Introduction

Tate began its collection of performance artworks in 2005 with Roman Ondak’s Good Feelings in Good Times 2003, and now holds more than twenty-five performance artworks. The museum’s collection care division – specifically the time-based media conservation team and the collection management department – have been working to preserve these artworks’ continued existence as live events at Tate and beyond.

By exploring the current procedures for acquiring and caring for performance art at Tate, this essay will expand on the challenges these works pose to the museum, our current approaches to their management and conservation, and the possibilities that the continued acquisition of these works can present for collection care practices. In this sense, we are hoping to provide an overview of our processes that focuses on collection care practices and model workflows. Collecting processes can be, and commonly are, messy – timelines get expanded or contracted due to changes in access to materials and planned displays; communication with galleries, artists or estates can take its time; logistical challenges may arise; and financial contingencies can impact acquisition processing priorities. Tate’s acquisitions are increasingly incorporating more varied and diverse media that require extended collaboration between multiple conservation disciplines and specialisms. Tony Conrad’s Ten Years Alive on the Infinite Plain 1972, for instance, is primarily a performance artwork, but also includes film and sculptural elements that are fundamental to the concept of the work, and thus forms a valuable case study for this discussion.

This essay was written in the context of the research project Reshaping the Collectible: When Artworks Live in the Museum (2018–21), and focuses specifically on the institutional practices that underpin the acquisition of complex artworks such as Ten Years Alive on the Infinite Plain (hereafter Ten Years Alive).1 These practices were developed through years of experience across various collection care areas, and were influenced by the diverse set of artworks Tate currently has in its collection as well as by visiting researchers and practitioners, relevant scholarship, and research projects such as Reshaping the Collectible.

With this context in mind, this article will start with an overview of the acquisition process at Tate, exploring the processes involved in the acquisition of performance artworks with a particular focus on Conrad’s Ten Years Alive. We will explore the acquisition of Ten Years Alive in three phases as defined by pioneering projects like Matters in Media Art: the pre-acquisition phase, the acquisition processing phase and the post-accessioning phase.2 The pre-acquisition phase will reveal the points of contact between conservation and collection management activities – at least in Tate’s ecosystem – as well as what makes those two practices distinct during that first phase. The acquisition processing phase will pertain to conservation processes, focusing on documentation, film archiving, the care of sculptural elements in performance, and the care of performance beyond documentation. The post-accessioning phase looks at long-term management and conservation and will specifically address the ways in which artworks change after entering the collection. Although some of those processes are transferable to the acquisition of other forms of artistic practice, there are some that might not apply to other mediums.

This article is written from the point of view of collection care practice, specifically conservation and collection management. It was written collaboratively and its co-authors are members of these two teams at Tate.3 It is designed to be read both as an essay and as a usable resource, meaning that the sections can be read individually or as a set.

Overview of the acquisition process at Tate

The scope of Tate’s collection and collecting activities comprises British art from c.1500 to the present and international modern and contemporary art from c.1900 to the present. The acquisition process represents the beginning of the life of artworks as they enter the collection. The growth of Tate’s artwork collection is guided by strategy and priorities formulated by senior curatorial and collection care staff and approved by the museum’s Board of Trustees. All works of art proposed for acquisition go through an identical process that combines defined stages with established procedures to ensure that extensive due diligence is completed, as is appropriate to the activity of adding an artwork to the national collection. Within Tate’s Acquisition and Disposal Policy,4 the criteria that govern acquisitions require that ‘the needs of the Collection; the condition of the work and the costs of conserving and storing the work’ are considered with each acquisition.5

The process for considering acquisitions is as follows:

- Each acquisition proposal is initially discussed and assessed by teams of curators at dedicated meetings, known as Monitoring Groups.

- The recommendations of the Monitoring Groups go on to be considered by the Collections Group, which includes the Director of Tate, the Directors of Tate Modern and Tate Britain, the Directors of Collection (British and International Art) and Development, the acquisition and long loan team and the management accountant.6

- If the acquisition is approved within the Collections Group, it will then be considered by the Collection Committee, a sub-committee of the Board of Trustees composed of a selection of Trustees and senior members of Tate’s curatorial teams, which meets four times a year. The curator proposing the acquisition in question writes a Trustees note for Collection Committee meetings; this document outlines the background and characteristics of the artwork and how it aligns with Tate’s collection and collecting priorities.

- Acquisitions approved by the Collection Committee then progress to the final stage of the acquisition process, where they are considered by Tate’s Board of Trustees.

The collection care department’s approach to acquisitions is represented by three overlapping phases, starting when the artwork is considered as an acquisition candidate, moving through to the moment the work is accessioned and enters the collection, and extending beyond this time to the artwork’s life as part of the collection. In the case of collection care practices at Tate, the time-based media conservation team designates these phases as pre-acquisition, accessioning and post-acquisition.7 Pre-acquisition refers to the stage before the artwork’s acquisition is agreed; accessioning is the stage of processing the acquisition and lasts up until the artwork enters the collection; and post-acquisition refers to the conservation process that follows the artwork’s accessioning. These phases are also broadly observed within collection management practice, with the pre-acquisition stage relating to the process of bringing an acquisition candidate to a point where it can be accessioned and enters the collection. While for registrars the term ‘accessioning’ relates to a specific collection management process in which an artwork is formally incorporated into the collection, this statutory process can only be completed by the acquisition and long loan registrar team, with the support of the Head of Collection Management, Registration Manager and acquisition coordination team. Time-based media conservation uses this same term to refer to the process that is undertaken after the acquisition is agreed. In the context of this essay, therefore, we will consider the process of examination and conservation that is carried out after the ‘pre-acquisition’ phase as ‘acquisition processing’; similarly, we will consider the stage that occurs after the accessioning of the work by the collection management team as ‘post-accessioning’. We believe this will be an important step in promoting dialogue between the practices of collection management and conservation, both in this text and moving forward. This is because, as well as being situated within and emerging from the work of these two departments, this text also concerns a very specific practice within Tate – that of collecting.

The commencement of collection care’s pre-acquisition phase is most frequently instigated upon the request of the acquisition coordination team, following the acquisition’s consideration and agreement at a Collection Group meeting. The request often includes details regarding the artwork, alongside the details of who must be contacted to arrange receipt of the work. This information is sent to the applicable curatorial, collection management, conservation, development and intellectual property teams. The acceptance of the work at the Collection Group meeting indicates Tate’s serious intention to acquire the work and commits the institutional resources required for bringing this work onsite and assessing its condition.

Most commonly, the acquisition and long loan registrar team are the first collection care team to contact the source of an acquisition and engage directly with the artwork and its characteristics, which primarily relate to logistical matters such as packing, customs status, location, shipping and insurance. Conservation teams are initially contacted when specialist guidance is needed to ensure a work’s safe delivery to a Tate site. Due to the extent of Tate’s collecting programme, coupled with the complexities of arranging shipping, acquisition candidates arrive at a Tate site at different moments during the acquisition process, even if they were originally accepted for acquisition at the same time. However, artworks will only be formally acquired when the necessary conservation checks have been carried out and the transfer of title is complete. In the case of purchased works, such purchase is only completed upon the satisfactory receipt and condition-checking of all elements of the work.

