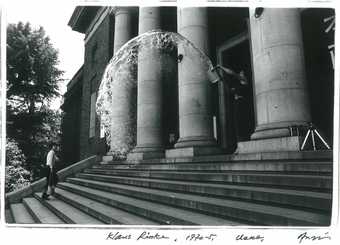

Shigeo Anzaï

Klaus Rinke, The 10th Tokyo Biennale ’70 – Between Man and Matter 1970

© Shigeo Anzaï

Lena Fritsch: What influenced your early photography?

Shigeo Anzaï: The reason I think it will be very difficult to get me to talk about photographs is that from the outset – and this is still the case now, especially since they’ve gone digital – I was never that interested in the photographs themselves. I am much more interested in the situation in which a photograph was taken. What I mean, and I think I have said this before, is that when I began my career I had a deep desire to paint, to produce fine art. I gradually switched over to fine art whilst holding down a regular job. In those days, the 1960s, the influence of American, British and foreign pop art was pretty strong, and that is what young people in Japan were interested in. That is when I found out about what we now call dadaism. I was really interested in dadaism, because as a movement it allowed people’s preconceptions to change. I produced a number of pieces inspired by dada; they were not installations back then, but paintings. I entered them into competitions and showed them in various exhibitions. I was really interested in this new movement from abroad.

Towards the end of the 1960s, Harald Szeemann held his big international exhibition When Attitudes Become Form in Bern in Switzerland. It was big news amongst my friends and I. That is when we started thinking that it was important to find a uniquely Japanese form of expression, independent of American pop art. That spirit still exists today: the idea of something uniquely Japanese. I did not know much about Arte Povera at that point. From the end of the 1960s, and into the early 1970s – including the Tokyo Biennale in 1970 – the move towards so-called experimental art, art that took place outside, in spaces other than art galleries, like public spaces, parks and university campuses, gained a lot of momentum. I got involved in that, and it was very exciting to be part of that situation with everyone.

But then an art event would be over. And when something is over it is very hard to explain to someone in words what happened and what people did. So, for example, if I was with Lee Ufan, he would ask if I had my camera, and if I did, he would ask me to take pictures, even if they were just snapshots.

Lena Fritsch: That must have been just before the 1970 Tokyo Biennale?

Shigeo Anzaï: Yes, maybe in 1969. At the beginning of 1970, a group of young people did a lot of experimental work, and exhibited it in a big public park. I also exhibited my work there, and took snapshots, which I still have. That was in January. And then in 1970, Japan held the Osaka Expo. When the organisers were inviting artists to be involved in the event, we were still completely unknown. The Gutai group was invited to be part of the Expo to create events and experimental work. I found out about that later.

So for me, 1970 was a year of going around with my camera with all these exciting people, taking part in new experimental work all over the place. But it was also a time when the whole of Japan was really interested in culture.

In May, Yusuke Nakahara said that he wanted to hire the Metropolitan Art Museum, in collaboration with the Mainichi Shimbun newspaper, to hold an exhibition. Nakahara based quite a lot of it on Szeemann’s exhibition list; I believe most of the artists were selected, apart from Joseph Beuys. Then there were Japanese artists who suited that form of expression: On Kawara, Yutaka Matsuzawa, Koji Enokura, Susumu Koshimizu, Katshuhiko Narita and people like that were brought in for the exhibition. But at that time the works on display were almost too crude to be called art. That is to say, no one was familiar with the format; Japanese people had no experience of that kind of work being referred to as art. As a result, people did not come to see it. For the newspaper, as an event it was a huge failure.

Lena Fritsch: That is interesting.

