Not on display

- Artist

- Emily Kame Kngwarreye 1910–1996

- Medium

- Acrylic paint on canvas

- Dimensions

- Support: 918 × 610 mm

frame: 1085 × 775 × 70 mm - Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Purchased with funds provided by Lady Sarah Atcherley in honour of Simon Mordant 2019

- Reference

- T15135

Summary

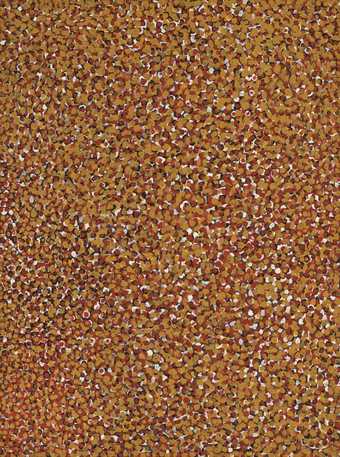

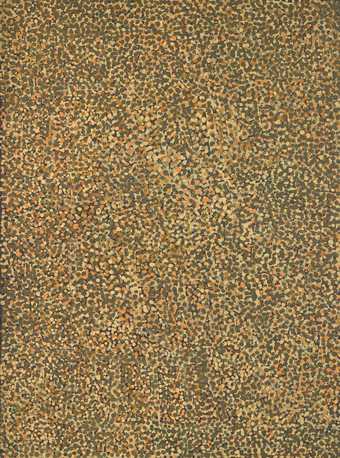

Untitled 1990 is an acrylic painting on linen that consists of mostly white linear structures and white, red and blue dots on a blue-grey background. These dots are comparatively large and less densely painted than in some of Kngwarreye’s other paintings, such as Untitled (Alhalkere) 1989 (Tate T15133) and Endunga 1990 (Tate T15134). The linear element is also more prominent in this work, pre-empting the artist’s later paintings that consisted of bold horizontal and vertical stripes rather than dots. These lines are based on natural elements from the artist’s native landscape in Australia, including the lines of plants and trees, but also underground yam roots and emu tracks that are not always so clearly visible.

Kngwarreye began to paint with acrylic in late 1988, when she was already in her seventies, and between then and her death in 1996 she created over 3,000 paintings. Prior to this she made batik-based fabric works, starting in 1977 when a workshop was set up as part of women’s adult education courses in her native community in the Alhalkere land of the Utopia region, 270 kilometres north-east of Alice Springs, in the Northern Territory of Australia. Kngwarreye’s paintings are formally abstract, consisting of dots, lines or coloured fields. Her work was inspired by her cultural life as an Anmatyerre elder, and her lifelong custodianship of the women’s Dreaming sites in her clan country of Alhalkere. Seemingly abstract dots and lines in her work often resemble the vegetation, animals and landscape of the country as well as her ancestral stories. As with other contemporary Aboriginal art in Australia, Kngwarreye’s work is closely connected with contemporary issues surrounding identity and land right within a post-colonial condition, while also sharing formal affinities with abstract modern art movements.

In paintings such as Untitled 1990, Kngwarreye painted on unstretched linen laid flat on the ground, in a similar manner that she would also make traditional sand paintings for women’s ceremonies in her community. The location of Alhalkere, also known as ‘Alalgura’, is central in Kngwarreye’s imagery. The ‘dots within dots’ style is characteristic of her work, representing plant seeds that are native to her land, while also seemingly abstract. The artist also chose colours that stem from nature and her community surroundings, often chiming with the seasons. Dots are widely used in Australian aboriginal art, in particular by artists in Papanya Tula, an area in the Western Desert, but Kngwarreye’s dot paintings such as this one are distinctive in their non-figurative composition and lack of direct connection to the creation stories or ‘Dreamings’ commonly found in aboriginal art. The four edges of the painting, where they wrap round the stretcher, are painted in short brown and black stripes that are similar to the body-painting lines used in Anmatyerre women’s ceremonies, in which Kngwarreye was a key elder. They also often indicate rivers and the terrain of the community’s landscape.