Prior to Collection Committee meetings, conservation disciplines must give a preliminary assessment of the anticipated conservation costs that are associated with acquiring the work. This assessment allows the Committee to confidently consider the acquisition candidate with full knowledge of the costs that would be involved in acquiring the work, as well as costs associated with its display, long-term storage and care. This assessment takes the form of a report that is completed and circulated before the meeting takes place. The report – called the Pre-Acquisition Condition Report – paired with the Trustees note, serves as a basis for discussing and reviewing each individual acquisition. The acquisition must then be further endorsed and agreed by the Board of Trustees following each Collection Committee meeting.

The Pre-Acquisition Condition Report follows a template and is divided into two sections:

- Section 1: This consists of a standard template used across all conservation teams to capture key information about the work, including its condition, expected acquisition and display costs, and any risks to its present and future conservation.

- Section 2: This part is specific to each conservation team: paper and photographs, sculpture and installation art, paintings, frames and workshop, or time-based media. This section expands on the artwork condition, and details in greater depth previously identified risks and associated approaches and costs.8

This document is an essential step in understanding the artwork, what it means for it to be part of Tate’s collection, and its long-term preservation requirements. For time-based media acquisition candidates, the time-based media conservation team aims to identify all the elements of the artwork that we can expect to be supplied with, such as documentation and the highest quality copies available for audio-visual materials. These elements are negotiated with the source of the acquisition; this is most commonly done with, or in conjunction with, the artist, their gallery or their estate. In the case of time-based media artworks, having these conversations prior to receiving any materials allows the time-based media conservation team to understand the condition of the work and begin devising conservation treatments necessary to keep or make works displayable. This might include identifying a media-migration treatment or devising a documentation plan. We aim to gather this information at the pre-acquisition stage mostly because we deal with media that can be considered reproducible or can exist in multiple instances. The information gathered at this stage will then serve as the basis for the subsequent phases of the acquisition.

For time-based media acquisition candidates, the second phase – acquisition processing – often starts with the allocation of resources for the processing of the acquisition, so that priorities can be formulated. Processing includes arranging the delivery of the elements of the work that were agreed during the pre-acquisition phase (for example, the specific format for primary archival materials), as well as condition checking the artwork. Condition checking of a time-based media artwork involves checking each individual part that makes the whole and assessing if we have the most suitable primary archival materials and enough information to decide on how the work, as a whole, is to be shown. As time-based media artworks rely on different types of media and often also comprise sculptural and performance elements, the technical aspects of checking the individual materials of the work can vary immensely. Checking these materials can include quality control of audio-visual media (such as video, audio, slides or film), checking equipment and sculptural elements (that can either be unique or replaceable objects), or understanding the material conditions needed to perform a given gesture or movement. The inclusion of other media types within the materials of the artwork requires coordination with the relevant conservation team, as well as the acquisition and long loan registrar team. Interviews and questionnaires are often used during this stage to gather information on how the artwork is to be exhibited now and in the future.

The acquisition processing phase is finalised when the condition checks have been completed and we have all the information needed for the work’s future display. At this point, the time-based media conservator informs the registrars and other relevant conservation teams that the necessary checks have been made that allow the accessioning of the work to move forward from a time-based media conservation perspective. This triggers the acquisition coordination team to complete the acquisition of the work (when applicable), and to instruct the acquisition and long loan registrar team that they can accession the work into the collection. Acquisition processing, and the consequent act of accessioning, is then followed by a post-accessioning stage that stretches throughout the artwork’s life within the museum. At this stage, for artworks composed solely of time-based media, the time-based media conservation team finalises the archiving and documentation of all aspects of the work, which includes, among other things, data-logging into Tate’s collection management system, The Museum System (TMS), and the creation of production diagrams.9

These three phases are usually conducted following the same overarching processes for all time-based media artworks. All time-based media artworks enter through an identical acquisition process (as detailed above) and, therefore, all possess a Pre-Acquisition Condition Report. In recent years, we have seen how the diversification of Tate’s collecting practices has impacted various collection care procedures, increasing the layers of complexity that are associated with acquisitions. Performance art has been particularly generative in the ongoing development of our practices. The next section expands upon what makes performance so complex to acquire, and how we have adapted our practices to its idiosyncrasies.

Documentation of performance: Different perspectives in practice at Tate

Collecting performance art demands a balancing act between the sustainable documentation of artworks and the institution’s commitment to allow them to change. Similar to living organisms, performance artworks need certain material conditions in order to exist. Those conditions can vary enormously from artwork to artwork, and many performance works exhibit characteristics that require multiple disciplines – including conservation, collection management and curatorial – to document them to their individual specifications.

Documentation is a term and a practice that has become common in the vocabulary of collection care disciplines across all types of museum collection. This shared vocabulary, however, does not translate into a shared interpretation of the same term. The documentation practices for performance artworks that are carried out by collection management and conservation are complementary and interdependent.

In collection management, documentation is the sum of various mechanisms and techniques that record the particular characteristics and histories of an artwork. Tate’s collection management teams share in the statutory responsibilities that the institution must maintain in the documentation of the collection. This includes, but is not limited to, storage and movement, display, customs status and governance. We complete these documentary activities through various means, including both paper-based and electronic files, as well as the extensive use of TMS. From a collection management perspective, performance artworks present a challenge to existing practices, which commonly originated through the documentation of more conventional artistic forms such as painting, and must be adapted to accommodate the vagaries and the mutability of performative forms of practice.

For performance artworks, a simple mechanism of collection management documentation exists in which an exhibition format component is created within TMS to represent an individual activation (or planned series of activations) of the work at the display site. This component should only be used for this activation, being located in a particular place for a particular date (or date range), and should be deactivated at the close of the exhibition to indicate the conclusion of this instance of the performance. The history of this component, and therefore the display history of the artwork, although deactivated, will remain in TMS as a record of this activation and will be associated with both the object and the loan record. Such documentation helps to contribute to the historical record of the artist and their work, for instance in the compiling of a catalogue raisonné.

While the purpose of producing collection management documentation certainly resonates with the ways in which the term ‘documentation’ is used in conservation, the practice of producing conservation documentation is quite different. Like all conservation disciplines, the conservation of time-based media artworks has the goal of keeping artworks accessible (e.g. displayable) for present and future generations, and documentation is a key strategy in making that happen. For more traditional multimedia installations, documentation is produced to account for ways of assembling and displaying the artwork. In those cases, documentation is an individual strand of a larger strategy. For performance-based artworks, documentation is one of the primary conservation strategies to be applied, as there is an immediate expectation that the artwork will in effect be remade each time it is presented; it is not always the case that the artwork will have unique features that must be maintained from activation to activation. Documentation processes for the conservation of performance art at Tate were consolidated in our ‘Strategy for the Documentation and Conservation of Performance’.10 This strategy includes a glossary and four documentation tools: Material History, Performance Specification, Activation Report and Map of Interactions. The strategy currently works to identify approaches to the conservation of performance, its multiplicity, variances and nuances. The stated aim of the strategy is to ‘retain the “liveness” of a performance – the ability to activate it – and so it focuses on collecting information around the constant elements of what that performance is, or perhaps needs to be, in order to exist’. Moving away from the idea of capturing the ‘original’ or first performance, the strategy aims to ‘continuously capture the concept of the artwork, allowing the work to breathe and develop with each activation’.11 The iterability of conservation documentation, as well as its aims and scope, means it differs greatly from documentation produced in the context of collection management.

