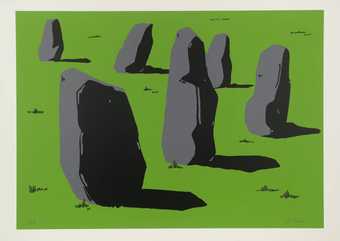

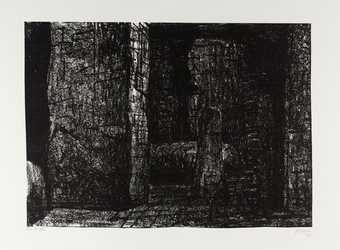

In a series of works based on Stonehenge, Henry Moore focuses right in on details of the monument recreating it as a series of abstract shapes… These become as mysterious as the monument itself.

Henry Moore OM, CH

Stonehenge XII

(1973)

Tate

In 1995 artists Christo and Jeanne-Claude presented the Reichstag, (one of Berlin’s best known landmarks), in a way that it has never been seen before (and is unlikely ever to be seen again!) They covered it with 100,000 square metres of billowing silver-grey fabric, tied down by over fifteen kilometres of blue ropes. By wrapping the building they emphasized its form and bulk and the shapes of its architectural features (as well as adding sense of mystery to it, like an unopened present!). Watch this video to find out more about their process and the ideas behind Wrapped Reichstag.

This film file is broken and is being removed. Sorry for any inconvenience this causes.

Artworks aren’t the only pictures that landmarks feature in!

From the ordinary, to the extraordinary

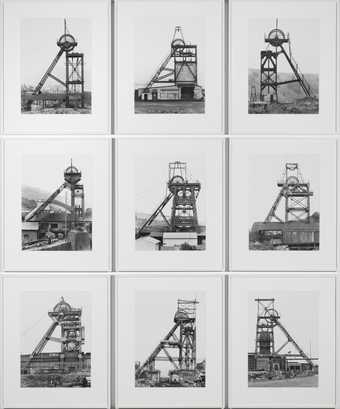

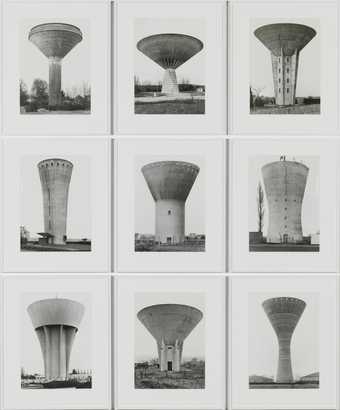

Landmarks don’t have to be famous buildings. Conceptual photographers Hilla and Bernd Becher, photographed the type of industrial building that we might pass every day without a second glance. But the Bechers saw beauty in the functionality of the design of these structures and their impressive monumentality. In their photographs the buildings become landmarks. They photographed each building in exactly the same way: always on cloudy days (so there were no shadows), and always from the same angles. They then made groups of photographs that showed the same type of structure. By doing this they created a pattern of shapes and forms. Hilla talked about the rhythm created by these groupings:

By placing several cooling towers side by side something happened, something like tonal music; you don’t see what makes the objects different until you bring them together, so subtle are their differences.

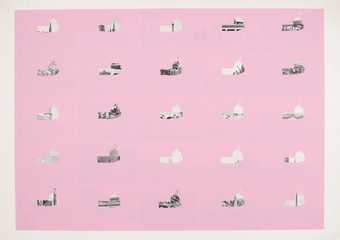

Bernd Becher and Hilla Becher

Winding Towers (Britain)

(1966–97)

Tate

Bernd Becher and Hilla Becher

Water Towers

(1972–2009)

Tate

Bernd Becher and Hilla Becher

Gas Tanks

(1965–2009)

Tate

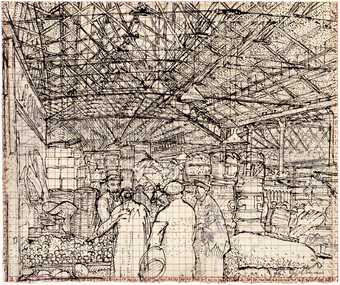

Other places that you might think of as ordinary can become extraordinary in art. Harold Gilman drew the interior of Leeds Market and created an iconic artwork from its structure and sense of space.

