This research focuses on three of Tate’s collections: the art collection, the archive and the institutional records that document the history of the museum. It explores the tensions that arise between them, and how their boundaries can become blurred.

The articles in this section consider the role of the archive in art practice, as it has shifted from repository to medium. This transition is explored through three distinct strands: the challenges posed to Tate’s conventional structures and divisions by artworks that generate archive material; the process of establishing an archive for Tate Exchange and their Associates; and the museum’s decisions and criteria for material that moves between the archive and artwork collections.

Our work has been rooted in an emerging body of critical archival theory. This approach prioritises record creators – in this context, artists, participants and audiences – acknowledging that they should also be the priority record user and central to the processes of collecting and cataloguing. In the context of Tate’s collections and established archival practices, how and where Tate can make space for such practices?

The publications for this case study include Sarah Haylett’s essay ‘Living Archives at Tate: After An Archival Impulse’, which summarises the intentions and critical context of the research project. Taking her title from Hal Foster’s 2004 article ‘An Archival Impulse’, Haylett seeks to situate artworks that generate archival material within a wider history of archival artworks at Tate, while drawing parallels with archival theory and practice. She explores how Tate’s practices might expand to actively collect and engage with these artworks and the archives they generate.

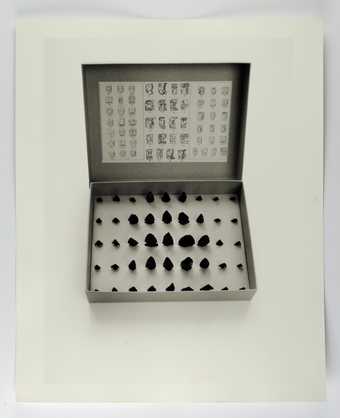

Susan Hiller

From the Freud Museum 1991–6

© Susan Hiller

Tate

In support of this essay, we have created a working proposal for the care and collection of artworks that generate archival material, and definitions for the three types of ‘archives’ at Tate. The research also informed our update of the Tate ‘Art Term’ entry for ‘Archive’. The final output of the project is a book chapter co-authored by the members of the Reshaping the Collectible team and Tate Exchange, which explores preliminary conservations about establishing an archive for Tate Exchange.1

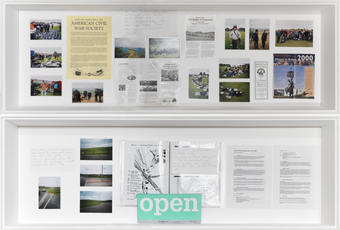

Jeremy Deller

The Battle of Orgreave Archive (An Injury to One is an Injury to All) 2001

© Jeremy Deller

Commissioned and produced by Artangel

Tate

Guerrilla Girls, Complaints Department operated by the Guerrilla Girls, Tate Exchange, 4–9 October 2016

Key texts for this case study

In addition to our ‘what we’re reading’ working document, some key texts for this archive case study have included:

Okwui Enwezor, Archive Fever: Uses of the Document in Contemporary Art, Göttingen 2008.

Ingrid Schaffner and Matthias Winzen (eds.), Deep Storage: Collecting, Storing and Archiving in Art, exhibition catalogue, Museum of Modern Art, New York 1998.

Stephanie Springgay, Anise Truman and Sara MacLean, ‘Socially Engaged Art, Experimental Pedagogies, and Anarchiving as Research-Creation’, Qualitative Inquiry, vol.26, issue 7, pp.897–907.

Antonina Lewis, ‘Omelettes in the Stack: Archival Fragility in the Aforeafter’, Archivaria, vol.86, Fall 2018, pp.44–67, https://archivaria.ca/index.php/archivaria/article/view/13643/15044.

Michelle Caswell and Marika Cifor, ‘From Human Rights to Feminist Ethics: Radical Empathy in the Archives’, Archivaria, vol.81, Spring 2016, pp.23–43.

Stuart Hall, ‘Constituting an archive’, Third Text, vol.15, issue 54 (Spring 2001), pp.89–92.

Simone Osthoff, Performing the Archive: The transformation of the archive in Contemporary art from repository of documents to art medium, New York 2009.

Kirsten Thorpe, Kimberly Christen, Lauren Brooker and Monica Galassi, ‘Designing archival information systems through partnerships with Indigenous communities: Developing the Mukurtu Hubs and Spokes Model in Australia’, Australasian Journal of Information Studies, vol.25 (2021), https://doi.org/10.3127/ajis.v25i0.2917.