Shigeo Anzaï: There were people whose work took the form of an action, artists like Klaus Rinke, Hans Haacke and Daniel Buren, who were producing time-based work. Given that these were one-time-only works they could not be ‘displayed’. What fascinated me was that most of the interesting people who had been invited to participate, including Hans Haacke and Richard Serra, had informed the gallery in writing prior to the exhibition that they would not know what they wanted to do until they got to Tokyo. They said they would not get an idea of what kind of work they wanted to produce until they got on site. Instead, they would just send a message saying, ‘I’m coming to Tokyo on the nth of x month.’ Thinking about it now, that seems completely natural. The social situation surrounding the work and the situation of the gallery are all part of the process of deciding what to produce and where. Particularly with things like installations and happenings, an artist needs to know the social background so they can work out how to create a contrast, or how to express their own reaction to the situation. Such an approach overlaps with the concept expressed in When Attitude Becomes Form.

[…]

I used to work in an oil company laboratory. And it just so happened that opposite the laboratory there was another laboratory belonging to an American base, which carried out oil-related tests and things. I got to talk to the staff there at lunch times. That is where I learned to speak English. I did not learn it at school, just through everyday communication. Nakahara knew about that. He said, ‘You have got a camera, and can more or less speak English’. He said he could not pay much, but would I work for him part time? I knew that there were going to be a lot of people travelling to Tokyo for the Biennale, and I had the feeling that with these subjects something really interesting was bound to happen, so I agreed. I said that while I did not need much money, I wanted to know which artists were doing what and where they were doing it - as well as have the opportunity to be there with them. I can see now that the photos I took back then were actually really important photographs, because they are not photographs of the finished article. They are photographs of the preparations, or the hunting for materials.

Lena Fritsch: That’s what a lot of them are.

Shigeo Anzaï: Indeed. Even now, artists are very sensitive when it comes to choosing their site and how to reflect the character of that site in their work. You can see it in Kishio Suga’s work. A particular type of site will allow them to produce a particular piece with particular materials. The theme of the 1970 Tokyo Biennale was Between Man and Matter, and that is where I saw with my own eyes the kind of art that was being called ‘new’. It was a huge event for contemporary Japanese art. However, for the newspaper, the event was a huge failure.

Of course the Arte Povera artists came, and I met people like Mario Merz and Jannis Kounellis, Giuseppe Penone and Gilberto Zorio. I was able to understand and appreciate their way of looking and expressing things because of my awareness of the work of the young Japanese artists like Koshimizu, Narita and Jiro Takamatsu; and because I had been through a certain amount of training myself.. That made for very smooth communication. It was the same case with Carl Andre.

Lena Fritsch: That really comes across in the photos.

Shigeo Anzaï: Normally when you are there with a camera you might feel like you are in the way, or that you are being rude to the other person, but because that is where I started out, even now when I go to an international exhibition and journalists are not allowed in a certain area, the artists know me so they say ‘Oh, he’s alright!’ [laughs] It is a real advantage.

I think I have already talked about this, but I have been in touch with Daniel Buren ever since I shot his stripe art in the streets at the Tokyo Biennale in May 1970. I have known both him and Kishio Suga for more than 40 years. If you want to know why I am still going, it is because I still find it exciting. Maybe it is curiosity. It makes me really happy to see how an individual artist changes over time. It is easy for me to explain how an artist’s work has changed, and how a certain situation at a previous exhibition might have influenced their work in its current form. Some may call me a critic, but I am not a critic so much as an eyewitness. If I were to exaggerate somewhat, I would say that I have had fun writing my own personal history of global art.

Whilst there may have been a few magazines back then in the 1970s that wanted to use photos of the Japanese Mono-ha artists, there was much less interest than there is now. At the time I thought it was a waste of the archives, of all these original documents. In May of 1970 all these people were here – some from Europe, of course, like Reiner Ruthenbeck and Klaus Rinke…

Lena Fritsch: And Christo, for example.

Shigeo Anzaï: Yes, and Barry Flanagan and Roelof Louw, and the Arte Povera artists from Italy, and from America there was Hans Haacke, Carl Andre, Richard Serra, Sol LeWitt and Keith Sonnier. Three or four years later I wondered what all those people were up to, and it just so happened that in 1974 there was a Japanese exhibition at the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in Denmark. A lot of Japanese art went over. Some of the collection was rather traditional: from things like swords and armour through to works from the present day. I went to see it with Nobuo Sekine.

