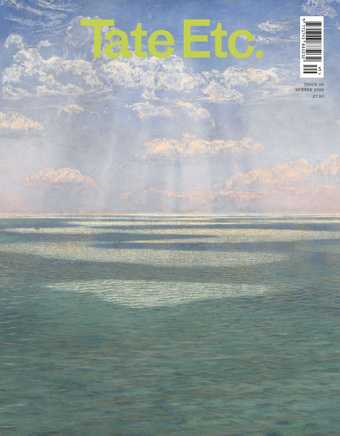

Joseph Mallord William Turner

Study of Sky

(c.1816–18)

Tate

I studied painting at art school in Australia in the late 1980s and early 1990s. The most prominent artist group at the time was the Melbourne-based ‘Roar’, but their wild expressionist canvases left me cold. My friends and I joked about starting a group called ‘Whimper’. Like everyone else, I was stone broke. I couldn’t afford to experiment too much, as oil paint – along with canvases and stretchers – was expensive. Watercolour – and its opaque cousin, gouache – wasn’t particularly popular at the time, perhaps because it was too quiet, too technically demanding, too seemingly old-fashioned. But I loved its modesty and the fact that it was cheap; it was a whispering kind of medium. It spoke to me and I heard it.

Of course, a great many artists have excelled in watercolour: in their hands, it gives the most monumental oil paintings a run for their money. J.M.W. Turner captured the vagaries of air and skies, rivers and oceans with the lightest of touches and the most observant of eyes. Gwen John’s tender, deceptively simple sketches – of herself, her plain Parisian rooms and the cats she shared them with – continue to break hearts with a few swift strokes. Joy Hester’s anguished faces and writhing bodies reflect, with the most economical of means, the rage she felt as her light dimmed. Paul Klee and Agnes Martin’s hypnotic, translucent grids – often constructed from nothing more than faint washes of colour and spindly, graphite lines – transform plain sheets of paper into magical portals. In Melbourne, my friend Peter Graham’s luminous image-poems make clear you don’t need a lot to create something miraculous: in the right hands, a scrap of paper, a pencil and a few tubes of watercolour will do.

Gwen John

Cat

(c.1904–8)

Tate

I remember the thrill of buying my first Winsor & Newton Watercolour Sketchers’ Pocket Box. It comprised 12 small cubes of paint, a tiny palette and a sable brush hardly bigger than a matchstick: a world of possibility in an object no larger than a hand. My first attempts, though, were dismal failures: the transparent colours blurred into mud and the paper buckled and flaked with too much water. I soon discovered that to labour over a watercolour is to ruin it: it’s a medium of brevity – it doesn’t let you faff about or change your mind. Unlike oil paint – which, being slow to dry, can be endlessly reworked, or a pencil mark, which can be rubbed out – watercolour cannot be corrected. I had been practising on flimsy notepads, which didn’t help: the thicker the paper, the better the paint behaves. I scraped my pennies together and invested in a pad from the holy grail of paper manufacturers, Fabriano – an Italian company that has been operating for around seven centuries – and felt as if I was communing with the artists of the Renaissance. But, however glorious the support, once you’ve made your mark, that’s it: the watery pigment soaks into the paper and, in the blink of an eye, it’s done. If you don’t like it, you have to start all over again.

The beauty of watercolour is that it’s portable; you can do it anywhere. You don’t need a studio or an easel or a spare week. Unlike so many other art materials, it doesn’t smell, or stain or poison you, and, despite the wondrous things so many artists have achieved with it, it’s not precious. It’s a medium that encourages daydreaming; if you let it, it will lead you to unexpected places. When all of a sudden it comes together, it’s like capturing sunlight.

If you are feeling inspired, you may be interested in some recent titles from Tate Publishing, including the Tate Watercolour Manual by Joyce Townsend and Tony Smibert, and How to Paint like Turner by Nicola Moorby, Ian Warrell, Mike Chaplin and Tony Smibert. A new edition of J.M.W. Turner: The ‘Wilson’ Sketchbook will be published in September.

Jennifer Higgie is Editor-at-Large of Frieze magazine. Her book on historic women’s self-portraits, The Mirror and the Palette, will be published by Weidenfeld & Nicolson in 2021.