The range of possibilities for the documentation of performance artworks is intrinsically dependent on the characteristics of the artwork. Tino Sehgal’s This is propaganda 2002 is materialised in the gallery by an individual whom Sehgal refers to as an ‘interpreter’. We will now briefly describe this work from the perspective of a gallery visitor as they encounter it. When the visitor enters the space, a female gallery assistant turns and faces the wall and a voice is heard that begins to sing: ‘This is propaganda, you know you know, this is propaganda you know’. Only when the gallery assistant slowly turns to face the visitor on the last iteration of the words ‘this is propaganda’ does it become clear that she is singing and that it is live and not a recording. At the end of the refrain the details that would conventionally appear on the gallery’s written wall label are spoken, namely the title of the work and the name of the artist, along with the date of the work and when it was acquired. The visitor may ask a question, and a discussion may ensue, until someone else enters the gallery and the work begins again.

Motivated by a desire to resist his works being replaced by a photograph or a video, and wishing to step outside systems dependent on the circulation of objects and the production of material goods, Sehgal insists on the complete disavowal of material remains of his works. The conservation of This is propaganda therefore depends on memory and body to body transmission, a notion drawn from the field of dance. Sehgal does not allow the documentation of his work, ensuring that such materials do not come to stand in for the work. As such, the acquisition of This is propaganda in 2005 required us to depart from our standard processes not only with regard to collection management and conservation practice, but also in relation to the transfer of title, which was enacted through an oral rather than a written contract, in the presence of a notary with the involvement of a limited number of Tate staff. In that contract, Sehgal agreed that there could be a TMS record for This is propaganda, but all other information about the work must be committed to memory.

Other works, such as David Lamelas’s Time 1970 or Ondak’s Good Feelings in Good Times, are instruction-based and pose different challenges, and although they appear more straightforward in many respects, they exhibit alternative challenges that require adapted practices. Tate’s standard process when lending works to other institutions sees the loans out registrar team being the sole point of contact between Tate and the borrowing institution. This means that the complexity and precise specifications of the artwork must be conveyed accurately through the documentation that is sent to the borrower. The necessity for the borrowing institution to meet the requirements of the performance specification must be reinforced by the registrar; the registrar is also responsible for ensuring that the prescribed documentation, which is frequently much more extensive for performance and instruction-based works than it is for more conventional artworks, is gathered by the borrower and returned to the registrar. The importance of this documentation should not be underestimated as it is key to ensuring the integrity of the work in this particular activation, as well as maintaining the long-term care of the work in its most accurate and natural form.

These artworks can continue to thrive in the museum if the instructions that are at the core of what makes them what they are continue to be followed. However, the modes of their existence vary throughout time, developing during and between periods of storage and display. We consider that performance works, and installation artworks in general,12 are always partially present and partially absent in their institutional life. They are mostly dormant when living in storage, where they are catalogued and organised in different components, and where they may also take the form of documentation, film materials, sculptural objects, props and other analogue or digital objects. By contrast, they are considered active when they are installed and start to become visible, most critically through activation by performers.

For the museum, the understanding of the characteristics of an artwork, how they may change throughout its life, and what factors trigger change, begins with its acquisition. This moment also sets the primary requirements for displaying the work and the material conditions for the artwork’s activation. Although these requirements may only become fully evident the first time the artwork is displayed, the pre-acquisition stage of the acquisition process is when the materiality of the work is first negotiated, as will be seen below in the case of Tony Conrad’s Ten Years Alive.

Ten Years Alive on the Infinite Plain: Three Acquisition Phases

This section will focus on how we have approached the acquisition of Tony Conrad’s Ten Years Alive as it progressed through the acquisition phases of pre-acquisition, accessioning and post-acquisition.

Ten Years Alive is a complex performance and multimedia work that includes the live performance of a musical ensemble and a projectionist. The work was created by the filmmaker, musician, visual artist and teacher Tony Conrad in 1972, and was directed and performed by him multiple times until his death in 2016. The musical ensemble is complex, often comprising two violins, a bass guitar and a long string drone – an instrument developed and made by Conrad himself. The projections include a film made by Conrad featuring a vertical stripe pattern that, when projected on a loop, creates optical illusions that are made evident by the movement of the projectors throughout the performance.13

One aspect that makes the acquisition process of this work somewhat different to what usually happens at Tate pertains to the context in which the acquisition took place. The artwork was displayed at Tate Modern in 2017, shortly after it was proposed for acquisition. This meant that the time-based media conservation team were already acquainted with the work when the acquisition process started. Early on in the process, we realised that we would need to reach out to previous collaborators of Conrad to understand this complex artwork, as the parameters of the work – or what explicitly made the artwork what it was – appeared to us at that time to be quite fluid and uncertain.

Developing an understanding of the artwork as a whole, composite, artistic manifestation necessitated a collaborative effort across the institution – between different conservation specialisms, collection management and curators – in addition to those outside of Tate – including different expert networks, the artist and, later, his estate, as well as other external stakeholders. As part of the Reshaping the Collectible research project, the teams involved were able to design a fieldwork experiment that brought together all these stakeholders to discuss and activate Ten Years Alive at Tate Liverpool in 2019. This fieldwork was designed to test the documentation produced for the conservation of the work. Testing was particularly relevant as this complex performance work was acquired after the death of Conrad, who was the work’s creator and the main instigator of the previous thirteen activations of the artwork. While the fieldwork process is described elsewhere in this publication,14 this article will introduce some of the conditions of the 2019 Tate Liverpool activation and how it facilitated the acquisition of Ten Years Alive. In the next sections, we will also highlight some of the ways we adapted existing protocols to accommodate the inherent variability of the work, and how the strategies we are employing will impact the long-term conservation of this complex performance and film artwork.