Harold Gilman

Study for ‘Leeds Market’

(c.1913)

Tate

Ed Ruscha often uses ordinary – even boring – subjects like petrol stations or car parks as the subject for his photobooks. For his Sunset Strip Portfolio series, he photographed all the ordinary (and pretty shabby) buildings along the Los Angeles’ street. He created an iconic and fascinating record of what the street looked like at that moment in time, way before Google Street View! Watch this video to find out what drew him to these distinctly non-impressive landmarks:

This film file is broken and is being removed. Sorry for any inconvenience this causes.

Public sculpture

Landmarks don’t just feature in art as a subject. Art itself can be a landmark. Art that is made for public places is called public art. Artists who make public art respond to the place they are making it for – this approach is referred to as site-specific. Anthony Gormley’s Angel of the North, is a huge public landmark in the North East of England. For Gormley, the location of the sculpture was important: it pays tribute to the coal miners who worked the site where the Angel now stands, and it also reflects the transition from an industrial to information age. This is an earlier (and smaller) sculpture by Gormley that he based his Angel of the North on.

Sir Antony Gormley OBE RA

A Case for an Angel III

(1990)

Tate

Sculptors Barbara Hepworth and Henry Moore used natural shapes and forms in the landscape (such as hills, rocks and clumps of trees) to inspire the forms of their public sculptures. In this way, they reflected the environments in which they were located.

Henry Moore OM, CH

Three Piece Reclining Figure No.1

(1961–2, cast date unknown)

Tate

Dame Barbara Hepworth

Conversation with Magic Stones

(1973)

Tate

Find out more about Henry Moore’s sculpture and inspiration in this resource.

Rachel Whiteread

Untitled (House) 1993

Commissioned by Artangel, sponsored by Becks. Courtesy Gagosian Gallery © The artist. Photo: Sue Ormerod

Not all public sculptures are permanent. In 1993 Rachel Whiteread cast in concrete a whole house that was due to be demolished. She did this by spraying liquid concrete into the interior of the house and then removing the external walls. The domestic became public. Her sculpture emotively fossilised the memories and experiences that are associated with the fabric of our homes. Despite calls to preserve the house as a public artwork, it was destroyed in 1994.

Land art modern and ancient

‘Landmark’ could also be interpreted as a mark on the land. Land art is art that is made directly in the landscape, sculpting the land itself into earthworks or making structures in the landscape using natural materials. Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty 1970, is built entirely of mud, salt crystals, basalt rocks and water. It forms a 460 metre long spiral jutting out from the shore of the Great Salt Lake in Utah, USA.

Robert Smithson

spiral Jetty April 1970, Great Salt Lake, Utah

Black rock, salt crystals, earth, red water (algae)

3½ X 15 X 1500 feet

© Estate of Robert Smithson / licensed by VAGA, New York, NY; Collection: DIA Center for the Arts, New York