Shigeo Anzaï

Richard Serra, The 10th Tokyo Biennale ’70 – Between Man and Matter 1970

© Shigeo Anzaï

After the exhibition I crossed to Dover and went to London to visit Barry Flanagan. It just so happened that a Japanese critic had been over visiting Barry and he was leaving that day from Heathrow, so Barry suggested that we drop him off, then pick up my bags from the hotel on the way back and I stay with him, in the room the critic had been using. He let me stay with him for free for a bit. That is when I met all the young British artists like Michael Craig-Martin and Bruce McLean, the Nice Style group and Tim Head, as well as Gilbert and George. At the time I did not really understand the irony of British art.

Lena Fritsch: It is quite special, isn’t it?

Shigeo Anzaï: I think it is definitely different from the rest of Europe.

Lena Fritsch: That is interesting. I often think the same thing.

Shigeo Anzaï: The UK is not Europe. The UK has something that is uniquely British. I still think that the UK is not European.

All sorts of things happened to me after I went to the UK. I started working with Isamu Noguchi, as well as Anthony Caro, but before that I had made friends with a lot of Anthony Caro’s students. All thanks to Barry. Then there was a young man called Tony Stokes who had an experimental space called Garage. It did not have any money and soon went bust. But then various gallery owners donated money so that it could keep going. That is how experimental it was. That’s when I met Bruce McLean from Nice Style.

Lena Fritsch: It sounds like you really are interested in all kinds of art. I think that really comes across in your work. Even early on.

Shigeo Anzaï: When I speak to students, I tell them that when I see a piece of art for the first time, the work that is easiest to take on board is the old stuff. What I mean is…

Lena Fritsch: When you say ‘old’, how old do you mean?

Shigeo Anzaï: Traditional. However, work that is a continuation of academism is not that exciting. So what I try to describe is, to use a crude expression, the bizarre. I pay a lot of attention to things I find bizarre: the things that make you think ‘What is this?’ Things you cannot measure using conventional standards, where there is a 50/50 chance that what you are looking at is either crazy, or something completely new. That is what I tell them students should be thinking. Pay close attention: the things you think are weird are actually really important. You can call them strange, funny, or whatever you like. With British irony, for example, you have Gilbert and George’s Living Sculpture and Red Sculpture – which I photographed – or Singing Sculpture, and so on. When Barry asked me who I wanted to meet in London, I said I wanted to meet those sculptor guys who said they were a living sculpture. And Barry made the call for me. After he introduced me, I went to their office to photograph them. I had made an appointment and there they were in their suits waiting for me.

Lena Fritsch: I saw your exhibition at the White Rainbow Gallery recently and there was a photo there of Gilbert and George. Maybe it was from this meeting?

Shigeo Anzaï: They were a sculpture, yet they were alive; they sing, they dance. In a way, they fundamentally changed how people thought about sculpture… I photographed their Red Sculpture in Tokyo. I got more and more hooked on that kind of thing.

Lena Fritsch: What I find interesting is that those first photographs from the Biennale, as you said, were often of preparation and performance, but looking at photos like of the ones of the Gordon Matta-Clark project, it looks like you put a lot of thought into the best way to take them. They are really beautiful photographic compositions, not just documents.

Shigeo Anzaï: To put it simply, when you paint a picture you think about form and composition. When I make a print in the darkroom, I never do any cropping.

Lena Fritsch: You don’t? You think about all that when you’re taking the photograph?

Shigeo Anzaï: Right. That is part of the concept. But I was originally a chemist, so I do not find the darkroom as boring as some people.

Lena Fritsch: You enjoy it?

Shigeo Anzaï: I enjoy it. Printing photographs brings the same joy as painting a picture. The various things that I have done and the various experiences I have had come into play, in a good way.