Phase 1: Pre-acquisition

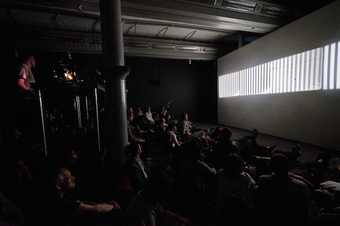

Fig.1

Performance of Tony Conrad, Fifty-Five Years Alive on the Infinite Plain, The Tanks, Tate Modern, London, 18 January 2017

Photo: Tate

In late 2016, Tate curators Andrea Lissoni and Carly Whitefield formally proposed Ten Years Alive as an acquisition to Tate’s collection. The artwork was, at the same time, on short-term loan to Tate, set to be displayed at an event which took place in the South Tank at Tate Modern in January 2017 (fig.1),15 nine months after Conrad’s death. This would be the first time the work – which has no formal score – would be performed without the direction and performance of Conrad himself, with his violin part being replaced by an audio track of him performing the piece. The long string drone instrument that Conrad designed was sent to Tate for the event, which also brought together the Conrad Estate, some of Conrad’s previous collaborators on the work, representatives from his gallery, and members of Tate’s curatorial and time-based media conservation teams. It is perhaps constructive to note here that other disciplines within the collection care department, such as its registrar teams, were not involved with this particular activation of the performance, in spite of the work’s approval for acquisition at the December 2016 Collection Committee and January 2017 Board of Trustees meetings. This can be ascribed to Tate’s organisational structure and the distinction between this activation as a temporary exhibition loan-in rather than the display of an acquisition candidate. As such, neither the displays team nor the acquisition and long loan registrar team had any involvement; the necessary registrarial responsibilities (those pertaining solely to the loan-in rather than any activity related to the acquisition) were instead completed by Tate Modern‘s exhibition registrar team. This instance can perhaps be recognised as a moment of activity ‘silo-ing’, as the involvement of the appropriate collection registrar team alongside the conservation team at this moment – even if only to share awareness – could have aided the effective completion of subsequent acquisition phases.

Due to the later involvement of the acquisition and long loan registrar team, this section of the essay will be divided into two, with the first part relating to the conservation process and the second relating to collection management.

1.1 Time-based media conservation

The time-based media conservation team’s involvement with the preparation and production of the Ten Years Alive event at Tate Modern in 2017 was particularly generative in assessing the material conditions needed to activate the work. To capture the material conditions of artwork in media such as performance or installation is only fully possible at activation. During the 2017 event we undertook initial discussions on the materiality of Ten Years Alive and the conditions for its transmission, conservation and documentation. Interviews with the performers provided us with important guidelines for activation.16 They also allowed us to gather relevant information on aspects such as the preferred film laboratory to use to create archival film materials, requirements for equipment and documentation, logistics, and a baseline to estimate the archiving and display costs for the artwork. At this time, we were not sure if Tate was going to acquire Conrad’s long string drone alongside the artwork, but it was clear to us that the instrument was something we needed to be able to remake as necessary due to its active use during the performance of the work. The activation at Tate Modern also provided an ideal opportunity to document the performance of the work, with time-based media conservation and Tate Media producing video and audio recordings of the rehearsals and performance (fig.2).17

Fig.2

Musicians Rhys Chatman (left), Angharad Davies (centre) and Dominic Lash (right) rehearsing for the performance of Fifty-Five Years Alive on the Infinite Plain at The Tanks, Tate Modern, January 2017

Photo: Tate

Fig.3

Projectionist Andrew Lampert preparing a film loop for the performance of Fifty-Five Years Alive on the Infinite Plain at The Tanks, Tate Modern, January 2017

Photo: Tate

This event introduced us to key actors who, in one way or another, had been involved in prior performances of Ten Years Alive, and who were therefore immediately considered to have an important part to play in devising a long-term conservation strategy for the artwork. For instance, the artist, archivist and curator Andrew Lampert, who had restored Conrad’s work for Anthology Film Archives, performed the role of projectionist at the Tate Modern event (fig.3). Working with Conrad’s previous collaborators, we started to understand the key elements of the work, such as the roles of the musicians and projectionist, and how they related to one another within the performance. Interviewing previous collaborators allowed us to consolidate our belief that the artwork was dependent on distinct ways of playing and interacting that were not easily communicable. The performers often reflected on how important it was to play alongside Conrad, due to the moments of learning that occurred through their interaction, but also because parts of the piece involved some form of engagement between the musicians. Besides having to deal with a whole new artwork set-up without Conrad, the experienced performers then also had to come to terms with a new element of the performance: the audio track that replaced the artist’s violin in the piece. This sound element, although effectively absent from previous performances, seemed to be turning into a new constant feature of the artwork. In addition, some aspects of Conrad’s personality made us think about how we might ensure the growth or variation of the artwork in the collection. This was something that could happen by framing a set of elements as being constant and by fixing those framings in subsequent activations.

After realising how fluid, and somewhat organic, Conrad’s approach to his overall practice was, we came to see that we had to interrogate these categories and framings further in later stages of the acquisition process. Once we had understood which of the artwork’s elements are constant and which in flux, and how this impacts the requirements to activate the work, we sought to list out the many aspects that we had to take into account when undergoing its activation. The 2017 activation helped improve our knowledge around the technical and logistical aspects of the work, such as the minimum equipment requirements (projector type, PA system, video and audio capturing equipment). Yet some questions remained:

- In which ways could the artwork adapt to different spaces? What would be the guidelines and requirements of the gallery space?

- What made a performance of Ten Years Alive a performance of the artwork? What core aspects form its identity?

- How could the work be performed and by whom? The absence of an authorised score, the recent addition of an audio track, and the lack of clear directions given by Conrad to the three performers that played the piece in 2017, made this question all the more relevant.

- What were the defining moments in the performance? For example, how was the beginning and end of the performance signalled for the audience and between the performers?

- If we were to decide to remake the long string drone, what was the process for this? Would we be able to capture information on how to remake the instrument?

- What was the role of the technical staff? What information would assist them?

For the time-based media conservation team, the pre-acquisition phase of Ten Years Alive ended with the activation of the performance in the South Tank in 2017, which almost coincided with the moment that the Pre-Acquisition Condition Report was written and circulated to key stakeholders. The first requirements and guidelines gathered at that stage laid the groundwork to develop the acquisition process further and prepare the artwork to be accessioned at a later stage.

1.2 Collection management

For collection management, the pre-acquisition phase ordinarily begins with the formal notice of the intention to acquire an artwork being issued by the acquisition coordination team, and in the case of Ten Years Alive this notice was received in 2016. When coordinating the receipt of a complex artwork like Ten Years Alive – one that is composed of multiple elements and media types – an initial collection management process is carried out that involves determining exactly what material will be received as part of the acquisition and the status of such material. Establishing the status of the different elements influences how they are viewed and managed, affecting such logistical considerations as the appropriate manner of shipment, customs status and financial value (for insurance purposes). The components that we received as part of the acquisition of Ten Years Alive included film materials, written documentation, audio-visual archival materials and a version of the long string instrument. In liaising with the time-based media conservation team it was ascertained that the film materials, written documentation and audio-visual archival materials were reproducible media, and therefore that the time-based media conservation team could themselves arrange the receipt of these materials. As a matter of practice, the acquisition and long loan registrar team are the only party permitted to arrange receipt of acquisitions; the only exception to this is in the case of certain time-based media acquisitions wherein the material to be shipped is determined to be non-unique and reproducible, as with Ten Years Alive. On these occasions, the time-based media conservation team can arrange receipt of the material, but the registrar team must still formally receive the material upon its arrival at the appropriate Tate site.