Photograph: Gianfranco Gorgoni

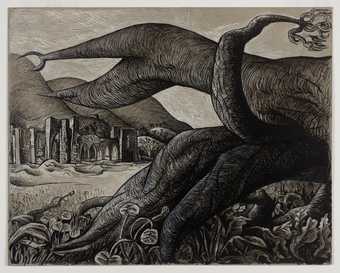

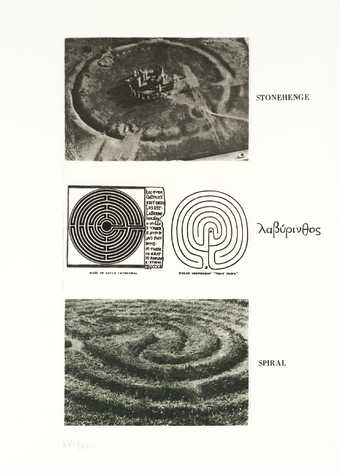

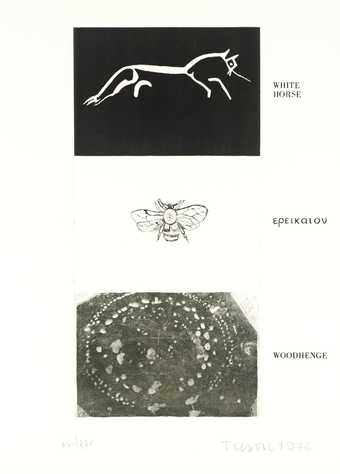

Smithson’s Jetty is a huge and impressive monument reminiscent of ancient earthworks and the chalk drawings ancient people etched in the landscape. No one really knows what they mean or what they were for but their powerful impressive shapes and forms have a mystical value that still intrigues us today. Artist Joe Tilson explores their shapes and forms, and possible meanings in his work:

Joe Tilson

[no title]

(1976–7)

Tate

Joe Tilson

[no title]

(1976–7)

Tate

Land artist Richard Long used these ancient landmarks to inspire his own work, too. For Connemara Sculpture he recreates the shape of an ancient labyrinth dating from 2000 BC using white pebbles to form his own drawing in the Irish landscape. Other land artworks by the artist include lines made by walking backwards and forwards flattening the grass in a field; and moving rocks, stones and turf to create shapes.

Street art

Street art adds ‘marks’ to urban landscapes. Street artworks, though not always officially sanctioned often become iconic landmarks, too.

In 2008, six internationally acclaimed street artist were invited to create works for the walls of Tate Modern and the streets around the gallery.

In November 2015 street art collective Drips And Runs were challenged by Tate Collective London to produce a collaborative mural (in only 3 hours!) inspired by their experience of The World Goes Pop at Tate Modern. Find out what happened.

More than just a landmark

Monuments are landmarks often created to remember people, celebrate triumphant battles or commemorate terrible events. Artists sometimes use the idea of a monument to express their feelings or draw attention to social or political events or concerns.

In 1952 an international competition was announced to design a monument to pay tribute to people imprisoned or killed for their political beliefs. Several artists presented designs and Reg Butler’s design was chosen as the winner. Sculptors often use maquettes (small-scale models) to prototype larger pieces:

Reg Butler

Working Model for ‘The Unknown Political Prisoner’

(1955–6)

Tate

Dame Barbara Hepworth

Maquette for ‘The Unknown Political Prisoner’

(1952)

Tate

Keith Coventry creates a very different kind of monument. Trees like Keith Coventry’s casts can be found growing out of the concrete pavements of many shopping centres or public housing estates. The broken, stunted trunks are remnants of an act of vandalism; recalling trees that are no longer there. By making monument-like sculptures from these damaged fragments of public spaces into an art gallery, Coventry highlights the gap between the vision of the ideal of homes for everyone and the reality of the urban experience. He also explores the gaps between natural and built environments.

Photographer Guy Tillim photographs landmarks to create a photographic monument to Congolese Independence leader Patrice Lumumba (1925–61). In 2006 Tillim photographed places across Africa named after Lumumba. His photographs show the remains of colonial architecture, derelict buildings, the remnants of a grandiose hotel, residential buildings or administrative offices. Some are conventional landmarks, some are not, but they all become landmarks to Tillim as they are linked together by the symbol of Lumumba and so share a common history. Although not actually portraying Patrice Lumumba, they evoke the symbol he stands for, Congo’s struggle for independence against colonialism, the symbol of a free Africa.

Guy Tillim

Grande Hotel, Beira, Mozambique

(2008)

Tate

HAVE A GO!

We’ve pulled together some thoughts to help you get started researching landmarks as a theme:

- Think of ways you could use colours, textures or shapes to explore a building or place. Or look for interesting details or unusual angles. Try and capture your impressions of it or how it makes you feel – rather than just what it looks like.

- Have a go at creating your own land art landmark. Use rocks or stones to build a small structure or create lines and shapes with twigs or coloured leaves. What is it you like about the landscape where your land art will be placed? Plan and record your land art using sketches, notes or photographs. (Find out more about land art in Tate’s glossary).

- Design your own monument to something that matters to you. This could be an important event or something you feel strongly about. Makes sketches and a maquette for your monument. Or, like Tillim, make a photographic monument to someone or something that you would like to remember of draw attention to