A closer examination of the Alhalkere landscape reveals that Kngwarreye’s paintings are surprisingly accurate depictions of actual surroundings, originating in her deep understanding of the land as a complex link between places and people that contains traces and memories of the past, present and even future, a unique notion of time that indigenous people describe as ‘everywhen’. Her works are therefore simultaneously abstract and representational. In a rare interview in 1990 with Rodney Gooch, a long-time manager of Central Australian Aboriginal Media Association (CAAMA) that facilitated the sales of artworks from the Utopia including hers, Kngwarreye talked about her imagery: ‘Whole lot, that’s whole lot, Awelye (my Dreaming), Arlatyeye (pencil yam), Arkerrthe (mountain devil lizard), Ntange (grass seed), Tingu (Dreamtime pup), Ankerre (emu), Intekwe (favourite food of emus, a small plant), Atnwerle (green bean), and Kame (yam seed). That’s what I paint, whole lot.’ (Translated by Kathleen Petyarre, in M. Boutler 1991, p.61.) In other words, rather than being descriptive of elements of a landscape, her paintings could be understood as encapsulating a totality of the conditions of her identity and life. Throughout her prolific artistic career, Kngwarreye continued to document and interact with her land, and played a seminal role in preserving its integrity in accordance with her ancestral journeys.

Further reading

Margo Neale, Emily Kame Kngwarreye: Alhalkere: Paintings from Utopia, exhibition catalogue, Queensland Art Gallery, Brisbane 1998.

Michael Boulter, The Art of Utopia: A New Direction in Contemporary Aboriginal Art, Sydney 1991.

Sook-Kyung Lee

September 2018

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Display caption

The dots in this painting are larger and less densely spread than in many of Kngwarreye’s works from this period. She developed a more prominent linear style in her later artworks. These linear patterns can indicate lines of plants and trees, but also less identifiable features such as underground yam roots and emu tracks. Like maps, they reveal the connection between places, people and all things. As an Anmatyerre Elder, Kngwarreye’s paintings depict her deep understanding of the land, and its traces and memories of the past, present and future.

Gallery label, July 2021

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

You might like

-

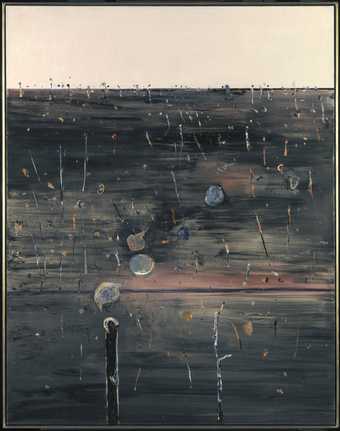

Fred Williams Burnt Landscape II (Bushfire Series)

1970 -

Fred Williams Dry Creek Bed, Werribee Gorge I

1977 -

Fred Williams Riverbed D

1981 -

Simon Linke Remembering Marcel 1987

1988 -

Gordon Bennett Possession Island (Abstraction)

1991 -

Emily Kame Kngwarreye Untitled (Alhalkere)

1989 -

Emily Kame Kngwarreye Endunga

1990 -

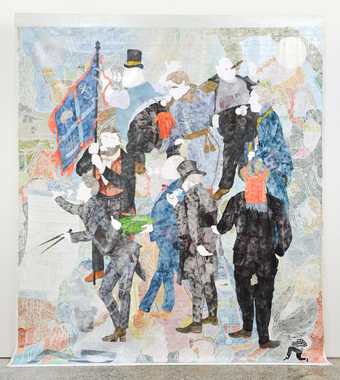

Helen Johnson Bad Debt

2016 -

Helen Johnson Seat of Power

2016 -

Helen Johnson A Feast of Reason and a Flow of Soul

2016 -

Imants Tillers Kangaroo Blank

1988 -

D Harding The Leap/Watershed

2017 -

Judy Watson massacre inlet

1994 -

Judy Watson memory scar, grevillea, mangrove pod (& net)

2020 -

Vivienne Binns The Aftermath and the Ikon of Fear

1984–5