During this phase it became evident that the status of the long string instrument was unclear. Although the provenance of the version of the instrument that Tate was to receive as part of the acquisition was already known – it had recently been fabricated by the artist’s estate – neither the longevity of the instrument nor the absolute rights to refabricate it in the future were confirmed. Coinciding with this, the status of the instrument was somewhat ambiguous as it could equally be regarded as a sculptural element, an activated object or (simply) a musical instrument.18 It was therefore agreed that the shipment of the instrument should be coordinated by the acquisition and long loan registrar team. Liaising closely with the artist’s gallery, this team arranged shipment to Tate. In spite of the long string drone’s ambiguity, it was deemed appropriate for this brand new version, constructed by the artist’s estate rather than the artist himself, to be shipped from New York via tracked courier service rather than via costlier museum-specification transport. The insurance value when shipping the work was fixed at the estimated refabrication costs (consisting of both material and labour costs) and it was imported at such value, and was designated as a musical instrument rather than an artwork. The delivery of the instrument was received by the registrar team and it was documented on TMS among the first components listed as part of the artwork.

Phase 2: Acquisition processing

During the acquisition processing phase of an artwork, we undertake in-depth research, including into the work’s previous activations, and write what we have come to call its ‘material history’. The material history of artworks aims to map the socio-material conditions that led to each activation of the work. This can mean, for example, identifying who participated in the execution of the work and what their roles were, characterising the materials, sculptural elements and equipment that were used in each instantiation, and mapping the decision-making moments that influenced how and when the artwork varied. Understanding the artwork through its materiality also means interrogating the contexts in which it has been shown and how those contexts may have impacted the artwork’s identity.19 We use this material history alongside instructions supplied by artists, galleries or estates, and our own documentation tools.

The acquisition processing phase for Ten Years Alive started in earnest in 2018 when the time-based media conservation team and acquisition and long loan registrar team resumed contact with the Conrad Estate and Greene Naftali gallery to discuss the delivery of elements of the artwork and related documentation. Various elements of the work were condition checked by the relevant conservation teams. The time-based media conservation team produced and condition checked archival film materials, digital video and audio, and performance documentation, while also checking the condition of the long string instrument provided by the estate in collaboration with members of the sculpture and installation art conservation team. From a conservation perspective, the main question raised by the Reshaping the Collectible research project and the time-based media conservation team members involved was whether the documentation generated would be enough to ensure the viability of future activations of Ten Years Alive. In order to answer this question, we had to be able to produce the documentation and then evaluate its capacity for transmitting the performance. The time-based media conservation team and Reshaping the Collectible project team devised an experiment that produced a new documentation model, creating what we called a ‘dossier for transmission’, and tested whether the model would work in transmitting the performance to new generations of performers by activating the artwork using nothing but the documentation provided and produced by Tate.20 At the core of conservation’s approach was an awareness of how dependent the artwork was on the people who had performed it, or otherwise contributed to its materialisation in any way – a group of people that the time-based media conservation and the Reshaping the Collectible project teams came to call the ‘social network’ of Ten Years Alive.21

The first phase of this experiment consisted of the development of the dossier, for which we drew in the network of people who were involved in the previous activations of Ten Years Alive. The structure and content of the dossier were discussed in an interdisciplinary way, propelled by the project team, who brought together interested stakeholders. The dossier took on the format of current documents used at Tate (namely the Performance Specification), so that the process of testing the dossier could also be useful in understanding the possibilities and limitations of our current documentation methods.22 Besides providing us with the opportunity to discuss and evaluate our documentation, the testing also allowed us to access information that was essential in devising our procedures for the conservation of the artwork and ensuring Tate’s acquisition of the work. The conservation teams consider an artwork like this to be ready for accessioning once we have fulfilled the following requirements:

- Analysed all data collected from interviews and audio-visual materials, including undertaking follow-up interviews.

- Analysed documentation delivered by the artist’s estate.

- Created and condition checked archival film materials and film prints to be used in future activations.

- Created a performance specification reflecting data collected and experiences of activating the artwork.

- Created ‘teaching documentation’ for transmission: ‘guidelines for projectionist’, ‘guidelines for musicians’ and ‘guidelines for sound engineer’.

- Curated, organised and carried out quality control checks on all audio-visual documentation in preparation for ingestion into the digital repository.

The following subsections will detail some of our procedures during the acquisition processing phase – specifically the ones related to conservation – and how they were adapted to accommodate the many objects, digital and otherwise, and practices that are part of Ten Years Alive. These subsections are: (1) documenting the whole artwork, (2) the film elements, (3) the sculptural component and (4) the performance beyond the documentation.

2.1 Documenting the whole artwork

One of the most important practices to carry out when documenting artworks that rely on performative practices is the development of a documentation structure. This structure aims to guarantee the access and preservation of various files that form part of the documentation, without losing sight of the artwork as a composite, and yet whole, entity.

Different types of documentation can be associated with an artwork. Normally, we work with two types of documentation:

- Working documents, such as an object’s condition report or a performance specification. These are useful to capture and archive how an artwork varies or evolves with time or in different contexts.

- Archived documents, such as video recordings of an activation or instructional videos. These usually comprise documentation that is not meant to change and can serve as a reference point for specific activation contexts. Sometimes these archived documents include artist-approved media that hold key content on how to activate a performance.

The different statuses of these two types of document provides them with different levels of access and different storage locations.23

> Conservation records and the ‘artwork folder’

The working documents that Tate conservation teams produce are gathered together during an artwork’s institutional life and are stored in what we call the ‘artwork folder’.24 An artwork folder is created within the conservation record for each artwork in Tate’s collection and it has a total of nine sub-folders, each having a specific scope (see fig.4). The curation of the various digital files in the artwork folder is an ongoing and essential step in acquisition processing. While ensuring the overall coherence of file locations across our workflows, we also save working documents in our shared drive to guarantee their long-term accessibility.

| Sub-folder | Type of information stored |

| 1 Introduction | Written summary of key actions, changes and updates relating to the artwork, for instance noting the performances of Ten Years Alive at Tate Modern in 2017 and Tate Liverpool in 2019. |

| 2 Specificaitons for Display | Performance and display specifications. In the case of Ten Years Alive, this also includes a manual developed by filmmaker and projectionist Andrew Lampert in 2019, guidelines for the projectionist and musicians, and a list of previous performers. |

| 3 Structure and Examination | Condition reports and information about different features of an artwork, such as the equipment, media and sculptural components related to a performance. |

| 4 Display History | Individual folders that each hold records relating to a specific activation. |

| 5 Acquisition and Registration | Email communication with galleries and other stakeholders, in and out receipts relating to the movement of components, invoices, budgets, Trustees notes and the Pre-Acquisition Condition Report. |

| 6 Conservation, Strategy, Research, Treatment, Ongoing | Material history of the artwork, conservation treatment reports. |

| 7 Artist Participation | Interview files, scripts and transcripts. |

| 8 Art Historical, Research and Context | Art historical information, reviews, newspaper articles, relevant research links. For Ten Years Alive, this folder contains links to research carried out as part of the Reshaping the Collectible project. |

| 9 Images | Images indexed by year and event, for instance images of Ten Years Alive being rehearsed and performed at Tate Modern in 2017 and Tate Liverpool in 2019. |

Fig.4

Table showing the current structure of the artwork folder, with details of the type of information stored in each sub-folder and examples specific to Ten Years Alive