The 9th Paris Youth Biennale took place the year after I came back from the UK. Quite a few people went from Japan, like Hitoshi Nomura, Naoyoshi Hikosaka and Etsutomu Kashihara. The Japan Foundation spent a lot of money on it, so they asked me to go over and take photos as proof of how that money was being used. But they did not have any money for me. They paid me for one month, and covered a one-way flight. That was as much as they had. I managed somehow and was there for almost three months. I took some interesting documentary photographs.

At that time Gordon Matta-Clark was doing really showy, event-type work involving architecture in the US. In Paris, he cut into old buildings with a chainsaw. I met him one day at an art gallery. He had a chainsaw with him. I asked him what he was doing and he said he was looking for a building to cut.

I said he would not be able to do it [laughs]. Then two or three days later I got a call at my hotel. He said that he had found a good location and that if he gave me the address would I bring my camera over? When I got there, I could hear the noise but I did not know where he was. There was a building being demolished next to where the Pompidou Centre was being built, and that was what he was cutting. I think this is the Pompidou Centre you can see behind here. As I was taking photos a Parisian lady came along and asked what I was doing in such a dirty place. I did my best to explain that it was an art event but she did not get it. Three years later in 1978 Matta-Clark died of cancer, but today he is popular again.

Lena Fritsch: It is interesting to learn how you think about composition: creating not just a document but an interesting photograph.

Shigeo Anzaï: The amount of information provided by a photograph depends on the framing. I instantaneously decide what information in front of the camera is the most important. Then I think really hard about what lens I should use and where I should stand in order to get the maximum amount of information into a single photograph. It is similar to painting a picture.

Lena Fritsch: You can really tell that from the photographs; it is reflected in them.

Shigeo Anzaï: For example, I took a photograph of the external wall of the building where Laurie Anderson’s loft was. This is where she lived. In the photograph, one can see these fake shadows that someone drew on the walls. Alongside these fake shadows, is my shadow, and her shadow. Laurie thought these shadows were funny.

Going back to what I was saying before, it is a waste of these documents not to, for example, show them to people in other countries. It took a while to organise my first trip to the US. I thought I should go to the US rather than the UK because I had been to Europe recently, so I went to the US Embassy in Japan. I spoke to them in my broken English and told them what I had been doing and that I wanted to know what American people of the same generation, who were interested in the same sorts of things, thought about these documents. The embassy typed out the details of the Fulbright scholarship for me, as well as the name of the director of the Rockefeller Foundation, and told me to apply. So I typed several letters to them, and at some point the Rockefeller Foundation said they were really interested – Fulbright responded straight away saying they had already used up their budget for the year so maybe next time.

Then, at some stage during our correspondence, I was informed that the director of the Rockefeller foundation came to Tokyo. The embassy told me he would be staying at a particular hotel from a particular date, and that I should make an appointment. So I filled a case with documents and went to the hotel. I had already more or less explained my interests and what I wanted to do, so this time I wanted to actually show him the photographs in my case. I called up from the lobby and said that I hoped he did not mind that I had arrived early, after which he told me to come up. So I went up and said hello, and then the first thing I asked was how much time he had set aside for me that day. He said it was a very practical question, and that I would fit right in in the States [laughs]. Because they start with the most important thing there, whereas Japanese people tend to beat around the bush. I hardly let him get a word in. I just went for it: I showed him my photographs, explained my work, and he said it was very interesting. Then he went home, had a meeting, and they decided to bring me over for a year.

To begin with I wanted to know what the American artists of the 1960s were up to at that moment. But they were all big names by then, like Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg. So I shifted my attention to the next generation and what they were up to. I met and photographed people like Bill Viola and Laurie Anderson, and performers like Meredith Monk. You know, the younger generation – like Keith Haring and Julian Schnabel.

After everything that has happened, the thing I am most grateful for is having been fortunate enough to meet all kinds of people, like I’m meeting you today. Who you meet, where you meet them, and when you meet them is really important, as well as making sure that the meeting leads to a next step. For example, sometimes I get a call from some American when they are in Tokyo, and they say ‘the artist Julian Schnabel said I should meet you if I came to Tokyo’. It is hard for artists to meet people who have a certain level of understanding of their situation.

