Sorry, no image available

In Tate Britain

- Artist

- Sir Isaac Julien CBE RA born 1960

- Medium

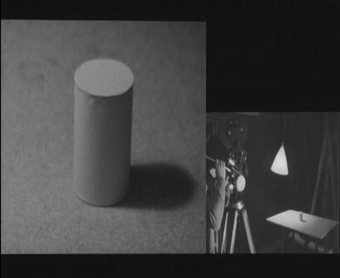

- Film, 16mm, shown as video, black and white, and sound (stereo)

- Dimensions

- Duration: 44min, 29sec

- Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Presented by the artist 2018, accessioned 2023

- Reference

- T16016

Summary

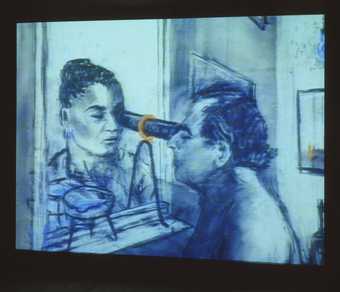

Looking for Langston 1989 is a film shot on black and white film lasting forty six minutes and twenty nine seconds. It begins with a recording of the original radio broadcast made in tribute to the American poet and activist Langston Hughes (1901–1967) upon his death in 1967. Onscreen, whilst the recording is played, a cast of mourners gathers at an imagined version of Hughes’s funeral in which Isaac Julien plays the deceased poet in his coffin. The camera moves to a bar scene with men dressed elegantly in black tie, gathered in a setting somewhere between a 1920s speakeasy and a 1980s club – tenderly partnered up for dancing or just sitting with a drink or a cigarette. The film continues to shift from archive footage to imagined moments in different locations, as well as dream sequences, tracing the relationship between the two leading Black protagonists, a young Hughes played by Ben Ellison and the object of his desire, Beauty, played by Matthew Baidoo. The soundtrack is a mixture of archival recordings of the poetry of Hughes, Richard Bruce Nugent, James Baldwin and Essex Hemphill alongside contemporary 1980s music such as ‘Can You Party’ by Royal House. The dangers of life for a queer person of colour are clearly rendered in the film, which ends with a raid on the club by a mob of ‘police and thugs’ with shaven heads, leather jackets and boots. The film was directed by Julien when he was a member of Sankofa Film and Video Collective. He was assisted by the film critic and curator Mark Nash.

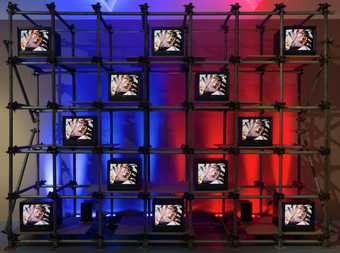

Looking for Langston exists in an edition of six plus two artist’s proofs. Tate’s copy is the first of the artist’s proofs. The work is projected on its own in a room measuring a minimum of five metres square and four metres in height, on a freestanding screen of at least four metres by three metres.

In this film Julien sought to create a piece of cinema which was inextricably connected to poetry and pictures. Through an examination of the private world of the Black artists and writers who were part of the Harlem Renaissance in the 1920s, the work explores desire – specifically Black, homosexual desire – and the reciprocity of the gaze. Though it revolves around the Harlem Renaissance, the film was made at the height of the AIDS crisis in the 1980s and has retained a feeling of urgency and relevance to this day, revealing the fact that the spectre of AIDS and discrimination continue to haunt the present Some actors in the film died after the film was made including Mathew Baidoo, Ben Ellison and Jon Iwenjiora. Julien has spoken of images from the film acting as reparational memorial sites.

Julien’s work breaks down barriers between different artforms, drawing from multiple artistic disciplines and tying together film, dance, photography, music, theatre, painting and sculpture in order to create the carefully produced images which are characteristic of his films. These typically combine fictional narratives with documentary and film-art techniques and Looking for Langston is exemplary of this weaving together of techniques and genres.

In exploring Hughes’s life and times, Julien employed a mixture of myth and reality, transitioning between different times and places, as he explained in his essay ‘Mirror’:

I wanted to make a work that would test its own chronologies, and I also wanted that work to have a timeless quality … Even the question of black and white, which served as a unifying aesthetic, was meant to help us move between time past and the present day. Living in the shadow of AIDS, one was seeing a lot of fear, a lot of denial, and a lot of gay man claiming to be bisexual – things that were also characteristic of the Harlem Renaissance. This gave us another reason to transgress between past and present.

(Isaac Julien with Cynthia Rose, ‘Mirror’, in Museum of Modern Art, New York 2013, revised and republished in Isaac Julien and Hilton Als, Looking for Langston, London 2017, p.11.)

As with many of Julien’s works, questions surrounding censorship and the expression and suppression of queer desire are articulated. Self-representation and the politics of cinematic and photographic images are also important themes. Indeed, when the film was released in America, it was met with public outcry as a result of Hughes being linked to re-enactments of Black queer sexuality. Essex Hemphill, in his essay of 1990, ‘Undressing Icons’, argued that the film’s reception was a case of the social suppression of frank discussions of sexuality and race; present not only in everyday society, but manifest too, within academic structures (Hemphill 1991, pp.181–3).

Further reading

Hilton Als, ‘Negro Faggotry’, in Black Film Review, vol. 5, no.3, Summer 1989, pp.18–19.

Essex Hemphill, ‘Undressing Icons’, in Essex Hemphill (ed.), Brother to Brother: New Writings by Black Gay Men, Boston, MA, 1991, pp.181–3.

Isaac Julien with Cynthia Rose, ‘Mirror’, in Isaac Julien: Riot, exhibition catalogue, Museum of Modern Art, New York 2013, revised and republished in Isaac Julien and Hilton Als, Looking for Langston, London 2017, pp.11–14.

Aïcha Mehrez

September 2018

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

You might like

-

Sir Steve McQueen Bear

1993 -

William Kentridge Felix in Exile

1994 -

Tracey Emin The Perfect Place to Grow

2001 -

John Smith The Girl Chewing Gum

1976 -

Dóra Maurer Timing

1973/1980 -

Dóra Maurer Relative Swingings

1973–5 -

Dóra Maurer Triolets

1981 -

Derek Jarman Blue

1993 -

Ben Rivers Slow Action

2010 -

Nashashibi/Skaer Why Are You Angry?

2017 -

Rosalind Nashashibi Vivian’s Garden

2017 -

Nil Yalter Harem

1980 -

Tina Keane In Our Hands, Greenham

1982–1984 -

Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industries (Young-Hae Chang, Marc Voge) THE ART OF SLEEP

2006 -

Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industries (Young-Hae Chang, Marc Voge) THE ART OF SILENCE

2006