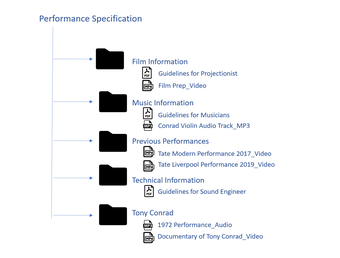

In the case of Ten Years Alive, the documentation of the artwork was collated as part of a ‘dossier for transmission’, as outlined above. The dossier comprises working documents such as guidelines for musicians, the projectionist and the sound engineer, and archived documents such as audio-visual media of specific activations (see fig.5).25

Fig.5

The current structure of the dossier for transmission, created in October 2019

Image: Louise Lawson and Ana Ribeiro, April 2020

The working documents in the dossier were distributed to the relevant sub-folders in the artwork folder, with the structure of the dossier itself already developed to work within existing documentation structures.26 This process has allowed the absorption of the dossier into our current practice, which means that any member of staff will be able to update the relevant documentation and collate the dossier each time the artwork is scheduled to be activated. In our understanding of the term, the dossier can therefore be defined as a group of carefully curated documents that are set up in a precisely formulated structure that will evolve over time. This approach ensures that previous versions of documents are retained while also allowing for revision and change – an example being the Performance Specification situated in sub-folder 2, ‘Specifications for Display’. Saving the previous versions of our working documents is essential in fostering our institutional memory regarding how the artwork changes over time. Additionally, it gives us the opportunity to reflect on our practices and engage more actively in the ongoing revision of our procedures.

> Audio-visual documentation

When acquiring a performance-based artwork we may receive audio-visual media which, at the point of processing the acquisition, consists primarily of video and audio of past performances or instructional videos. We can also capture additional audio-visual media, for example when an artwork is activated during the acquisition processing phase, which was the case for Ten Years Alive. During this phase we realised how important the role of documentation had been for Conrad: interviews with his past collaborators made clear the importance the artist placed on documenting each activation of the work. In fact, the audio was most often recorded by Conrad himself during performances.

For the 2017 and 2019 activations of Ten Years Alive both audio and video recordings were produced alongside the use of photography. To ensure successful audio-visual documentation we devised a strategy to determine the resources needed, the type of capture and a schedule of what we wished to record and how.27 We wanted to ensure that we would gather comprehensive information from both the rehearsals and the performances that would inform our understanding of the artwork. While rehearsals reveal processes of decision-making that can inform, among other things, our performance specification, capturing performances allows us to have direct reference material for each instantiation of the work, including information on the musicians, the film projections and the audience, such as how they enter and leave the space. We thought carefully about the placement and position of the camera and audio recording devices. The camera was static so as not to disturb the performers and the film projections. The camera also needed to capture the striped and flickering nature of the film. The audio recorder was placed in a position that allowed for calibration according to the conditions of the space. In the process of capturing this documentation, it was also important to check media formats for both video and audio recordings to ensure that they would render files with relative quality, high resolution and stability (for instance, we therefore used .WAV rather than .mp3 formats for the audio).

These media files are cared for like any other audio-visual element of a time-based media artwork. When acquiring audio-visual media, we look to understand how they were produced and negotiate the delivery of the ‘best quality’ primary formats that are available for archival purposes.28 The supplied audio-visual documentation or media is then prepared to be archived into Tate’s digital repository; this process follows specific quality control protocols developed for digital files. This includes condition checking the media by carrying out quality control analyses for playback consistency and future accessibility.29 If any problems are found on the files, the time-based media conservation team works together with galleries and artists to resolve them before completing the archiving process. Once the condition checks are finished, the media files are organised as artwork ‘components’ and their metadata is documented on TMS.30 The documentation of digital components into TMS is usually undertaken by time-based media conservation.

Artwork ‘components’ can be any individual element of the work, such as a digital file, a film print, a folder with photographic files or a sculptural element. The components created for Ten Years Alive, for example, included individual audio-visual documentation files, the film material for archiving, and the long string instrument. Artwork components are meant to exist in perpetuity, except for what is termed ‘exhibition formats’: media that is created for a specific exhibition and that can be deactivated after the event if not relevant to the media history of the artwork (an example of this would be an exact copy of an already existing exhibition file). When creating ‘components’ we follow a labelling protocol developed by the time-based media conservation team for use within TMS.31 Time-based media labels – which form part of the labelling protocol – were also introduced to help us track parent-sibling relationships between different components of an artwork, such as primary archival materials, production materials and exhibition copies. This method is particularly relevant when it comes to audio-visual files given their reproducible nature; files may be migrated or produced afresh to be shown with new technology or in new contexts.

Originally developed for film, slide, audio and video-based artworks, a component’s label allows us to map (1) the year a component was created, (2) how many channels make up the artwork (for instance, how many individual projections or images), and which channel is expressed by that specific component, and (3) which material it was created from, i.e. what is its parent component.32 Through this label we can therefore access the parent and sibling relationships between components of the same artwork, allowing us to track the most recent copies of a file and to go back to previous generations if necessary.

The documentation of audio-visual media in our collection management system is then complemented by our media archiving processes, which follow a workflow tailored to the characteristics of our infrastructure. It is important to ensure that media files follow our standard media archiving processes to ensure that all such materials remain accessible for future activations of an artwork.

2.2 The film elements

When it comes to film preservation, Tate normally requires the delivery and production of preservation and duplication material for the film and sound components during the acquisition process. To allow for the ongoing preservation of film within Tate’s collection, it is standard practice to ensure we hold preservation material that can be used to reproduce film for its exhibition and display. The nature of these materials is dependent on the production and techniques employed in the making of the original film that is being acquired. To ensure that we can support the continued display of works with film materials, we require that primary archival materials are provided at acquisition. We consider these to be the materials that are closest to the original output of the artwork. They are usually provided by the artist or by the gallery and, as with audio-visual documentation, they are expected to be the highest quality materials we can access. Normally these are the artist’s negatives or the digital intermediate files necessary to create the physical film prints. From these we then produce primary archival materials, which are high resolution copies that allow us to create exhibition prints. Those primary archival materials are then stored and cared for according to current best practice.

In the case of Ten Years Alive, the gallery provided us with a copy of the film element that had been used by Conrad in the past. To avoid generational loss – a loss of data that happens when analogue files or images are copied – we required access to Conrad’s original, silent, black and white 16 mm reversal print.33 We then worked with Colorlab, a film laboratory in Rockville, Maryland, and with Andrew Lampert and Greene Naftali gallery to create copies of the film, which included negatives and digital prints that would allow us to produce additional film reels in the future. Based on Ten Years Alive’s film production history and the primary archival materials, we requested the following items:

- Two duplicate negatives, directly looped from the original reversal print, one for preservation and the other for duplication. Duplicate negatives are the primary archival materials that will allow us to print additional performance prints in the future.

- Two check prints made from each duplicate negative, which are production control prints and will not be used for performance purposes. These prints allow us to see what results from printing directly from the duplicate negatives, as well as allowing us to control the production of Tate’s materials against the Conrad Estate’s original film materials, but also to control the process of making new release prints out of duplicate negatives in the future.

- Four release prints which will be used during activations of the performance.

- One fine-grain positive, which is a black and white intermediate positive image generated from a duplicate negative. This positive, therefore, allows us to create additional duplicate negatives in the future.

