John Smith

The Girl Chewing Gum

(1976)

Tate

Why did you select this work by John Smith for the In Focus project?

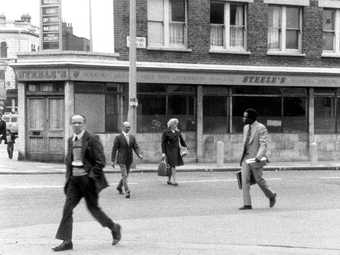

The Girl Chewing Gum is a work of central importance in the history of artists’ film, which is my field of specialisation. The film has long been a personal favourite of mine, but it also dovetails very nicely with my research interests, which include thinking through the place of the experimental film tradition in the art world and exploring the intersection of documentary and art, both of which are key issues raised by The Girl Chewing Gum. Although the film has been written about over the years, it has never received the kind of in-depth treatment that an In Focus project can provide. I saw this format as allowing an opportunity to explore the rich complexity of this film from multiple historical and theoretical perspectives. The Girl Chewing Gum is most often considered to be a humorous critique of the notion of objectivity in documentary filmmaking, which indeed it is. But there are also other very interesting ways of approaching it, whether as a film of place (rooted in Dalston, the filmmaker’s neighbourhood), as a way of exploring the changing status of film within art institutions, or as a key moment in the life and work of John Smith, who continues to be one of Britain’s preeminent artists today.

What did you discover about the film while carrying out your research?

I had seen the film many times before undertaking this project, but watching it closely and repeatedly in the course of my research led me to a whole new level of appreciation for the sophistication of its orchestration of voice and image. But I was also very keen to look beyond the film itself, to the context of its production and initial reception, and to its more recent incarnation as a gallery installation, as these were areas I felt had not been adequately addressed in existing scholarship. Through conversations with the artist and primary research at the British Artists’ Film and Video Study Collection at Central St Martins, I was able to provide an account of the film’s genesis and early life. In particular, the original programme notes – long out of circulation – were fascinating and revealing. I also became very interested in how John Smith revisited The Girl Chewing Gum in his 2011 exhibition unusual Red cardigan at PEER in Hoxton, London, in which the 1976 film figured as an absent centre around which the various elements of the exhibition congealed.

Smith’s film offers a reflection on the notion of truth in documentary filmmaking. How prevalent were such concerns at the time that the film was made?

One sometimes encounters the claim that documentary constituted a ‘bad object’ in artists’ film in the 1970s, to be refused because of its bogus claim to an authoritative, transparent representation of the world. This both is and is not entirely accurate. For some, this was certainly the case. However, to generalise this position as characteristic of the period as a whole would be to overlook the multifaceted engagements with documentary that occurred in artists’ and independent cinema in the UK at this time, including in The Girl Chewing Gum. Smith’s film takes up a nuanced relationship to documentary, engaging in a critique of its so-called ‘voice of God’, while in many ways remaining a documentary film. In the 1970s, often in response to the dominance of direct cinema in the 1960s, we see a flourishing of reflexive documentary practices of this kind, not just in the UK but around the world. Today this international tradition serves as a major inspiration for many contemporary artists who are working in this vein.

In the In Focus you trace the legacy of the film into the present day, as explored by the artist himself in the 2011 remake The Man Phoning Mum. How should contemporary viewers consider the film in relation to the remake and the new ways in which it is now exhibited?

The 2011 video remake asks us to look back at the 1976 film not just as an interrogation of voiceover conventions but as an historical record of place and pastness. In this way, The Man Phoning Mum proposes a (re-)reading of The Girl Chewing Gum as a documentary, when it has so often been understood as a critique of documentary. This seeming contradiction is in my view where a great deal of the film’s interest lies. But it is also important to recall that the 2011 remake was produced for the unusual Red cardigan exhibition at PEER, where it was exhibited alongside a number of other works that together explored the life of The Girl Chewing Gum beyond its initial moment of creation, outside of its original exhibition context (the cinema) and no longer tied to its original medium (film). This installation is both a part of and a reflection on how the infrastructures for the production, distribution and exhibition of artists’ moving image have been utterly transformed in recent years. The factors contributing to this shift are economic, technological and art historical. Examining the contemporary life of The Girl Chewing Gum provides a microcosm through which one can glimpse the workings of these larger processes.

What did you most enjoy about studying John Smith and this film at Tate?

This In Focus project gave me the opportunity to study a single work in great depth, which I had never done before but which I found very fulfilling. I very much like the way that the series combines the rigour of academic peer review with the benefits of public access online. It also gave me an opportunity to step slightly outside the format of a traditional scholarly article, both in terms of form and content. The online presentation meant I was able to integrate film clips into the piece, and it was terrific to be able to invite Patrick Wright to have a conversation with John Smith about The Girl Chewing Gum as a Dalston film. In a typical academic article, neither one of these things would have been possible, but I think they offer an enriched experience for both researcher and reader.