Sir William Rothenstein

The Doll’s House

(1899–1900)

Tate

How do you go about researching a work like this?

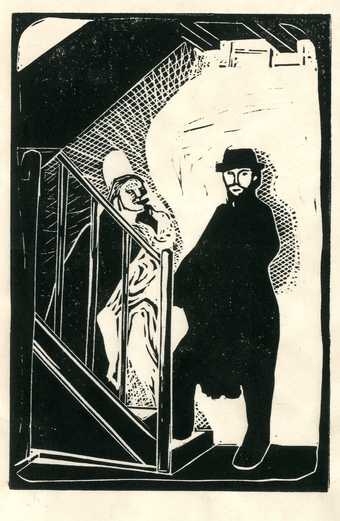

You start by looking at the painting – a lot. And that’s much harder than it sounds. You stare at it for thirty seconds and think, ‘I feel like I’m done’. But no one learns anything that way. You have to train yourself to really look. What I tend to do, and I did for this project, is to draw the work or make some version of it. That way I can spend almost as much time looking at it as the artist did working on it. I made a linocut of The Doll’s House in the early stages of research and that forced me to look at every inch and aspect of the painting, and think about it very carefully. The linocut wasn’t all that good in its own right, let alone accurate, but it was an important part of the process.

Then I moved onto primary material, and then more recent scholarship. We’re at a great moment today because there’s so much great material appearing online from contemporary newspapers – you can track down almost every review of the exhibition in which this painting appeared, and really immerse yourself in the contemporary context.

The project includes the first ever analysis of an early sketchbook owned by Tate. What did the sketchbook reveal about Rothenstein’s work?

I first saw the sketchbook, in passing, around five years ago. This project was a great chance to revisit it, having thought much more about Rothenstein’s career in the meantime. Aside from anything else, the sketchbook is a really good reminder of how precocious Rothenstein was. Later on in life, he was not seen as being wonderfully gifted, but at this stage in his career he attracted a lot of attention. He went to Paris when he was only seventeen, and was making these drawings which are reminiscent of Henri Toulouse-Lautrec, who he knew well.

It also shows that he was struggling to find a subject, as many young artists do. He was trying out many different things, some of which you never see again, such as the images of people playing in pool houses in Paris, which are unlike anything he ever does again. But there’s a great image of a woman standing by a fireplace, which is very like a painting he does more than ten years later. It’s wonderful to see those glimpses of what comes later, and of things he abandons.

The idea of carrying out in-depth research into such an enigmatic and mysterious painting is tantalising. Has it also been challenging?

It’s a really interesting question and there’s a kind of paradox at the centre of it. So many of the so-called great works of art in history are enigmatic – Velázquez’s Las Meninas or Van Eyck’s The Arnolfini Portrait – and you’re drawn to them because they’re enigmatic. At the same time, a part of you wants to be the one to unlock the work or to find a letter in which the artist reveals all. To some extent, you have to resist that urge, especially in a case like this when it seems the artist was probably setting the work up as a mystery, and playfully resisting analysis.

Samuel Shaw

Linocut (After The Doll’s House) 2015

In the section ‘Rembrandt and Reality’, you note that Rothenstein was an art collector, gallerist and art historian, as well as an artist. Was that typical of the time?

Rothenstein was part of a network of people in London at the time who were combining multiple roles. Good examples are Roger Fry, Charles Homes and D.S. MacColl, who combined roles including curator, artist, critic, lecturer and administrator. Their activity ranged across these boundaries – more porous then than now, I think – and it’s hard to understand their art without taking this into consideration.

For a brief period, when he painted The Doll’s House, Rothenstein was the artistic director of the Carfax Gallery in London, bridging the worlds of dealer and artist. He found it a struggle, however, to unite these two roles, and had to give up the Carfax job. This didn’t stop him taking on other roles, though, throughout his career. He was an abnormally energetic man.

What implications does your research have for how we view The Doll’s House today?

Hopefully, it will encourage more people to take a fresh look not just at The Doll’s House, but other paintings by Rothenstein also. I think lots of people knew The Doll’s House was a very interesting painting, but there has been a general sense that it’s his only interesting painting. By putting The Doll’s House in the context of other things he was doing around the same time, we can come to understand and appreciate them more. The project has made some works more visible than before, for example Porphyria, which is in a private collection and has barely ever been seen before.

Partly thanks to two recent exhibitions (From Bradford to Benares: The Art of Sir William Rothenstein, Bradford Museums and Galleries, 7 March – 12 July 2015 and Rothenstein’s Relevance: Sir William Rothenstein and his Circle, Ben Uri Gallery, 11 September 2015 – 17 January 2016) scholars are beginning to consider Rothenstein in many different contexts, and the In Focus project certainly adds to that.

What are your thoughts on the current display of The Doll’s House in the BP Walk through British Art at Tate Britain?

I’m really grateful for the questions that the recent rehang raised – particularly due to James Havard Thomas’s Lycidas which stands a few feet from The Doll’s House. I’d never thought much about that sculpture before, but I soon realised that the naming of it has these wonderful analogies with the naming of The Doll’s House – that it also has a title that appears to refer to a specific story but then when you map that onto the object, it all falls apart. Seeing the work from this different perspective really got me thinking.

What did you enjoy most about working on this In Focus project?

I always love the experience of looking at one thing for a long time. A lot of people think that art historians spend all of their time looking at works of art, but the reality is that, like everybody else, art historians spend a lot of time responding to emails, reading books and doing countless other things. Sometimes you don’t stop and just look at one painting for a long, long time.

Before I started the project, I was worried there wasn’t much more to say about it. By the end, I wanted to write four more sections. It’d be great to have had a section on staircases in art, for instance, or to explore the New Woman aspect of it in more detail. In fact, it’s reminded me that there’s so much more to say.