- Digitisation of the original reversal print. Even if Tate has no intention of showing 16 mm film works digitally in the near future, we preventatively requested the digitisation of primary archival materials.34

In addition to the above, the estate provided similar materials such as duplicate negatives, check prints and release prints to serve as verified proofs – copies that have been verified or approved by the artist, the gallery or the estate.

Film elements, like any other media holdings, go through condition checks, quality control assessments and documentation procedures. The documentation of film artworks is then complemented by the production of working documents that specify the requirements for displaying the artwork. When determining the material conditions needed to project film artworks, we use calculations and try out various set-ups in virtual settings, using platforms such as Google SketchUp. Where an installation is particularly complex, we occasionally develop mock-up installations in a dedicated space at Tate Store, the museum’s collection centre. As will be shown below, this was the case with Ten Years Alive. Testing was critical to ensure we had tried out and confirmed the projector set up, layout and positioning in the gallery space, so that we could confirm our understanding of these aspects of the work and ensure that our documentation would be accurate.

> Testing the film projections and equipment

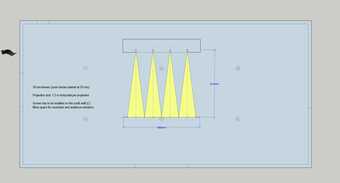

In March 2019 the time-based media conservation team organised a session aiming to test the projection elements for Ten Years Alive.35 The trial aimed to explore how the projectors needed to be set up, testing the layout and positioning of the proposed gallery space to be used for the activation of the piece, which was the Wolfson Gallery at Tate Liverpool. It was also used as a moment to invite the curators leading on the acquisition, Andrea Lissoni and Carly Whitefield, and the curator and projectionist Mark Webber to be part of the test and discuss the layout of the projectors.36

Fig.6

Drawing showing the Wolfson Gallery’s spatial dimensions and one of the proposed arrangements for the four film projections

In preparation for the test, an initial sketch was drawn to explore different options for the layout (fig.6). Four 16 mm film projectors from the time-based media equipment pool were identified for use, alongside a range of projector lenses. The aim of the testing was to better understand the way the projections behave and to identify all of the equipment that we would need for the Tate Liverpool activation.

At this point, the documentation suggested that the central two projectors should be positioned straight, while the outer two projectors should point across one another, projecting onto the opposite outer sides of the projection area. When the projectors were set up this way in the mock Wolfson Gallery (which included accurate room dimensions and fixtures), their positions created observable keystoning in the projected images – an optical effect wherein the image becomes distorted. An alternative arrangement was tried out in which the two right and two left projections were crossed, and this produced a better horizontal alignment of the projections in the prepared setting.37 This experience showed us how different set-up solutions for the film projections in specific spaces can potentially solve issues such as keystoning. We also realised that the columns in the Wolfson Gallery would interrupt the projected image, such that the narrower wall in the gallery space would need to be used for the projection area (fig.7). To achieve this, 25 mm lenses were selected to accommodate the largest amount of distance possible from the projector to the wall, allowing for maximum public seating without the gallery columns blocking the projections.

Fig.7

Drawing made after testing showing the Wolfson Gallery’s spatial dimensions and the position of the screen (left) and the projector platform between the four columns (right)

The testing also revealed some interesting nuances. For instance, the team discovered that the optimal film loop length was approximately 82.5 inches (210 centimetres), and that adjusting the back arm of the projector so that it was nearly vertical – rather than the usual approximately 45 degrees – allowed the film loops to run more smoothly, improving the overall running of the film.38

The movement of the projectors was also tested to better understand their choreography, as we knew that this needed to be both smooth and seamless. Methods used in previous activations were tested to see how the projectors could move. One method involved placing a sheet of paper under each projector and using this to lift and move them during the performance; another involved the projectors being placed on four domestic turntables. We found that the turntables were not ideal without modification as they tended to catch in certain places and did not allow for full control of the projectors.39 They were, nonetheless, included in the equipment provided to the projectionist in Liverpool as an option.

2.3 The sculptural component

The sculptural component provided by the estate as an element of Ten Years Alive was the long string drone, which also included a tone bar slide and two hardwood bridges. This type of instrument was originally developed by Conrad in 1972.40 At least two such instruments were used in previous renditions of Ten Years Alive: the original, wooden instrument created by Conrad in 1972, which is now in the collection of the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis,41 and a portable version of the instrument, which Conrad was able to transport as carry-on flight luggage whenever he was travelling to play the piece in international venues. Tate was supplied with a new version of the instrument that had been put together by the Conrad Estate. This new instrument was tested by one of the long string instrument players, David Grubbs, prior to delivery.

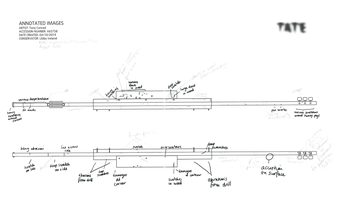

The time-based media conservation team worked together with the sculpture and installation art conservation team to condition check the contents of the package sent by the estate. The instrument was constructed from sections of softwood and rough-cut aluminum. To track any changes and evaluate how the condition of the instrument has evolved through activations, documentation was made showing annotated images detailing its condition (fig.8).

Fig.8

Sketch of the long string drone with annotations by conservator Libby Ireland

Condition report, Ten Years Alive artwork folder, Tate Conservation records

Given that this version of the long string drone is not a unique sculptural object made by Conrad himself, but one that was made based on the instrument concept he developed, the long string drone part of this artwork was considered a functional element of the performance.42 This means that the instrument can be remade if at any stage its condition would prevent the artwork from being performed again. The estate has provided us with instructions for how to remake the long string drone. Equally, Tate has been supplied with an instructional video made by David Grubbs on how to play and tune it.43

2.4 The performance beyond the documentation

A significant step in finalising the acquisition processing phase is guaranteeing that we have the necessary information to show the artwork in the future. This is particularly important in the case of performance art, as such documentation is what sustains the possibilities for the artwork to be materialised.

To ensure the long-term preservation of performance at Tate, we are applying our current Strategy for the Documentation and Conservation of Performance. As mentioned above, this focuses on capturing strategies, workflows, and tools such as the Material History, Performance Specification, Activation Report and Map of Interactions. All these documents are what we call working documents, which means they change as the artwork evolves over time.

Since the last revision of the dossier for transmission of Ten Years Alive, the performance specification has become the core element in the whole corpus of documentation. The performance specification helps us gather information relating to the performance in one document, while identifying what the material conditions are for the artwork to exist and helping us to determine whether we have gathered those conditions through the documentation in the artwork’s folder. In other words, reviewing an artwork’s performance specification allows us to reflect on the ‘condition’ of the information we hold, and if it is still enough to guarantee the artwork’s activation and transmission. In the case of Ten Years Alive, the performance specification forced us to ask:

- Is the information gathered enough to activate the artwork in the future?

- Is the information coherent? Does it reveal any contradictions? Are these contradictions part of Conrad’s way of transmitting this work?

- Is there any vital information missing? Who should we be in touch with to get further information?

