Contents

- The Modern Lens: International Photography and the Tate Collection

- Alibis: Sigmar Polke 1963-2010

- Turner Prize 2014

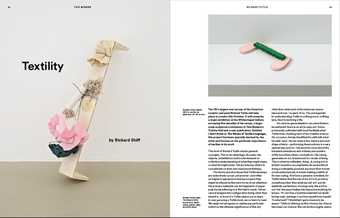

- I Don’t Know or The Weave of Textile Language.

- Conflict, Time, Photography

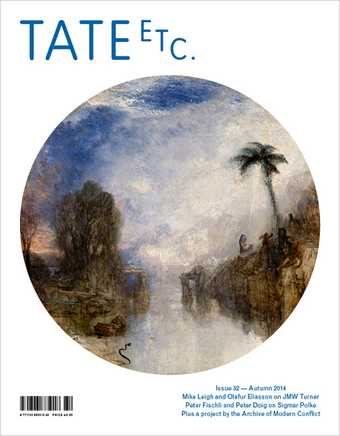

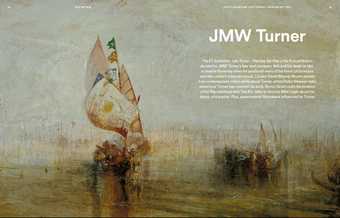

- The EY Exhibition: Late Turner - Painting Set Free

- In the studio: Phillip King

- Transmitting Andy Warhol

- Behind the Curtain: In the archive

Editor’s Note

‘The past is never dead. It’s not even past,’ said the writer William Faulkner. For the artists who bear witness to social change, political upheaval and possibly even war, they will inevitably be transformed by what they see and experience. The German artist Sigmar Polke (1941–2010) was born in Silesia – what was then East Germany and now present-day Poland – before, aged 12, he and his family moved west to Düsseldorf.

It is no surprise then that later, in 1963, Polke would organise the exhibition Capitalist Realist (along with Gerhard Richter and Konrad Lueg). Its title not only mocked the ‘socialist realism’ style, but also the consumer-driven art ‘doctrine’ of Western capitalism, and in doing so reflected the tensions that Polke had grown up with.

Several decades earlier in Europe, political instabilities would propel some artists to more tolerable creative environments, such as Judit Kárász (1912–1977), who left Hungary as it lurched politically to the right to find herself at the Bauhaus. Her photographs feature in The Modern Lens at Tate St Ives, alongside many other works by photographers from Eastern Europe, Latin America and Japan recently acquired by Tate.

As Faulkner’s line suggests, memory and remembrance is at the heart of how we relate to the past. Many of the photographers in Tate Modern’s exhibition Conflict, Time, Photography, which explores the relationships between photography and sites of conflict, did not witness actual events but have found ways to articulate them – from Chloe Dewe Mathews’s images of the various places where around 1,000 soldiers accused of desertion or cowardice during the First World War were shot at dawn, to Ursula Schulz-Dornburg’s pictures of landscapes ‘manipulated by conflict’.

The Second World War is still a live memory. The Japanese photographer Kikuji Kawada was a 12-year-old boy when the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima. He tackled its bitter legacy in his monochrome photo book The Map 1965. It features the stains and flaking ceilings of the Atomic Bomb Dome, the only surviving building at the heart of the detonation zone, mixed in with images of both discarded memorial photos and emblems of post-war Tokyo, such as Coca-Cola bottles and advertising images. Even though Kawada completed this project (an iteration of which will be in the exhibition) nearly 50 years ago, he knows that this past is forever moulding his present. As he writes: ‘As an observer, I would like to keep forcing myself into the future, never losing the sense of danger which emerges in the conflicts of daily life.’

Simon Grant