Lena Fritsch: Of course. You need an introduction.

Shigeo Anzaï: If I had not known Barry Flanagan when I first went to London, I would not have known about Annely Juda or the Rowan Gallery. Now I know various people, like Anthony D’Offay, but I hardly knew anyone back then. The only way to find out was from the artists. I’ve been incredibly lucky in my encounters with people. Of course, maybe one’s personality plays a part, but it is not just that. You have to decide who you are going to meet, where and when.

Lena Fritsch: There is always an element of choice.

Shigeo Anzaï: I think I’ve been really lucky.

Lena Fritsch: What interests you most about the medium of photography? Is it that it is easy to document something?

Shigeo Anzaï: I have got a lot of experience now, so when I find myself in a situation I instinctively know how far away to position myself and where to stand. Some artists are very nervous and it is rude to stand too close. You might be disturbing them just to get a better picture, and you really must not do that, whatever happens. You just need to be sensitive to the antenna that tells you what the most important part of whatever is going on is. You cannot do it without that sensibility. It is not about the technical ability to take the photo; it is about understanding. It is a question of sensibility, and how you understand the subject. You need a lot of experience. You need to make a constant effort to be able to select, in your own way, from amongst the bizarre, the strange and the great. What I tell young students is to look at lots of things. Keep looking. Old things, new things, anything. Keep looking. You need to train your eyes, your heart and your feelings, or you will not understand in the moment. What makes me happiest is when I meet an artist after three years, and even though three years has passed we can just carry on as if nothing has changed and. I am lucky.

Lena Fritsch: That is very interesting: the importance of the human side to your photography.

Shigeo Anzaï: Ultimately, I think that at some level you need to make an effort to think about how you can make yourself a more attractive human being. When I was young, at high school I think, my grandfather told me that I was not suited to working for other people. He said I should make my own way, by myself. And that is how it turned out.

My family was really strict. I was born in the middle of World War II when the government was encouraging people to have lots of children. I was number seven of nine brothers. I call it lucky number seven, but my father calls it unlucky number seven. So I was brought up from a young age to think about how to become independent from my family. When I went the US, people asked me who had introduced me and I said that no one had introduced me, I had just typed a letter. Maybe that worked because it was America.

Lena Fritsch: Maybe.

Shigeo Anzaï: Nowadays, the Rockefeller Foundation is called the Rockefeller Foundation Asian Cultural Council, but it is mostly the same people who work there.

I was the one who introduced Takashi Murakami to the US. The Tomio Koyama Gallery told me that Murakami wanted to go to the US and asked me to write an introduction. I did not say anything good about him [laughs], but I did say that I would be really interested to see how time in the US would change his personality. And look what happened. [Laughs] Murakami-kun still says that if it were not for me, he would not be where he is today.

Of course we need to teach the academic perspective, but every person has their own limit, so they can also study for themselves if needed – there are plenty of art galleries for that. But unless you think about the personality you were born with, and how to live the life you were made for, I think you will find it hard to find work. That is the most important thing; that, and the fact that you have to really love your work.

Lena Fritsch: It is clear from your work that you love taking photographs, as well as meeting people and seeing their work.

Shigeo Anzaï: Yes. When I started taking photographs I often felt that my photos, in terms of sharpness and quality, lagged behind other people’s – that they were immature. But that did not bother Lee Ufan. He said that he preferred a blurry photo taken from the right angle to a sharper one taken from the wrong angle. That is what was important to him as an artist. You have to learn the difference.

Sometimes I get invited to photography schools. The students ask how they can get into this kind of work, and I say that I cannot answer that. Because even if I tell you what to do, and you do it, there is no guarantee that it will suit you.

Lena Fritsch: Thank you very much, Anzaï-san, for this interview and your precious time.

Dr Lena Fritsch is Assistant Curator, International Art, Tate