Phase 3: Post-accessioning

The accessioning of a time-based media artwork is in part triggered by the time-based media conservation team, once they have checked and approved the condition of the work. This trigger takes the form of an email sent by this team to key stakeholders confirming that condition checking has been completed and that, from a conservation perspective, the artwork can proceed to be accessioned. However, other activities must be completed first, such as the acquisition coordination team making payment (when applicable) and the acquisition and long loan registrar team ensuring that the necessary documentation has been collated for permanent retention of the work. When all acquisition processing activities have been completed, the acquisition coordination team will instruct the acquisition and long loan registrar team that the artwork can be accessioned into Tate’s collection.

In the post-accessioning phase of the acquisition process, the time-based media conservation team must make sure that the work is displayable in the future. Among other things, this involves:

- Creating back-up files of all the audio-visual documentation supplied and created during activations and saving them in Tate’s digital repository.

- Labelling all the film elements of the work, winding the film reels with the right tension – a process we refer to as the ‘conservation wind’ – and placing them in cold storage under optimal environmental conditions.

- Finalising the performance specification and ‘teaching documentation’ and recording the ongoing reflection on and revision of these documents.

- Making sure all time-based media artwork components are carefully documented and trackable on TMS.

- Organising the digital artwork folder and creating a paper artwork folder by printing out a curated selection of the documents found in the digital artwork folder.

- Creating or updating the Artwork Conservation Summary document,44 outlining the work already completed and flagging any further steps to carry out in the future when the performance is requested for display or loan out.

At this point in the post-accessioning phase for Ten Years Alive we identified a few additional steps we thought would benefit the care of the work. For instance, we thought it would be useful at some point to explore further the possibility of making another long string drone while the one supplied by the estate is still playable. We also identified that, in the future, we will have to document the capacity and longevity of the long string instrument to operate, condition checking it before and after each activation of the performance. This activity should be completed together with an experienced musician who can flag any issues with the instrument. It would be helpful for us to attempt to determine the longevity and number of activations a long string drone would be functional for and at what point we might need a replacement.

Tate has now accessioned Ten Years Alive into the collection; to do this we had to expand both how we document and what we document in order to best accommodate this particularly complex performance. It is paramount for us to understand that the documentation will take us only so far in our ability to ensure the work persists into the future. The next section of this text focuses on the long-term management, preservation and conservation of all elements of Ten Years Alive including the film, sculptural and performance components.

3.1 Long-term management and conservation

This section will cover how the material history of Ten Years Alive is expected to change over time and how this will impact the long-term management and conservation of the artwork. We will focus specifically on three key moments of visibility in the artwork’s life: the acquisition of other artworks by the same artist, the display of the work inside and outside Tate, and the interactions with the artist and their collaborators. Although we will mostly address Ten Years Alive in this section, we will also make reference to other artworks and processes.

The material history of artworks has a direct influence on how those artworks continue to live, and even thrive, in the museum. This is especially relevant for performance works, whereby material expression may only come to fruition through their display. The conditions for their display are context- and site-adaptable, which enhances the complexity of dealing with the production of these works. A performance artwork cannot be repeated in an exact identical form; it will be different each time it is activated and therefore one should expect additions or omissions with each performance. These circumstances may necessitate a conversation with the artist to consider the evolution of the performance over time. At each activation it is critical to evaluate whether our categorisation of the work’s various elements is still effective and accurate. In other words, we need to evaluate the status of elements deemed constant and those deemed in flux, how the roles of these elements have changed, and in which ways this has affected the artwork’s identity or materiality. This strategy implies a process of perpetual construction and revision, with multiple moments of feedback generated by each activation of the artwork.

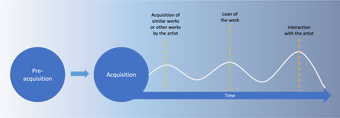

Fig.9

Diagram showing moments of visibility of a performance artwork during its life in the museum

Image: Hélia Marçal, April 2019

Indeed, alongside those that take place during the acquisition process, important interactions between collection care activities and the artwork occur mostly through the three moments of visibility mentioned above: the acquisition of similar artworks by the artist, the display of collection works both in and outside of the institution, and interactions with the artist or their collaborators (fig.9). These three processes require reflection on the performance artwork’s modes of operating, as they often bring new information to the fore or require the work to be reframed. For conservation, these processes also facilitate the assessment of the artwork in its active state – when the work creates new interactions, not only with people, but also with spaces, socio-economic contexts, material infrastructures and objects, among many others.

> Acquisition of similar artworks by the artist

The acquisition of similar works by the artist can bring new insights into the artist’s way of working, how they engage(d) with their artworks, and their ideas and expectations about their future. In the case of Conrad, who died before Ten Years Alive was accessioned, his playfulness was extensively highlighted by his previous collaborators in the interviews that we conducted when developing the method to document Ten Years Alive,45 which might have a direct impact on the way the conservation team approaches the care of the other works by the artist in the future. The many accounts of the importance of Conrad’s charisma and sense of humour ultimately led to the addition of a section in the dossier on Conrad and his personality. The acquisition of new artworks by Conrad in the future will benefit from the corpus of knowledge gathered in these last few years, while also bringing new insights into how we conserve Ten Years Alive.

> Display of the work inside and outside of Tate

The research that has accompanied the acquisition of Ten Years Alive has also allowed us to consider the practices associated with the lending of performance works. This has encouraged a critical reflection on both conservation and collection management procedures, and how our documentation practices could be adapted to better accommodate performance works. The opportunity to materialise the artwork in future within gallery spaces across Tate sites, of course, fosters a multiplicity that is important when understanding the material possibilities of the work and how they can be translated in various spaces and contexts, as well as for diverse audiences. But lending the work to another institution would allow us to explore:

- How our documentation is read outside the institution.

- How the artwork adapts when it is presented by the borrowing institution and the context it creates.

For the next display of Ten Years Alive it will be important to evaluate the effectiveness of the dossier, to expand on how the transmission between past and new performers occurs, as well as to understand the limits of our strategy and how we have to adapt it for the unfolding needs of the artwork. Conrad’s absence, which is now ever present in each activation, constricts our possibilities to expand the artwork and experiment with its inherent variability. Interacting with his estate and collaborators, however, does foster a sense of how he wanted the artwork to be performed and how different contexts affected his decision-making process. We are very privileged to have an expansive body of past activations that we can analyse, and an even more extensive pool of past performers with whom we can collaborate in understanding how Ten Years Alive is and can be activated.

As indicated earlier, collection management teams also play an essential role in capturing information concerning the activation of performance. The displays and loans out registrar teams each contribute to capturing the activation history of the artwork and aid in maintaining the range of detailed documentation that allows material changes to be observed and catalogued. The lending and display of the work outside of Tate’s established documentation infrastructure present noticeable challenges, as the documentation of the work is reliant on the borrowing institution. Therefore, when lending the work it is expressly important that its performance specification clearly states the documentation requirements for activating the work, which, in the case of performance, can often be much more expansive than those of conventional artworks. The loans out registrar team is key to ensuring that this information is both captured and delivered by the borrower, this being a necessary condition of Tate’s agreement to the loan.